Prologue: A Funeral

I’ve never seen the dogwoods so white,” he remarked, this pale man in dark raiment, the ferryman who would soon, before my people and others, lower Joe Billy to his well-earned Beyond. “Whitest I believe I’ve ever seen,” he repeated, nodding to a window that afforded a view of the courtyard outside. “The dogwoods. You remember? Those lily-white blossoms?”

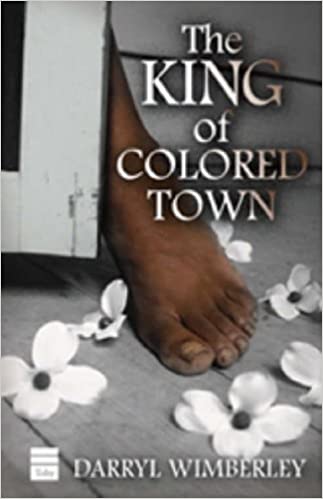

As if any absence from my home-place would be sufficient to disacquaint me with dogwood trees or their ermine display. Though in fact the dogwood tree’s blossom never really seemed to me to be white at all. I can remember springtimes sultry as only summers in northern Florida can be, when the blossoms of the dogwood trees seemed positively febrile. I can remember days when, seeing my big-toed feet shuffling from beneath the hem of my feedsack dress, I imagined that the blooms lining my sandy path were no more than blisters of pus, a yellow seeping.

A weeping wound, my grandmother used to tell me, could be salved with a liniment of dogwood leaves and it was not uncommon for the dogwood to be used medicinally, its bark boiled to counter a fever or ague, its blossoms burned or poulticed for a headache, or, especially during revivals, to cast out demons. My mother was the subject of one such exorcism. For her special affliction. There was no cure for Corrie Jean, but that did nothing to tremble the faith of her congregation. Count your blessings, people said. Move on.

Thus preserving the potency of their faith in the dogwood tree.

I was in Washington when I got the call about Joe Billy. A telegram, actually. It seemed so old-fashioned. I had been invited to the White House to perform for President and Mrs. Clinton and had arrived for rehearsal when, as they say, the word came. I went on with the concert, and remained for the short reception afterward. The President and First Lady were very gracious. He’s a real music lover, showed me his saxophone. I was driven back to my hotel in style along a boulevard brilliant with the blossoms of cherry trees.

It is hard to imagine a setting more glorious than our nation’s capitol in spring with the cherry trees in full display, but I have always been partial to dogwoods. And it seems to me now, looking out of this house of death to the dogwoods nestled beneath its gingerbread eaves, that my experiences are punctuated by the blossoms of Cornus florida. The sagging, worm-eaten building where I began my education, the only school in colored town, was wreathed in a grove of wild dogwoods. Miss Chandler would warm your behind if she saw you knocking the blossoms off those arbored limbs.

And the train station, where I first saw Joe Billy, was framed at its dock by a pair of dogwood trees, reaching each to each on slender, thwarted trunks to form a proscenium over the Pullman car from which Joe Billy made his theatric entrance, practically sailing from the car’s interior onto the loading dock, dropping his cardboard case to the pinewood deck. His leering guitar. Standing there like a millionaire. Barely seventeen. Hair pomaded back on the sides like Sammy Davis. Shirt opened two buttons down his chocolate chest. Wrangler jeans too new to be faded pulling tight over slender haunches. Quick and vibrant and short. His eyes, set close, bulged from their sockets in a constant state of astonishment or amusement or provocation, always eager to see everything, anything, that might offer a fight, a fuck, or diversion.

First place I made love was girdled by dogwood trees. And that other time. Where love had no part. They stretched me out between a pair of dogwoods. A full moon beamed through those blossoms. Whiter than any white you’ve ever seen.

“I see a stiss.” I nodded toward the coffin where Joe Billy’s youth and age lay arrested.

It was an aluminum coffin. Reminded me of the passenger coach that brought us Joe Billy, that car a much diminished version of the Pullmans originating in Chicago and locomoted all the way to the Sunshine State, stopping in Tallahassee for a change of line, and again at Perry, the final L.O.P. & G. feeder skirting the Gulf Coast on silver rails to pass tobacco fields and dairy farms and forests of hybrid pine before finally arriving at Laureate.

This was the town, the sultry place where Joe Billy’s youth had been sapped and where, his age spent, he was prepared for transport once again in a metal berth bright-shining as the sun. The coffin was lined in red. In satin. It looked like a coffee table for a whorehouse. Joe Billy would have laughed at that, had he been alive to see it. Had he been able to see.

“There’s a stiss thowing,” I formed the words once more on dry lips. I still have trouble, occasionally, shaping words. Doesn’t affect my playing anymore; a double-reed is more familiar to me by now than a lover’s kiss. But speaking I am apt, still, to lisp or mangle or mispronounce and so I am inclined, even now, even when I know I have elocuted perfectly, to blame myself for another’s misunderstanding.

“Through the eyelid. There. It thows,” I pointed, and the undertaker’s disgruntled cough told me I was onto something.

“Sorry, Miss Cilla. We couldn’t get it to stay closed.”

I laughed aloud.

“‘Couldn’t get it’?! The man’s dead, for God’s sake.”

“Well, yes, ma’am. Certainly. But that lid just would not stay down. And with the eyes—”

“I know about the eyes, Edward.”

He didn’t like that. It would have been all right if I’d addressed him as, say, ‘Mr. Ed’. Or certainly ‘Mr. Tunney’. But to call him ‘Edward’, just as if he was my employee, which at the moment he definitely was, did not sit well with the white man who had been settling colored people into the sandy loam of Lafayette County at outrageous prices for decades.

“How much for the coffin?” I asked.

“Twelve and a half.” He might have been pricing melons. “’Nother fifteen hundred for arrangements. Not including flowers.”

“Why don’t we just cut some dogwood?” I offered mildly. “Like you say. They’re awful white this year.”

White blossoms to frame a black man. I straightened abruptly from the casket. Even in mortis Joe Billy seemed to threaten mobility. A laugh. A curse. Nobody could predict what Joseph William King would do in life. Nor even, apparently, in death. But there were no eyes beneath those recalcitrant lids so badly tailored. The eyes had been gouged out not long after he had been put in prison. The fourth year? The fifth? To my shame I knew I could not precisely recall.

“Be something like fifteen thousand altogether,” Tunney continued his mercantile train of thought, all pretense at consolation dropped.

“It’s prepaid, Edward. We had a contract drawn.”

“That’s right. Thank you for reminding. So there’s a discount of—”

“Why don’t you just send a bill?” I suggested. “I guarantee I’ll beat whatever the County’s paying.”

He didn’t like that either. To be reminded how cheaply a man dead from prison could be interred. What the County would render in that circumstance. There would be no dogwood blossoms over those graves, or any other lily, you could bet. But here I was, come from out of town to pay top dollar for a nigger’s interment.

No sign of gratitude escaped Mr. Tunney’s well-masked countenance, only an unvarying smile stretching like a rictus. A plain of flesh caked with makeup, like a woman’s face. Or a corpse’s restored.

“Dogwood blossoms,” a chuckle burbled through that pan of dissemblance. “You sure can pull a leg, Miss Cilla.”

“No. Dogwood is what I’d like, I think.” I turned away abruptly. “A bunch of blossoms over the casket. And the gravesite, too.”

“Fine, then.”

“And do something about that stitch, Edward. It’s sloppy.”

A crimson tide threatened to destroy his pallor.

“Yes, ma’am,” was all he said.

I gathered my shawl over my well-wrought suit, passing through a cloying veil of velour to reach an uncurtained anteroom devoid of mourners. Through that chamber, down wide, limestone steps to a deserted, Sunday morning street and rented car. My feet appeared much larger to me than they should in their dark, Italian pumps. I pulled an ungloved hand roughly over my eyes. When I looked up I beheld a row of dogwood trees.

They formed a perfect line on the far side of the boulevard, a brace of symmetric limbs lightly garnered in moss, extending to display bowls of white blossoms that waved gently, like a bevy of beauty queens in a homecoming parade, carried to and fro in the train of a salty breeze. The car was near, now. I fumbled in my purse for the keys.

“Joe Billy, Joe Billy!!”

The words burst through tortured lips.

“I am so sorry.

--------------------------------

Comments

Winner of The Willie Morris Award for Southern Fiction, 2007

Publishers Weekly

Wimberley revisits the rural north Florida featured in A Tinker's Damn(2000) in this powerful portrayal of a segregated community at the height of the Civil Rights movement. In 1963 Cilla Handsom, a high school junior living in Laureate's "Colored Town," learns that her senior year will be spent at an integrated white school on the other end of town, where fear and racist fury permeate the halls. A brash charmer named Joe Billy King blows into town after robbing a church in Tallahassee and becomes Cilla's first lover. He discovers Cilla's gift for music and enlists the help of a teacher to secure Cilla access to music lessons and instruments. Cilla focuses on her music and her studies, but she and Joe Billy attract the attention of the Klan and are brutally assaulted. In the aftermath, Joe Billy sacrifices himself to protect Cilla. Though the tension lags after Cilla leaves Colored Town, Wimberley's take on the prickly themes of racism and poverty is made memorable by a gripping story line, authentic voice and dead-on dialogue.

(Apr.) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.

Kirkus Reviews

Fate deals two African-American teens different hands in Northern Florida's mean, segregated backcountry. Wimberley (Strawman's Hammock, 2001, etc.) paints complex characters against a backdrop of brutally violent racial oppression. In the early 1960s, the black section of Laureate, Fla., doesn't even have running water. Seventeen-year-old Cilla Handsom spends most of her time there taking care of her "simple" mother, who can nonetheless vividly play any melody she hears on the piano. Cilla has inherited her mother's gift, along with perfect pitch; she teaches herself to read and play music. No one notices until a cavalier, independent teenager named Joe Billy King moves to town. He and Cilla quickly become an item, and he informs the sole, educated, caring teacher at their black school about her unique talents. The town is on the verge of integrating its educational system, and the band director at the white school needs a French-horn player; he agrees to take on Cilla as a student if she will learn to play the instrument. School integration proceeds despite the objections of Laureate's white residents, largely thanks to Sheriff Collard Jackson, the one man not intimidated by wealthy bully Garner Hewitt and his two nasty sons, Cody and J.T. Cilla tentatively thrives in this new environment, and Joe Billy seizes an opportunity that will change both their lives. While stealing money from the collection tray at a church, he witnesses several men fleeing in Cody Hewitt's truck just before the church is burned to the ground. Sheriff Jackson gets Joe Billy off the hook in exchange for his testimony, but the incident sparks a racial war that ends in acts of horrendous violence against both JoeBilly and Cilla, who has just won a college scholarship to study music. When one of the pair kills a man in self-defense, they must decide together who will take the fall and who will rise above it. Truly heartfelt storytelling

Winner of The Willie Morris Award for Southern Fiction, 2007

Publishers Weekly

Wimberley revisits the rural north Florida featured in A Tinker's Damn(2000) in this powerful portrayal of a segregated community at the height of the Civil Rights movement. In 1963 Cilla Handsom, a high school junior living in Laureate's "Colored Town," learns that her senior year will be spent at an integrated white school on the other end of town, where fear and racist fury permeate the halls. A brash charmer named Joe Billy King blows into town after robbing a church in Tallahassee and becomes Cilla's first lover. He discovers Cilla's gift for music and enlists the help of a teacher to secure Cilla access to music lessons and instruments. Cilla focuses on her music and her studies, but she and Joe Billy attract the attention of the Klan and are brutally assaulted. In the aftermath, Joe Billy sacrifices himself to protect Cilla. Though the tension lags after Cilla leaves Colored Town, Wimberley's take on the prickly themes of racism and poverty is made memorable by a gripping story line, authentic voice and dead-on dialogue.

(Apr.) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.

Kirkus Reviews

Fate deals two African-American teens different hands in Northern Florida's mean, segregated backcountry. Wimberley (Strawman's Hammock, 2001, etc.) paints complex characters against a backdrop of brutally violent racial oppression. In the early 1960s, the black section of Laureate, Fla., doesn't even have running water. Seventeen-year-old Cilla Handsom spends most of her time there taking care of her "simple" mother, who can nonetheless vividly play any melody she hears on the piano. Cilla has inherited her mother's gift, along with perfect pitch; she teaches herself to read and play music. No one notices until a cavalier, independent teenager named Joe Billy King moves to town. He and Cilla quickly become an item, and he informs the sole, educated, caring teacher at their black school about her unique talents. The town is on the verge of integrating its educational system, and the band director at the white school needs a French-horn player; he agrees to take on Cilla as a student if she will learn to play the instrument. School integration proceeds despite the objections of Laureate's white residents, largely thanks to Sheriff Collard Jackson, the one man not intimidated by wealthy bully Garner Hewitt and his two nasty sons, Cody and J.T. Cilla tentatively thrives in this new environment, and Joe Billy seizes an opportunity that will change both their lives. While stealing money from the collection tray at a church, he witnesses several men fleeing in Cody Hewitt's truck just before the church is burned to the ground. Sheriff Jackson gets Joe Billy off the hook in exchange for his testimony, but the incident sparks a racial war that ends in acts of horrendous violence against both JoeBilly and Cilla, who has just won a college scholarship to study music. When one of the pair kills a man in self-defense, they must decide together who will take the fall and who will rise above it. Truly heartfelt storytelling