Chapter 1

On April 22nd, 1986, a few days after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion, I, Jeremiah Ashley Simmons, found myself being squeezed from my mother’s womb and into the world.

This grand event took place in Fort McMurray, Alberta, in Northern Canada.

My mother, I would later learn, decided to name me Jeremiah from a narrowed-down list of biblical names but it had never quite caught on.

Not in my eyes, anyway.

In fact, most of the children I grew up with knew me not as Jeremiah. Rather, I was Jeremy Simmons, or simply ‘that fat weird kid who staples paper to his arms.’

The blood dripping from my stapler wounds came from an extensive bloodline of gamblers, religious fanatics, capitalists, and mental-disorder-ridden, chain-smoking hillbillies.

These genetics also meant my parents were destined to be blessed with five unique shit-storm magnets for Simmons children.

In order from oldest to youngest, we were Melenda, Jeff, Scarlet, Jeremiah, and Julie.

Mother, Maxine Francis Vardy, came from a tiny harbor community on Random Island in Newfoundland, a mostly cut-off place only accessible by boat from the mid-1800s to the 1950s.

Deer Harbour was simply a church, a cemetery, and a small scattering of houses along a government wharf overlooking the vast Atlantic Ocean.

As the eldest sibling, Mother was expected to raise her younger ones.

It was just how things went in those days.

So, you could say that her early life was hard and because of that, she grew up fast.

Incidentally, a nautical disaster had ended up accidentally paving tar on many of Random Island’s beaches, the thick sticky and noxious substance floating to the shores, washing up and nestling into the grooves of the beautiful sea-polished rocks. Wet and marbled, they sat like planets in the burnished tar. Brightly colored saltbox houses perched on the ocean’s edge made up the small communities otherwise, while withered white churches lay sprinkled here and there.

Serene ponds were nestled among the rocky hills, while pothole-ridden roads twisted and turned through the unconquerable forest. Newfoundland’s charm lay—just as it still does—in its unforgiving landscape balanced with humid forests full of moss and exotic-looking mushrooms.

Albert Simmonds, my father, was also born and raised on Random Island. Luckily, my parents were biologically different. I might have had hillbilly blood, but at least I escaped the destiny of being born inbred like some of my first cousins on my father’s side of the family. The gene pool needed to be much improved in these parts of Canada.

“There wasn’t too much choice to pick from for boyfriends,” Mom joked whenever people asked how she’d ever ended up marrying someone like Albert.

Albert’s family had been working on the Atlantic Ocean as fishermen for generations. Most of them had dark wavy hair, cold ice-blue eyes, and a rather large and complex beer belly.

My father was also proud to have a grade four education.

Eleven of the Simmons’ children stayed in the same harbor where they were born, but not Albert though. He left as soon as he could, whereas his other siblings lived out their whole lives just a few hundred feet from the dilapidated house in which they’d grown up.

My mother’s siblings also lingered on Random Island to compete for whatever limited resources it had to offer, and the name of their community, Hickman’s Harbour, suited them well because everyone living there was a goddamn hick.

There was a little bit of a problem when it came to me, however, as there was always doubt within my immediate family circle if I even had Simmons’ blood. Maybe because of this, I never had any sort of a family relationship with any of the Simmons family members, not even Albert.

That didn’t matter; my mother took good care of me as an infant anyway.

I was enjoying my new life as a fat and healthy baby boy in northern Canada, and my mother said I was a well-behaved baby. Well, I was in comparison to her last child, at least. So, she had to say that as there was no option but to compare me with the unruly siblings born earlier.

Scarlet was my elder sister—Scarlet with the piercing scream that caused many restless nights for Maxine. But when I came along two years later, in 1986, I was quiet, easily pacified and barely cried. This period, it turned out, would be the only peace I’d ever give my mother.

The bedroom I inherited was full of books, old toys, and comics that my older siblings had graciously passed down to me, not that they had any choice in the matter either since Mother was not intent on buying new of anything that we already possessed somewhere in the household.

My eldest sister, Melenda, had her perfect signature on each cover of every one of those books and comics, carefully claiming each one, her signature markings part of an intense rivalry between my brother Jeff and her. They didn’t get along growing up. And no wonder.

Mel particularly hated Jeff, and they were always at each other’s throats. My younger sister Julie and I would replicate the relationship within our sibling rivalry. Like my aunts and uncles who fought over the limited resources of Random Island, we equally fought over the limited resources of our mom’s attention. Being mean to Julie was the only regret I ever had.

During one of my early childhood solo adventures, I found some inserts from a porn magazine inside a dumpster behind Uncle Bill’s convenience store.

That discovery changed my life forever, and from that day on, I was a dumpster diver, my stash of porn becoming legendary among my peers. I would sell the water-damaged magazines or 1-800 sex chat advertisements to other boys while also coveting my own personal collection, in which, of course, I kept all the best magazines for myself. All this, I kept in a battered homemade trunk in the forest across the street from my house.

However, unbeknown to me at the time, something devastating was soon going to happen to it, something to destroy my carefully amassed collection, items I held so dear to me!

During the winter of 1994, the city clear-cut the forest area, and this was where I had carefully stashed my array of porn; they said they did it to make room for a snow dumping area.

Hmm, I’m sure they did, I thought. Some would have said it was because I went against the good Lord! The city elders were instructed to destroy the scourge before it could spread!

Well anyway, that was that then; my priceless collection had been lost, devastating me.

It seemed there was only one thing left to do; I’ll try and find a silver lining to this dirty cloud. There must be something positive in it. I just haven’t discovered it yet, that’s all.

Soon enough, however, one came. At least I never got caught with that stash by my mom!

That would have meant discipline within our religion. Of course, I had to have been born into one of the toughest religions, especially where things like ‘the sins of the flesh’ were concerned.

My family members were conservative Jehovah’s Witnesses, a doomsday cult based in Christianity. The ‘activities’ at the Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses ensured kids like me were routinely bored out of our skulls; try sitting in tight wool clothing perfectly still for hours.

It was utter torture for a kid like me. Itch, scratch, yawn. Repeat.

Religion stole my childhood.

What little money we had as a family, the organization asked for. No, demanded.

“Y’all be generous now, when the good Lord comes collectin’,” they’d say.

We should all be generous? But they keep robbing us blind, I thought.

But I would look up, stealing a sly glance at my mother, wondering what was going through her mind. And there was one time I caught her looking swiftly away, probably sensing my beady eyes on her and not wanting to meet my gaze because of the guilt.

The guilt of giving to that church every cent we possessed to our names sometimes.

In fact, on that day, she felt around in her long skirt’s big front pockets, then brought out a cheque book and a pen, writing the cheque out then and there, right in front of me.

She said, “Jeremiah, now you go up there and put this in the donation box.”

My eyes almost popped out of their sockets.

As I wandered forward to go to the place where everyone would walk to put down everything they owned, my gaze went to her scrawled writing on the slip of paper in my hand.

Wasn’t this the woman who told me we couldn’t afford new socks?

Wasn’t this the woman who said a loaf of bread twice a week was too much?

Wasn’t this the same one who…well, you get the gist. That cheque to the church was for $113! It broke my heart knowing that we needed that money way more than these greedy Jehovah’s Witness bastards ever did, and we would have put it to far better use too.

No wonder we had to struggle all the time; she was putting all our money into the savings pot of that greedy church and its fattened elders who’d have been rubbing their hands in glee.

So, when all the kids at school went on field trips, I couldn’t afford to go.

We barely had access to nutritious foods either. Sure, I was angry that my mom gave money to a cult over us. I would only forgive the religion after I realized with certainty that Jehovah wasn’t even real to begin with. My anger at Him was a complete waste of time because I might as well have held a grudge against Santa Claus.

Anyway, every few months, a three-day Jehovah’s Witness convention would occur, during which we had to sit silently all weekend while old white men brainwashed their gullible flock of goggle-eyed sheep. In case you didn’t realize this already, I was a black goat among those whitewashed sheep, perpetually making them uncomfortable with my science-based questions.

Arguing with old men that dinosaurs were real became my only interest as a Jehovah’s Witness. Their bones weren’t something planted by Satan to test our faith. I was on a mission to convince the elders of the congregation, but it was a hopeless exercise.

Once I realized that there was no hope of persuading ignorant Christians by underpinning everything with science, I stopped wasting my time on the religion and its gullible flock.

Then, I became a bored child once again.

My only entertainment during church was the sliver of Big Red chewing gum that had to be rationed carefully, using it for mental stimulation for each two-hour session.

When I wasn’t busy with my Jehovah’s Witness duties, I spent every free moment I had trying to acquire money to make up for the cash my mother was hemorrhaging with abandon. This toxic trait turned me into the local elementary school bully.

Learning gambling skills, it wasn’t hard to trick other kids out of their toys and allowances, managing to turn every common childhood game into a gambling situation.

I conducted my business under rigged circumstances and inside partnerships, leading to many angry parents having to try to negotiate back their child’s items from me.

Of course, I was largely able to get away with my mischief because Mom was hardly ever there, or if she was there, she was dog tired, too busy working multiple jobs to put food on the table because the money that ought to have been feeding us was instead stuffing full those ruthless church elders. I sure would’ve liked to see their dinner tables!

Ruthless, grasping swines.

And of course, Albert wasn’t putting anything into our family in any regard.

Such was life; besides our church’s frequent schedule, I would only be at the mercy of my endless imagination and perverse fetishes, bored rigid most of the time, and kicking back against the rules of all kinds. Nothing good ever came from following them, so why would a boy choose to? Around me, far too many adults were blind followers, and I wouldn’t become one.

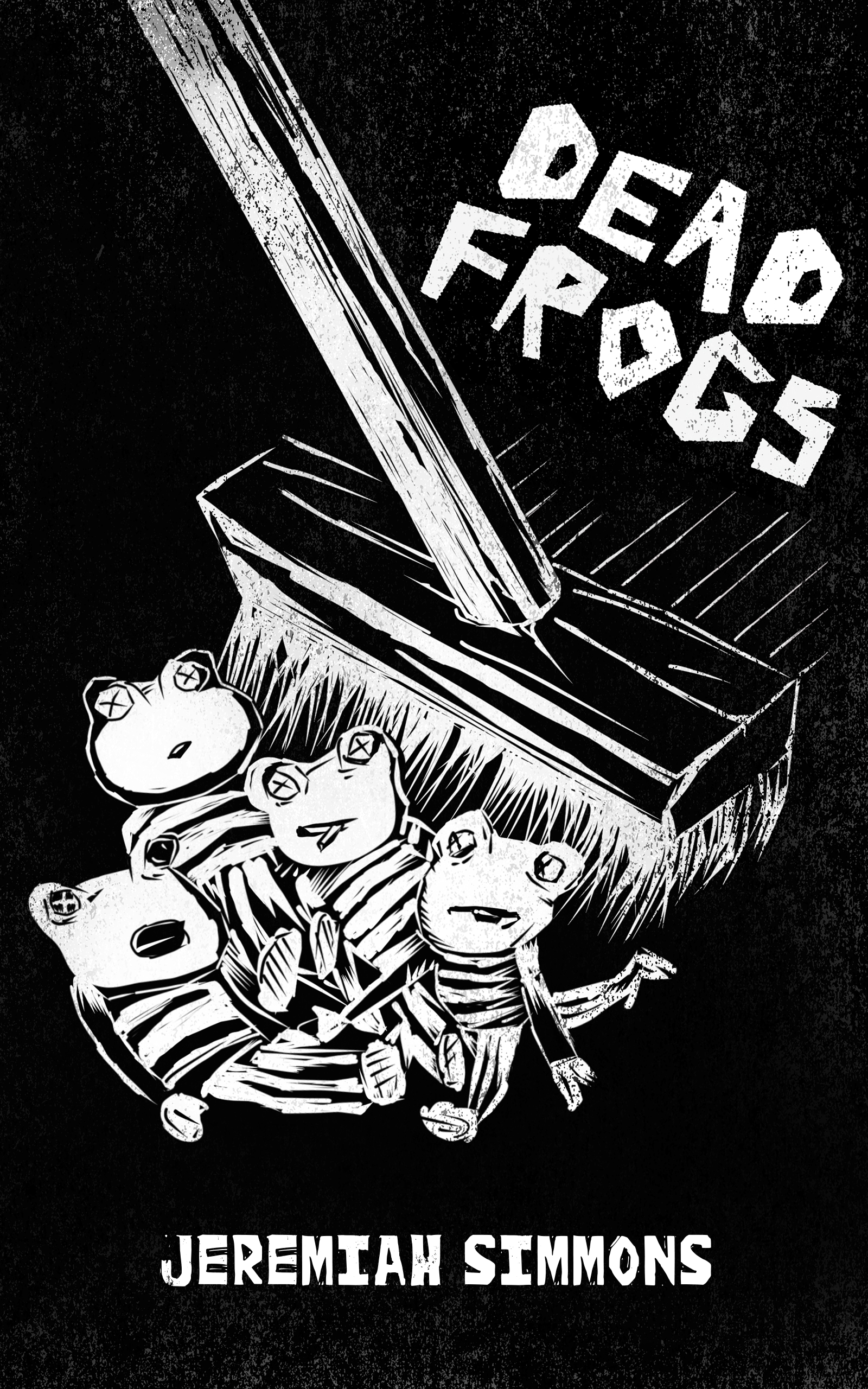

Mostly, if someone had asked me what it was that I most liked to do with my time, I would have answered that working with my hands was fun; well, that was when not living solely in my maladaptive daydreaming mind state. But my hands were skilled, and one time, they even created a plywood cage which I lined with plastic to make my own outdoor frog terrarium.

Don’t people say, ‘we learn by our mistakes’? And ‘pride comes before a fall’?

Both of those applied to me, because there I was, all puffed up at my own sense of achievement when one day, the frogs began climbing high again. This was a regular problem, that the frogs were surprisingly not so stupid. They somehow knew that unlike being in a glass-walled terrarium, they could utilize the friction of the plastic sides to scale the walls.

Slowly but surely, up they came, scaling the steep sides like experienced mountaineers until at last, two or three would pop up and wriggle out of the little air holes at the top.

They had a plan. It was to hop their way to froggy freedom.

“A little modification is in order,” I said aloud to myself, frustrated that yet again, those frogs were outsmarting me. “I’m going to stop those crawling and jumping little blighters from getting out and hopping off, never to be seen again. You just see if I don’t.”

And with that, I set about remedying the problem, devising some product developments.

But little did I know, this was going to be a guilt-inducing mistake.

A transparent plastic sheet had been lying around the yard and it seemed to be calling to me, use me, use me! Use me for the frogs! I am perfect for your frog problem!

And indeed, it was. Kind of.

It fit neatly over the terrarium, the perfect solution to prevent my froglets from their plans of becoming escapees. It looked good too, working like a treat.

The sun resumed beating down mercilessly soon afterwards, and little did I know that the plastic sheeting would instantly create a terrible greenhouse effect inside the terrarium.

There’s a very peculiar stink around here, I thought, sniffing about outside, wandering to and fro, seeking out the source of the sudden stench. Like something’s gone off. Or something is cooking. Something rancid. I sniffed, walked to and fro, sniffed again.

“It’s something around here. Hope it’s not upsetting my frogs.”

I went to look at the frogs, checking on them.

The gag reflex instantly set in upon realizing the sight and toxic smell before me were those of my frogs burning to a crisp, quite literally. On any other occasion, it might have been quite fascinating to see how a creature an inch thick could be reduced to an eighth of an inch by the sun. Some frogs, however, survived the heat dome and I was never able to be sure they were normal after that. Overcome by guilt and a terrible inner turmoil, I released them instantly back into the woods, removing all the dead ones. There was only one thing to do now.

Soon enough, I lined all the crispy brown critters up on the road, riding over them with my bike, squishing them to see what their anatomy consisted of. They were perhaps less dried out than I’d thought; the front tire immediately crushed them, some going off with a pop!

Their intestines and organs came shooting out at immense velocity across the dark asphalt, to both my simultaneous horror and macabre delight. This was one time of learning to face, accept, and dissect my mistakes, knowing countless more would be heading my way in life.

Yet again, I was intent on seeking out the positive in what was essentially a bad occurrence, telling myself that a person who makes the most mistakes will eventually have more successes.

After all, didn’t we read about it all the time? People who were bold, who went out on a limb to develop inventions and try new things, usually went further in life.

It was strange to enjoy the animals so much since it wasn’t at all how I’d been raised.

My mother was afraid of all creatures, and her number one rule was no pets, hence why the frogs had been destined to stay outdoors. Especially, she insisted, “No dogs and no cats!”

That rule proved tough to enforce. Some people have an inbuilt magnetism, an attraction that draws creatures of certain types from far and wide, and that was me.

Just as bluebottles and wasps seem to dart towards the ones who detest them the most, so too did every living creature want to become my new friend, probably sensing that although I liked them, they weren’t ever going to be welcome in our house. So, the frog ban—self-imposed—never could last for long despite setting the survivors free.

It seemed that everywhere I looked after that, there they were, a million desperate frogs, all waiting to move in like mini tenants hoping to finally be at the top of the social housing list.

Hundreds of small frogs received invitations to reside in my terrarium, but only after it received a program of refurbishment in line with new health and safety regulations of my own devising. In short, that means it was now safer to inhabit, the lethal plastic sheeting ditched.

Other ‘pets’ came to live with me too.

Buckets of water beetles were housed in the finest accommodation up in my tree fort, while I also nurtured large ice cream buckets full of tadpoles in various growth stages in the garage, and plastic aquariums of ants under the deck. My personal favorite collection was made up of the several jars of moths that I hid in my closet. These came with me to school so I could release them in class when nobody was looking. My prank worked best when the teacher would use the overhead projector, the moths flying straight toward the light, distracting the whole class and sending us all into disarray, filling the classroom with raucous laughter.

“Sir,” a boy would cry. “They’re coming out of your hair, sir. I think there’s a nest in there.”

“Boy! Don’t be ridiculous! Now, where are these wretched moths coming from?”

He batted at his own head, perhaps not sure if they really had hatched out of his unruly mop of hair. Admittedly, it did look like a nest. But nobody knew but me what the true source was.

Then there were the two-dollar feeder mice acquired from the pet store, to be housed under my bed; in time, not wanting them to grow fat and bored, it seemed a good idea to allow my mice to run free in public, letting them do what mice liked to do, especially in cartoons.

So, my favorite place to freak people out with my mice was on the bus.

“Aagh! It’s on the floor!”

“A mouse! It ran up there!”

“It was on my foot! Oh, ah, ooh! It’s gone up my goddamn pant leg! Get it out, get it out!”

And I would just sit there, my head swiveling, watching the mayhem and trying to suppress my giggles. People would get scared witless as if these things were man-eating lions let loose, leaping from their seats and doing a jig as if they were a troupe of Scottish country dancers.

The fun didn’t all come from pets though; some childhood adrenaline came from the thrill of being chased by strangers, a buzz like nothing else until I discovered hard drugs and alcohol in my teenage years. Ringing doorbells and running away was the height of fun in those days.

Once that didn’t cut it for me anymore, there was a need to move onto something else.

Adults annoyed me, especially the ones who bossed me about. One day, as I was kicking stones down the street, some guy came out of a house and eyed me.

“Boy, have you nothing better to do? I see you, always up to no good. Stay away from my car.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” I heard my voice saying before even getting a chance to think twice. “There’s only one problem, sir.”

“And what would that be?”

The man eyed me disapprovingly.

“I don’t know which one is your vehicle, mister.”

He pointed. A dark sedan, very nice too, new and pristine with its glossy iridescent paint.

No kid in their right mind would have wanted to play near a car like that in case they scratched it. “Righto, mister, now that I know, I can keep well away.”

Well, that was the trigger for what came next, that little incident. It’s just the way people say it is, that if someone expects the worst of you all the time, you might as well live up to it.

So, a new game was born, a new means of amusing myself by hurling rocks at expensive cars. It was great fun, seeing the bodywork crumple and learning where to give a hefty whack for the best sound effect, followed by the alarm going off.

Wheeee, wheeee! the sirens went.

Meep-meep, meep-meep…

For a bit of variety and spice, the pungent animal fetuses came next, the art of grabbing them by a leg or a wing or tail, flinging them with great gusto at passing vehicles.

The aim was to get a nice splat sound, relishing seeing a pink hairless tiny body sliding down the windshield or paintwork, leaving its slimy trail.

Most of these critters were still juicy, having been carefully preserved in formaldehyde.

These fetuses were ones I could readily get hold of, stealing them from a science storage room at school.

On a scorching summer day, the opened windows on the bus would also be in my crosshairs for an easy assassination target. One time, a huge rotten pumpkin somehow made its way through an open top window of a bus traveling at full speed, delighting me with its show of splattered goo.

The carnage of rancid orange gunge covered nearly every passenger as it exploded into the bus, then was sucked front to back by the air being sucked through as in a wind tunnel.

A young woman with big frizzy blonde hair suddenly turned vivid orange, horrified.

If someone driving had their window rolled down on a sweltering day, they were the next prey for my antics that never ceased developing; now, I’d sneak up beside their vehicle at the red lights and lean forward. “Whaaaa!” My scream scared them witless, my face pressed against their glass, eyes wide, seeing their faces turning white in horror and they’d leap sky high, almost bashing their heads on the roof of the car. One or two drivers lost control and jerked forward at the lights, ramming into the next car. By the time they’d pulled over to face the music from the driver of the car up ahead—the car that now had a damaged rear—I would have disappeared.

Giving heart attacks to strangers was an appealing thought; naturally, they’d try to catch me, but I would temporarily hide in some bushes or public washrooms until the coast was clear.

A lot of time was invested in causing trouble, just because of needing to stay away from my house as much as possible due to Mom being a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde type.

One side of her was a loving mother, the other a violent demon who terrified me in her demon form. But I was too afraid to escape the abusive situation like my three older siblings did with the help of child services. It would be possible to escape her wrath eventually, but not yet.

For now, Mother lashed out at us violently if we so much as stepped out of line, all growing to fear her. It was a good thing I rarely saw her then. The first time she subjected me to her violence was when she dragged Scarlet and me out of a fort we’d made for ourselves of the kitchen table, chairs, and bed sheets. Mom beat us with a belt and a wooden spoon that day, her anger palpable even before the hitting began. It seemed to us that this thrashing was for no reason at all, though in hindsight, we had dirtied and even tattered a few sheets she couldn’t have afforded to replace—unless, of course, she gave less to the church and fell out of favor.

So, she thrashed us with wooden spoons and bit us with her fake teeth until we were bruised and bloodied. Maxine would bite our fingers so hard that I honestly thought she would bite them off one by one, leaving bloody stumps. Incidents like this happened often whenever my mom was out of her mind, times when she’d turn into the monster, only to return as Dr. Jekyll, claiming no recollection of the violence she had committed against us.

No apologies ever came, of course, though we’d wait and hope for one someday. The thing was, if ever she did get around to saying sorry, it would mean she recognized this as abnormal.

If that ever happened, maybe she would be on the road to recovery.

It never did happen, never would.

If anything, she became worse, to a point where we feared being in our own home with her.

We learned it was mental illness driving her outbursts, and it was terrifying and confusing having a parent experiencing these frequent manic-depressive psychotic episodes. But we knew it couldn’t exactly have been fun for her either, pushing her to her limits with the stress of it all.

She worked in a newspaper factory, also delivering Avon products door-to-door, which combined meant she was now working full-time outside the house.

Ask any kids, and they’d say that in an ideal world, they wanted their mom home as much as possible. We did too, but that would have been if we’d had a real mother, one who did what mothers were supposed to. Ours didn’t, not now; we were barely scraping by from her income, and she showed us no affection or even interest nowadays.

She purchased the bare minimum—'bare’ being the operative word since the food was meager and the clothes always second hand. My family had to eat whatever food was available either on sale or expired, and in terms of clothing, everything I ever owned was secondhand or home-sewn attire. The word ‘unisex’ was frightening since I wore Scarlet’s hand-me-down girls’ clothes.

As for my father Albert, any notion of a relationship with him was a pipe dream. Maybe I never asked for one because it was always so patently obvious we were worlds apart, and driving to British Columbia together was the only time spent with him in my childhood.

Twenty hours straight we would sit silently together, eyes on the road ahead as if we were complete strangers on some enforced foray; really, we were off to pick up shipments of live crab.

Later, memorizing every inch of the dangerous British Columbian mountain pass would prove useful. In my twenties, I would find myself traveling the route again in the pursuit of a cargo more profitable than crabs, cargo that would give me a chance to thrive in this world.

Like my brother and father before me, I would come to drive these dangerous and yet simultaneously majestic highways for a living one day. But it’d be for a different kind of living.

On the way home from British Columbia, we stopped for gas and food. He bought some sort of a hoagie, quite a big one if I remember rightly and tore an end off it. He laid it on the center console as if feeding me was something magnanimous, even gesturing toward it with a great waft of his giant hand. “Eat up, son,” said Albert, eyeing me askance as if this was the first time he’d ever set eyes on me. The word son, whenever it escaped this man’s lips, was disingenuous; he spat it out as if it were a racial slur or another dirty insult. “You’re always eating shit,” he said.

“Yeah, well,” I answered. “Can’t say as I’m hungry, Father. So, I’ll pass.”

He would have immediately picked up the unpleasant sarcasm in my tone.

“Oh, so you’ll pass, will ya? You fucking waste of space. Think I want to be looking after you? Huh? Huh, do ya? Can’t even feed yourself these days?”

The next thing, a bunch of missiles was heading my way; Albert was throwing things at me, physically hitting me with anything within his grasp or anything not within his grasp, things he could reach by contorting and stretching himself. He reached. A tin mug came flying.

He reached again, backwards this time into the space behind his seat, soon sending a road atlas soaring over the seat and through the air toward me. He twisted around, looking in the side pocket. I froze and tensed up every muscle, accepting the beating as something rightfully mine.

It’ll be over soon… It’ll be over, I told myself silently. He’ll wear himself out. Don’t show weakness because if you do, then he’ll only get even worse.

So, I sat and stared at him, looking him right in the eyes to say, see, I’m not scared of you!

But really, I was scared, and he had me running from him; at least in my head, I was.

Then he smashed the dashboard of his truck with his fists and pelted me with full Gatorade bottles. After that incident, as far as I was concerned, he was a pruned branch on my family tree.

The beatings and mental abuse for me and my siblings were also frequent from Maxine too, so we learned the hard way to never complain about anything and abide by the laws of Jehovah.

“You know what’ll happen if you misbehave!” she’d holler, not caring who’d hear even if we were outside. “There’s plenty of foster homes that take kids like you. Though I have no idea why. But if they see sense and won’t take you, I’ll drive this car right off a bridge. Just see if I don’t.”

“Mom, please don’t do that…”

“I’ll leave you lot in the forest, I will, let you get eaten alive. Then let’s see how you feel about acting out… You don’t know how good you’ve got it.”

“Mom, please stop.”

“Just wait and see! I’ll burn the house down with everyone inside!” she’d scream.

One of Mom’s mental health rampages could strike anytime; there was no way to see it coming. She could flip into a crazy violent person, just at any moment’s notice.

By the time she was in her mid-thirties, the years of mental torment had taken their toll on her. She could have passed for a woman in her sixties, a long-lost member of the Addams Family. Even her own mother refused to look at pictures of her now.

These misdiagnosed mental illnesses would pit us against her for our entire childhoods.

That’s the thing about mental unwellness; that’s why the professionals call them ‘episodes’ because you can’t see when they’re heading toward you, not at all. One minute, she could be eating a sandwich or singing a sweet song while doing the laundry, and the next, her eyes were filled with fire and she’d hurl whatever she was holding, even a hot iron, and go on a rampage.

“What do you think you’re looking at, you horrible, disgusting child?” she’d scream. “You’re lucky you even have a home.” Another time, she cried, “I wish I’d never had you two!”

Comments

As direct as it is honest…

As direct as it is honest. The only way to write a memoir by telling like it is/was. Just one minor caveat: work on structure and add dialogue to relieve extended passages of description.