I bought my first batch of fake followers in 2012.

Around that time, I decided to become a software engineer.

Over the past ten years, my code, methodologies, and business ventures have been responsible for hundreds of millions of illicit automated engagements on Instagram.

I was motivated by currency, curiosity, and clout, and it was easy to justify my duel with the unchecked power of social media platforms. Given all the hours stolen from my generation, why not snatch something back?

I saw how the quirky apps of my adolescence had become inescapably addictive, how Big Tech made a mockery of relationship building, and how algorithms, including algorithms I later developed, rewarded problematic and antisocial behavior. I received declined payment alerts indicating that customers had depleted their bank accounts while chasing popularity on Instagram.

After I started writing this book, a social media startup offered me an opportunity to lead an engineering team that built (controversial) attention-grabbing recommendation and engagement algorithms. I accepted; I was successful. From my control panel, my influence on the platform’s users was godlike. I was stealing their time and getting paid for it.

This book is not a response to the Netflix docudrama The Social Dilemma loosely based on the book, Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe, which was itself a narrative-driven amalgamation of viewpoints contained in a half-dozen tech-meets-sociology books with irritably similar titles.

This is not a research project, long-winded whistle-blow, hit piece, or self-aggrandizing chronicle of my life.

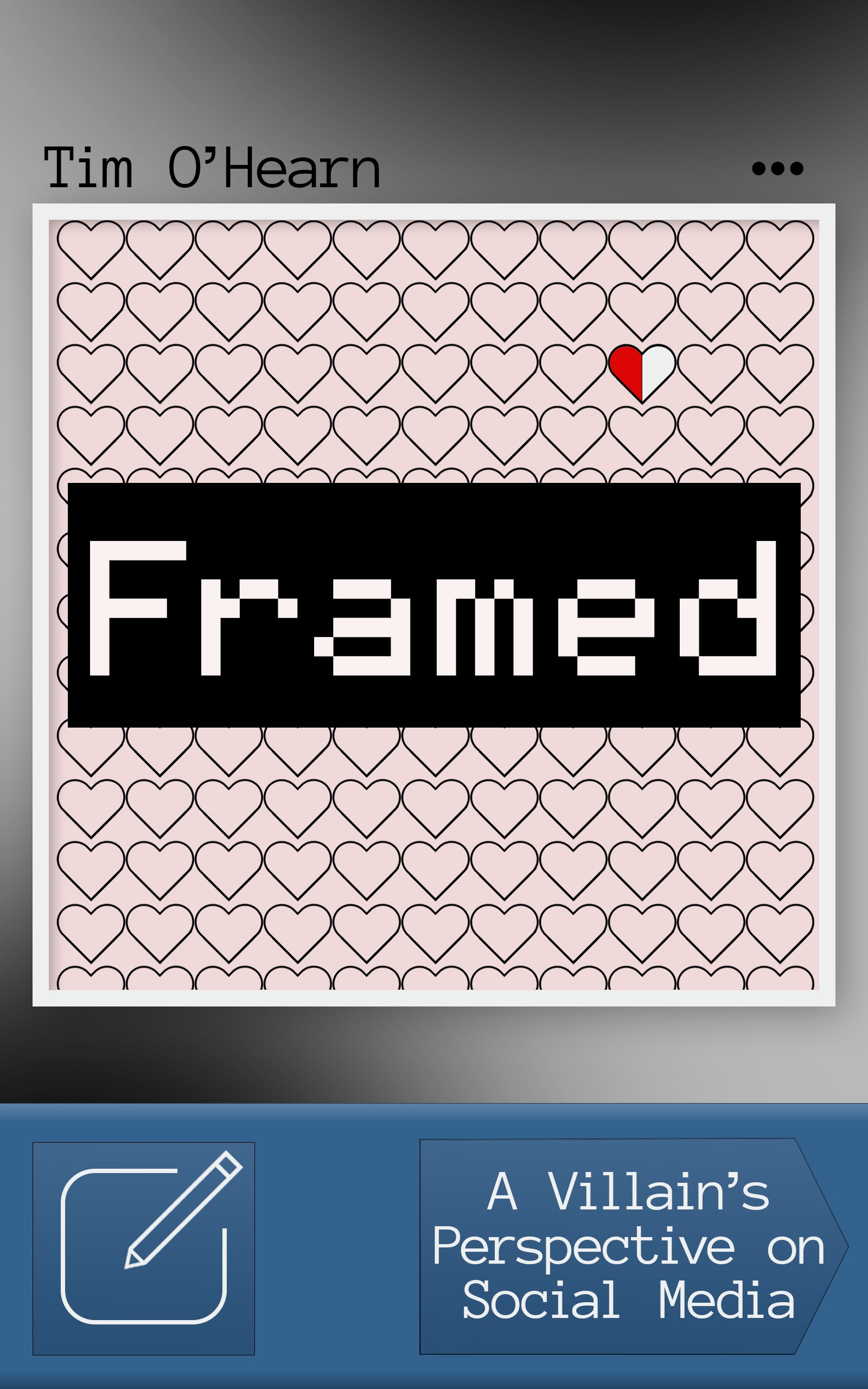

Framed: A Villain’s Perspective on Social Media is a collection of shards and shreds and conspiratorial diatribes penned by a fellow who grew up with the internet, became an adept programmer, and mastered the realm of social media while never being employed by Big Tech.

Four pillars comprise the impetus of this book:

1. Being born in the 1990s, growing up with the internet, and avidly using social media—from Myspace in 2006 to TikTok in the 2020s.

2. Possessing a computer science degree and a grasp of advanced programming concepts, enabling me to analyze social media on a different plane.

3. Having profited from veritable “bad guy” activities on Instagram and other social media platforms.

4. Having led the development of algorithmic recommendation systems, push notification infrastructure, and personalized social feeds at a mobile app startup.

These experiences, combined with an enthusiasm for writing, enough money to finance and create this book free from outside influences, and a modicum of hope that this effort could be a positive force for change, have led this eccentric recluse on an unlikely journey.

This journey has been a confluence of opportunity and ambition, demand and demarcation, rules and rulers and rulings. I believe I have a duty to preserve my journey. Rigor must be applied even when outcomes may be inconvenient. Questions must be asked, and even the most reckless opinions must be shared despite the risk of ostracization.

I meandered into social media automation because I was motivated by vanity and greed. I made money and brushed shoulders with men and women who earned substantially more. This arena of social media marketing (abbreviated as SMM) turned out to be a shadowy realm of value-added services profitable beyond my wildest imagination. This book covers SMM better than any other.

Much content about social media is biased and misleading—paid placements, mediocre books, recycled content, hidden affiliate links, poor punditry, wonky agendas, and perpetual clickbait point to the concealment of sad truths. Making sense of the deluge of spurious information requires technical adroitness, obsessive immersion, and sociological sensibility. There are few journalists bravely tackling these issues.

The villains and those generating massive revenue from services built on top of social media platforms have no incentive to talk. One scoundrel responded to an interview request with, “I'm good bro, hope the launch goes well.”

Social networks, now synonymous with publicly traded companies, must tread lightly. Shareholders get finicky when faced with publicity about the social media underworld or the societal decay caused by their products. At the same time regulators and authorities are becoming daring. Government action, bot takeovers, and bombshell articles from the New York Times cause users to bounce to other apps. Those precious activity metrics, regularly reported to investors, must be upheld at all costs.

I’ve been the puppeteer as well as the puppet. Unhealthy social media use has weakened the fabric of society. People are depressed, distracted, and anti-social. Placing a smartphone in the hands of a child redefines childhood. The middling creatives among us simply transcribe compelling captions and apply neat filters to their photos.

Framed was written for a broad audience. Although elements of my personal experience are present throughout, there is not a cohesive, linear story. For this reason, I’ve split this document into two themes:

1. Tragicomedy: my views on the amusing, dreadful world of social media.

2. Instagram’s emergence and platform misbehavior: an authoritative account of villainy.

Even if the reader acquires a bootleg copy of this book, perhaps with missing material or unauthorized edits, it’s payment enough to flip through the pages and consider the perspectives therein. Today’s world is filled with unprecedented freedom and opportunity ushered in by the Information Age. Reader, regardless of how or when you came across this book, I hope you share the same optimism that technology can improve society.

I also hope that you’ll follow me back.

---

These days, the extent of my involvement with TikTok is that I split an elevator bank with employees of TikTok’s U.S. headquarters here in New York City. Yeah, I work a corporate job. I no longer experiment on users or get paid to make influencers more influential.

When the doors to my elevator close, I’m not thinking about those bright-faced, fashionably dressed sprites in the other car. But, on Friday, January 17, 2025, I was inundated with messages from devotees asking me if there was anything I could do.

“im really gonna miss tiktok”

“i really hope something happens to save it”

“can you save it?”

This was a challenge. Was there anything I had learned from my transgressions against Instagram that I could apply to TikTok’s impending shutdown?

Sure. If it gets shut down in the United States, use a proxy server to maintain access.

TikTok was shut down late on Saturday, January 18, 2025,1 before reemerging the next day. Anyone connected to a proxy in a country other than the United States wouldn’t have noticed.

A long time ago, social networks were seen as fringy, faddish, and fleeting. Some apps eventually encapsulated that by embracing shared media that was temporary—that disappeared. Today, social media is permanent and ubiquitous, and the perhaps most influential platform of them all just pulled a disappearing act in front of two hundred million Americans.

There is an ever-present temptation to crack the code once again, to profit and prevail. I could have used a technique I learned in 2017 to subvert this “ban.” Digital overlords know that I’ve suffered thousands of bans. The sustained interest is not about techniques or our penchant for subversion; it’s about what drives the demand for social media marketing and how, as the hottest apps change, it’s the same bad guys donning different masks.

One of the hypotheses of Framed is that everything about dyadic social interaction on the internet can be traced back to long-forgotten, cringe-worthy practices on Myspace. I see my role as steering people toward my perspective while stopping along the way to pedestal the early internet and the ponderings that befit this medium.

As I wrote this book, I was overcome with the feeling that time was slipping away and that my unarticulated thoughts would soon be irrelevant or disappear from my memory like Snapchat pictures with ten-second lifespans. I held the conviction that all of this was worth writing down.

What Happened Then?

Journalist Sapna Maheshwari learned what black hat Instagram marketing was before I did.

In 2017, while I waited for the phone call that would draw me to the dark side, Sapna and a few million other Instagram users noticed an emerging phenomenon. Unknown and unencountered Instagram accounts were posting generic positive comments on photos.

In her article, “How Bots Are Inflating Instagram Egos,”2 published on June 6, 2017, Sapna posted a honeypot, a bait post: an ordinary picture of the New York Times office. After ten weeks of accumulation, the comments—all positive—included encouragement, like, “best one so far,” “this is cool,” and “very nice” as well as an array of congenial emojis.

Suspicious? Sure. Yet, unlike email spam of the early aughts, pornographic referral, fake merchandise, or phishing scam bots that descended on social media sites in the interim, these Instagram comments were neither voluminous nor an obvious malevolent plot. The accounts typing the comments, handing out likes, and sending “follow” requests seemed normal, even, plausibly, human. As mystifying as it was, people were unlikely to complain about a little extra attention. Sapna suggested that it was “the internet’s most pleasant form of spam.”3

Before I ever earned a dime, Sapna revealed the grand secret of the “cottage industry” I would soon gain admission to, an involvement that would bestow upon me a god complex during my early 20s.

Many people with public accounts on Instagram may not realize that when random users follow them or like or comment on their posts, it is often the work of a cottage industry of websites that, for as little as $10 a month, send their clients’ accounts on automated liking, following and commenting sprees. It’s a rogue marketing tactic meant to catch the attention of other Instagram users in hopes that they will follow or like the automated accounts in return.4

By “rogue” she meant “black hat,” which will be explored in depth later but means simply, “in violation of the terms of service of a website, social contracts, or ethics, without necessarily being illegal.” Automation service providers were liable to be shut down at any time, and any customer paying for a program to run on an account risked an account ban. Instagram’s terms of use made this clear, and much later in this book I’ll address Instagram’s detection systems and the careful balance maintained by technology companies trying to fight rogue marketers.

In the spring of 2017, Instagram’s legal team was shutting down major players. This was well documented. This era, the transition out of which Sapna identified, is what I call the “Instagress Era” because Instagress was the dominant service provider. Instagress was a software-as-a-service control panel from which customers could connect their Instagram accounts, configure who or which hashtags they wanted to target, enter a few generic comments, press play, and then watch as the reciprocated actions tallied up.

Instagress provided a dashboard with toggles for automating “likes,” “comments,” “follows,” and “unfollows” which updated live as the actions accrued.

Instagress and what I call “Instagress clones” were particularly dangerous because these online platforms provided disruptive automation tools to people who would otherwise have no idea how to lob flattering spam across cyberspace. The results were so outrageously good that mediocre Instagram accounts could gain two thousand followers per month. This encouraged Instagress customers to create additional Instagram accounts (for example, for their pets) to sign them up for Instagress and passively let them grow. Not only was Instagress’s pricing absurdly cheap—$9.99 per month5—but the service also offered bulk discounts to run multiple accounts.

The systems that debuted in lockstep with Instagress were nothing more than illicit advertising services. That a ten-dollar-per-month service could provide dramatically better results than running advertisements was not only disruptive, it created a natural conflict between users and Instagram. It is difficult to uphold integrity and convince anyone to purchase ad space when third-party services can instantly deliver fake likes or convincing, organically acquired likes at a fraction of the price.

In 2017, this shadow industry generated well over twenty million dollars. The vast opportunity attracted other talented programmers, which spurred a game of “Whac-a-Mole.”6 Instagram’s legal team sent cease-and-desist letters, but the same underlying technology was being re-skinned and relaunched a week later. If one team moved on, another group stood ready to take their place in search results.

One may wonder how software engineers could log into Instagram accounts and execute these actions. They reverse-engineered Instagram’s private API and encoded browser automation functions that interacted with its web client. It’s out of the scope of this essay, but I’ll reintroduce it in “Hackathon Hackers” and the following chapters.

The post-Instagress era bred copycats. It also added another layer of deception. Instagress customers knew that they were paying Instagress to run a bot. By prying into Instagress’ marketing materials and website, Instagram could easily identify that it was an automation service. The next generation of providers realized that “bot,” “automation,” and “guaranteed” were dirty words, so they leaned into assurances of “organic growth” and “compliance” and inferred the presence of human operatives.

Rather than providing customer dashboards like Instagress did, successors collected targeting information at signup using basic web forms. Behind the scenes, they ran bots and fine-tuned them using rough inputs of the information submitted at signup. It still worked well! The key difference was that an investigator couldn’t easily glean the automation from the website copy or scant resources provided to a customer after signing up. Gullible customers deluded by the branding would be surprised to find their accounts banned for violating Instagram’s terms of use.

The article referenced an April 6, 2017, post by photographer Calder Wilson who had run Instagress on his personal account.7 In some ways, Wilson’s “I Spent Two Years Botting on Instagram – Here’s What I Learned” is a synopsis of the Instagram portion of this book. Some of his lines of inquiry have been left unanswered until now.

Although Instagress and its successors pushed a relatively new, “organic” type of botting, in the late 2010s, “obviously fake” bots were also rampant on social media. No article covered this phenomenon of annoyance and deception better than the New York Times’ “The Follower Factory,”8 published January 27, 2018. This one is in the hall of fame because the reporting led to the Federal Trade Commission setting a major precedent.

Fake activity conducted by bot accounts on Twitter was out of control despite being easily identifiable.9 The article shined a light onto a multi-million-dollar industry and one of its largest illicit operators, U.S.-based marketing company Devumi.

Devumi earned millions by selling fixed amounts of “real” followers to a massive list of clients, including already notable, if not objectively famous, individuals.10 The “shadowy” black market for attention was hot. The customers’ desire for any publicity meant a deluge of willing interview subjects.

Upon closer inspection, it was determined that followers were fake “bot” accounts created and controlled by bot “farms” (or, befitting the title, “factories”) in far-flung countries, such as Pakistan. These software agents exhibited predictable patterns of spammy behavior.11

Crucially, Devumi had no software engineering operation. The small firm was not creating the accounts and did not directly control the behavior of the following accounts. Devumi was merely a well-designed storefront from which U.S.-based customers ordered likes and followers from sergeants who commanded vast armies of virtual shills. One thousand Twitter followers on Devumi cost an unsophisticated customer seventeen dollars.12 Those same thousand followers, obtained in a larger order from a considerably sketchier “SMM Panel” originator, cost “little more than one dollar.”

My essay “Social Media Marketing Panels and Sockpuppet Botnets” provides a breakdown of social media botnets and shill networks.

The typical U.S.-based followers purchaser wouldn’t have been comfortable navigating the web of cheap but illicit purveyors of fake bulk activity. Ingenious resellers cleaned up the pitch and pushed a central deception—followers were created by real people, represented real people, and behaved like humans.

Aside from Devumi being built on a foundation of lies (which was covered in a later piece, “Faked: The Headquarters. The Followers. The Influence?”), “The Follower Factory” identified another transgression. Instead of pushing bot accounts without profile pictures and with usernames composed of jumbles of text, the overseas creators scraped and used pictures and names from real Americans’ Instagram accounts.13

The risk of impersonation on an industrial scale was scary—ominous. What seemed like an illicit but perhaps harmless scam pulled on Westerners desperate for followers became scarier. Through all of this, Twitter appeared culpable—aware of the issues and unwilling to stop them.

Why would Twitter not aggressively purge these practices? The company’s quarterly reports and bottom line benefitted from the daily, weekly, and monthly active user numbers inflated by bot activity. The conspiracy was that there was a careful balance to be sought. Robots counted as “active” users helped the platform in one way but caused all types of user strife. Catching ninety nine percent of bots instead of eighty percent of bots was extremely expensive, and could have impacted human signup and in-app experiences. A suspicious imbalance on the platform led to a dispute during Elon Musk’s 2022 bid to buy Twitter.14 Compare the stratospheric valuation of a social media platform concealing automation activity to the pitiful perception of a social media platform overrun with bots and consequent alleged phony metrics.

Social media platforms have the same complicated relationship with spam bots that the U.S. Postal Service has with junk mail.

While reading and rereading “The Follower Factory” early in 2018, I felt like a character in a detective novel (spoiler: perhaps not the detective). At that point, I had been contributing to a shadowy follower growth business for almost six months. That operation was responsible for the types of activity recounted in “How Bots Are Inflating Instagram Egos.” Crucially, that business did not sell fake followers. It was not directly impacted by the legal precedent that would be set by the New York State Attorney General.15 The article and resulting commotion provided information that would-be profiteers used to map the true size of the market.

The alternative to rampant fake account creation and puppeteering was to log in to a real account and automate its actions. Rather than directing an army of bots to follow a customer, use the customer’s own account to attract modest engagement from other humans—using a bot. This came to be known as “organic growth.” In a way, organic growth was the righteous path. If I log into a customer’s Instagram account and start liking photos and leaving comments, that customer will receive likes and comments in return and enjoy a boosted social status. In the aftermath of the NYT exposé, business boomed.

Two months later, the New York Times covered Instagram again with an article about Instagram bots.

Empowered by the response to the article about Twitter misbehavior and surely benefitting from a flood of unsolicited tips from social media “experts,” Sapna Maheshwari picked up where she left off in 2017 to address troubling Instagram activity.

“Uncovering Instagram Bots With a New Kind of Detective Work” was published on March 12, 2018.16

This article didn’t make as much of a splash in terms of cross-coverage or legal precedents but did stoke quite a bit of action that was never attributed to its publication. There weren’t any follow-up articles of significance; the reader could have believed that attention had shifted elsewhere. Was that true?

My attention did not waver. March 2018 marked a breakthrough month for both my business and rogue Instagram growth. I saw revenue nearly double from the previous month, likely from customers who had just heard about the dark side of social media marketing. I have documented that a massive number of savvy entrepreneurs started software-assisted businesses around that time. In all, I’ve analyzed over one hundred such services.

Over the next few months, Meta did take notice and strictly policed fake accounts and botting on Instagram. I refuse to believe that this was the result of anything but pressure from this New York Times article.

I have never forgotten one of its leading quotes from the co-founder of a firm that had developed special methods to detect bot activity: “The amount of bot activity that’s happening on these platforms is pretty insane.”17

Another founder of a social-media-adjacent firm used the phrase, “day of reckoning” to refer to advertisers who, while planning to run influencer marketing campaigns, suddenly got squirrely in the face of evidence that accounts had inflated their metrics.18 Their followers were not real. Fake followers are deadweight—they’re impervious to persuasion.

One of the early companies performing this type of “detective work” claimed to use over fifty metrics to identify fake accounts.19 Although the examples resonated with me, the underlying fact was that the company analyzing the accounts was probably violating Instagram’s terms of use. To analyze such metrics at scale, a provider would have had to query Instagram’s private API and scrape data from the platform!

My framing is that even some of the good guys were bad guys.

Sapna did say that “changes to algorithms on Facebook and Instagram have significantly reduced the number of people who will see a person’s posts without paid promotion.”20 Later, I’ll share my thoughts on these algorithms and, lest we forget, the “rogue” marketers who design systems to exploit them.

What Happens Now?

Social media journalism from the New York Times in the late 2010s continues to fascinate me. I revel in each re-read. I hope Framed is as thought-provoking and entertaining as those articles were. When people ask me “wHo’S yOuR aUdIeNcE?” I paste parts from dozens of books and hundreds of articles and research papers that inspired me.

This audience exists because I stand on the shoulders of brilliant investigative journalists, talented researchers, uptight encyclopedists, random bloggers, and Urban Dictionary ethnographers—the serious weirdos who took the time to write things down.

The scope of this book will likely be regarded as absurd for one person with no traditional support team to attempt. I rush toward publication in fear of being forced to lodge an opinion about the new social media site.

There have been cheaters, thugs, and even genuine criminals misusing social media platforms since the days of dial-up. We never got to read their stories. It may seem like there’s a podcast episode and YouTube deep dive dedicated to every grifter who has ever lived, but we’ve done a shitty job of preserving the history of the internet. Some of my fondest social media memories are of events, personalities, and sociological topics that haven’t been archived anywhere. So much has actually been “shut off.”

Why not try to connect the dots between the niche I know so well and the zeitgeist that many intellectuals sink their teeth into only when the ocean turns dark red?

When I revealed to friends that they hadn’t seen me in a year because I was covertly writing a book about social media iniquity, several suggested, “Oh, you need to break up the chapters and post promotional videos on TikTok!” To them and to readers I say that to make such a suggestion is to totally miss the point. If the reader does continue and entertain my brazen attempt to connect those dots, it will be clear why.

I can’t predict the next wave of cultural rewiring or if it will occur on smartphones or the metaverse or a dimension not yet imagined. The modern incarnation of TikTok didn’t exist when I started assembling this material. There is an argument that Instagram’s relevance is waning. I’m not active on social media these days, and all my ventures have been closed.

I want to crystalize my perspective before it really is too late. This perspective was gained not while I was on the outside looking in but while I was dead center in that four-cornered frame looking around. I can’t be sure what I’ll find the next time those elevator doors open.

1. CNN Business, “TikTok Shuts Down in the U.S. After Federal Ban Takes Effect,” CNN, January 18, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/01/18/business/trump-tiktok-ban/index.html.

2. Maheshwari, Sapna. “How Bots Are Inflating Instagram Egos.” The New York Times, June 6, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20250217042425/https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/business/media/instagram-bots.html.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Wilson, Calder. "I Spent Two Years Botting on Instagram – Here’s What I Learned." PetaPixel, April 6, 2017. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20190509221830/https://petapixel.com/2017/04/06/spent-two-years-botting-instagram-heres-learned/.

8. Confessore, Nicholas, Gabriel J. X. Dance, Mark Hansen, and Richard Harris. “The Follower Factory.” New York Times, January 27, 2018. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20250112143607/https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/27/technology/social-media-bots.html.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. O’Brien, Matt. “Elon Musk’s Twitter Troubles Could Have Big Impact on Media.” AP News, October 31, 2022. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20250129030026/https://apnews.com/article/elon-musk-twitter-inc-technology-business-12632270af1547933d41ffc50f3012ba.

15. New York State Attorney General. “Attorney General James Announces Groundbreaking Settlement with Sellers of Fake Followers.” New York State Attorney General, January 30, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20250213223749/https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/2019/attorney-general-james-announces-groundbreaking-settlement-sellers-fake-followers.

16. Maheshwari, Sapna. “Uncovering Instagram Bots With a New Kind of Detective Work.” The New York Times, March 12, 2018. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20241231201828/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/12/business/media/instagram-bots.html.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

Comments

For the unitiated this could…

For the unitiated this could be a very demanding read but for those 'in the know', I have no doubt that this contains all the necessary ingredients for success. Good luck with it.

This book has a brilliant…

This book has a brilliant start. I am certainly engaged with the topic. I would love to know what you have to offer. A round of edit can elevate the book further.

Niche audience needed

I don't know that this will appeal to the masses, but if you find the right audience, I think they would enjoy it!