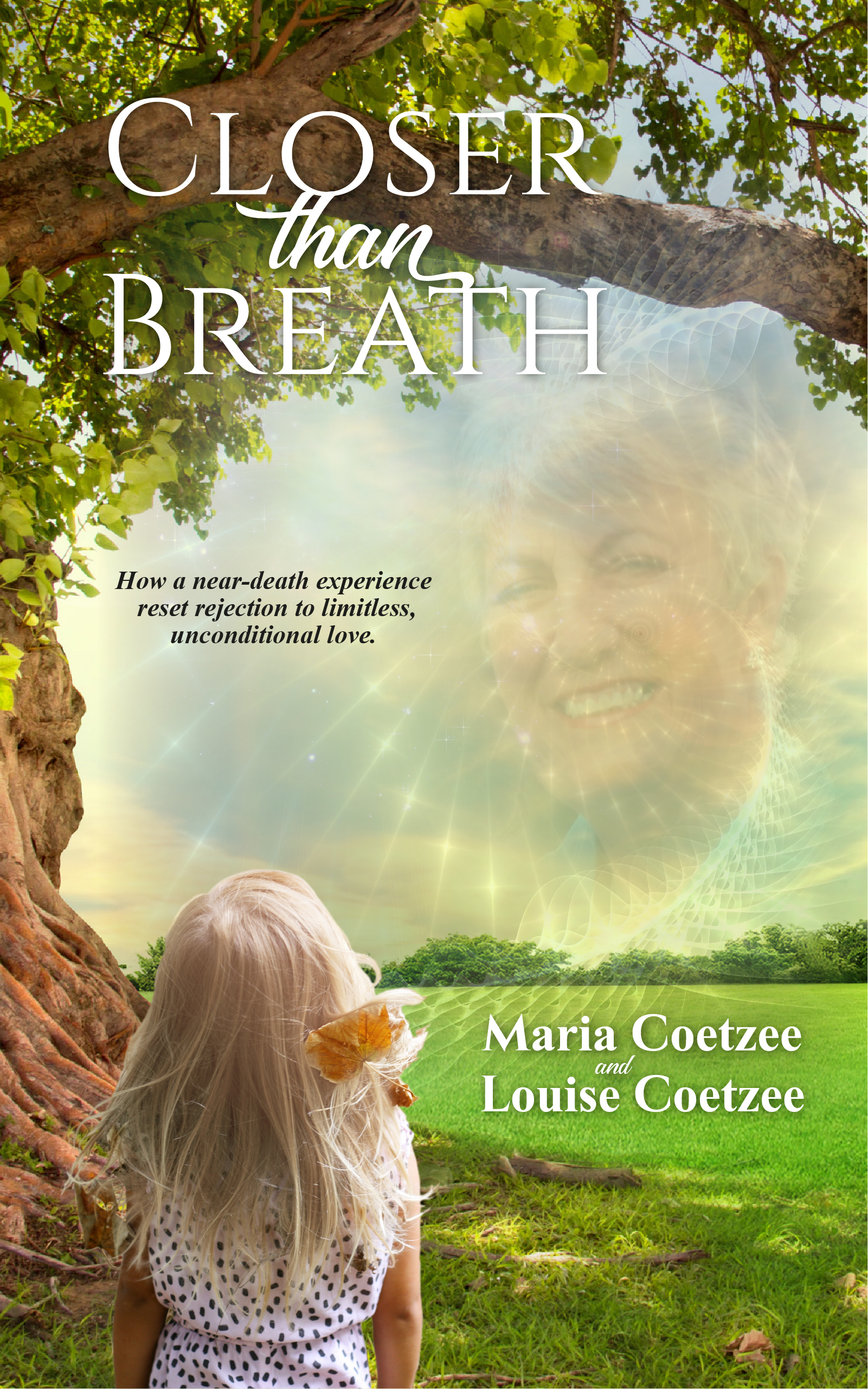

Closer than Breath - How a near-death experience reset rejection to limitless, unconditional love.

When a woman’s near-death experience results in her meeting Jesus, it contradicts her beliefs about God, the afterlife, and life on Earth. The encounter changes her forever and brings with it an unexpected surprise.

Prologue

This must be it. This is how I die.

I stood on the slope of the valley my husband and I were clearing for a dam. In slow motion, the next few seconds played in my mind’s eye like a movie. The tree jerked to life as the tractor pulled it downhill. It rolled over and, as if alive, speared a defiant root into the ground. The rest of the tree became airborne, swung like a crane and whiplashed in my direction. Surely what I thought I saw was not happening? I turned to look back.

My heart sank.

Time ground to an agonising crawl.

My insides churned in denial.

It lasted only seconds, but those moments before the tree hit me were enough to initiate a tangle of prayers, hope, and denial, despite the quiet awareness deep inside that the moment of impact was speeding towards me. I could do nothing—that was the only sure thing—yet I hoped for a miracle. I had no idea of the effect it would have on me, my family, my life, the future—everything I knew to be real. I had always expected to meet Jesus when I died, but not like this. Nothing I had heard or read or learned about Jesus in my 58 years could have prepared me for this moment.

What followed was the discovery of a spiritual world so incredible it is impossible to capture in words.

As the tree swung towards me, I was overwhelmed by an urge to run. Since it had rained in the few days prior, the area was muddy and uneven. Fallen trees, waiting to be cleared, lay scattered, and the rough terrain made it difficult to escape. My legs could not fight the mud and holes to trek uphill out of the way. It was too late.

This is it then—a tree of all things.

1

The Worm Plan

I nestled closer into the branch’s safety, my arms barely reaching halfway around its magnificence, my head low, huddled into my body. The armoured crust scraped my knees and arms, leaving tiny pink tracks, but I did not mind. The branches swayed gently, and the leaves hushed the voice of my mother. Our home in South Africa in 1965 had a larger than usual yard for the small town we lived in, which meant many hiding places for a six-year-old, but this was my favourite spot.

‘Miemie!’ She could not find me or see me here. My stomach tightened. I held my breath and kept quiet. Mum stood close to my tree, apron in hand, one arm on her hip, and muttered.

She will give up soon and go back inside, I told myself. I just needed to be patient. She called my name again, followed by a sharp tongue click. With a quick turn of her heels, she walked towards the back door and flicked her apron; the bounce of her dark locks reiterated her disdain. She knew where I was and that I could see her. That flick was her way of letting me know that she had not given up—not after what I had done.

I stretched my legs out on the branch and breathed out. A giggle burst from my lips, but my fingers failed to smother the sounds. I smiled. The stunt replayed in my mind. This one made the top of my clever ideas’ list! It topped hiding grasshoppers in my sister’s toiletries bag, sand in her toothpaste, or spiders in her drawer. It was even better than the old bicycle tube in her bed. I would find the most vulgar-looking earthworms, the length of small snakes, and chase my sister, threatening to throw them down her back. She would run away, hysterical. Although my sister was nine years my senior, I believed I was in charge. I was the youngest of five; my three older brothers already married and starting their own lives.

That day, while my sister sat at the kitchen table, I’d concocted an ingenious idea. I picked a sage leaf from Mum’s garden, rolled it tight between my fingers, then sneaked up behind her and dropped it down her back. It unrolled against her skin, and I knew its hairy texture would feel like a worm. I expected to be rewarded with terrifying screams. Instead, my sister sat there speechless and in shock. She barely breathed, and the horror on her face indicated she would not recover soon. I did not feel regret or shame, but fled the scene laughing, pleased my evil idea had worked.

Eventually, I climbed out of the tree and faced my mother. When I did, she gave me a decent hiding, one of many, resulting in zero behaviour change or compliance. Every time I hid in my sister’s wardrobe with a pillowcase over my head, or grabbed her ankles from underneath her bed, or snuck up behind her while she hesitantly opened the wardrobe door, expecting me inside, she rewarded me with screams. Every single time, I fell to the floor, hysterical with laughter. And without fail, my mother would give me a hiding. I refused to cry, refused to provide her with the satisfaction of seeing me in pain. I would hide somewhere no one could see me, usually in my tree or on the roof, and cry. This happened daily, sometimes multiple times a day.

In a desperate attempt to try something different, my parents told me the story of an eerie hermit who lived in the mountains and never came into town. Apparently, he wore skins for clothes and ate naughty little children. They threatened to drop me off in the mountains if I did not stop teasing my sister.

‘Oh, he won’t eat me.’ I shrugged my shoulders. I knew they would not let the scary man take me. ‘You could drop me off at the poor hermit’s place anytime. He is probably just lonely and would love my company.’ A triumphant grin crept over my face as my parents’ only response was a head shake followed by silence. I realised they were bluffing. The hermit was make-believe.

Today, I despise worms—any worms. There are no good-looking or cute ones. The mere sight of their little wriggling bodies sends shivers down my spine. They embody everything that produces feelings of horror. My kids snicker when I tell them that I teased my sister with worms when we were children. They tell me my fear of worms is my punishment for teasing.

If you asked me why I teased my sister with such relentlessness, I would probably not be able to answer. Even today, I wonder if it was because I wanted attention or if I was jealous of how perfect she was. My sister was any parent’s dream child—courteous, reliable, and disciplined. To add to her impeccable behaviour was her gorgeous dark hair, large brown eyes, and dimples when she smiled. It was easy to boss her around as she was soft-spoken and tender-hearted.

Nothing my parents attempted could change my behaviour. Not until that day with the sage leaf.

Dad returned from work as the trees’ shadows stretched thin and tall across the yard. After the hiding from Mum, I hid in my tree again and later watched while Dad walked into the house. The smell of dinner and Mum’s high-pitched voice drifted from the house. Moments later, Dad filled the door frame.

‘Miemie.’ His voice was deep, and my name sounded like an unpleasant word.

‘I’m coming!’ I hastened down and scraped my elbow, but didn’t notice until later. My painful backside, from the strap earlier, was far from my mind when Dad said I should sit on his knee. Sitting on Dad’s knee when I did something wrong was worse than the strap. Tears stung the corners of my eyes. I pinched my lips together and refused to cry. He would not know how vulnerable I felt. I could not run or hide. This was just another telling-off episode, I told myself.

‘Why do you tease my daughter so?’ he asked. ‘We have only been good to you. Your parents did not have the means to take care of you, so we took you in. We felt sorry for you, and in return, this is how you treat our daughter?’

Our daughter.

The words punctuated my mind. My sister was their daughter—their perfect daughter. I was not. She looked like my mum. I did not. I was not theirs. Not their daughter.

I stared at the photo frame at the far end of the room. It was decorated with two timber doves and held black and white photos of Mum and Dad when they were babies. Two pictures were placed together in a single frame, two who became one.

The kitchen clock’s rhythmic tick-tock penetrated the walls and the furniture—brassy and triumphant—and filled my ears, my throat, and my tummy until it was the only sound in the world.

This is just another scolding, right? I told myself, but it felt different from the hermit story, different from the spankings and usual telling off.

Everything that once seemed solid became blurry as I tried to focus through the welled-up tears. My insides felt like hot melted wax. I was determined to conceal the turmoil inside. I swallowed hard and tried to keep my face expressionless.

‘Where am I from? Where are my parents from?’ I tried to control my voice, sound monotone, but the words felt shaky. If this was real, I would know. I would ask my questions and get my answers.

‘Potchefstroom.’ He answered frankly. The name lingered above my head and gradually faded. I felt compelled to fill the silence.

‘May I meet them—my real parents?’ My chin quivered as I spoke the words which felt foreign on my tongue.

‘It is against the law. When someone is adopted, the register is sealed.’ He pressed his lips together for a moment. ‘It is for their own protection.’

The last rays of sunlight tickled the dust specks around us as dusk seeped through the curtains. In a few seconds, all the colours drained from the room.

Was this just a nightmare I would wake from soon? A trick of the mind? Something that could happen to someone else while I watched from afar?

Only later that night, as I pulled my blankets tight under my chin and hid in the familiar darkness of my room, did my mind form the words I never thought I would; replayed them like an echo that would not settle—over and over and over.

I was adopted.

The sun rose again the following morning. The pigeons sat on the telephone wires and cooed as usual. Did they not hear my news? My morning routine spilled into Mum’s garden. Tiger, my scrawny kitten, purred and bunted against my back, its fur a dull ginger, like the colour of a washed-out dress that used to be a favourite. I picked it up and sat it on my lap, ran my fingers through its soft coat. I thought back to the day I pulled it from the stormwater pipe, half-drowned. Its coat looked more like something had chewed it and decided to spit it out. It yowled and clawed onto my arm, desperate to escape the water. Flea-invested and with bewildered eyes, she smelled musky—the kind of smell that lingers in your nostrils longer than it should. I did not care the day I rescued her, and I still did not care. I hugged her close to my face; my heart again overwhelmed by her helplessness and vulnerability. With my heart in my throat, I cuddled Tiger into my neck. My tears left a wet patch on her coat.

The air pushed against my skin, fanned my blonde hair into a golden dancing skirt, and disturbed the dust. A few seconds later, the wind abandoned Tiger and me. The dust swirl settled around us. My beloved tree swayed and beckoned with its arms open, waiting. I was not so sure if the tree was mine any longer.

The truth hung like lead sinkers from the bottom of my heart. My dad, my mum—they were not mine. I was not theirs. I felt conscious of the space I was occupying, like I had to be careful not to take up too much, just enough to breathe.

I heard footsteps and looked up. My sister walked towards the vegetable garden, picked a tomato, placed it in the rattan basket, and then smiled at me. I looked away to avoid eye contact. How was I meant to look at her now? She was not my real sister. Who was she to me then? Maybe she was just loaned—a loaned sister.

Despite my age, I did not overlook the perplexing idea that grace was extended to me, that it landed in my lap, and that I was obligated to treasure it. Because I was not their daughter, and my sister was, I pulled my head in and stopped the teasing. How could I not? I dared not toy with the grace that now seemed so fragile. On multiple occasions, my parents have told me how discouraged they were. My mind imagined what the most likely next step would be, and a chill ran down my spine. What if they got so discouraged that they would take me back to the orphanage? What if they did not want me anymore?

On the other hand, I despised the idea of being pitied. We felt sorry for you. I did not want to be ‘felt sorry’ for. I did not want to be the lost kitten rescued from the stormwater drain. I did not want pity; neither did I want to be vulnerable. For the first time, I noticed the strange feeling of the day’s colour. There was something different, but I could not pinpoint it—like something had shifted.

My world had changed, thanks to a worm.

2

The Fury of Water

‘Wow, Dad, that must have been so funny to see. What else did Oupa do?’

At age nine, I loved to ask my dad about his childhood. He would relay the curious events full of vigour, and when he chuckled, it was a low hum that bounced like a swift-footed deer brushing the floor of our garage ever so slightly before disappearing into the peachy afternoon. I would tilt my head back and laugh from my belly, unreserved, letting our laughter’s melody flow over me like honey.

‘I’ll tell you about the time he broke in a couple of horses, but first pass me that spanner, please.’

I passed the tool on and Dad adjusted something on the tractor. I listened with intent and watched as the words bubbled over his lips, somewhere from deep inside a well of kindness and strength.

‘Miemie, you’re doing such a great job.’ He held my gaze for a second. ‘I’m proud of you.’