WHAT IS HMONG FOOD?

Getting Up

Dear Reader,

When I was younger and people asked me “What is Hmong food?” I would cringe while telling them we ate freshly killed chicken at home. We would pluck and chop it and boil it into a soup with the feet and head included. I felt embarrassed by the monotonous routine of eating rice at every meal, where breakfast consists of reheated leftovers, eaten with a side of Thai chili pepper with fish sauce. There were no eggs, bacon, or pancakes, not even cereal. I didn’t want to tell them that at family events we ate raw ground pork laab and beef stew made with gizzards, liver, intestines, and blood. The image of a shaman sacrificing a pig filled my mind. I definitely could not tell them that.

I often started my explanation with, “Well, it’s not like Thai food or Vietnamese food or Chinese food. It’s kinda like Laotian food but not really. It’s, you know, Hmong food.”

They would persist. “So, what do you eat? What are some dishes you make?”

“Rice. Pork with mustard greens soup. Chili pepper with fish sauce. Chicken soup with herbs.” I kept it safe and simple.

“Herbs like basil, oregano, and thyme?”

“No, Asian medicinal herbs. I don’t know what they’re called in English.”

And that was how I struggled my way through describing Hmong food.

In these interactions, I tried to keep as much of my heritage hidden as possible. I was ashamed of it.

At the table during mealtimes, we kids had our American dishes, and the elders stuck with their own. The elders used to tell us, “Thaum yug laug zog, yug yuav paub mov zoo noj yog le caag,”—When you are older, you will know the taste of good food. Meanwhile, they’d be eating sautéed bitter melon with green onion and cilantro, and nqaj tsawg, pork stew that included the liver and intestines, slow-cooked with a bunch of herbs and aromatics while we children stared into our bowls of hot dogs and rice with ketchup. I knew there was no way I would ever trade that for bitter melon and nqaj tsawg. To us, their food was from the old country. It took hours to prepare, smelled of grass and gizzards, and tasted bitter and bland at the same time.

I didn’t start cooking until I was in college, and even when I did, for a long time I didn’t cook Hmong food. Compared to the rich flavors of Thai and Indian food, the romantic subtleties of Italian and French dishes, and the exotic aromas of Jamaican and Ethiopian spices, my own cuisine held little interest for me. It wasn’t until I was in my early forties that those hidden parts of me emerged. The food Mom implanted in my soul burst forth, inhabiting my hands, my tongue, and my nose.

I became curious about Mom’s dishes. I was hungry to know how she tasted food, how she made sticky rice cakes and sugar cane syrup, or what winter squash she used for the kua taub hau she ate at every meal. Her kua taub hau acted as a palate cleanser between dishes and was a more nutritious substitute for water. I wanted to know the taste of fresh tofu made with soybeans.

She showed me how to make nqaj qab, chicken soup: how long to boil the chicken, how much salt and black pepper should go in it. These became the food I missed when I was away from home and the dishes I started to make to nourish my soul.

Maybe it’s an age thing. Or maybe my taste buds had finally arrived, like the rice that “arrives” when it’s steamed twice. But as the elders had said, I was finally waking up to the taste of good food.

Eating, for us, is more than just nourishment; it’s an act steeped in meaning, a way of existing in the world. When I sat down to work on this memoir, I found that these recipes didn’t start with ingredients or measurements. No, they started with memories, each dish a story I could taste—who I was with, how I learned it, where it came from. It began with the aroma that enveloped the kitchen, with Mom walking outside to her garden to gather the necessary greens and herbs, coming back with things I had grown up with but couldn’t name in English. As I flipped through memories of the dishes I ate as a child and wrote out recipes, I realized that I was learning about myself, about my mother, and about my people’s culture and history.

I became the food I was writing about.

So, what is Hmong food?

Hmong food brings us back to our true nature. It brings us home to our body.

Hmong food is the essence of the earth: simple, with nothing extra. Use everything, eat seasonally, and eat what we grow. Hmong food is not designed to tantalize the palate; it is meant to nourish and give us energy for the day. Hmong food is food from the soul, for the soul.

Hmong food restores us to our roots. It slows us down to touch and taste our food. It strips away the oil, the sauces, the heavy, dense flavors that we as a culture have piled on top of life, and takes us back to the purity of each ingredient.

When you cook Hmong food, you connect with the earth’s natural cycles. Every Hmong family tends to a small patch of herbs, either in their backyard or, if space is limited, in buckets outside their front door. Using these home-grown herbs in your dishes not only links you to the soil but also to age-old traditions and the rhythm of the seasons. You feel inspired to plant a bucket of lemongrass in your yard.

When you eat Hmong food, you’re consuming more than just food. You are eating the memories, the history, the courage, the strength, the resilience, and the love of a people. You can’t eat Hmong food without learning something about our history and culture. When you eat Hmong food, you become part of a lineage that passes recipes orally from grandmother to mother to daughter, connecting generations. It is a lineage whose heartbeat connects one person to the next. It is the interdependence within the community that keeps the food alive.

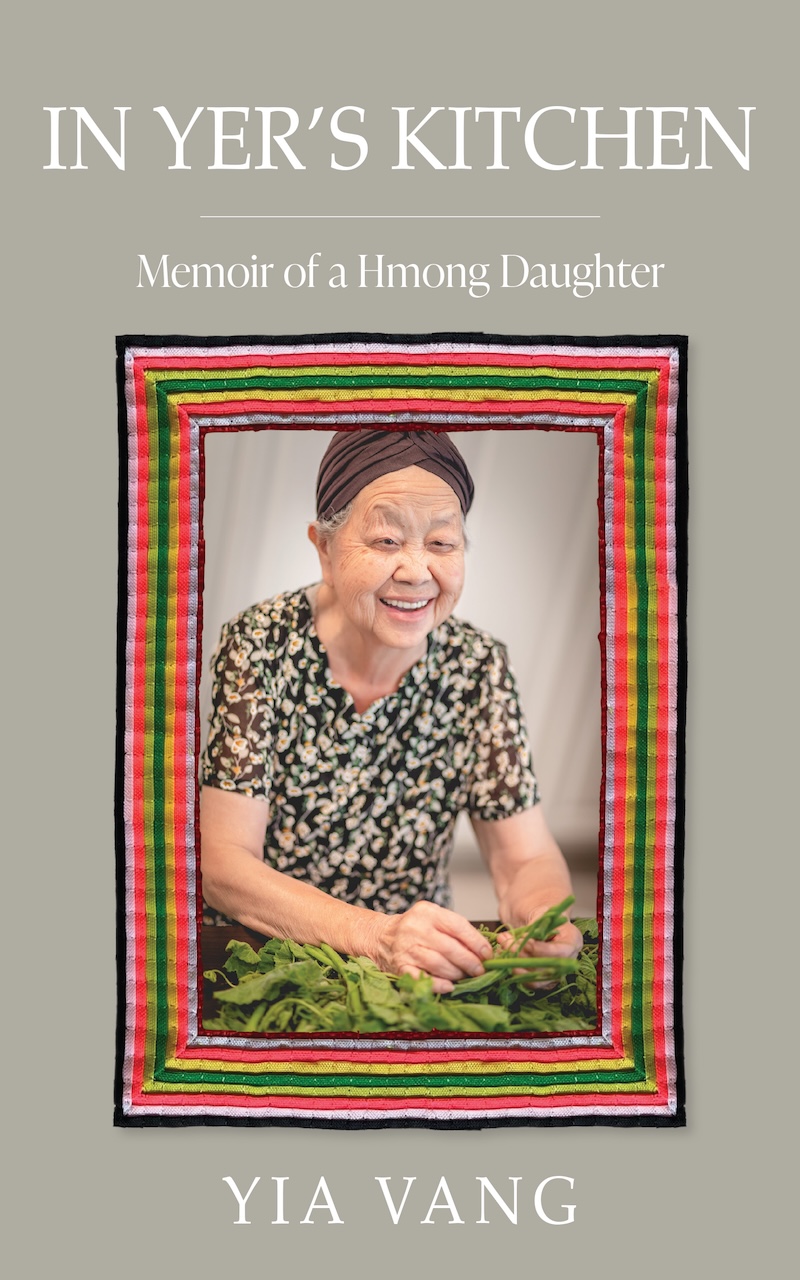

What began as a cookbook of Mom’s recipes evolved into a memoir, one that seemed to have come from a fairy tale about a girl from a mystical land. Except that it was very real. This became a book diving into the complex, interconnected relationship between mother and daughter that can be witnessed across all cultures and throughout time. It explores the inherent challenges of these fixed identities and serves as a road map for navigating the intricate path of finding one another. This became a love story between a Hmong woman and her mother.

For my Hmong brothers and sisters, I hope it will awaken your own childhood memories and dissolve any lingering shame about who you are. It is not us who did not understand the world, nor is it us who are too “barbaric” to inhabit more civilized cultures. Rather, people do not have the refinement of heart or depth of vision to appreciate the richness of our culture. We are not meant to be boxed into a dominant culture’s ideas of civilization, success, and order. We are to awaken people from their delusion and disconnection from the natural world and show them the way home.

For the non-Hmong readers, there was a time when we were connected to the earth, when life came alive with flavors and textures, simply by adding salt to a dish. The body is home, and home is the place where our soul wants to return. The Hmong way of cooking and eating is a path to rediscover that connection, reviving your senses and nourishing both body and soul.

It has been a journey for me to arrive at home. I hope the recipes and memories in this book will comfort you in your own journey home.

Lug noj mov. Come eat.

RICE CAKES

In Love with Mom

The first time I fell in love with Mom was when she shared about her trip around the world to see her eldest brother, Uncle Fang, in France in September 2008. He was terminally ill and lived out his last few days surrounded by his family at home. Uncle Fang passed away a week after Mom and Aunt Green arrived, as if he had been waiting for them to be there by his side when he crossed over.

× × ×

Mom had six sisters and two brothers. She was the ntxhais ntxawm, “youngest daughter.” Her father passed away when she was too young to form any memories of him. She was raised by her mother and her siblings, who loved her deeply.

Mom was born deep in the jungles of Luang Prabang, Laos, where the tips of the mountains disappeared into the clouds. She was born in a village that does not exist on a map. On a mountain that remains a mystery as she tells me its name and the name of the river where she fetched water. She was born at a time and place where there were no calendars, clocks, or electricity. She was born in an unknown month in an unknown year.

Mom grew up with the waning and waxing of the moon, with the cycles of the harvest seasons. One season followed another. She grew up with pots and pans as her toys, thread and needle and fabric as her writing tools and books. The acres of land where the food was grown was her playground. As soon as she was old enough, Mom walked next to her mother to the river to carry water in thick bamboo pipes strapped to her young back. Once she was capable, she joined her sisters on the farm. She tilled, planted, harvested, slashed and burned, tilled again. Cooking and sewing were her prized skills; patience and attention her most valuable assets.

Mom had no alarm clock to wake her up. Her body would naturally rise and sleep with the rhythm of each day. She stayed in flow from the moment she woke up before the rooster crowed until her eyes drooped heavily under a burning wick dipped in pork oil. In the early morning, she’d start a fire on the hearth. The fire lit up the thatched hut with bamboo walls to awaken the family. She boiled the water for the rice. With only one flame available to cook the day’s meals, it was important to get an early start so that food would be ready shortly after sunrise. They ate, packed a lunch, and set out for the acres of land that needed tending. There was no rest, no checking out, no clock to tell her when to do the next thing.

Mom learned not by asking questions, but through a relationship with her surroundings. She became intimate with her environment, with the crops she planted and harvested, knowing each one by color and texture and smell and the intricate ways they told her when it was time to pick them.

This was the life Mom grew up with into her teen years, next to her mother and sisters, imitating her mother’s intricate paaj ntaub, flower cloth embroidery, under the moonlight after a long day of harvesting, and observing her sisters in the kitchen as they prepared simple meals of mustard greens soup and rice, which she would then replicate.

The natural flow of their family life shattered when communist forces tore into Southeast Asia. Mom didn’t know why we were fighting or with whom. Just that General Vang Pao was recruiting men to help him fight a war against the Xam Lav, Communists. She heard whispers of people called “Meskas” who worked with General Vang Pao. The Meskas were tall men with corn silk hair, and pale skin untouched by the sun. Their hands were large and clean, virgins to the soil. They wore green and brown uniforms the colors of the jungle, with long rifles slung across their backs.

“We are here to help protect your homeland,” Meskas told us.

“We will provide you with weapons and supplies and medical care,” Meskas insisted.

“You will have peace,” Meskas promised. Grown men with wives and children left to protect their land, their family. Some villages dug large underground tunnels to hide fallen Meskas soldiers from the sky.

We had intimate knowledge of the jungle’s intricate terrain. We knew the mountains, every bend and curve and river. We knew the seasons, the rain, the heat, the sun, and the moon. We were brave, fierce, strong fighters. We fought many wars. For centuries, since before the land that is now China existed, we fought for the right to live. In Laos, we were swiftly thrust once more onto the front lines of guerrilla warfare.

Months rolled into years and the men failed to return home, or returned in body bags with their rifles laid on top of them. Their sons picked up their rifles only to meet the same fate. Across the decade, the call extended to even younger recruits: thirteen-year-olds, then twelve-, then eleven- and ten-year-old boys. The death of war is etched into their eyes in faded black-and-white photos, with their rifles towering over them.

In America and the rest of the world, no one knew of the Hmong. No one knew that, in 1964, the CIA started a Secret War in the shadows of the Vietnam War by recruiting more than 36,000 men from Hmong and other minority tribes, training and supplying them with weapons for war. No one knew Hmong soldiers were cutting into the military supply lines along the Ho Chi Minh Trail to prevent the Pathet Laos (the Lao People’s Liberation Army) from transporting weapons from North Vietnam to South Vietnam.

Americans were not told of the total 270 million cluster bombs being dropped into Laos every eight minutes, twenty-four hours a day for nine years. Of those bombs, an estimated 80 million did not detonate when they hit the ground. To this day, millions of undetonated bombs threaten civilians in the mountainside, particularly children playing and running through thick foliage.

Americans were not told that the government released a deadly herbicide, Agent Orange, that rained down on Laos, killing crop and vegetation but also slowly killing those who came in contact with it and leaving behind a legacy of brutal birth defects on an innocent generation.

In 1973, the United States, sensing a lost cause, pulled out of Southeast Asia. To Americans, the government was leaving a war in which it had no business fighting. But Americans did not know that the CIA was still operating in Laos. Americans did not know that the Hmong were now the primary defenders of their democracy. We didn’t fight for political reasons and had no interest in worldly politics. We fought for what we have always fought for—freedom.

Americans did not hear in the news about the 30,000-plus Hmong soldiers, both men and boys, who died without receiving the recognition they deserved from a country that had promised them home, freedom, and peace. Their souls, shattered by the brutal realities of war, wandered lost and untethered through the unforgiving jungles of Laos.

Americans felt the devastation of the communist takeover in Southeast Asia, the domino effect when the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh in Cambodia on April 17, 1975, immediately followed by the fall of Saigon in Vietnam on April 30, 1975, to the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong. An America that was already divided about the conflict in the first place felt the political escalation on its own home front. The turmoil was punctuated on December 2, 1975, when the Pathet Lao captured Vientiane, the capital of Laos.

But America did not know of the atrocities of the takeover by communist forces in those countries until years later. In the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War, there was limited access to information from these countries, and the governments in power tightly controlled media and communications.

America did not know of the estimated two million Cambodians killed under the Khmer Rouge regime.

America did not know of the establishment of reeducation camps and forced labor in Vietnam.

America did not know of the persecution of political opponents and ethnic minorities in Laos.

With no more protection left, the communist Laotian government, with support from their North Vietnamese allies, issued an order aimed to exterminate the Hmong people, sparing no distinction between those who had aided the Americans and those who had not. It marked anyone of Hmong descent as a target, regardless of gender or age.

America did not know of the mass killings, executions, and reeducation camps that descended on the Hmong and other ethnic minorities. Families who escaped death in their villages often met a tragic end in the jungles, where they hid for months or years, succumbing to starvation, diseases, or ambush.

America did not know that for the next decade, a massive exodus took place, when tens of thousands of Hmong fled to Thailand in search of refuge.

America did not know that more than 50,000 Hmong were killed or drowned across the Mekong River in addition to the hundred thousand lives who met their fate at the hands of communist soldiers.

America does not know that, to this day, the Hmong in the jungles of Laos are still being unjustly persecuted, men sometimes taken from their villages never to return; villages blocked from all access to medical care, clean water, and food and left to starve, living off vegetation and wild rodents in the jungle.

Comments

It might also be pertinent…

It might also be pertinent to add: 'America and the West didn't care...' I loved this, having spent many years in Asia myself and now married to a Filipina who cooking and views are much the same. Another edit would really polish this up but even as it is, there is so much wisdom and common sense to be 'digested'. Good luck with it!

It is really well written…

It is really well written. Love the descriptions and relatability (feeling embarrassed about one's own culture, just because it is different from the majority).

Your piece has a warm, personal vibe—like a heartfelt blog article. To shape it more like a memoir, try giving it a clearer storyline. Right now, it flows nicely, but adding a key turning point or a memory could give it more focus. Also, instead of summarizing past moments, try zooming into a few specific scenes—like a kitchen lesson or a family meal—with dialogue and rich detail. That way, readers can really feel those moments with you. These small shifts could make the piece feel more grounded and memorable.

You can tell it's intensely personal

Very well-written, obviously from the heart. My favorite part was: "Maybe it’s an age thing." Because as I get older, I find myself feeling and acting more and more like my mother and understanding her more. So I believe that is a universal, human thing.

Good start!

Strong voice and writing

The writing is genuinely strong, with lovely descriptive passages and relatable themes—particularly the embarrassment some feel about their own culture simply because it differs from the mainstream. The piece has a warm, conversational quality, almost like reading a personal blog entry. To push it towards memoir territory, consider adding a clearer narrative arc with a pivotal moment or specific memory as an anchor point. Rather than reflecting on the past from a distance, try immersing readers in particular scenes—a cooking lesson in the kitchen, a family dinner—complete with dialogue and sensory details that bring those moments to life. The emotional authenticity shines through, especially in observations like growing more like one's mother with age, which feels deeply universal and human. These adjustments would give the piece stronger focus and make it even more memorable.