Auckland, New Zealand

Last Week

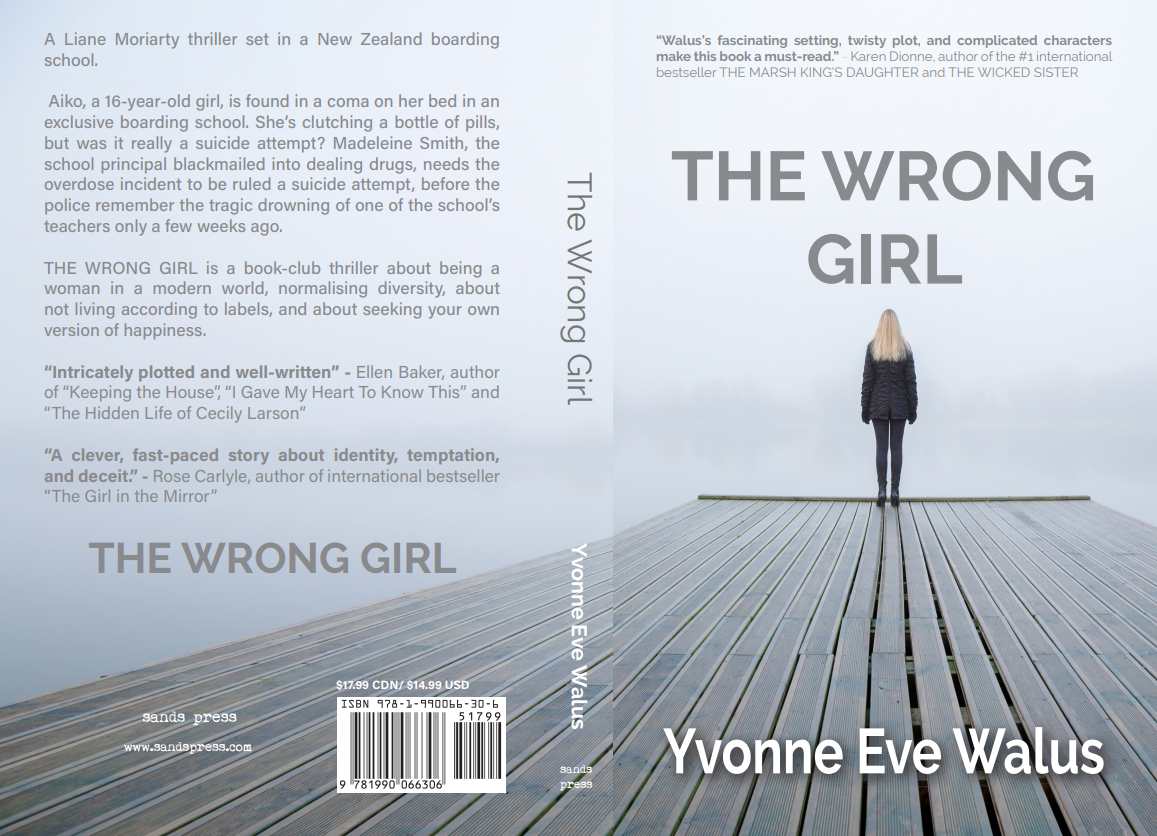

1: Last Friday morning: Madeleine Smith

Through the open door, the teenager looked asleep – eyes closed, face serene, black hair fanned out in threads of silk.

Madeleine Smith, headmistress of Arcadia High Boarding School, caught sight of the small medicine bottle tipped on its side. Three pink pills. Panic acrid in her mouth, she dashed into the room.

“Aiko? Aiko!”

No response.

The embryo-like curl of Aiko’s spine almost broke Madeleine’s composure. One of her students, a girl just like her own daughter, now just an empty shell.

A hollow buzz rang in her ears. She touched the limp arm, shook it. “Aiko!”

Nothing.

“Fire, ambulance or police?” said the voice in her phone. She must have dialled 111. The rectangle of the phone’s frame anchored into her hand. Firm. Familiar. Reassuring.

Police? No. A visit from the police was the last thing Madeleine needed. The school’s reputation was built on the premise of happiness – it wouldn’t survive another fatal accident.

As for Aiko – well, Aiko didn’t need the police, either.

“Fire, ambulance or police?”

Madeleine forced her brain to focus.

Wait.

Was it her imagination, or did the girl’s chest rise a few millimetres?

“Ambulance,” she said, her voice almost normal. “I think she’s still breathing.”

Yes. Ambulance. Definitely.

Aiko was alive. Everything would be all right. The school would continue to provide paradise on earth to girls whose parents could afford the luxury.

Except –

The room tilted.

What if they’d got the wrong girl?

2: Later that afternoon: Zero Zimmerman

Detective Constable Zara “Zero” Zimmerman of the Criminal Investigation Branch drove an unmarked white Holden. It was an old police issue vehicle, waiting to be replaced by a more climate-friendly electric Skoda, but it would have to do for her first solo mission.

The mission was a sucky one as missions went. The official objective, to investigate a near-death that would probably turn into a suicide attempt and a lot of paperwork. The undeclared objective: shut it down ASAP. But hey – the case would have to do, just like the old vehicle she had been assigned. Small steps. The New Zealand Police crawled into the twenty-first century two decades late, and the assignment of cases was less chauvinistic now, although Zero still suspected she’d landed the less-than-prestigious case strictly because of her gender.

A year ago, she would have been bubbling over with feminist indignation. Now she understood that – cliché as it might sound – every victim mattered.

“Aiko,” she said the name aloud in acknowledgement. “Aiko Hamasaki.”

On the face of it, Aiko Hamasaki had attempted suicide. But the cops from the Uniform Branch who’d inspected the scene earlier weren’t happy with the appearances.

“Seen a few of these before,” the constable had told her. “Far too many. But this one? Doesn’t sit right.” He wouldn’t elaborate.

“Hey Google,” Zero said. “Search for Arcadia High School”.

“Here’s what I found,” came the voice of Google Assistant, which – depending on Zero’s mood – sounded either metallic or melodious.

“Hey Google, let’s do some reading.”

Let’s do some reading was a Google Assistant routine that read out her paperwork, the news, and text-rich websites while she got on with driving, walking, or chopping vegetables. She assumed the first hit would be the school website. She was wrong.

“A young teacher drowned in a school swimming pool at Arcadia High Boarding School late last night,” Google Assistant read out.

“Wait, what?” Zero glanced in the rear-view mirror and tapped the indicator.

“Sorry, I didn’t get that.”

Zero brought the car to a stop in a patch of weeds that passed as the side of the rural road and grabbed the phone. The article was three weeks old. So no, the teacher hadn’t drowned the night before. Still, a drowning, and then a poisoning?

She looked at the phone. Arcadia School’s website was the third hit, wedged between articles about the hot summer taking its toll in drownings. There was also a memorial notice for Miss Parvati Patel of Arcadia High Boarding School, an article about the school’s netball team… and hang on, another memorial notice?

The second memorial notice was actually a funeral announcement for a student at St Alban’s Boys High. Dated the year before. The boy, name withheld for privacy reasons, had been seventeen years old. The cause of death wasn’t mentioned, but Lifeline’s number featured in the last paragraph.

“What the actual hell?” Zero whispered.

A suicide. Plus a drowning. Plus Aiko Hamasaki. Something didn’t add up. Or perhaps added up only too well.

She put away her phone and resumed her drive. The black metal of the gate that protected Arcadia High Boarding School from the outside world loomed in the distance when Zero’s phone chimed. She clicked the button on the steering wheel. “Constable Zimmerman. You’re on speaker phone.” A force of habit, the warning unnecessary when she was alone.

“Hi.”

One word. So much suppressed guilt. “Millie.”

The school gate grew bigger.

“You don’t have to sigh every time you say my name.”

Sisters, right? Can’t live with them, can’t slap them silly. Zero pulled over by the intercom pillar and waved her ID to the guard inside his booth. The gate slid to the side, and Zero motioned a thank you to the guard as she drove into a grove of densely green kauri trees. The she returned her attention to her sister. “Don’t be daft,” she said. “I’m glad you called.”

Millie snorted. “Sure. As glad as you were when I won the regional swimming gala.”

Zero felt pressure in her jaw. Forced her muscles to relax. “How can I help you, Millie?”

Another snort.

“Is it about the electronically monitored bail? It’s not fair that you’re not in home detention.”

Millie had been remanded in custody awaiting her trial, but the court date kept being pushed out in the wrong direction, the weeks morphing into long months.

“Millie? Would you like me to help you apply?”

“I wouldn’t ask you if you were the last person on earth.”

Ouch.

She needed to talk to Millie. Tell her that Dad seemed to have aged in the last few months, how fragile and sad he looked. But that barb had landed. “Look, I have to go.” Zero almost said I’ll call you back. That wasn’t how it worked, though. “Bye, Sis.” She clicked off.

It was official: Zara “Zero” Zimmerman – a red-haired orphan adopted first by a family of Gypsies in Romania and subsequently by a quiet New Zealand couple – now worst sister in the world. That’s why she had always been the second-favourite child. Always. Even before she’d landed Millie in prison. Before she’d spear-headed her sister’s arrest.

Their dad never said anything, yet he probably felt the wrong girl had been jailed.

She shook off the thought. A teenage girl had almost died today, and it was Zero’s responsibility to find out why.

February in Auckland usually felt like a sauna, and this year was no exception. As soon as Zero climbed out of the air-conditioned car her skin slicked with sweat. The school path curved upwards towards the admin building and back down to the gate. A loop, convenient for vehicles, oddly fitting to the image of a very expensive and very exclusive boarding school.

A pair of glass doors whooshed apart as a woman walked through to greet her. “Madeleine Smith. Headmistress of Arcadia High Boarding School.”

The voice was soothing, like an early morning by a lake. And yet something about Madeleine Smith made Zero’s cop senses burn bright red. The unnaturally straight spine? The way her eyelids curtained off all emotions? Or that she hardly looked like a school principal with cheek dimples and a blouse that sparkled like the ocean on a sunny day? Nothing schoolmarm-ish about Madeleine Smith. Charming – yes. Trustworthy – maybe. Full of secrets – for sure.

“Zero Zimmerman, Detective Constable, New Zealand Police.”

The handshake was firm and reassuring. If Zero had children, which she desperately and actively did not want, that handshake would have made her send them to a school administered by Madeleine Smith. If she had money, she’d invest it in whatever venture Madeleine Smith was running. If-

Zero Zimmerman, Detective Constable, New Zealand Police – gushing like a schoolgirl with a crush.

“Have you heard from the hospital?” the headmistress asked. Her left thumb worried the gold band on the ring finger. “They keep telling me Aiko is stable. But I don’t understand what that means.”

Zero did understand. The hospital had been her first stop. Aiko had ingested an overdose of sleeping pills and was in a coma. Flumazenil had been administered to counteract the benzodiazepine in the prescription medicine. When that didn’t have the desired effect, she’d had her stomach pumped. She was alive, unconscious, not convulsing and not responsive to external stimuli. Basically, not in any immediate danger; with the medium-to-long-term prognosis uncertain. The doctors had dissuaded Zero from interviewing Aiko’s mother.

“Stable. Means her condition is not deteriorating,” Zero said, aiming for gentle vagueness.

The headmistress plaited her fingers, released them, fidgeted with the wedding ring again. “Will she be all right?”

Zero side-stepped the question. “What can you tell me about Aiko, Mrs Smith?”

“Oh, please call me Madeleine, Constable. Mrs Smith is my mother-in-law.”

Was there a flicker of a sneer above the upper lip?

“Madeleine. About Aiko-”

“I found the poor girl passed out on her bed and called the ambulance. Really can’t say why they referred the matter to you. A couple of uniformed policemen were here earlier, and I told them everything I could think of.”

“Hopefully we can settle the paperwork quickly. I wouldn’t want to waste any more of your time-”

Why was Madeleine Smith being defensive?

“Now perhaps you’d be kind enough to tell me.”

“Is this really necessary, Constable? It’s obvious what happened.”

“It is?”

“Teenagers will be teenagers. You see it all the time with this me-me-me generation. Self-harming like cutting or purging or swallowing paracetamol – all of it attention-seeking. We’re doing our best as a school to build up their confidence and a sense of selflessness, but sometimes…”

No, not defensive. Protective.

A sound cut through the air off to the side. “Baaah!”

Zero looked. A charcoal-coloured sheep emerged from the treeline, crossed the driveway, and headed for the soccer field.

“Our lovely sheep mow the lawns for us,” the headmistress said. “The noise of a machine cutter would be out of alignment with the school’s philosophy.”

On her way over Zero had asked Google Assistant to read out the website of the “sought-after private boarding school for teenage girls”. Its motto was “Through success to serenity”, and the school prospectus brimmed with words like “well-being”, “holistic development” and “emotional maturity”. The main selling point, however, was total immersion in non-digital learning. There had also been a lot about sustainability and the environment.

Zero raised the single-use coffee cup to her lips, thinking that disposable containers were probably not aligned with the school’s philosophy, either. Fair’s fair, the taste of Styrofoam did nothing to improve the coffee. “About Aiko?” she prompted.

“Let’s get out of this heat, shall we? I’ll tell you everything you need to know for your report, then you can be on your way.”

And… dismissed.

As she followed Madeleine inside, Zero glimpsed a stretch of blue ocean at the bottom of the soccer field. The air smelled of oysters and freshly watered plants. She could hear a seagull calling in the distance and the occasional bleat from a flock of sheep. There were at least ten, maybe a dozen, and they were all black.

Impossible to imagine anything bad happening in this slice of heaven. Yet Zero didn’t need to imagine. It had already happened before. Twice, if you count the incident at the sister school. In view of Aiko’s overdose Zero would have to review both cases.

Before Madeleine could open the door to her private office Zero sank into one of the plush chairs in the reception area. She liked interviewing people outside of their comfort zone.

“What can you tell me about Aiko?” Answers to straightforward questions would establish a baseline of Madeleine’s gestures and word patterns. Anything out of alignment later would be a red flag. The headmistress wasn’t a suspect, yet Zero couldn’t shake the feeling she was hiding something.

“She’s a good girl,” Madeleine said in a tone that discouraged anybody to challenge the fact. “Above-average grades, pleasant manner, takes part in extracurricular activities, has a close circle of friends. Now, if that’s all-”

“What about enemies?”

“There’s no animosity in this school, Constable. All students are encouraged to be courteous and inclusive.”

“Friends she fell out with, then? Girls she used to be close to and now isn’t? Girls she’s only befriended recently?”

Madeleine’s features hardened. “I’m afraid I wouldn’t know.”

It was like drawing teeth.

“In that case, who would know?”

A pause. “Aiko’s teachers may be in a better position to comment.”

“Who are her closest friends?”

“Bobbi Kentwood.” The answer was fast. Too fast? Madeleine’s knuckles paled, one of her thumbs rubbing small circles into the wrist of the other hand.

“Has she shown any signs of depression?”

Another hesitation. Was Madeleine trying to decide what PR tack was best for the school?

“Not to my knowledge. Nothing’s been reported to me, and I don’t deal with students often enough to have observed anything specific. Look, I’m perfectly satisfied that this was simply an unfortunate accident.”

Another unfortunate accident, Zero wanted to say. Two accidents in three weeks. What were the odds? Instead, she asked, “What about Aiko’s life at home?”

“Her home situation,” the headmistress paused again, eyes sweeping the empty hall, “is complicated. She doesn’t get along with her stepfather. That’s the main reason she’s in boarding school. Her mum is Japanese,” she added as though this explained – what? That her mum was in favour of elite education? That she chose the husband over her child?

“What about her biological father?”

“He died when Aiko was little. I’m not privy to details, I’m afraid. During the entry interview, I could sense that the subject was upsetting for both Aiko and her mother, so I didn’t press.”

“Siblings?”

“None.”

“And the nature of the trouble between Aiko and the stepfather?” Could this be the reason for Aiko’s suicide attempt? Such a stereotype, a hostile or abusive stepfather; and yet it was a stereotype only because it was statistically likely.

“Again, very little was said, and not much more implied. Aiko made a comment about wanting to leave home, said that she couldn’t wait to be seventeen and legally allowed to move out, but she didn’t specify her reasons. She’s fifteen,” she added, sensing Zero’s next question.

“Does she go home for weekends? Holidays?”

“Yes, and yes.”

“This coming weekend was not unusual? She was supposed to go home?”

“Correct.”

Had Aiko not wanted to go home so badly that she’d chosen to take an overdose? No, Zero wouldn’t speculate before gathering all facts. “Let’s go see her bedroom now.”