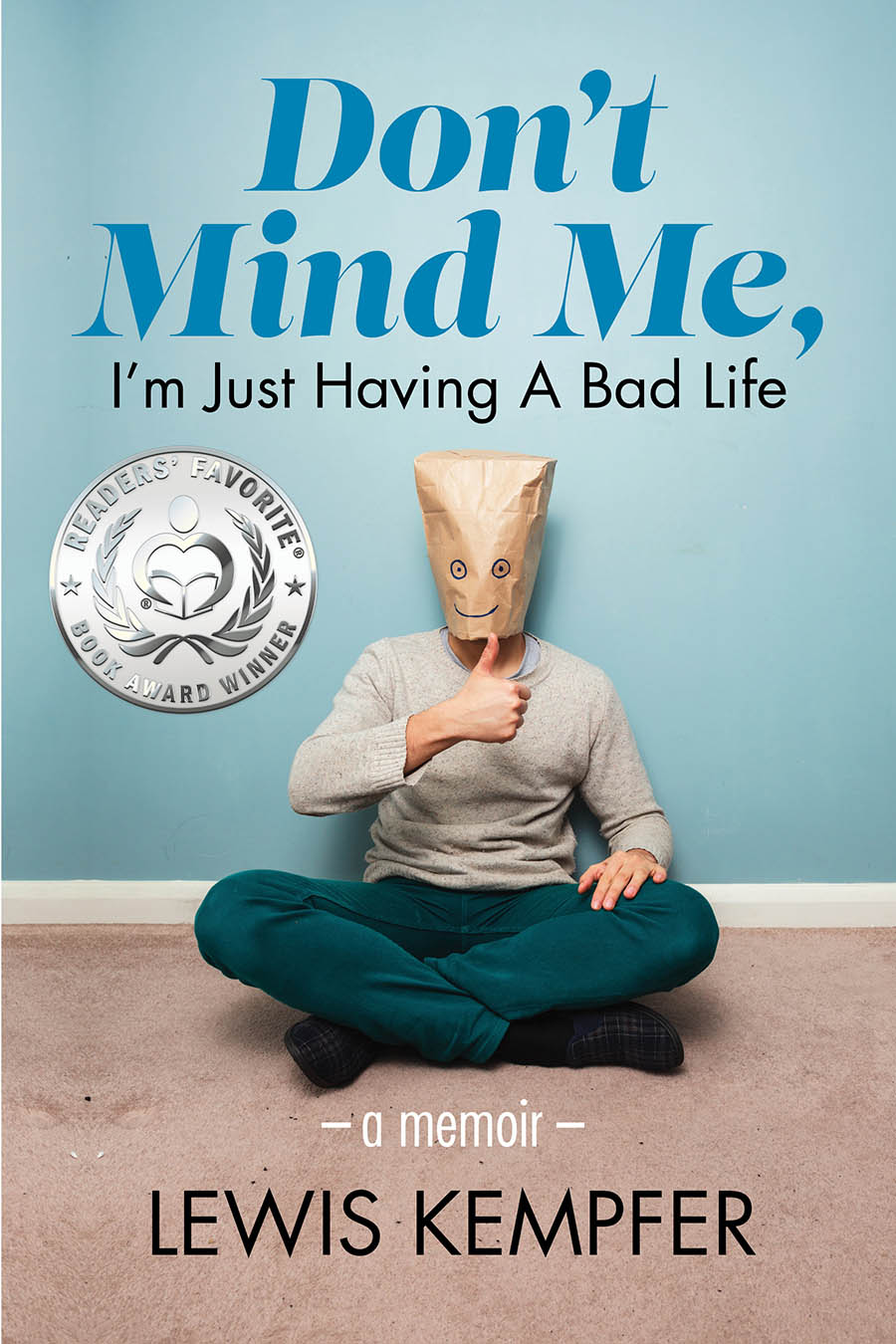

Don't Mind Me, I'm Just Having a Bad Life: A Memoir

Prelude

Death Wish

Hollywood, California: 2008

Spinning out of control.

My head was spinning, and my stomach was churning, doing somersaults between violent bouts of vomiting.

Dying.

Was this how dying felt?

My limbs were heavy, too heavy to move. I couldn’t hold my head up. I couldn’t focus my eyes. I was sure I was going crazy. Or dying. Probably, maybe, hopefully both.

Was that a demon that just popped out from behind the drapes? And what was the creature that just disappeared into the closet?

No, I didn’t want to die—at least not this way. Naked, except for the leather restraints on my wrists and ankles, I found myself sliding around in my own bodily fluids on the filthy floor of an infamous gay drug motel in east Hollywood.

I had been throwing up for what felt like hours since I dragged myself from the nasty, flea-ridden mattress to the toilet.

No, I hadn’t been kidnapped. I had rented the motel room. I had bought the drugs. And from my ad on Craigslist, I had carefully selected and hired a mean-looking, tattooed Mexican gangbanger to tie me down and rough me up. In our online chat, I pushed for a name only because the front desk would require one. He said his name was Miguel. I didn’t care.

My arms were already bruised and bloody from my own attempts to slam before he arrived at my motel room and made it worse with his multiple stabbing attempts of finding a decent vein.

Once I was sufficiently high, he clicked the padlocks on the restraints and made me drink a tall glass of Diet Coke mixed with GHB. The “G” was to facilitate the scene I had devised: knock me out, and bring your buddies over to use me, rape me, kick my head in, whatever. I didn’t care.

I don’t think the scene unfolded the way I had scripted. Apparently, the dose of GHB was near lethal, and he told me he’d shot me up with more meth in an attempt to revive me. He said he didn’t want to be stuck with a dead fag. So, once I was awake, he unlocked the restraints and was gone.

Usually, I hooked up to feel wanted, attractive, special, or for some measure of validation. This time, I wanted to be higher than I’d ever been and severely beaten. This time, I wanted to punish myself for every mistake I’d ever made in my life, including becoming addicted to anonymous sex and crystal meth. I wanted to show the world how much I hated myself. This time, I thought I had a death wish.

But there, on my knees, naked, drugged nearly to death, and helplessly alone, I called upon the God I’d never known and had always pushed away.

I prayed, “Dear God, dear Jesus, dear whoever’s up there, please don’t let me die this way. Not here. Not today. Please.”

As I slipped in and out of consciousness, I was certain a flock of demons were crowding around me.

Then I blacked out.

1

Worthless Kid

Aurora, Colorado: 1970

I have a dirty secret. Not a little secret, but a huge elephant-in-the-room secret. This secret has been far more debilitating than if I had gone through life missing a limb, or an eye, or my hearing. I hate myself. I believe I’ve always hated myself. This deficit of self-love has been the force that has propelled me into countless traumatic situations and negative experiences.

But just how and when did it begin?

I was four years old when I moved to Colorado with my parents. It was the second of two big moves; this time from Omaha, Nebraska, due to my biological father’s job as an engineer at Western Electric. I never knew exactly what he did for work, but I figured it had something to do with trains.

We lived in Aurora in a small apartment while our new house was being built. Mom called it a ranch, and I incorrectly imagined a place with cowboys and horses. Turns out she meant ranch-style house, the one-level flavor.

Every weekend, my father would pile Mom and me into the new 1970 turquoise Chevrolet Nova and make a sort of weekly pilgrimage to the construction site. It was at the bottom of a steep cul-de-sac called Chambers Road Circle, and it felt like an amusement park ride when the car went down the hill. It made something deep inside my stomach sort of tickle, like the time I went on the Tilt-a-Whirl. He would march us over uneven dirt mounds and around piles of lumber scraps, as he inspected each nail and screw, every pipe and board, making sure he got every cent of value out of the seventeen grand he’d paid Melody Homes.

One day the ranch was finished. In it I had my own room with a twin bed and a scratchy, orange and brown plaid bedspread. On the yellow wall next to my bed, Mom hung a set of cardboard cutouts of dozens of Disney characters. I loved looking at them because they looked exactly like their pictures in my Disney books. But Mary Poppins was my favorite because she made me feel safe. Despite her ability to fly, she was the cutout whose Scotch-tape attachment often failed under the added weight of her umbrella and carpet bag. Frequently, in the middle of the night, she’d come sliding and scraping down the wall.

Nice move, Poppins. You were supposed to be my protector, but instead, you scared the crap out of me.

Mike Leak lived in the house to our right. He was the cool kid, the one who made catching a football look easy, the one who was always in charge. He had a dog and a sister and the biggest Big Wheel bike, the likes of which I had only ever seen in the Sears Christmas catalog. I adored him. As an only child, I wished I had a brother like Mike. He lived uphill by one address, and there was a great grassy slope between us that served as the stage for many afternoon adventures. Often, our mothers would pin bath towels to our shirts, and we’d run up and down the hill as superheroes. I was always Robin to his Batman; it was, perhaps, the first layer of my less-than foundation. He was always the boss and always the one who decided when, where, and what we would play.

On hot afternoons, he wanted to run through the sprinkler in my backyard. Sometimes he would bring his Slip ’N Slide. My contribution was a toy called the Water Wiggle. Basically, it was a yellow, phallus-shaped mushroom cup head with a stupid face and a sprout of black yarn for hair. When hooked to the hose, the Water Wiggle would jump, spin, and cavort uncontrollably, thoroughly soaking everything within one-hundred feet. Mom hated the thing because it would spray her freshly Windexed windows. My father had been in the Air Force and expected his home to be spotless, going so far as wearing a white glove from his military uniform when he checked for dust. Mom worked hard to please him. She always tried to make everyone happy.

And I liked making Mike happy. I also liked touching Mike—nothing sexual, of course. I was only four going on five and had no idea what the thing between my legs—that thing Mom called a “dinglebottle”—was used for other than making pee-pee. But I liked to touch Mike on his arm or on his shoulder. When I would try to hug him, he’d push me away saying something like, “You’re gross.”

Then, one day, I was no longer allowed to play with Mike. His big bull of a father had made it clear to my father—who, from this point forward, I will only refer to as Dennis—that I was no longer allowed to play with Mike. (At that point in my life, I was the junior to my father’s senior and was called Denny instead.) Dennis yelled at me because Mike’s dad had yelled at him. I didn’t know what I had done wrong, but Dennis told me I was punished and had to stay in my bedroom with the door closed. I wasn’t allowed to look at my books or play with any toys. I was to sit quietly and think about what I had done to make Mike’s dad so angry.

I tried to obey, to be still, but my eyes were hot and wet, and I felt like I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t know what had happened, but it must have been very bad, and I screamed and cried because I could no longer be Mike’s friend. I was so mad at myself that I beat my forehead against my wooden headboard. It must have helped because I stopped crying and just sat on the bed, hanging my head. Dennis called that behavior pouting, something a spoiled-rotten kid did when he didn’t get his way. But it wasn’t that at all. It was just a hollow, empty feeling. It may have been my first experience with depression.

But is it even possible to be depressed when you’re only four years old? Perhaps. The feeling didn’t have a name, at least not any that I knew. Rather, it just felt like a gloomy, rainy day despite the hot Colorado sun overhead. It wasn’t the sad feeling; no, sad felt and tasted differently. Sad was its own thing.

And when I felt this way, nothing could make me smile. Not a new toy, or a new book, or a new record. Mom would try to get me to play a game with her or listen to her tell a story, but I just wanted to be alone. I just wanted to hide under my bed where I felt safe. There, behind the scratchy bedspread that hung all the way to the mustard-colored carpet; there, with my Geronimo action figure; there, I felt somewhat safe. Maybe safe isn’t even the correct word, but rather, out of sight, especially if Dennis was home. Because if he couldn’t find me, he couldn’t yell at me, and if he couldn’t yell at me, he couldn’t hit me in the face like he did when I spilled a little cup of strawberry shake from McDonald’s in the back seat of the new car.

I felt safe when I was with Mike. He was slightly older and slightly taller and was good at everything. But now that was over. Sure, there were other kids on the cul-de-sac. There was Bossy Deborah next door, who, unprovoked, had hit me in the head with a stick. There was the older, supposedly retarded son of the German couple across from my house who would spin in circles on his front lawn. And there was Mindy and Her Pew, a bizarre kid who always carried a wad of tin foil with something stinky wrapped inside. She called it her “pew” and protected the thing like an injured baby bird. The pickings were slim on the cul-de-sac.

Many nights, I would lie in bed crying softly, bemoaning my existence.

Why does everyone hate me? What did I do? What’s wrong with me?

That was around the time the little voice in my head made its debut, providing answers, “Because you’re different from real boys. You can’t catch a ball. You still ride a tricycle. You’d rather do girl things, like look at your stupid books when you should be playing outside.”

The little voice never had anything nice to say. Over the years, the voice took on different characters. When I first tried to locate the voice, I imagined the little devil and little angel who appeared over each of Fred Flintstone’s shoulders, always whispering conflicting advice.

Then, on a rerun of The Mickey Mouse Club, Jiminy Cricket would sing, “and always let your conscience be your guide.” I asked Mom who or what the conscience was, and she tried to explain that it was the part of me that told me whether something was good or bad.

Sometimes the voice sounded like Dennis. Later, it was a gym teacher or a psychiatrist or ex-boyfriend. But the messaging never wavered from its steady stream of condemnation.

The little voice was an asshole.

On Saturday nights, Dennis and Mom entertained some of his friends from work. They would come over to play cards or Monopoly and partake in the weekly quota of Pepsi. Dennis didn’t drink liquor and wouldn’t tolerate others drinking in his presence. Even soft drinks were something to approach cautiously; he would allow Mom only a half-bottle of Pepsi per week and only on Saturday nights. It’s not that soft drinks were necessarily evil, it’s that they cost precious pennies. The rest of the week it was water or watered-down Kool-Aid. Dennis was proud of his pennies and had a big, glass Miracle Whip jar filled with them that he kept on the kitchen counter.

I was afraid of Dennis and dreaded being alone with him. But I felt safe when he had his work friends over. Like George. George was the husband of one of the married couples who came over every week. George was easy-going, soft spoken, and friendly with immensely kind eyes. He was never upset or angry like Dennis. He would call me over while the grown-ups sat in the living room, drinking black coffee and talking about boring things. George would invite me into his lap and tousle my hair, as he pressed Brach’s butterscotch candies into my hand.

I wished George were my father. I couldn’t imagine him ever being mad and breaking things. I wanted to sneak away with George and his wife one night when they were putting on their coats and collecting their Monopoly game.

Maybe no one would even notice or care I was gone.

Dennis was always mad, always yelling, and it seemed to get worse after we were in the new house. He was a strict taskmaster with a relentless drive for perfection that frequently manifested as an angry and destructive temper. I didn’t understand at the time what it meant when Mom said he would “lose his temper.” I just knew that it rhymed with our last name and that he threw things whenever he couldn’t find “his temper.”

A Wisconsin native, Dennis loved his Green Bay Packers with a dangerous passion. When the Packers were playing, Mom and I knew to never disturb him. If they were winning, well, things were good. But when they were losing, as they frequently were in 1970, well, Hell hath no fury like a man whose football team was trailing at half-time.

It was after one of those games when Dennis couldn’t find his temper. Mom was sitting quietly on our fuzzy, chocolate-brown plank of a sofa making yarn daisies for her never-to-be finished, field-of-daisies afghan. I was playing on the floor with my Matchbox cars. The Packers had just lost. (It was their final game of a disappointing 6-and-8 season.) Dennis, who had been sitting on the edge of his seat in the orange swivel chair, leapt to his feet, picked up the spindly-legged coffee table, and hurled it across the living room, nearly knocking out the picture window. The coffee table landed noisily in a broken heap as it seemed to ask, “Now what did I do to deserve this?” Mom knew better than to gasp in astonishment and kept me still and silent. I think she was afraid we could be next.

I never understood how a little kid like me could make Dennis so angry. It just seemed I could never do anything to please him. My toys were never straight enough on my shelf, or I would forget to put my tennis shoes at the end of my bed. I loved my collection of books, but sometimes, I would get sleepy and leave some books on the floor. I was a fairly quick learner and loved looking at my collection of Little Golden Books. I hadn’t yet learned to read but was fascinated by words and the way the letters looked with their fancy little squiggles and tails.

It happened on a Saturday afternoon. I didn’t know the days of the week but I knew Saturday very well because it was the day Dennis mowed the grass so it would look nice for his friends. I was playing in the front yard while Dennis used the clippers to finish the lawn.

Ever the budding young wordsmith, I was playing with my Matchbox cars and sounding out words that rhymed. “Duck, truck, yuck.” Then it just came out. “Fuck.” I have no idea why I said the word and certainly didn’t know what it meant but was sure I’d heard someone say it.

Dennis, the outwardly devout church-goer who never drank, smoked, or cussed (except when the Packers lost, of course), was livid when he heard me.

“WHAT did you just say?” he yelled, as he pulled me violently by the left arm and knocked me face first into the lawn.

“Nothing,” I replied, tongue thick with terror and grass clippings.

“No, you said SOMETHING. Now what was it?”

“I said ‘buck.’”

“Buck?!”

“Yes, like what donkeys do, I guess.”

“Well, that’s not what I heard,” Dennis said, as he loosened his thick, black leather belt.

He started my public humiliation by hitting my bare legs. Then, right there in the front yard with Mike and the other neighbor kids watching, Dennis ripped off my play shorts and whipped my bare behind with a vengeance that far exceeded the small sin I had committed. I cried and screamed and begged him to stop until finally he pushed me aside and called me a worthless kid.

Comments

Honest and powerful

A tough read because of the subject matter. Some readers might not be up for this

Congratulations

Loved it, Lewis. Gritty, powerful, in your face writing.

Takes courage to write like this.

Well done. And good to see you make the long list.