Chapter One

So pay attention now my children

And the old story I will tell

About the jungles and the freight trains

And a breed of men who fell.

Virginia Slim

Until the rails arrived virtually at their doorsteps, most people lived within a day’s walk of where they were born. America was smaller. Horizons meant something. The span of a life was measured out in strides.

A desire for more, a restlessness of the soul, always lay in wait.

It was a gnawing in the gut that comfort would abate for most, and conformity could subdue for others. Yet, in the hearts of some, the compulsion to wander was so irresistible that they had no choice but to follow. On horseback, on a raft, or on the last of their shoe leather, they would eventually leave everything they knew, seek solace in movement, and go in search of themselves.

These pilgrims, who longed for a different path, found that a river of steel had burst to life at their feet. Surging from the midst of the sprawling cities to the smallest hamlets, its tributaries traversed defiant mountain ranges, spanned impossibly vast prairies, and linked the remotest reaches of the country as they had never been linked before.

Hobos these pilgrims were called, phantoms of the road, and except to one another, they had no names.

The river of steel still flows through the land, but it is a changed land and a changed river. Its tributaries no longer reach into every corner, its currents are no longer inviting. The hobos that once were, are no more, having caught the westbound long ago. At the time of this tale, late in the last century, their golden age was a distant memory, their legacy known to but a dwindling few.

* * *

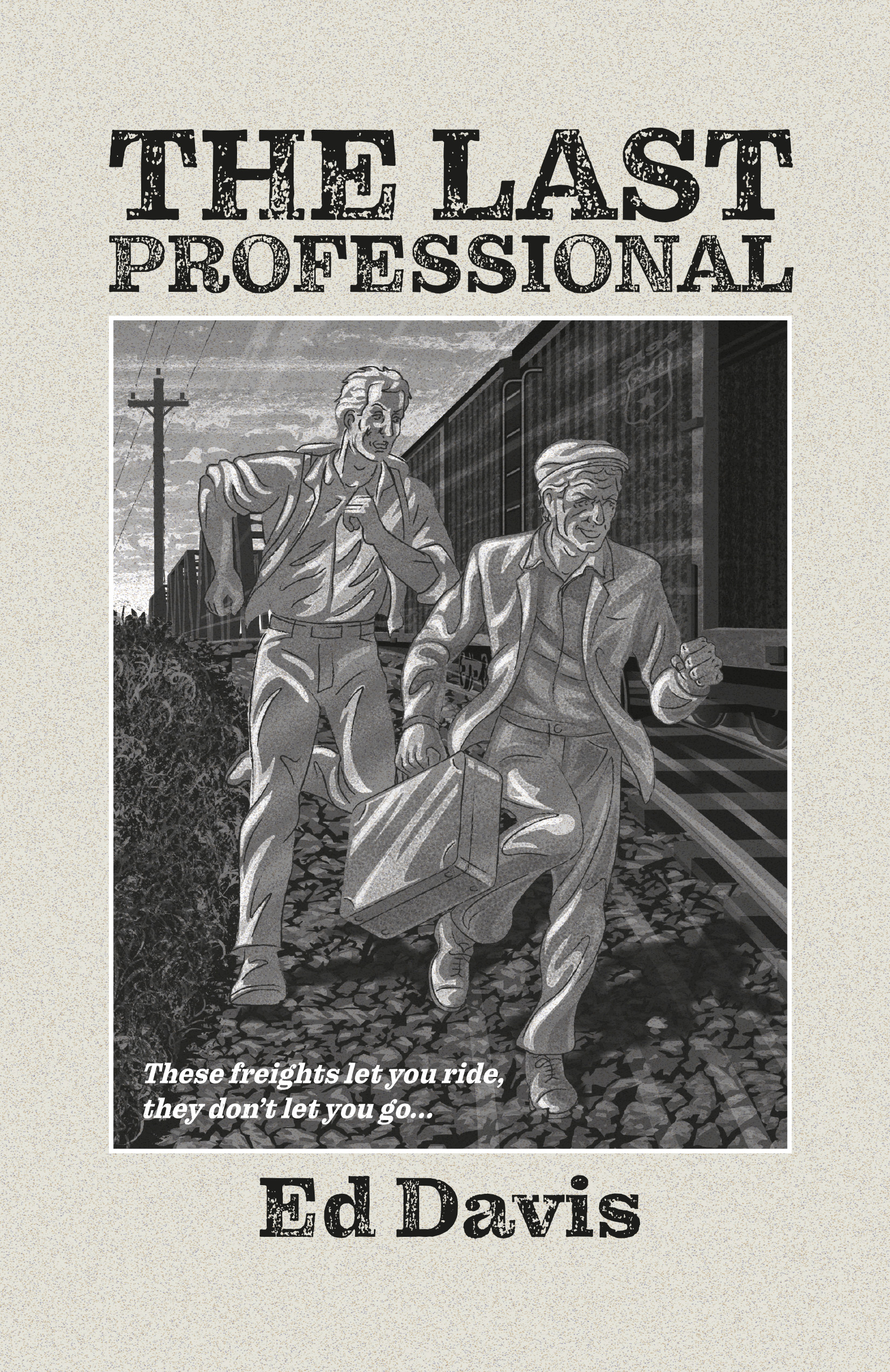

The country east of Roseville is a gentle plain of grassland and houses, tilting steadily upwards toward the Sierra Nevada. It’s a gradual climb that an automobile wouldn’t notice, but the eastbound freight labored at it, all six power units throwing thick black smoke into the afternoon sky.

In their boxcar Lynden and The Duke stood like sailors on a rolling deck—hands clasped at their backs, feet wide apart for balance, faces thrust forward into the wind. Their car was like an oven from a day’s worth of sun, so they pushed back both doors to catch a cooling breeze. On either side, the great brown landscape peeled by. Hills sloped into the long valley. Palisades defined the hollows of the grasslands. The open doors framed the passing scenery like a movie screen, a private showing just for them.

Lynden remembered his first time on a train—fifteen years earlier, when he was only eleven. It was summer and dry, and the hot metal side of the boxcar stung his hand. Inside, the car smelled of grain and warm wood.

He remembered the pasture behind his house in Auburn, Washington, and the railroad tracks just beyond the back fence-line—a line he knew he should never cross. He remembered the trains he often saw there. He’d learned to read the names on the cars, and he’d said their numbers aloud.

Occasionally the trains stopped. He’d see men riding in the cars. Sometimes he’d lean against that fence and talk to them. Sometimes he’d cross it. When the trains pulled away, the men would wave, and he’d shout back, his chest tight when they were gone. His father was gone. “He’s not dead. Just gone,” his mother would say, until he stopped asking. Lynden remembered them fighting, remembered hiding in the darkest corner of the chicken coop until it was over—until his mom would bring him in for the night.

When his dad left, the fighting ceased, and they were alone.

The train Lynden would never forget stopped behind his house the summer after sixth grade. Since then, everything around him had changed, everything but that train. Time had not faded it, nor improved it, nor altered it. The train was too strong. It went forward, always in his dreams forward, all the cars linked and bound, the great length tied and whole. The train was real. Its attraction was real. It had been calling him across all his days.

His favorite tramp was on it, one he had talked to many times. He’d told the man how much he missed his father. The man listened and seemed to understand. Then, on that day, as his train started to move, the tramp reached down from his boxcar and pulled Lynden in.

He could remember exactly what he felt at that instant: surprise, fear, excitement—hope. Maybe the tramp was taking him to find his father.

The tramp was just taking him.

From nowhere the smell of sweet tobacco came to Lynden’s nostrils. That scent, mingled with sweat, grime, saliva, was so primitive, so pungent it clung in his memory even now. The tramp rolled his own cigarettes—his fingers reeking of that pungent smell as they fondled him, probed him, held him if he tried to pull away. But he didn’t try, not really. For the three weeks they were together he did not resist.

He did not fight back.

For the fifteen years since, he’d been haunted by that fact. If he’d been drowning, he would have struggled for air, if slipping, he would have strained for any handhold that might arrest his fall.

But on that train, he drowned, he fell.

After three weeks of it, the tramp abandoned him—just like his dad.

He did not know the man’s name. “The Tramp” was how he thought of him, and he thought of him often—of punishing him for what he had done. What he hadn’t seriously considered, until a day ago, was doing something about it.

Only yesterday he’d been offered a promotion that would have made the business section of the Mercury News. “Data Dynamics, pegged as one of 1983’s fastest growing tech firms, today named Lynden Hoover, age twenty-six, head of Product Development. Hoover becomes one of the youngest Silicon Valley programmers to hold such a post, and possibly the highest paid.”

There was no possibly about it.

There was also no story.

Instead of saying yes, he’d said goodbye.

His coworkers, who did not know him well or understand him at all, were sure it was the added pressure. Either that or a ploy for more money. It wasn’t about money. Circuits were like barricades for Lynden, equations like battlements. When he brought them together with code, they created a fortress, a realm that was entirely his own—one he could control. He understood every inch of that world, just as prisoners know every inch of their cells.

As long as he was in self-imposed solitary, he could convince himself that he was fine.

But when Derek Zebel, the new VP and his immediate supervisor, cornered him in the men’s room—right after he’d offered him the promotion—it was like discovering he had a rapist for a cellmate. It pushed him over the edge. Not the breakdown edge or the bughouse edge. Just the quitting edge. He’d done it before. Hell, others at his level had done it before. All programmers were a little crazy up front, and all the good ones knew when to bail.

Yesterday was different. The new design was going smoothly, and the prototype of the DD 2000—Double Dildo the techies were calling it—was fifty percent locked down. But it wasn’t the Double Dildo that toggled him from a one to a zero.

It was Derek Zebel, and the confidence in his voice when he said, “I know you’ve been saving it for me.” The squeeze of his hand on Lynden’s crotch, not a caress but a vice-like squeeze, was a statement of control, and possession, and a declaration that he could and would do anything he wanted.

Anything at all.

And behind Zebel, fifteen years behind, it was The Tramp.

From nowhere the smell of sweet tobacco came to Lynden’s nostrils and he saw the glint of sunlight on polished brass. Zebel seemed amused when Lynden shoved him away, a reflex so strong that he could not have restrained himself. “Go ahead… play hard to get,” his new boss grinned, “but you’re not fooling anybody, and we both know it.” Lynden heard him, and though he didn’t know it, the question plagued him. And it wasn’t Derek Zebel’s voice that he heard, or Derek Zebel’s face that he saw.

It was The Tramp’s. The Tramp, standing over him. Not a face or a body or anything clear, but there was no mistaking it for anything, or anyone else.

And he felt, what? Dread? Shame? Longing? Maybe all of those. Or maybe just the hole they left behind.

Fifteen years, and he still wasn’t sure.

Small problems you walk away from, he thought. He’d been doing that most of his life. But from big ones, you run.

He sprinted through the plant, tossed his I.D. badge at the guard as he hit the door, and didn’t stop until he’d grabbed his backpacking gear from his apartment, hiked to the nearest onramp and stuck out his thumb.

It may have been an accident that the first ride he hitched ended in Roseville. He could accept that. But going down to the freight yards was a decision he’d been wrestling with for fifteen years. His Tramp might still be out there. Lynden pictured the man standing over him. After all this time he wasn’t sure he trusted the image, but the emotions it stirred remained clear and raw—always ready to ambush him when he least expected it, or when they would do the most harm.

The scent of sweet tobacco. The gleam of polished brass.

And in the background, all this time, that deep deadly rumble.

Beckoning. Fearsome.

The sound of the trains.

Now he was on a train again, the first he’d ridden since he was a boy. He’d jumped aboard as it was rolling out of the Roseville yard—an awkward and clumsy catch with the heavy pack strapped to his back. Somehow he got on, scrambling into what he thought was an empty boxcar. It was only when he was safely inside, catching his breath and shucking off his pack, that he realized he wasn’t alone. From the darkest corner of the car he saw a silver glint on a long steel blade, and the shadowy shape of the man holding it.

* * *

The Duke was not accustomed to being scared.

For two weeks now he’d been glancing over his shoulder, and every time his gut jumped a little. In fifty years on the road, bulls had pistol-whipped him, jungle buzzards had knifed him for the change in his pockets, and the killing wheels of the freights had always been there, ever sharpening themselves on the whetstone of the rails. He had seen men die beneath those wheels, seen them sucked in and ripped apart, but none of it had derailed him. Not until two weeks ago. Not until that mess in the jungle outside the Colton Yards.

Not until Short Arm.

Now he was running.

That night in Colton he snagged the first freight he saw—anything to get away. Turned out it was a Southern Pacific shuttle, so he rode it to the old LA yard, then ditched and lay low. He was sure nobody saw him, but on the Coast Express next morning he stayed hidden anyway.

Countless times that coastal had carried him from LA to Oakland. Usually, he stood in a boxcar door watching the ocean and the sand dunes and the broad blue sky. This trip he watched nothing, crouching in the car’s darkest corner, listening. He dreaded the moments when the train slowed down.

He made it through Santa Barbara and the crew change at San Luis Obispo. By Paso Robles his nerves were shot. What if somebody saw him when they set out cars at King City? What if the bull at Watsonville stripped the train? And if he made it to Oakland—what then? He was “The Duke,” and if some Sixth Street stew-bum recognized him, that was it.

Paso Robles might be safe, he thought, at least until things blew over. Only local freights stopped there anymore. In steam days there’d been a water tank at the south end and next to it a hobo jungle where some home-guard boys were still holding it down, their riding days long past.

When the coastal slowed for the grade south of town he left it. Twenty miles per hour, yet he hit the grit running and stayed up—not bad for an old man.

A week in the Paso jungle, and nothing. Part of another week and all he’d seen were rum-dumbs by the jungle fire and freight trains working up and down the grade. He started to relax, to tell himself that he’d never been afraid. He was Profesh, damn it. In a lifetime on the rails he’d faced every kind of danger the road could throw at him.

All without fear.

Then, one afternoon when he was coming back from the Sally, one of the home-guard boys slipped him word, one of the few who still knew the score. “Some yegg came through lookin for you. A Johnson if you ask me, though I ain’t seen one of those evil rat bastards since Hector was a pup. Big guy with a wing missin.”

That was three days ago.

He fled north. First on foot, then by thumb, but finally back to the freights. No place on the coast was safe for him now. That left the East, or maybe Canada, though Short Arm might still give chase. Most yeggs and jack rollers wouldn’t leave their home turf and worked a circuit where the law and the routes and the easy prey were all familiar.

But Short Arm was different, the last of his kind and crazy at that.

There was no predicting what he would do, only what he wouldn’t do.

He wouldn’t stop.

Since before dawn The Duke had been in Roseville, working not to be noticed. Though he hadn’t eaten in two days, he avoided the Salvation Army soup kitchen. The Sally was the first place Short Arm would look. Same with the last remaining hash house down on the main stem, and the watering hole next to it, both too well-known in their ever-shrinking universe to be safe. In any case, he told himself, he’d need what little money he had for the long trip ahead.

He snatched a couple of over-ripe pears from a neglected tree in an untended back yard, devoured them down to the seeds, and licked his fingers clean.

The next northbound left at four o’clock, the next eastbound not long after. The Duke had ridden both many times before. Unless he wanted Short Arm to catch him and kill him right here, he’d have to flee town, and flee the state, on one of them.

While he waited, he stayed clear of the yards and the rescue mission and the park where a few bums dozed in the shade. He changed his usual mackinaw and work pants for a dispatcher outfit. His slacks, old suit jacket and yellowing white shirt turned him into a retired railroad employee. He would think like a side-tracked dispatcher, act like one, go to all the places a retired railroad stiff might burn time. Since hitting town he’d spent a few hours in the library and a few more down at the mostly empty Roseville depot swapping lies with the custodian.

At half-past four—freights can always leave late, and often do, but never early—he ducked between some broken-down bad-order tankers parked on a dead-end siding and hit a string of boxcars just as the power units began to move, pulling slack out of the couplings, the sound coming to him like slow thunder from the head end of the train. He found an open boxcar and tossed his road-worn leather satchel into the darkness inside. He followed after it, with a grace and ease that belied how complicated the movement was, and suspended, for a moment, his terror that Short Arm might be waiting for him there.

* * *

“I’ve seen prettier catches,” the stranger stepped into the light.

Lynden flashed on the last time he’d been with a man in a boxcar. The fear, the excitement, the shame—all of it switched on in an instant. But there was no cunning in this voice, no threat. Only wariness.

“What do you figure that backpack of yours weighs?” The hobo was a compact old man, a foot shorter than Lynden and well north of sixty years old—the rugged features of a life lived outdoors imprinted deeply on his face. He wasn’t brandishing the knife, just making sure Lynden could see all of its twelve-inch length.

“Forty pounds, forty-five maybe.” In the hobo’s other hand Lynden saw a battered valise. “How about that bag of yours?”

“Ten pounds,” the hobo considered. “Hell, eight pounds. And there’s times I got nothin but my wits and my walkin stick. Seein all your gear, I don’t guess you’ll be wantin mine,” he opened his bag and placed the hunting knife inside. “This here’s my boxcar, but you’re welcome to share it, long as you behave.”

“I’ll do my best,” Lynden felt himself begin to relax, enough to offer a hint of a smile along with his answer. “Where’s this train heading, do you know?”

“Wherever the hell she takes us,” the old man stepped to the open door. “If she swings north up here, then it’s Dunsmuir and on to Oregon. If she holds straight east, then it’s over the hump to Reno and Sparks. You goin somewheres in particular?”

“No. Just like you said, wherever the hell she takes us.”

* * *

In the fifteen years since he’d been hauled into that first freight, everything in Lynden’s life had changed completely. Yet, out the door in front of him now, a familiar watery image of a shadow train shimmered dimly beside them. He remembered that from before, and it was just the same. Silver wheels honed and polished themselves on the anvil of the rails, the air filled with their raw, steel scent. He knew the smells—diesel and rust—and a roar like the ocean in a shell. His feet vibrated with the strain of a hundred thousand tons and the surging of the air lines and the flexing of the springs. Doors banged, metal slapped, dust flew. This was the train that threaded through his dreams, The Tramp’s train. It pulled him, relentless as gravity, but onward.

Their freight headed east at the switch, then climbed a ridge rising gradually above the valley floor. Lynden scanned the wide, sweeping land of ranchettes and open range that spanned to the south below. A row of palm trees undulated over the rolling hills. Not far from the tracks, billboards blared at the heedless freeway traffic speeding by. Horses grazed in dry pastures. On the larger estates, the unreal blue of swimming pools glittered like cold gems sewn into the fabric of the warm, brown plain. As the track curved, Lynden could see the full length of the train. This thing’s more than a mile long.

Fifteen years long.

Within an hour they were deep into the Sierra Nevada. Pines and huge cedars crowded close against the tracks; cars moved at a walker’s pace. The Duke stepped back from the doors. Lynden remained in the waning light, and watched the hard-edged landscape soften into pastels, evening’s gossamer veil layering mystery over the meadows, suggesting secrets in the forest glens.

Night, and still he watched. High in the mountains a harsh wind bit his face and eyes. The sudden cold and dark enlivened him. Moonlight illuminated the great rock faces rolling by, close enough to touch. Tunnels and snow sheds. Patches of snow like icing on the ground. They were crossing a trestle over a deep canyon. The snow in the bottom, a hundred feet below, glowed as if lit from within. He imagined himself stepping off the edge of the car and falling towards it—the thrilling release, the wind in his face and his hair, the gentle grasp as he sank in.

The last sheer face of Donner Summit rose, menacing and ghostly, before them. The rock’s cold white fingers reached into the obsidian sky. A snow shed opened, and one after another the cars were sucked in, like the mountain inhaling.

Magnifying the train’s roar, the snow shed grew darker, eclipsing light and shadow when it became a tunnel. Lynden clutched the edge of the door. He touched his palm to his nose. His eyes searched the car, at the noise from the opposite door, then to where The Duke hunkered down. Blackness. He inched his head outside toward the front of the train, a hot wind coursed roughly over his face—the smell of diesel and damp and mold. His eyes watered from the wind and blowing grit. Nothing to be seen.

He closed his eyes and rubbed them hard. He could see then, but no more than familiar swimming colors behind his eyelids.

Lynden floated, weightless, sailing through a shapeless void, unable to sense the train’s direction except when it lurched. As he had watched the foothills in the daylight, and the forests of the mountains at dusk, he settled back and watched the absolute darkness.

The train emerged beneath brilliant moonlight and stars that, after that darkness, were as shocking to his eyes as a million small suns.

“Tunnels been known to eat greenhorns like you,” The Duke was standing beside him, moon glow playing across his face. “Me and some boys rode through the Moffat tunnel with this young fella one summer and damned if we didn’t lose him. While we were inside, the fool got up to relieve himself—relieved himself right out the door.”

The train’s character shifted as it plunged down the eastern slope. After hours of plodding, pleasant and harmless, it was gathering speed, uncoiling into a rolling threat. Lynden’s feet picked up the tension as a thousand brake shoes engaged spinning steel. The air filled with the hot metallic smell of friction.

Soon the boxcar began pitching wildly from side to side, its wheels at odds with the rails.

“You scared kid?”

“Yes… aren’t you?”

“I was, when I was like you. Ask me again, you ain’t so green.”

The rapid waters of the Truckee River threw darts of silver light back at the sky, and a hot wind came whistling through the boxcar doors. They were flying down the mountain, rushing and swinging, hurtling toward the great flat desert below.

Whether it lasted minutes or hours Lynden wasn’t sure, but finally the train began to slow onto the flats, its frantic spell broken.

In the distance, like a beacon, the pulsing glare of Reno drew them steadily closer.

Track #1

On the Fly — To catch a moving freight.

Before we took a break to eat and tend the fire, you were talking about the truth, remember?

Was I?

You said it’s all that counts. Strip away the good and bad, and what’s left is the truth. Those were your exact words.

Good words. Seems a guy will say almost anything for a drink of whiskey and some hot chow.

Maybe, but I don’t think you’ll lie to me.

Won’t I?

When we began, it’s the way you said you wanted it.

I guess I did.

The truth, then. Let’s start with who you are.

I’m a hobo, a stiff who rides trains. That’s true enough. You might see me waving out a boxcar door when you’re stopped at a crossing, waiting… if you see the freight at all that is. Or cooking up in a camp by the tracks like this one here… a jungle we call it… cause it’s usually tucked away in the bushes and trees. Maybe even walking down the street next to you. I’m not the sort you always notice, but I’ve been around. Just a colorful character from the old days, like in the folk songs. Listen to the steel rails hummin’, that’s the hobo’s lullaby.

That sounds like who you think I want you to be… not who you are.

Then maybe you oughta get your ears checked.

The truth, remember.

Whose… yours or mine?

You think there is more than one kind of truth?

Don’t matter what I think. You want the painless truth, the awful truth, or the final truth? You want the preacher’s truth, the lawyer’s truth? Maybe the lover’s truth is what you’re looking for. There are as many kinds of truth as there are kinds of people. You can pick it off the rack like a suit of clothes.

We’re after the real truth, aren’t we?

That can be damn hard to find. Harder to face.

I’m willing if you are.

You may not like it.

Chapter Two

Seeing the raveled edge of life

In jails, on rolling freights

And learning rough and ready ways

From rough and ready mates.

Harry Kemp

Lynden stood between the open boxcar doors, his eyes shifting from the anxious faces on the sidewalks to the neon brilliance of Reno all around them. Back in the shadows, The Duke rode quietly and watched.

Casinos glittered on either side of the tracks. Crowds waited for the slow rolling freight to pass. Some gamblers, frustrated with the train’s interminable length, were so eager to try their luck at the next gaming palace that they grabbed a ladder and scrambled clumsily across the couplings—risking more than a few dollars.

“Yard’s starting,” the old man said softly.

“What?”

The Duke pointed outside. They were still in the midst of the casino district, but a siding had appeared next to them, and another next to it, like the branches of a candelabra springing from its stem. Glare from the first of the freight yards many blinding floodlights, perched atop their fifty-foot towers, filled the car, and Lynden slipped back into a corner.

The rhythmic dirge of the freight beat slower with every turn of the wheels. Lynden and The Duke watched the yard slip by. To their left a web of sidings splayed out, to their right a wide gravel area with trucks and sheds. They passed a string of power units idling on a spur. The yard office came into view, then the depot, and both slid back into the night.

“She’ll change crew here. When she rolls out again, we can snag her by the overpass down at the east end.”

“We have to get off?”

“There’s desert to cross tomorrow. How much water you carryin?”

“A full canteen.”

“Yeah, we have to get off.”

The tempo slowed till the rocking motion stopped. With a dull clanking it came to a stone silent halt. The quiet was so intense that neither man spoke.

A burst of air blasted from under the car.

“Christ!” Lynden froze.

“It’s only the air release.” The Duke grabbed his bag off the floor. “You comin?”

Lynden shouldered his pack and stepped into the open doorway.

“Don’t move.” The Duke stopped Lynden with a hand on his shoulder. Its strength startled him. A few sidings over a low white sedan was cruising left to right, tires stepping clumsily over the rutted access road.

“Did you tangle with a yard bull in Roseville today?”

“Tangle? No… a guy chased me out of the yard. Told me to stay out. When he was gone, I snuck back in.” Lynden had liked the thrill of it, of disobeying. “Why?”

The sedan came to a stop.

Nothing moved. Boxcars ceased banging in the yard, engines quit their droning.

The sedan inched forward again.

“Maybe he didn’t spot us.” Lynden’s eyes fixed on the car.

“Like hell.” The cruiser pulled out of sight. They heard it accelerate as it hit the city streets. “Get your I.D. yanked twice on the same line, you get thirty days… county.” The Duke was scanning the open yard. “Guards will shake you down for everything you’ve got, and you’ll end up with a boyfriend if you’re lucky… ten if you ain’t. With that backpack on, can you run?”

“Can you?”

They jumped down from the car and broke into a sprint.

Lynden could run—Bay to Breakers every year, and three miles before work most mornings. But with his pack he was no match for the old man.

A hundred yards and no sign of the bull. A hundred fifty and still no sign.

The Duke ran past the service road that marked the yard boundary.

Lynden stopped there, feet numb, shoulders raw. He shifted the pack to relieve pressure, then heard a sound. He looked back.

The white sedan was almost on him.

The Duke was gone, hidden in the bushes. Lynden dashed to the first opening he could find and dove in. It was a tunnel through the thicket, branches and brush all around. His pack snagged. He lurched, broke free, tumbled into a hollow of weeds and blackberry brambles.

“Where the hell you been?” The Duke, crouching beside him, had his knife drawn.

“Jesus Christ!”

“Save your prayin for later.”

“What’s that thing for?”

“Him.” The Duke answered. They heard the bull’s car pull to a stop in front of them.

“Look… it’s not worth it, even if we go to jail.”

“No?” the old man spat on the blade, polished it with the heel of his hand.

Through the bushes, just yards away, they could see the bull’s legs and hear the snap as his holster opened.

“You can’t use that thing on him!” Lynden, against the rising panic of what he thought was about to happen, tried to whisper, matching the old man’s volume.

“Watch me.”

Beams of yard-light glare filtered through the bushes—The Duke held his knife in one of them and flashed its blade toward the tracks. “I’ve never stuck this thing in nobody, but I’ve never had reason to. Right now, he’s wondering if it’s worth it. Chances are we’re leaving his town. Chances are he won’t ever see us after today. But he knows what he’ll see if he comes in here.” The Duke flashed the knife some more.

They watched the legs take a step forward.

“All right,” the Bull’s voice, loud but lacking conviction, made them both jump. “I know you’re in there.”

Lynden opened his mouth as if to answer.

The Duke stopped him with a hard look.

Stillness.

“Don’t let me catch you in my yard again!”

The legs took a step backward. The holster snapped.

Moments later the car pulled away.

* * *