From the Desk of the Editor

“When things are good, they’re good, and when they’re bad, they’re bad.”

We start this edition of the Journal with a saying so thoroughly true it sounds stupid. Yet, in February of this year, at the lightless bottom of a personal valley, I sat side by side with my good friend Mira Orlando as she tried to explain to me the galling logic that underpins something so simple. When things are bad, she explained, it’s impossible to arrive at anything good. It’s impossible to even hope for anything good because there is nothing good. It’s foolish to wish for something that doesn’t exist, and foolishness, you see, is bad.

So go the proofs, on and on, and Mira, with her narrow fingers and her slow way of talking, pulled them out onto the pages like a spinner at a loom. And I remember thinking: I don’t want to be here; I don’t want to have to be learning all this again. But there I was. The bad times had come. And when things are bad, they’re bad. I had no choice but to heed their call. So, I set aside my plans for happier things, took up my pen, and returned to my most reluctant duty—that of the editor of The Journal of the Center for Applied Hopelessness.

Yet perhaps in this, I had the easiest job. It fell upon our contributors to disembowel themselves for our observation, for it is here at the Center that we must parade the worst parts of ourselves like the banners of some defunct aristocracy. Why we do this is unclear except maybe we sense that by raising these flags we might better see each other through the gloom. When things are bad, they’re bad, but at least we are here together.

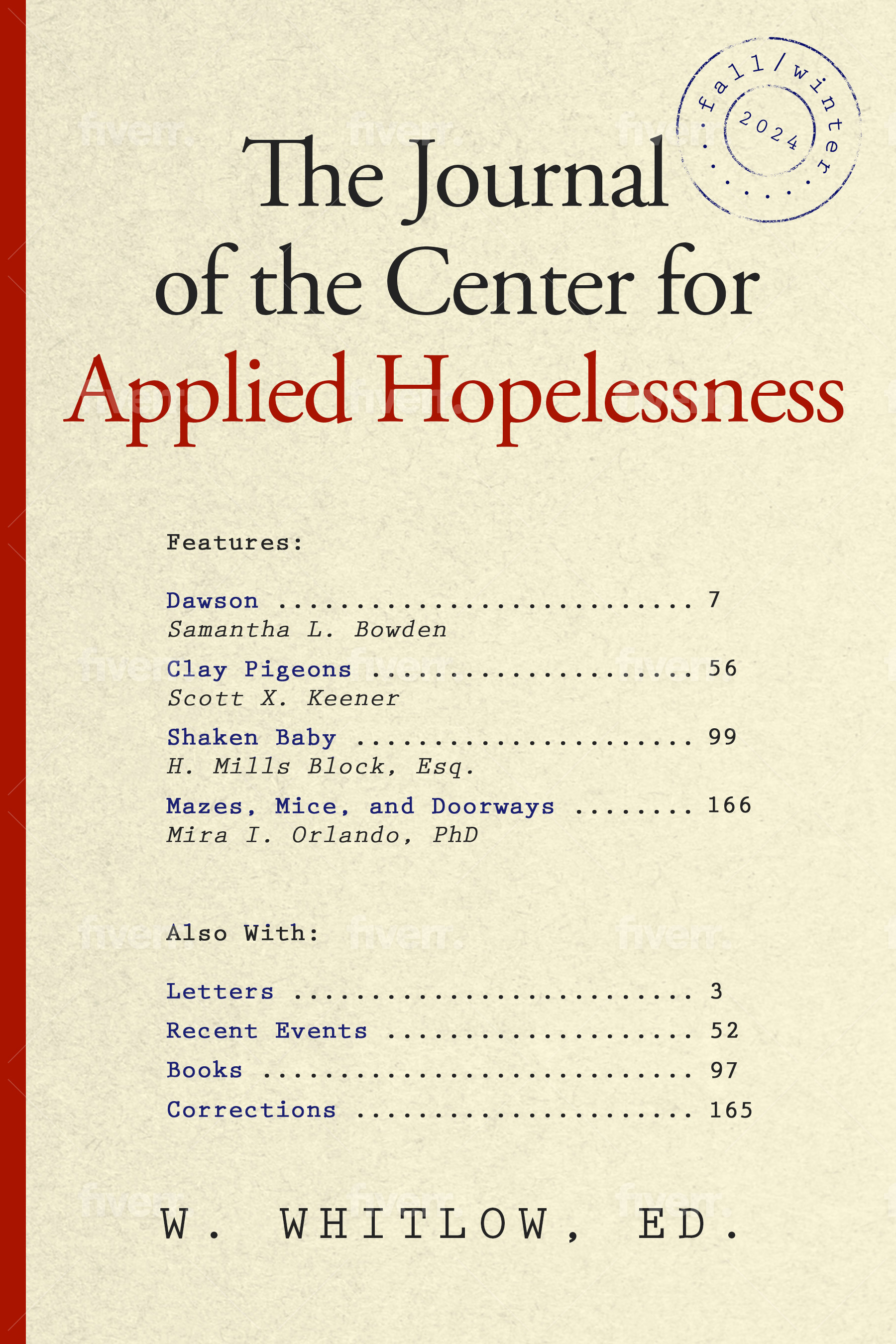

This edition includes an essay by Samantha Bowden on the death of her nephew, who took his own life five years ago this fall. In dying, she writes, he forced her to go on living, if only to carry the burden of his memory. Reeling from the poor sales of his debut record, Scott Keener dives into the meaning of failure—in art and in life. Lawyer Mills Block reflects on living with crippling social anxiety and his time spent representing Lionel Mering, a man wrongly convicted of the murder of his child. Mira Orlando provides us with an introduction to affective ontology, a discipline to which she has dedicated most of her life and which tries to make sense of the world we call depression. And, as usual, we have gathered here letters, corrections, recent events, and book capsules we think may be of interest—some of which dwell on topics dreary and others that might just distract us for a little while.

I will end the beginning by mentioning, if it isn’t already obvious, that when things are good, they’re good. When things are good, we don’t need stories in which to find solace. We don’t need these pages. So, I hope that this will be the last edition of the Journal I ever have to edit. I hope it, but like so much here at the Center for Applied Hopelessness, I won’t hope too hard.

Stay safe,

– Wilson

----------------

Letters

Dear Wilson,

It was with some not little annoyance that I read Matt Chester’s article “Canvas Spring” in the Fall/Winter 2023 edition of the Journal. What is all this about the “artist’s life”? Mr. Chester seems to want us to believe that playing hooky from work for three months so we can paint pictures is going to solve all our problems. What about the problem of paying rent? Putting food on the table? Paying for jazz camp for our kid? Will these “aesthetes” like Mr. Chester ever stop banging the drum about how art is the path to some perfect life? Most of us would feel a whole lot better if we didn’t have to worry about money all the time, let alone having three months “to ponder a drop of sunlight.” How about Mr. Chester tell us something that makes us feel better about the lives we have rather than crummy about the lives we don’t?

– Mary Baldwin, Morgantown, WV

Wilson!

Dude! I totally saw you on the jumbotron at the Nats vs. Brewers game last Friday, or I think it was you. Were you with an enormously tall woman wearing a yellow bonnet? I could have sworn it was you because you both looked bored as hell. Who was that woman? And were those homemade chicken sticks she was eating out of a Tupperware container? It wasn’t Grace, I can tell you that. Does your wife know that you have a baseball mistress? Are you really too cheap to buy her chicken fingers at the concession? And since when do you have a beard and wear horn-rimmed glasses? Anyway, seeing you up there on the big screen fanning yourself with a copy of Foreign Affairs while your lady friend sucked her fingers, I suddenly remembered that you still owe me from when I spotted you ten bucks to buy a leather bullwhip on that Gettysburg field trip in the fourth grade. My generosity may be infinite, but my patience isn’t. So pay up or I will tell Grace about your dalliance at the Nats game. I’m not bluffing, Whitlow.[1]

– Meg Francis, Silver Spring, MD

Mr. Whitlow,

Again with The Journal of the Center for Applied Hopelessness. Again with all the woe-is-me. I still can’t figure out how to cancel my lifetime subscription to your “esteemed periodical,” so I have taken to using each edition to prop up the corners of furniture in my house. Thanks to the Spring/Summer 2019 Journal, my TV dinner table no longer wobbles, and I can watch Shark Tank without worrying about losing my nachos supreme. How about this for a business idea? People pay a subscription, and every month instead of something new arriving in the mail, something disappears from their home—one less magazine to read, one less recipe to try, one less hockey game to watch, one less TV show to keep up with, one less obligation, one less complication. Eventually, after years of this, instead of our lives being cluttered with things we will never be able to do or see or read or understand, we are alone with each other. What would that be like? That white world after death where Harry Potter meets Dumbledore, where there is nothing but what we can remember? If I met Mark Cuban in that afterworld, what would we talk about? Would we agree that all the things that passed through our hands, all the movies we watched, all the words we read, all the games we cheered through, all those million days at work made our lives more real, or less? I’m asking these questions because I want an answer. So, what about it, Mr. Whitlow?[2]

– Finn Albert, Vancouver, BC

Hey Wilson,

Monday afternoon I got a pin for twenty-five years of federal service. The front office had warned me ahead of time, so I spent too much time that morning fussing over what I would wear and then loosened my tie just before the ceremony so it wouldn’t seem like I cared too much. The boss pinned the device on my lapel and gave it a playful pat. “Next stop, thirty years,” she said, and it was like a trapdoor opened underneath me. But instead of falling in, I just stood there over empty space. When I got back to my desk, I took the pin off and put it in my desk drawer in a cup where I keep loose change. I hung my jacket on the back of my chair. I settled in behind my computer and logged on. The door to my office was open, as usual, and looking out, I couldn’t see anyone but could hear typing and the sound of voices behind cubical walls. Someone laughed sharply and then stopped. I looked at my calendar and remembered that I had a 4 p.m. meeting. I drew an airplane on a yellow stickie and threw the stickie away. I read a news article about interest rates going up. And like that, I’ve just been staring at details. Maybe it’s because I don’t want to see the big picture. Or closer to the truth, Wilson, I don’t think I can.

– Freddy Best, Clovis, CA

Dear Mr. Whitlow,

I know my father spoke to you about “Dawson,” and I know that you are going to print it anyway. I talked to him. I asked, isn’t it better to remember what happened than not at all, even if it’s not the way he wants to remember it? But I don’t think he wants to remember. You have to realize that all the joy went from his life the day Dawson died. It’s just a mess, we’re all a mess, and none of us knows what to do about it. Anyway, can you do me a favor? Can you let your readers know what I’ve already told my Aunt Samantha? Can you let them know that I love her, I understand, and I am not mad? I want people to know that. Thanks.

– Lilian “Cohn,” New York, NY

[1] Although that was not me at the Nationals game with an unusually large woman in a yellow bonnet, I have posted a belated sawbuck to one Ms. Meg Francis. As for the bullwhip, I lost it on the bus on the way home from Gettysburg. I looked and looked and couldn’t find it. I remember feeling like I had lost a limb, I was so upset. It still makes me sad to recall that lonely bullwhip misplaced somewhere in the tenth year of my life. – Ed.

[2] Sorry, no clue. – Ed.

----------------

Dawson

Samantha L. Bowden

Author’s Note: We live in an age of promiscuous judgment. It’s just too easy to read snippets about other people’s lives and decide you would have done things differently or better. Outrage flies over all details and lands directly on condemnation. If you are one of these people, I invite you to judge me and not my sister, her husband, or my parents. Judge me, the one who wrote this against their wishes and, while having changed names, cannot protect them from what they view as a betrayal of their privacy and the exposure of their greatest trauma and deepest shame. But judge wisely. By telling all of this, have I done more good than harm? Have I honored Dawson’s memory or simply exploited it? What kind of person, after all, fails in the ways I have failed and tells the world about it? I don’t know, but it seems to me that that is the question that underlies all of this, the question, beyond all, that might have saved Dawson’s life.

I

Dawson was sixteen years old when he jumped from the roof of the Gelb Science Center at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. He fell fifty feet and landed on the asphalt lot behind the building just off Highland Road. He was found by a faculty member at about 9:30 a.m. on Saturday, November 30, 2019, and pronounced dead two days later.

Had my sister Kara and her husband, Jonathan, printed an obituary or held a public funeral, they might have noted that Dawson was survived by his parents, his sister Lilian, paternal grandparents Stuart and Rachel, maternal grandparents Fred and Kim, and, as it goes, loving aunts and uncles, cousins and friends, and me: the only sister of his mother, that stringy brunette you might have seen standing uncomfortably along the sidelines of some family event, sneaking out to smoke, drinking too much, maybe, or maybe saying the wrong thing before her dramatic departure. The aunt who never really liked, spoke to, or thought much of Dawson Cohn until that morning he went and redrew the map of her world.

II

Dad thought Mom was beautiful. He said so. I have this picture of them from when they were young. She’s sitting at the kitchen table in my grandma’s house smoking a cigarette. He’s got his arm draped over the back of her chair and he’s looking at her like I’ve seen in photos of Hugh Hefner looking at one of his wives. Pride of possession, but not much actual interest. Another photo. She’s talking to my Aunt Mary. He’s not listening. He’s looking at someone out of frame and smirking. I’ve seen that look a thousand times. In Dad’s book, Mom didn’t have much to say. He would let her talk and talk, occasionally cutting her off to correct her. She would smile and wag her head like she agreed completely and go back to what she was saying. It was never clear what she actually thought about anything, and I don’t think it mattered to anyone. She was always there, though, a hovering, helpful monologue. If you needed anything, she would get it for you somehow. If you needed to be seen, she would see something, though maybe not what you were trying to show her. If you needed to see her, she would disappear behind a veil of recipes, book recommendations, cleaning tips, great buys, talk show gossip, and family drama that always seemed to involve someone other than us. An ever-running river of talking. And when Mom went into her room alone, it was like she vanished completely. I couldn’t imagine as a kid—and I still can’t imagine—what she was, or is, to herself.

Another photo. This time the kind with the scalloped edges and fabricky texture, the date burned into the corner in fuzzy yellow letters: April 11, 1982. Easter morning. Plastic eggs dangle from the dogwood in front of our house in Maryland. I am three, Kara’s six, and Mom’s got us in matching dresses of peach taffeta and white buckled shoes. Dad’s wearing a gray three-piece suit and he’s kneeling with his arms around Kara and me. His smile is genuine, albeit a little too eager, as if he were showing two purebred poodles to the judges at Westminster. If you look closely, you can see that he’s put a dish towel under his knee so he won’t spoil a pant leg in the dewy grass.

Last photo. All four of us now. Mom is wearing a lavender dress with shoulder pads and a slim waist gathered by a white belt. Dad’s got his hand on the small of her back. Kara and I are in front holding up colorful wicker baskets overflowing with pink plastic grass and goodies. Our faces are painted with squinty smiles in the morning light. I seem to remember—or maybe I’m filling in—Mom flitting back and forth between us, fussing with our hair and smoothing our dresses while Dad set the timer on the camera importantly. These were the days before you could just take a hundred pictures and pick the best one. We had to look just right. They worked hard to make things just right. You see, my parents operated within the parameters of a middle-class family living comfortably within their means. Neither had ambitions to break the bank. Neither cheated on the other, at least not that I’m aware of. They fought, but not terribly. He worked. She kept house, shopped, and chauffeured. They raised two daughters and kept a clean home. The grass was always cut. The shrubs were never unruly. They were not physically abusive. They rarely even raised their voices. We were never cold or hungry or frightened in our own home. They could not be blamed for anything specific: they kept up their end of the American bargain.

Yet, looking at this scene so many years later—the stone chimney, the front windows reflecting the houses opposite, the daffodils standing out against the wet mulch, the egg tree, Mom and Dad, Kara and me in our matching peach dresses—this family of four (no more, no less) seems to me ominous, like the prelude to a horror film or one of those true crime dramas where the narrator suggests a picture-perfect family only to draw back the curtain on the rot within.

III

Skip forward twenty years. New York City, 2002. A May wedding at the Temple Emanu-El. A procession of horse-drawn carriages clattered down Fifth Avenue to the Plaza Hotel. At the front were Kara and Jonathan being pulled by a pair of chestnut horses decked out with bells and ribbons. In the next carriage rode Mom and Dad and Jonathan’s parents, Stuart and Rachel. I was in the third carriage, the first of five for the wedding party and special guests. The day was blessed, so said the rabbi, and the afternoon light shone through the leaves of Central Park, all green and gold. Looking over my shoulder, I saw my parents bouncing along, Mom vacantly beaming in the way she does when she’s out of her element and Dad staring up at the pristine stone buildings, jaw slack with ravenous awe.

Dad was raised Christian, but his true religion was Progress. In ’48, he told us, when his parents got married, they walked down the street to the fire hall where his Uncle Ted spun records and Aunt Maude served drinks. Their honeymoon was two nights in a cabin at the edge of my great-grandpa’s farm. In ’75, when Dad and Mom got married, they had the reception in the big room at the Radisson. The newlyweds spent a week on the Jersey Shore. By the turn of the century, the compounding interest of generations of modest pleasures had hit pay dirt, here, in Central Park South, in the Grand Ballroom at the Plaza Hotel, where Dad stood up, a little tipsy, a little teary, and raised a glass to Jonathan and Kara Cohn. “I don’t think I’ve ever been happier,” he said. I have no doubt that it was true, but it was not the glory of love that filled him with joy.

Dad’s devotion to Kara and me had always been a little precious, a little clichéd. He called us his “princesses” far longer than should be allowed. But that’s what he wanted us to be: Disney princesses. Brave, dutiful, selfless, and above all unconsciously gorgeous, like all of those wasp-waisted cartoon beauties. I think he thought that if he projected that fantasy onto us with all his might, we would pass through adolescence untouched by beer, saliva, and semen, and when we got to adulthood, he would give us away, pass us off at an elaborate ceremony that would celebrate our nuptials as much as his acumen as a provider. It’s not clear whether he ever viewed any of this with any sort of irony or philosophical remove. Yeah, he joked around with his work buddies about the expense of keeping up with all the hormonal demands of three women, but I don’t think he ever questioned his purpose for a second.

He wanted to be a respectable man. That was the thing. He wanted to hold up his end of a conversation or a bargain, to be a breadwinner, to keep his chin high in front of all the world. And that evening at the Plaza, Dad’s joy was like that of a scientist whose grand theory, after many years, had been proven true. The dream worked. And from the top of the hill, he could look down at the road behind him and know that he had been right all along. “This is the beginning,” he said, his eyes wet with tears, “of good things to come.”

I looked over at Kara. She was crying too. So was Mom. But whatever joy or triumph or nostalgia they were feeling was not what I was feeling. It was not for me. For in our world, they were always inside of a kind of secret circle, and on the outside, there was me. And the price of admission among them was to become something I was not and could never be.

Comments

Interesting!

This is an interesting premise and a great start. Very well-written!

I was intrigued right from…

I was intrigued right from the logline "fictional journal of the social sciences dedicated to the exploration of hopelessness in its many forms". You have done a great job with infusing humor in the writing. The tone feels relatable and quite friendly. Keep it up!