PROLOGUE

February 1817

A pale pink glow, the first light of day, suffuses the room. Thomas watches Susannah as she sleeps curled in a chair at his bedside. Her hair is still glorious despite the grey, her face still beautiful despite the lines, each line a record of their years together, their four children. He doesn’t want to wake her, but he needs to tell her something.

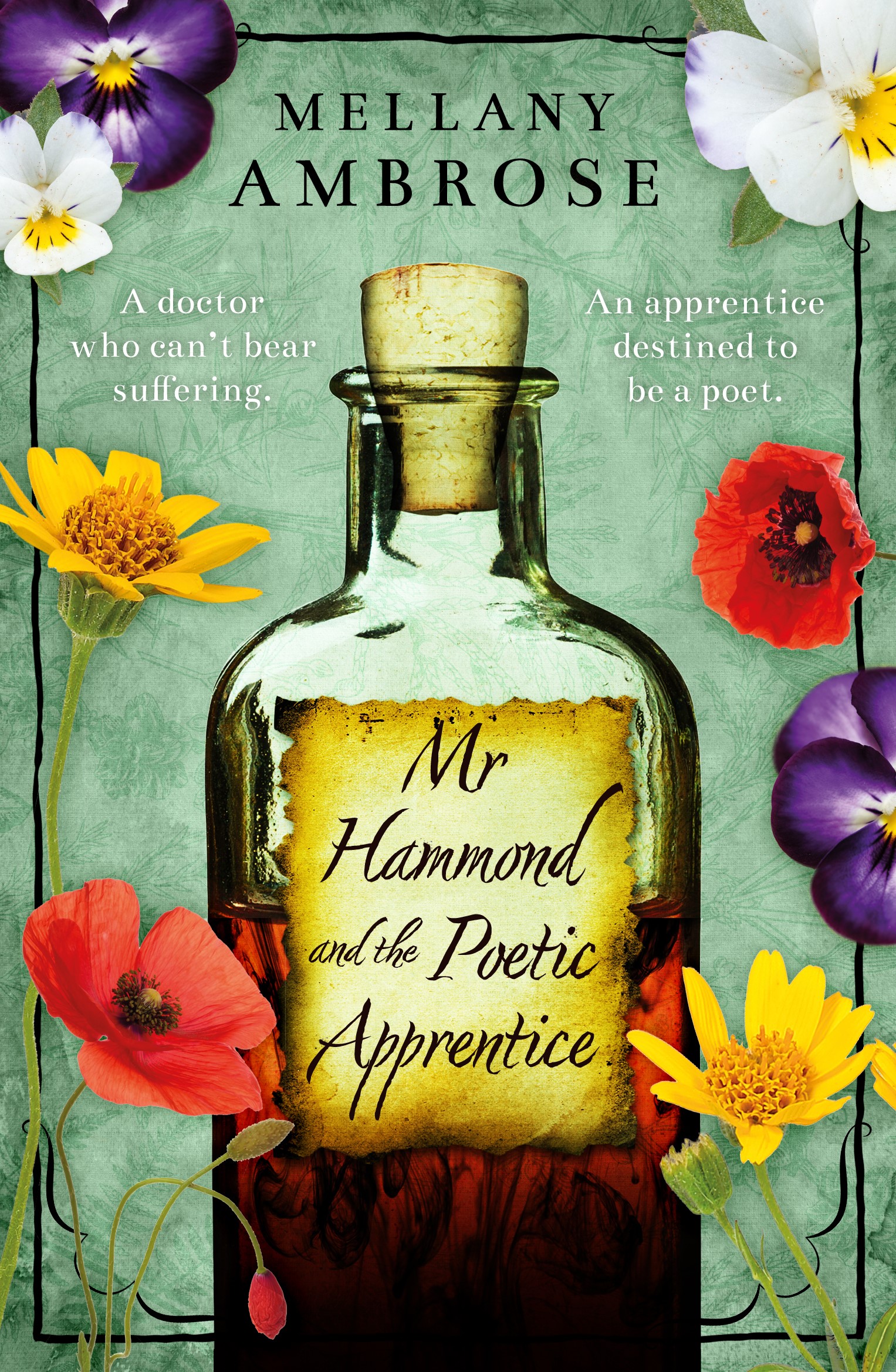

He reaches out and strokes her cheek. Her eyelashes flicker and her eyes open. Pain grips him and although he tries to hide it, she must see it in his face and picks up the laudanum bottle. He swallows the dose she offers, choking on its bitterness which even cinnamon fails to disguise. Laudanum, tincture of opium, beloved of the apothecary surgeon. Harvested from Papaver somniferum, the sleep-inducing poppy. In summer in his garden large papery petals crinkled in the wind, a flimsy flower holding a powerful hidden heart, the bluish-grey seed pod topped by its crown of thorns. An antidote to suffering.

The laudanum dulls his pain and his mind. There’s something he needs to remember, before he fades into oblivion. He struggles to form the words, his tongue thick and unwieldy.

Send for John.

Chapter One

July 1814

It had been a good morning. Mr Tuke’s leg ulcer was healing at last, baby Smith’s fever had settled and Mrs Brown’s cough had eased. Mr Reed had brought six freshly laid eggs and Mrs Wood a jar of honey. Thomas Hammond sent the last patient on his way and entered the dispensary with his son, Edward. Sunlight shone on the blue and white apothecary jars decorated with angels, peacocks, shells and flowers, highlighting the face of Apollo. The pleasing scents of aniseed and cinnamon made him imagine the exotic lands his medicines had come from. The steady pound of pestle on mortar echoed around the walls. Hardly changed since his father’s time, the room reminded him he was part of a grand medical tradition.

John stood at the scratched, wooden bench crushing herbs. His hair was a mass of reddish-gold curls, eyes blue, forehead high, mouth wide and the upper lip projected over the lower. His nose was sunburnt. The boy was forever running off to the orchard or the fields. An open book lay on the counter in front of the mortar. Thomas lifted the cover and read the title. Silence fell as John stopped mixing.

‘I don’t think you’ll find the recipe to cure Mrs Taylor’s gallstones in Virgil’s Aeneid,’ Thomas said.

‘I know it by heart,’ John replied. ‘I could mix it in my sleep.’ He bowed his head, clenched the pestle so the sinews in his wrist and hand stood taut, and scraped it so hard against the iron mortar it screeched.

‘No need to murder the herbs,’ Thomas said, trying to lighten the dark mood that hung between them.

Edward sat on a high stool, drew his horn snuffbox from his pocket and clicked it open and shut. Where John was fair Edward was dark, with large brown eyes and black hair curling over his collar. His mobile face with its ready smile could charm anyone when he chose. Sitting, he was as tall as John standing and his shoulders were broader. Hard to believe the boys were both eighteen.

‘I think that must be my hundredth tooth extraction,’ Edward said.

‘And a tricky one,’ Thomas replied. ‘You’ve surpassed the blacksmith, without fracturing any jaws.’ His son was talented, a quick learner with deft fingers.

‘It came away perfectly. The woman was extremely grateful.’

‘Edward,’ Thomas said, ‘I want you to make the pills today. I’m taking John on my visits.’

John stopped grinding the pestle against the bowl and looked up. ‘Me?’

‘But I always go on the visits. John’s only training to be an apothecary.’ Edward’s aggrieved tone might have swayed his mother, but not Thomas.

‘The Apothecaries Act changes all that,’ Thomas said.

‘I don’t see why.’

‘Because he must attend Guy’s. It will be the law. Six months for an apothecary and twelve for a surgeon.’

For Thomas the question was not why John should attend Guy’s Hospital but who he might meet there. He was bound to be taught by Astley Cooper. Even after the terrible mistake which had ended his career at Guy’s, Thomas still had some pride. He might not have shown the eye of an eagle, the hands of a lady and the heart of a lion Cooper said every surgeon needed, but he wanted to prove that he trained his apprentices well. Edward would be no problem. He’d been preparing him to attend Guy’s Hospital to be a surgeon for years. But John was another matter.

How was he going to teach this boy everything Edward knew? It would be an enormous challenge. To bleed with leeches and lancets, to pull teeth, set limbs, assist childbirth and diagnose fevers. And in one short year. He’d put John in the dispensary because his Latin was excellent, which helped with mixing, and it was more important for Edward to see patients.

Damn the Apothecaries Act. There had been talk of it for years but until now he’d never believed it would come to anything.

John held out the pestle to Edward, who snatched it from him and spun it in the air. Thomas’s heart lurched at the thought it might crash and be damaged, but his son caught it. John fetched Thomas’s medical bag and stood by the door. ‘Who are we visiting?’

‘Mrs Foster first.’ Thomas needed to see if the veronica and hyssop expectorant was working. Mrs Foster wasn’t improving as he’d hoped.

The village of Edmonton, with its dusty roads, few fine houses, rows of thatched cottages, two inns, church, workhouse, provincial shops and a charity school, was only ten miles from Guy’s in London but it could have been a hundred. It was separated from the metropolis by meadows and clumps of elms. To the east coaches travelled up and down the main London road, stopping at the Cross Keys Inn.

Church Street was hard and dry under Thomas’s boots, the sun beating down on the back of his neck. The medical bag hung from John’s hand, almost dragging in the dirt. John’s pale coat was shabby. Perhaps there was an old one of Edward’s at home which could be passed on.

John dropped behind and when Thomas turned around to find him, he was standing by a small pond.

‘Look!’ John pointed. Several dragonflies clung to the rushes, hovered or darted above the surface of the pond. ‘The colours. Azure and emerald. That iridescence! Such beauty.’

Thomas glanced at the insects. Years ago, when he was a boy, they would have excited him. He remembered playing in Salmon’s Brook catching minnows, the water cold on his feet; digging for earthworms in the herb garden, examining their segments; catching tadpoles and keeping them in a jar, watching them metamorphose into frogs which he held, feeling their moist skin expand against his hands. But he had grown up and had no time for those things anymore.

‘I wish I was a dragonfly,’ John said. ‘To possess that radiance and fly wherever I wished.’

‘You would have a very short life, and a useless one. All they do is procreate and die.’

‘But those few days would be filled with such delight, more than fifty common years could ever contain.’

‘I’d prefer fifty common years myself.’ Thomas started walking again. John caught up with him, but his eyes kept straying to the hedgerows. Thomas quickened his step. Apart from his anxieties about Mrs Foster there were several cases at the workhouse to see as well.

At the Fosters’ house the maid let them in. A boy poked his head from behind her skirts and cut through the air with a wooden sword.

‘Away with the infidels!’ he cried.

‘Master Fred, let Mr Hammond enter.’ The maid grabbed for the sword but missed.

John dodged sideways and raised an imaginary sword. ‘We will fight to the death to enter your castle,’ he said.

‘Stop!’ Thomas said, and the boys froze. ‘We’ve come to see your mother.’

John ruffled Fred’s hair. ‘Put down your sword for now. Even knights need a rest from rescuing damsels in distress.’

Mrs Foster lay on a chaise longue in the parlour, wearing a summer dress. She wore no cap and her reddish-gold hair was gathered at the back of her neck, but much had escaped and hung around her face in a wild fashion as if she’d been blown in a strong wind. Her cheeks were flushed. Thomas had attended her four confinements, treated Mr Foster’s lumbago and asthma, and the children’s illnesses. Last year three-year-old Isabella had died of croup despite his treatments and the taint of unspoken blame hung in the air like a miasma.

A pendant, depicting a blue urn and a willow tree, hung at Mrs Foster’s throat. The willow tree was made of Isabella’s blonde hair. A flash of Isabella, gasping for breath, came to him. He had ordered a warm bath before the fire, steamed the child and applied leeches to her throat. Her skin had turned dusky blue and her gaze had gone blank. He’d watched in disbelief, dreading Mrs Foster’s reaction, her grief. Now he reminded himself he’d done all he could.

‘Where’s Edward? He always cheers me up.’ Mrs Foster clutched a fresh white handkerchief in one hand.

‘This is my second apprentice, John Keats.’

‘Mrs Jennings’s grandson? A lovely woman, your grandmother.’ She lay back on several pillows.

‘How are you?’ Thomas asked. ‘Is the new expectorant helping?’

‘I’m feeling better, thank you, only spitting a little blood.’

Thomas touched the back of her warm hand and felt her fast pulse.

‘I’ll bleed you today.’

‘Are you comfortable?’ John asked. ‘Let me help you rest higher on the pillows.’ He put a hand behind her and lifted her up with surprising strength.

‘Stop fussing. Let’s get started,’ Thomas said.

John removed the engraved, silver lancet case and bleeding bowl from the bag.

Mrs Foster closed her eyes. She’d aged in the past few months, her full face growing thinner and exposing her bone structure, despite all Thomas’s medicines.

‘Hold the bowl, John.’ Thomas applied the tourniquet to her arm and patted her thin veins. They took time to swell. He grasped the mother-of-pearl handle of the lancet and cut. Blood dripped into the pewter bowl. ‘We’ll only take a cup today.’

The bowl wobbled in John’s hands and Thomas told him to be careful or else he would spill blood all over the Turkey rug. When the bowl was nearly full Thomas tied a bandage tightly around the cut.

‘You’re taking the medicines as directed?’ Thomas picked up the bottles by her side and studied their levels.

‘Yes.’

‘And sticking to the strengthening diet?’

‘I try, but my appetite is poor.’

She began coughing. Small, delicate coughs at first, as if clearing her throat, which gained in volume. Spasms wracked her body, her narrow shoulders. John helped her sit up and patted her back. She coughed and coughed into her handkerchief until she looked too exhausted to cough anymore. It stopped and she settled back on her pillows. Then she sat up abruptly, took a great inhalation and emitted a loud, whooping cough. A blot of red appeared in the handkerchief she held to her mouth, spreading outwards until it was soaked, flowing onto her hands and dripping onto her muslin dress.

Ruby-red blood. Arterial blood. A chill seized Thomas. His eyes were deceiving him.

‘Stop it, make it stop!’ she cried. Her eyes stared into his in sheer panic.

John took out his own handkerchief and wiped her hands, but it also became saturated.

‘John, go and tell the maid to bring some towels,’ Thomas said. ‘But don’t let the boy in.’ It would upset Fred to see his mother like this.

John left and Thomas was alone with Mrs Foster. ‘Try to keep calm,’ he said. ‘Panic will only make it worse.’

Mrs Foster held her bloody hands above her dress and hung her head, her hair falling around her face. He didn’t know what to say.

An arterial haemorrhage. Sometimes the treatments worked, but other times they only sent the illness into remission, until it roared forth with renewed might. The shadow would hang over the rest of the family; it was hereditary, so likely Fred and the other children would succumb. What was the cure for this dreadful disease, the great imitator, the thief of life? He had given her dozens of remedies already.

He couldn’t save her. Just as he’d been unable to save Isabella. He felt seized by a palsy, as if he’d eaten the shiny black berries of nightshade, Atropa Belladonna. Impotent. The worst thing for a man of action, a man who helped by bleeding, prescribing medicines, setting broken bones, assisting childbirth, even amputating limbs. With immense effort he pushed the feeling back down and shut it away.

John and the maid entered with water and towels. The maid washed Mrs Foster’s hands and John dabbed at her lips with a moist towel.

‘I will be well again, for my children, won’t I, Mr Hammond?’

‘Of course. There is much room for improvement. You must continue the treatments.’

He couldn’t tell her she might not survive the winter. It would only upset her more and her condition would deteriorate further.

He poured a dose of laudanum onto a medicine spoon and she swallowed it. He would study his books again tonight for mixtures to prevent further haemorrhages.

‘John will mix you some more cough syrup and deliver it later,’ Thomas said.

‘Thank you.’ Her eyes closed and Thomas knew she’d soon be asleep.

Thomas and John left the room quietly. In the hall Fred waited in a corner.

‘Can I see Mama?’ he asked.

He looked directly at Thomas. It disconcerted him.

‘Not now,’ Thomas said.

John knelt to his level. ‘She needs to sleep, Fred. But you can see her later today, I think.’

Fred bit his lip and looked as if he might cry. ‘You must go and fight some dragons with your sword,’ John said. ‘I see several in the garden.’

‘Do you?’ Fred picked up his sword and ran outside.

How quickly children forgot their troubles. John was good with the child, who on previous visits Thomas had found to be indulged and obviously needing more discipline.

Thomas and John walked in silence, back towards the workhouse. John’s light coat was stained by blood on the sleeves and front. Thomas always wore a black coat and black breeches, so blood wouldn’t show. His wife said he looked as though he was forever going to a funeral, and he’d once replied with gallows humour that often he was. She had winced and he’d regretted the remark.

A cart piled high with furniture passed them, the driver whipping the horse. John stopped at the pond and looked at the dragonflies again.

‘Sometimes patients cough up small amounts of venous blood, rust-coloured or like autumn leaves,’ Thomas said. ‘But that was arterial blood, bright red and full-flowing. Remember it.’

‘Her face, when she saw the blood…’ John said. ‘You must be able to do more for her.’

‘I’ve tried most of the remedies I know for consumption. Sometimes they don’t help.’ As John should know from his own mother’s case. The boy had insisted on administering her medicines himself and nursed her in his holidays from boarding school. He’d scurried about the room, overwrought and agitated, getting under Thomas’s feet.

John turned and looked at Thomas, his face contorted as if he’d suffered a physical agony. ‘Why be an apothecary if you can’t cure disease?’

‘I can ease their pain, make them more comfortable.’ Thomas forced himself to look John in the eye. His legs felt weak, probably from the heat. He didn’t want to admit it to John, but often even that was impossible and caused him grief. However hard he tried, however much good he did, there was always some pain he couldn’t relieve, some suffering that was too formidable for him to help.

‘It’s distressing to watch such suffering,’ John said.

‘One must be strong to help others, and not be affected by it.’

‘So you’re heartless?’

‘Not heartless. Becoming agitated by emotion won’t help the patient and interferes with the work.’

When Thomas was an apprentice, he’d been shocked by the things he’d seen. The first time he’d witnessed a compound fracture, the splintered bone sticking out of the skin, the man screaming, he’d wanted to run away. But his father had remained calm, dispassionate, practical and dealt with it. Thomas had learnt to imitate his father. He’d erected a wall to protect himself. And that had worked, until the tragedy of the boy at Guy’s had demolished the wall and he’d never been able to rebuild it.

‘How do you cope with the pain it causes you?’ John asked. Dragonflies flew around his head, shimmering and reflecting the light. John reached out as if to catch one, but it was too quick for him.

Why was this boy squandering precious time asking him this? They needed to go to the workhouse. Thomas’s patience snapped.

‘You work harder,’ Thomas said.