Chapter 1 – East Jerusalem

“I’m what’s called a seminarian. I’m working towards becoming a Jesuit priest.” Paolo spoke while he leaned against his apartment door, so badly chipped that another coat of paint was pointless. His neighbor faced him in the hallway, two meters away, hands on hips. A shock of dark hair covered the outer point of her left eye. Longer strands crossed her cheek before following the curve of her face and then disappearing under the brightly colored hi-jab draped across her head and left shoulder. The arrangement, Paolo realized, made it impossible to know the actual length of her hair.

He tried to recall if she had mentioned her name.

Her eyes were hazel, lips thin, and her general expression, entitled. Determined. As if on a mission to establish authority within the apartment building. Curiously, it was working. He felt as if he was blocking her way, even though the door that pressed against his back led into his apartment.

Paolo waited through the always awkward pause. He knew that neither age, gender, or anything else affected the mild astonishment that followed his answer to “… and what do you do?”

“You are becoming a Jesuit priest,” she repeated in a cadence that was half-question, half-statement, slowly forming each word on its own. Like Paolo’s, her English was accented, though it flowed more lyrically than his.

“Right,” he said, nodding. “It’s been about nine years so far, and it will most likely be another several before I take my final vows and actually become a priest. After that, I’m hoping for an overseas assignment. Perhaps America.” He half-smiled across the space while anticipating the next comment in the scripted sequence. Something politely meaningless, along the lines of “how interesting” or “well, good for you.”

“And that means ... what exactly?” she responded instead. “I mean, I know what a Jesuit is, more or less, and I know what a priest is supposed to be,” she said, her words gaining speed. “We’re drowning in them here. But saying ‘I’m going to be a Jesuit Priest’ doesn’t give me any information about what you actually do. I suppose it tells me something about what you believe in, but not a hint, really, about what you do with your days or what purpose you serve. It’s a bit like you telling me that you’re a vegetarian.”

The resting kindness in Paolo’s face evaporated as the damp coating of grime from carrying furniture and boxes, mostly books, up three flights of stairs into a sweltering, filthy apartment suddenly chaffed at his flesh. His head throbbed. A baby somewhere in the building wailed as three songs, each in a different language, collided around them, and the faint smell of diesel, which seemed to Paolo to be everywhere in East Jerusalem, was nauseating. His Duck-Duck-Goose Championship t-shirt, a remnant from his year as a high school exchange student in Minnesota, was soaked through.

Paolo briefly looked down at his sneakers and wiped the salt off his lips with the shoulder of his shirt before responding.

“Shirin,” he replied, her name suddenly appearing while he took an otherwise useless calming breath. “I am, in this exact moment, miserable,” he said slowly, as if speaking to a child. “So far, my misery includes a Ryanair flight that went to Bari instead of Florence with no explanation, a seven-hour bus ride, a missed connecting flight, lost baggage and a terrifying taxi ride to an apartment I foolishly rented sight unseen. The air conditioner is broken, there’s a dead cat in my bedroom, the refrigerator is buzzing so loudly I can’t think, and I’ve now learned that in the very first moment of meeting, I have a neighbor who prefers interrogation as a form of introduction instead of offering some help or a glass of water or, I don’t know … perhaps just saying hello. How do I spend my days? What purpose do I serve? My name is Paolo Venticinque from Pennabilli, a small town in Italy.”

He shook his head in weary disappointment. “You can look me up on Facebook if you want to learn more. Also, you should know, I am a vegetarian.”

Paolo took a single step into his apartment as a flutter of uncomfortable energy rolled through his chest. He tried to appear disinterested as he flicked at the door. Just enough, he hoped, for it to close completely. Scratching with both hands at the tingling on his chest through the damp t-shirt, he turned away just as the sound of the door’s latch connected to the frame and split the silence. His unsparing tone was already sprouting grains of guilt in his gut.

“What does it look like?” Paolo heard through the door as he took a step in the apartment’s short entryway. The baby’s muffled wails were still ringing in the background.

He stopped and tilted his head back. “What?” Paolo asked.

“The dead cat in your bedroom. What color is it?”

Chapter 2 – The Bishop

“Your Grace, I am pleased to introduce you to Paolo Venticinque, the seminarian we discussed,” said Father Dyson. “Paolo,” he continued with an open-handed gesture towards the robed man seated at the far end of the room, “the Most Reverend Excellency, Bishop Malatesta.”

Paolo nodded as he stepped into the conference room, uncertain how he might maneuver around the conference table and chairs to kneel and kiss the bishop’s ring. “Your Grace. It’s an honor to meet you,” he said with a slight bow from where he stood.

This was not Paolo’s first meeting with a bishop but was by far the most personal. Until this moment, he was either an adornment in a receiving line with an obligation to murmur, “Your Grace” within an allotted two-seconds or relegated with other teachers to the far corner of the room at the annual planning meeting of the Jesuit high school where he worked, and where he was now meeting Bishop Malatesta.

Seated at a table that nearly filled the room, Giuseppe Malatesta acknowledged the introduction by spinning his gaze in Paolo’s general direction. Tilting his head slightly, the bishop raised his eyebrows just above the coffee cup suspended at his lips. The cup lingered there. It moved neither toward nor away from his mouth, making the moment seem rehearsed to Paolo. Carefully orchestrated to establish status. An indication that this messenger of God was momentarily in spiritual or intellectual repose; not to be rushed. Paolo wondered if the pose had been plagiarized from someone higher up still in the curia. Malatesta’s full collar shirt and floor length cassock radiated ecclesiastical gravitas while the Rolex on his left wrist was a more subtle indication of stature. A black leather satchel, open and on the table, revealed a set of identical blue folders. One folder, with Paolo’s name written on the tab, was open, and apparently contained the recorded history of his Jesuit-tinged academic and spiritual achievements, attitudes, and deficiencies.

Malatesta appeared to be in his fifties, though his face was well-preserved and virtually without wrinkles. His bald skull, narrow eyes, ears pressed disturbingly close to the side of his head and rimless glasses produced a blandness that made the man difficult to describe. Bald, slight, Caucasian male is all one could confidently offer when forced to say something, perhaps noting after some reflection that he very slightly resembled a tortoise. The bishop’s only truly distinguishing characteristic, if one had the patience to look closely, were eyebrows plucked into unnaturally narrow strips that didn’t travel quite far enough across his brow. He was unremarkable at a glance and a bit disturbing when closely surveyed. Paolo detected the scent of cigarettes.

“I’ve been told you have a curious mind, that you’re quite well versed in theology and have a master’s degree in psychology.” He waved Paolo towards a chair. “Also, you’ve published several papers on the psychology of religious fanaticism. In fact, I read Aspects of Cult Behavior and Messianic Complexes on the train from Rome. Your work in that area is highly relevant to this assignment.”

Paolo, shocked the bishop knew details of his background, nonetheless sat without responding.

“As you know, there is a situation unfolding in Jerusalem,”the bishop continued. “After consulting with Cardinal Gianna, I have asked Father Dyson to relieve you of your teaching duties. You’ve been reassigned to Jerusalem to assist us there.”

“Cardinal Gianna?” Paolo repeated without hiding his surprise. It was one thing to speak privately with a bishop and quite another to learn that a cardinal, any cardinal, was complicit in determining his immediate future.

“These are the admission reports of the men currently residing at the mental health ward at the Shaul.” The bishop pushed all but one of the blue folders across the table. “Review the materials and depart for Jerusalem as soon as you can. Interview them and send your reports via email directly to me. Nobody else,” he said while placing his business card on top of the pile of folders. “The hospital is run by Dr. Doron Caldor. Jewish, but sympathetic to our situation. We’ve had several conversations, and he’s promised full cooperation. Plan on being there for several months. My secretary will help you secure accommodations and arrange travel. Just ring the number on my card.”

“Jerusalem?” Paolo repeated, not fully following the directives skipping towards him like smooth stones off a pond.

“One last thing. Until we are certain we have identified the culprit and have dealt with the situation appropriately, none of these men may be discharged from the ward without my direct approval. Caldor has agreed to honor that request. Understood? Questions?”

Paolo was utterly dumbfounded. Fifteen minutes prior, he was lecturing third-year high school students on Constantine’s role in the proclamation of the Edict of Milan in the year 313, which established religious tolerance for Christianity in the Roman empire. The tipping point for the role of Christianity on the world stage. Now he was apparently being relocated to Jerusalem after consultation between a bishop and a cardinal.

“I have quite a few questions, Your Grace,” he said more forcefully than intended. “Why am I being sent to interview patients in a Jerusalem mental health ward? Who are they? What am I looking for?” Paolo was confused and wildly curious. “I suppose a better question is, what are you looking for? What situation are you referring to?” he asked as the fog triggered by the Bishop’s directives began to clear, and what was being asked of him – demanded of him – became more tangible.

Malatesta looked sternly at Dyson. “Why is he asking me these questions? Did you not brief him?”

“No, Your Grace. My apologies. Brother Venticinque has been teaching all day. There wasn’t time to find a substitute to stand in for him, even for a brief conversation. We do have one coming tomorrow.”

“But I specifically ....” Malatesta started but then stopped, accepting the futility of continuing. He paused and stared at Dyson, the fingers of his left hand bent at the knuckles and crossing his lips as if to stop them from continuing on their own.

He turned his attention to Paolo. “You were to have been briefed.” His tone allowed for the possibility of being apologetic. He glanced at his Rolex. “The stories contained in these folders – hospital admission reports – are of men who believe themselves to be Our Lord, Jesus Christ, reborn here on earth. Come to save humanity from itself,” he said, as his hands waved in the air to reinforce the absurdity of the statement. “They are afflicted with a psychosis called The Jerusalem Syndrome. The top folder contains basic information about the Syndrome itself, including its history, symptoms, research, etc. It would be wise for you to also conduct your own research on the topic.”

Paolo sat quietly, processed the bishop’s explanation, and awaited additional information.

“I see,” he responded after he realized the bishop was waiting for him to say something. “That’s fascinating, and certainly connected to my work on religious fanaticism. Have these men been diagnosed as psychotics?”

“Some of them, yes. Others are simply tourists who became … caught up in the moment and fell into a type of transient delusion.”

“So then, what am I searching for?” Paolo asked. “The world is filled with afflicted people who make outrageous statements. They receive treatment; they recover or not. People understand them for what they are, and occasionally they provide a bit of scientific insight to help reveal some aspects of how the mind works. That can’t be what this is about. I have a degree in psychology, but I’m no clinician. So why does the Vatican care enough about a small group of disturbed men in a Jerusalem hospital to involve a cardinal, you and now, of all people, me?”

Malatesta looked again at Father Dyson, who stood leaning against the wall staring at the cuticles on his left hand. “Father, will you leave brother Venticinque and I in privacy?” he asked. “Please go about your day. My driver is waiting, and I’ll see myself out when we’re done here.”

“Of course.”

“And Father,” Malatesta continued, “I remind you that this entire discussion is confidential. You will share no aspect of it with anyone. No one at all.” He paused to allow his voice to reverberate before continuing. “When asked about Paolo’s departure, you will simply state that a unique opportunity opened up for him in Jerusalem and that I personally asked him to relocate. You have no other details. Is that clear?”

“I understand,” Dyson murmured as the door opened and softly closed.

Malatesta drained the last of his coffee, set the cup down and turned to sit fully facing Paolo. “You are correct. We have no interest in researching the underlying causes of this psychosis. In fact, you will discover that the syndrome has a history that goes back centuries. We’re mildly interested to know why its frequency has increased so dramatically over the past few years, but will leave that to the skilled psychiatrists, if such a thing exists, to sort out.”

“So, what’s the point of this … assignment?” Paolo asked again.

“Brand management.”

“Excuse me?”

“Brand. Management,” Malatesta repeated. “The analysis and planning of how a brand is perceived in the market. In this case, the brand is the Catholic Church. And the market is all of humanity.”

Paolo’s neck flushed in annoyance as he tried to brush off the bishop’s flippant response. He took a mindful breath before continuing.

“Your Grace, I mean no disrespect. But in the last few minutes, you completely altered the arc of my life. I arrived. You nodded, said a few words, handed me some folders and changed both my present and my future in ways I could not have imagined. My day began with at least the illusion of clarity, and now I’m utterly confused. I am eager to make sense of what you’ve said. I’m sure you can appreciate that,” Paolo said, not waiting for a reply. “So, I am asking you, respectfully, to be transparent about what you expect ... what you need, from this investigation.”

He paused before he continued. “I’m clearly missing important details about the situation in Jerusalem.” Paolo was concerned he had pushed the point too far and saw Malatesta’s hesitation before he responded.

“Tell me, Brother Venticinque, do you believe in the second coming of Christ? That Jesus will in fact return to establish the Kingdom of Heaven on earth? That he will, one day, come to battle the Antichrist and judge mankind?”

Paolo’s heart leaped to his throat. “So, this,” he thought, “is how my Jesuit journey ends. A simple question of faith any child would answer without hesitation.” His mind shifted to how he would explain his expulsion to his mother, who would defend him publicly while mourning his failure privately. He imagined the whispers of his disgrace on the corners of Pennabilli’s streets. Could Malatesta, he wondered, dismiss him instantly, in this room, or would a hearing or some other formality precede his expulsion? Perhaps they would simply assign a confessor to help him regain his spiritual center?

“Paolo, my son, you look like you’re going to fall from your chair,” the bishop chuckled. “This is not a test and there is no correct answer. Just thoughtful and thoughtless answers. I’ve no doubt your answer would be quite thoughtful. Reasoned and nuanced with balanced doses of faith, rationality, and theology. However, based on your pallor, I withdraw the question.”

The bishop’s unexpected humanity was deeply appreciated by Paolo. He remained silent as his heartbeat slowed.

“Did you know that a 2002 survey of 2000 active clergy from the Church of England showed that fully one-third of them doubt or disbelieve in the physical resurrection of Christ and that only half are convinced of the truth of the Virgin birth? Active clergy mind you. It’s unclear how many actually believe in the Second Coming, but I expect the numbers would be similar.”

“No. I did not.”

“Of course, they’re not Roman Catholics, but still, it gives one pause. What I find more astonishing is that so many continue to believe in the mystical aspects of the Church. Both among the clergy and among our followers. Including the Second Coming. And that, in fact, is at the core of the problem we have in Jerusalem.”

“What exactly is your position at the Vatican, Your Grace?” Paolo asked, the point of all of this still obscured.

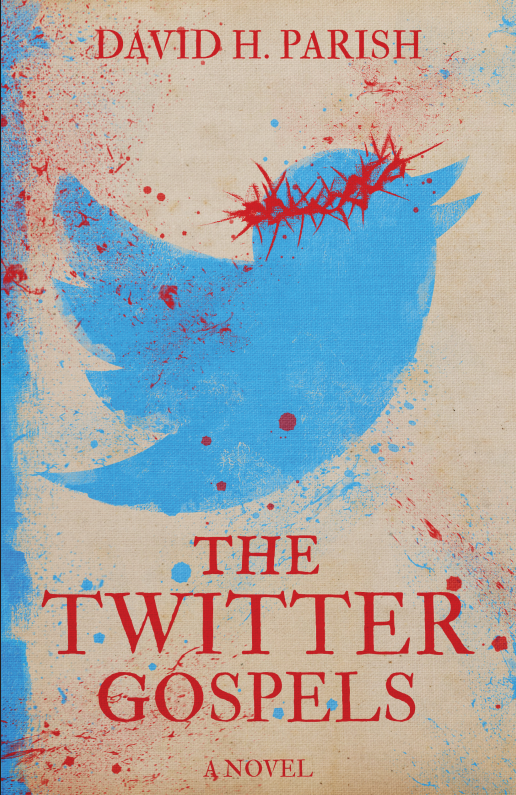

“I already told you,” he answered. “Think of me as a Chief Marketing Officer, assigned to the Vatican and responsible for branding the Catholic Church. And the problem I’m dealing with, the problem that brought us together, comes down to this.” Malatesta slid his phone across the table for Paolo to see. It displayed a message - a tweet framed by Twitter’s familiar blue bird icon.

Paolo leaned in to read the user’s handle, @ilvangelofinale, Italian meaning The Final Gospel, and then the tweet itself.

I come to you as Lord, Savior, Jesus Christ, risen to reveal false teachers. To renew compassion. To deliver salvation through brotherhood.

“He has attracted more than two and one-half million followers in less than two months,” Malatesta said while retrieving his phone. “His influence is growing quickly, yet he remains unknown to us and entirely outside of our sphere. Which is problematic.” He rose to leave. “We believe he is in Jerusalem. Most likely a patient at the Shaul,” the bishop said with a tone of finality. “You’re going to find him for us.”

Comments

Excellent premise. Trim the…

Excellent premise. Trim the dialogue a little to keep the reader fully engaged.