Chapter One—Running the Atacama Crossing

It’s no time, time.

My running shoes lifted and dropped, lifted and dropped... I was hunched over, my body depleted, just putting one foot in front of the other. I started counting. 1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4. As often happens in a long-distance race, I listened to my breathing and lapsed into a meditative state. Many runners have a mantra they rely on during their run. I count. As my shoes chewed up the kilometres of the Atacama Crossing in 2013, it became the same thing over and over. I call it “no time, time.”

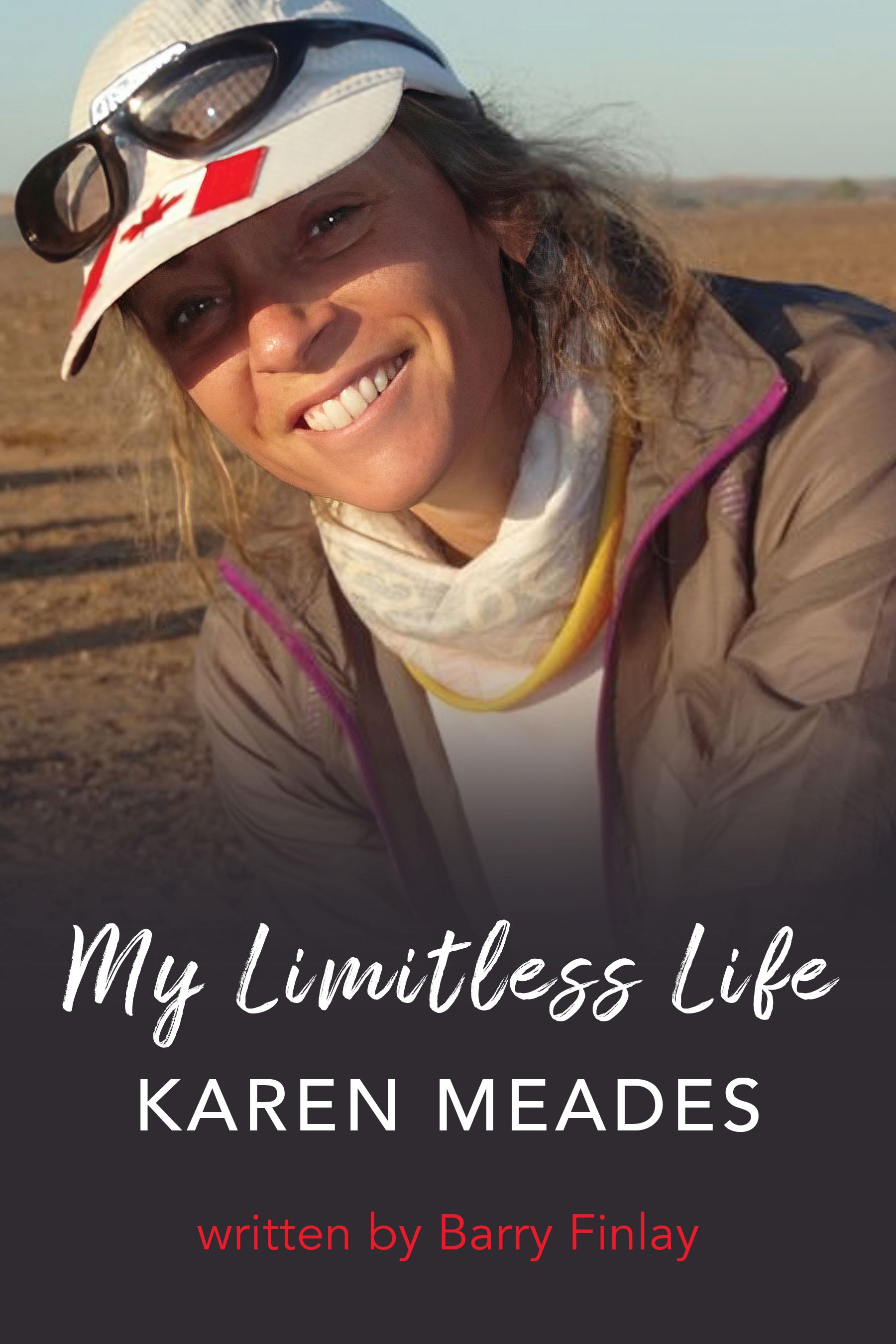

The Atacama Crossing in Chile is one of four six-stage, 250-kilometre, self-supported foot races across the most menacing deserts in the world. I would eventually become the third Canadian woman to complete all four. The four desert races were among the many adventures I’ve been fortunate to have in my 60 years so far.

Sam, my running partner that day, divulged at the second to last checkpoint she was going to quit. Sam (short for Samantha) is a tall, slim, blonde Brit. She’s at least ten years younger than me, and she revealed at one point her parents’ disappointment because she quit everything. I urged her to continue, but I didn’t have the energy to pull her along. I was exhausted but determined to finish, so I had to leave her at the checkpoint, convinced that she would not make it. Sam was one of the many interesting characters I’ve met during my adventures.

I love my life! It’s the adventure that pulls me in, and even if I don’t look for it, it sometimes finds me. Before the Atacama race even started, I was in Edmonton, Alberta, at a business meeting the day before my future husband, Nick, and I were to fly to Chile, where the race was to take place. A severe snowstorm hit, cancelling over 200 flights. Fortunately, mine was only delayed by an hour, and I arrived home in the nation’s capital of Ottawa in time to leave for Chile. It turned out that the storm that had cancelled air travel from Edmonton had affected the entire country, except for flights to Toronto. Woohoo! We must have been living right!

But a look at the departure board at the Ottawa airport revealed delays.

Were we going to get to Toronto in time to connect to Chile? It was a gamble, and I was already excited. My fingers and toes were tingling. I loved this stuff. There was one 10-hour flight to Chile, so either we would make it, or we wouldn’t, and if it was the latter, I wouldn’t be racing in the Atacama Crossing.

Easy peasy! We made it. Our luck was still holding, but how long could it last? Not much longer, as it turned out. The two-hour window to connect to Calama, a small rural area in northern Chile, had closed. We missed the connection. Not even close.

Somehow, Nick thought I spoke Spanish, and I thought he did. Neither of us does. We were in Santiago, Chile, standing at Customer Service, talking loudly to compensate for the fact we couldn’t speak Spanish. It turned out that Customer Service is the same in any country. There isn’t any.

Finally, the airline scheduled a new flight for departure in three hours. We waited for the time to pass. All good! Well, not really. Just as the clock ticked past the three-hour mark, we were told there was a bomb threat at our destination airport, Calama. Yup, a bomb threat at a one-gate, one wooden counter, airport. The airport was closed. We found out much later that someone had left a piece of luggage behind at the airport.

After a nine-hour delay, we were on our way. We arrived at the Calama airport in San Pedro de Atacama in the wee hours of the morning. No problem—two or three hours of sleep, and I was on the bus to the start of the race. Good times.

The Atacama was an immense challenge in so many ways. It’s a physical challenge, for sure. It was also a mental game to push forward without my father. He passed away a few months earlier. Our relationship had been a very interesting one. He did one thing that I give him absolute credit for: he pushed me to face life’s challenges head-on. I thought of him every day in the Atacama. Amid this vast wilderness, I felt tiny and alone. I missed my father profoundly, and I will never replace him in my heart or my soul. I love my father.

Day one of the race started with a bang at 10,000 feet of elevation. To explain the physical effect of altitude, you need only imagine running while breathing through a straw. It doesn’t take long to feel dizzy, nauseous, that sort of flu feeling. In a way, you understand the physical symptoms are altitude, not the flu, so somehow, knowing this makes it possible to continue. I moved a little slower through this day, trying to minimize the dizziness. Feeling dizzy is unsettling.

We were heading downhill over the course of the day, but there were many uphills and downhills. The day was tough, and at the end, I felt that familiar, exhausted feeling. It seems unnatural, but I love that feeling. It reminds me of when I was a kid, when I would play outside all day with my friends, discovering or building something, and by the time I got back home, I was exhausted but so satisfied. The only difference is that now I’m in the middle of Chile, running a race at 50 years of age. Well, really, I was 49, but it had been a long day.

After passing through four checkpoints where the organizers provided water (no other nourishment), we ended the day at a base camp. Organizers provided tents at the base camps, which I shared with an eclectic group of ten people of various ethnicities and nationalities. Two, including Sam, developed an instant dislike for each other and had regular yelling matches, complete with swearing and everything. I wished I had a video camera.

Others in the tent included a schoolteacher, a mathematician, a doctor, an elite Korean ultramarathoner, and a South Korean marine. I told them I was an accountant. Yup, a real conversation stopper. Let me add, the night sky was spectacular—I have never seen so many stars. I can see the Milky Way!

I felt alive on day two but rusty. It turned out to be harder than Day One. I marvelled at how the organizers do that. It starts with a steep descent into the stunning Atacama slot canyon. The initial descent to the canyon is nuts. It strained my knees and feet, but worse yet, I’m afraid of heights. Really afraid. We were too close to the edge. Ohhhh, my Gosh! I had to focus all my attention to get to the bottom without toppling off the cliff into the river below.

Once into the canyon, a fast-moving river fed by mountain glaciers filled the space from one side to the other, so we had no choice but to go through it. The river is freezing cold, and we crossed it multiple times up to our knees and higher over four or five hours. Climbing up and down and crossing, then up and down and crossing. The climbing involved securing a grip with wet running shoes on slippery rocks, using my hands and bottom to move from one rock to the next. You get the idea. The climbing became even more difficult because my feet and calves were numb. The outside air temperature was 50 degrees Celsius (122 Fahrenheit). When we crossed the river, it felt like my upper body was in an oven and my legs in a freezer. Oh, yes, and there was still no air. I was still sucking through a straw.

The rock face of the canyon is a startling reddish-brown colour. With natural creases, swirls and jagged edges carved by centuries of wind and rain, backlit by the brightest blue sky I have ever seen, it offered breathtaking views.

You ask, “Why do I do this?” I bet you know the answer now.

So beautiful. So torturous.

I met another Canadian at base camp at the end of day two. Jim told me he was a colon cancer survivor, which inspired me. His doctors told him his cancer had returned and scheduled him for chemo, but he took a slight break to head to the Atacama Desert. I thought of Jim and cancer and life as I gazed at the stars overhead. When I climbed back inside the tent, I half listened to my two companions fight as I fell asleep.

I know why I do this. I know.

The winds came down from the mountains about 3 a.m. It was so cold and windy it woke me up. The sleeping bag I had just wasn’t warm enough. I had no extra clothes to throw on since they would be too heavy to carry, and I couldn’t close the “window,” so I shivered. It builds character, they say.

Day three was harder still. What is it with these race organizers? We were told we had to run an extra 14 kilometres because of flash floods that hit Atacama earlier in the year. We ran through aptly named “crud.” It’s a mixture of salt crust and dried mud. It resembles a field with parched grass, but it’s hard-packed, uneven ground, and the grass tufts are as hard as wood. The edges cut the bottom of my running shoes and tore my gaiters (the material glued to the top of my running shoe to keep the sand out).

My father had always made my gaiters. This is the first time I made them, and they held up, except for the small tears. Nick helped me—he rocks. As I ran, the crud would stick. When it fell off, I dropped three or four inches. My ankles ached, and there was a large, black bruise on the bottom of my foot, not to mention the cuts on my shin. Still, I’m in complete awe of Mother Nature’s capabilities. I tried to notice as many details as I could, to take a mental picture to hold and keep in my mind.

I am so lucky. I am so grateful!

At the race debrief at 7:30 the next morning, an organizer told us we were about to enter the Atacama salt flats. The flats are about 15 kilometres of the total distance of the day, and over the eight years the race has been ongoing, competitors had pounded down the salt and created a trail that astronauts could see from space. I think that is so cool.

But the salt flats come with a dire warning.

Do not enter the flats if you do not feel confident you can make it out. That’s what they said. Do not enter the salt flats if you do not feel you can make it out. The organizers added it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to come and get us in the salt flats. Gulp! Okay, then.

It would make sense to go through the salt flats first thing in the morning when we are fresh, right? Or at least as fresh as we can be on day four of a 250-km race. Nope! We have 10 or 15 km to go before the salt flats.

Despite the challenges the organizers threw at us, my dad would want me to finish the race. I could hear him. “There’s my little Karen. Everyone else is quitting or dropping out, but there she goes, right to the finish line.” I could see him smiling at me. He always encouraged me to follow my dreams, even though he didn’t follow through on his own.

Well, the salt flats came and went. It was hot, and the flats were a very unusual terrain with a crust on top of soft brown sandy earth. When you break through the crust, you fall into the soft earth/dirt/sand. It’s hard on the ankles and the bottom of the feet, but about halfway through, it’s breathtaking. The salt flats are part of the earth that is protected, and the only people who enter are the Atacama race participants. It occurred to me I was only one of a few thousand human beings who had been in the middle of the salt flats.

But the most incredible part of the day occurred as I approached the last two kilometres. Tourists had descended from a bus, and they were busy taking pictures of the Tebinquinche Lagoon. It resembles two eyes if you are looking from the sky, so it’s easy to understand why people would want to take photos.

The incredible thing is that one tourist is Nick. It was crazy! To think he would be on the tourist bus at the exact time I arrived at the checkpoint had to be serendipity. I screamed and raced toward him, almost running him over. I was so spicy, dirty, tired, at my wit’s end, but I ran into his arms, feeling happy, energized, laughing, and motivated. His tour landed him here at this time on this day. None of it was planned. I was so happy. I loved him so much. We talked about what was left of the race—a long stage and a short village run, and we planned to meet at the finish line. I was on the moon.

Day five took me 23 hours and 40 minutes. Seeing Nick energized me to where the stage was uneventful. I can’t say it was hard, other than being long—just long—longer than long. In the middle of the night, all I wanted to do was curl up at the side of the trail and sleep. I started to fall asleep on my feet. It felt like I was falling. Then, I would wake with a start and an adrenaline rush. The cycle repeated until daylight. When the sun rose, it seemed as though I just woken up and I had this renewed energy. It was very interesting.

The last stage was 16 kilometres. I finished it with another runner in an hour and 20 minutes after we passed through the lovely village of San Pedro de Atacama. The other runner was Sam. A male runner had carried her knapsack from the checkpoint where I left her to the last one before the end, and she and I finished the race together. She confided it was the only thing she had ever finished. I believe she left the race empowered by her experience.

People cheered along the route, and Nick was waiting at the finish line. As I approached, I saw him immediately. I was so happy to celebrate the end of the race with him.

The Atacama Crossing is at the foothills of the Andes mountains and is 50 times drier than California’s Death Valley. It threw everything at us, from sand dunes that stretched for miles on end to glacial rivers, scary high altitudes to salt flats, slot canyons, and more sand. It was as if we were at the beach, except instead of lying on a lounge sipping a margarita, we were running in the middle of a desert.

What an incredible adventure.

The Atacama Crossing was one of several adventures I would undertake in my life. In fact, my entire life has been an adventure. I think of life as a story. I’m creating the story. I visualize myself at an old age in a rocking chair telling my story to my grandchildren, and I want my story to be one I’m proud to share, an exciting story with intrigue, love, adventure… a kick-ass story!

Your story should be about knowing what you want from life, rather than complaining about what you don’t have. It’s a positive orientation to life. Fill your cup. It’s planning for what you want, putting the big building blocks together, and managing the details as they come along. It’s setting goals that are “right sized” for you, then surrounding yourself with good friends and mentors that support who you are and what you are trying to do. From there, preparation and training will get you just about anything you set your mind to.

This has led me to the most wonderful adventures. And, at the end of each one, I take time to reflect on the experience, to learn and course correct. This memoir is part of that process, writing my thoughts, emotions, experiences, and learnings on paper. Then reshaping, so the next adventure is even better.

My adventure started with my upbringing.

Chapter Two—Early Influences: Aunts and Uncles

I was born in 1964, the year the Beatles invaded America, and the Warren Commission declared Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. I’m proud to say the person I became is always positive and likes to step outside her comfort zone. I love to challenge myself, enjoy my adventures, and learn from my experiences. My upbringing deserves a lot of credit for that. My parents, grandmother, the uncles I lived with, two of my aunts, and my teachers all had a hand in making me the person I am today. In some ways during my upbringing, I learned how not to do things. They weren’t always easy lessons, but they were all valuable in shaping who I became.

Comments

Despite the magnitude of…

Despite the magnitude of such an astonishing achievement, doing it is one thing but writing about it is another. Like the amount of energy expended in its completion, it left me feeling a bit exhausted myself. The build-up with the doubt of making the race on time doesn't feel dramatic enough to really appreciate what's at stake. Conversely, I would argue that the race itself ends so quickly that I was denied the experience of actually 'being there', of suffering alongside her as she struggled to overcome one obstacle after another. In fact, it felt a bit too easy! Focus more on showing and less on telling: the devil's always in the detail, even if it's a bit gross.

It's wonderful that you've…

It's wonderful that you've chosen to tell this story; it’s one that truly deserves to be heard. That said, it needs to be conveyed in a way that fully honors the protagonist’s struggles. Like my co-judge Stewart, I believe we need to see more through the visuals and emotions. I’m certain there’s much more you can show.

Interesting!

Even after that, I'll never understand people who enjoy that. LOL The entire first part felt like we climbed up and up and up with little relief. It was hard to find a place that I could pause and take a deep breath away from the intensity. It makes it a little hard to read. Not bad, really. Just...difficult.