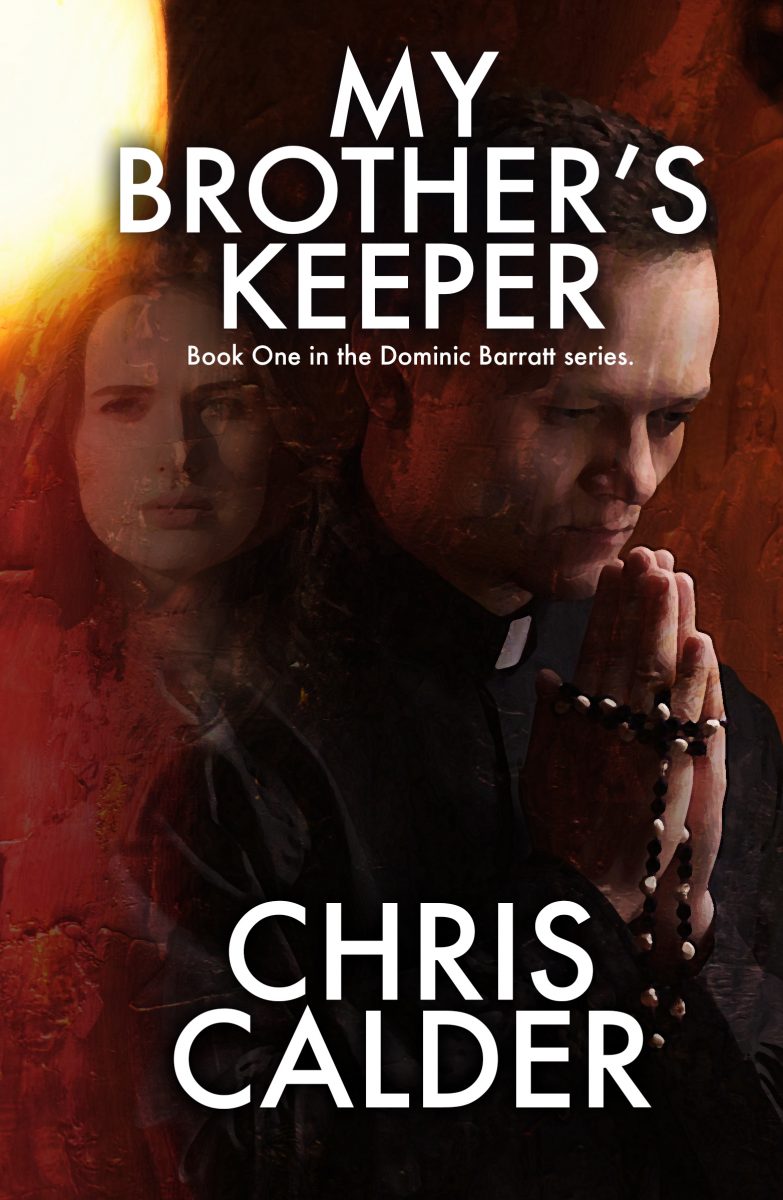

MY BROTHER'S KEEPER

CHAPTER ONE

Eleven-year-old Dominic stood in the corridor outside the priest’s room, his back against the wall, his senses dulled by the pervading musty odour of floor polish. In the distance, faintly, he could hear the banter of his fellow students at play.

He knew that corporal punishment was now used only infrequently at the school, and only when the offence was serious. Not like the old days, he’d heard, when beatings at Holy Cross were an unremarkable part of daily routine. From around the corner the steady tread of heavy shoes on the ancient oak floorboards heralded the arrival of the priest, and the boy was afraid.

Moments later the formidable figure of Father Gerald Gough loomed over him, a gigantic presence in the black cassock that was the uniform of the Jesuit order. Dominic looked up in trepidation; the priest’s expression was grave.

“Wait here, Barratt,” Father Gerald ordered, as he opened the door and went into his room.

The boy now feared the worst, he was about to be caned. He licked his dry lips and thought that being made to wait was as bad as the beating he expected.

“Come in, boy,” the voice boomed from within.

Dominic Barratt went in and shut the door behind him. He had not been inside this room before, or any teacher’s room; it was his first term at the school. Father Gough was sitting in a wooden chair placed side-on to a pine desk, with his arm resting on the top. He waved to signal the boy forward. Eyes downcast, Dominic moved closer to stand before the priest.

Father Gough’s expression softened. “You know that what you did was wrong?”

“Yes, Father,” the boy mumbled.

“What you did,” the priest said, “was pre-meditated. Do you know what that means?”

Dominic shook his head. “No, Father.”

“It means that you did it deliberately. You thought about it, so it was not an unplanned action.”

“Yes, Father.”

“That makes it worse than if you had lashed out when provoked.” The priest leaned forward. “You left the playground. You made your way to the washroom where you filled a bucket with cold water. You then returned to the playground, came up behind Henson and deliberately emptied it over his head.”

The boy looked at his feet. “Yes, Father.”

“Why did you do that?”

Dominic mumbled, “Because I didn’t want to hurt him, Father.”

The priest’s face took on a bemused look. “You didn’t want to hurt him?”

“I would rather have hit him with a cricket bat.”

Father Gough sat back, a half-smile on his face. “So you used water instead. I understand. Why? What had he done to you?”

Dominic looked down at his feet again. He did not speak.

“No answer? What did Henson do to you?”

“Nothing, Father,” Dominic mumbled.

Gough sighed. “Never mind. I imagine you believe it will make things worse if they think you’ve snitched on them.” He brought his hands together, locking his fingers. “But I already know what happened; I spoke to some of the boys who witnessed the incident. I wanted to know if you would tell me yourself.”

Dominic looked up, wondering what had been said, and by whom. He did not think it would make any difference.

The priest gestured. “Henson is a bully. He and his cronies pick on younger lads, especially new boys, and he seems to enjoy trying to make them feel inferior. Do you wonder why he does that, Dominic?”

The boy was surprised that the priest had used his first name. Maybe he wasn’t going to get a beating after all. “No, Father.”

“It’s because he is the one who feels inferior, so he’s trying to convince himself and his pals that he is superior to you. That’s what bullying is really about.”

Dominic glanced around surreptitiously, curiosity overcoming his feeling of apprehension. The walls were bare, with a large crucifix above the plain wooden bed. There was a wardrobe, a chest and a bookcase full of books. No sign of a cane.

Father Gough stood up. “You can go now, but I want you to think about this: When someone tries to bully you, remember that you are a better person than he is. Am I right?”

The boy hesitated. “But...”

The priest asked, gently, “Don’t you think that you are a better person than a bully?”

“But their dads are all toffs, and everyone knows I’m only at the school because of a scholarship.”

Father Gough sat down again. “Well, now.” He raised his eyebrows. “Don’t you realise that you have earned the right to be at this school? Whereas they are here only because their parents have money. Think about that.”

“Yes, Father.”

Gough put his hand on Dominic’s shoulder. “I hear they also make fun of you because you are thin, and tall for your age.”

“They call me a stick insect.”

“Really?” The priest stood up and patted the boy’s shoulder. “The next time a boy calls you that, just remind him that you are glad that you are tall, because it will make it easier for you to tip cold water over his head.”

It was a lesson Dominic never forgot.

“Will we have enough room in the car?” Philomena Barratt asked.

Her husband David cradled his coffee mug. “It’s going to feel strange, picking him up from school for the last time.”

“All I’m saying is that seven years is a long time. He’s got a lot of stuff.” Philomena busied herself clearing the kitchen table.

David lifted his mug; he hadn’t finished his coffee. “We saw his room at half term. He won’t have any more stuff than he had then.”

“It’s not like the usual end of term. It’s different this time; he’s leaving for good so he has to take everything. Did you clear out the car?”

David took a sip of coffee. “Last night. And before you ask, I put in the two empty suitcases and the cardboard cartons, too.”

“Don’t forget the brown tape. We can’t make them up again without tape.”

David put his mug down and Philomena immediately whisked it away. He grinned. “Will you for God’s sake stop nagging, woman.”

Philomena put the mug on the worktop, turned, and placed her hands on her hips.

“Good job for you that you were smiling when you said that.”

“You worry too much. It’ll be fine.”

“It’s the books. He’s got dozens, and they’re heavy.”

“Well, if we can’t get all his stuff in, it’ll have to go in the car, spread around.” He grinned wickedly. “And you’ll have to travel in the boot.”

She slapped his bottom playfully. “Idiot!”

Dominic was on his knees, pushing down on the top of his suitcase, which was full to the point of bursting. He held it down by leaning on it with one hand, whilst closing the zip with the other. With a satisfied grunt he sat back on his heels, just as Father Gough appeared at the door.

“All packed and ready?” the priest asked.

“About as ready as I’m going to be, Father.” Dominic looked around. “Until my parents get here. They’re bringing suitcases.” He went across to the bookshelves lining an alcove. “These could be a problem, though.”

“Leave any that you don’t need; I’ll pass them on to other students.”

“Can I come and see you sometimes?”

“I’ll be disappointed if you don’t.”

Dominic ran his fingers across the tops of the books on one of the shelves. He pulled out a slim, well-thumbed volume and flicked it open. “Remember this? The Joy of Psychology. You gave it to me during my first term.”

“Yes.”

“It changed my life, literally.”

“Then I’ve a lot to answer for.”

Dominic held it up. “Do you know, Father, there’s a connection between this book and that guitar in the corner?”

Gough smiled. “Robert Henson?”

“Who became a close friend, thanks to you, and this little book. He gave me the guitar when he left last year. I’m leaving that, too. I tried to learn how to play, but didn’t get beyond making horrible noises, and breaking strings.”

Gough sat on the edge of the bed, which was covered in neatly stacked piles of clothes. “Have you made up your mind? Are you going to major in Psychology or Law?”

“Psychology. It’s more interesting; for me, anyway.”

“Where do you hope to go?”

“I’ve applied to three, could be any of them.”

“There’s talk of a change in the rules; from next year or the year after, students will have to pay fees for university places. Probably a thousand pounds.”

“It won’t affect me, thank goodness. I don’t want to burden my parents with any more bills.”

“Despite your scholarship, it can’t have been easy for them.”

Dominic placed a few more books on the floor. “It’s been tough for them. Mum does two jobs, and Dad works all the overtime he can. They haven’t had a holiday in years, and that won’t change until after I’ve graduated.”

“Your parents are an exceptional couple, and you are a lucky lad.”

“I know.”

“I’d like to see them before you leave.” He stood up. “Let me know when they get here.”

On the motorway, David pulled out to overtake a slow lorry. “Has he decided what he wants to do after university? He’s not said much to me.”

“He wants to be a priest.” Philomena sat with her hands in her lap. “I’m sure of it.”

“He said he was thinking of going into advertising. The pay’s good, and that’s what advertising is all about, psychology.”

“The priesthood!” Philomena looked across. “Can you think of a better use for a psychology degree? Helping people and all that.”

“Let him make up his own mind, Phil.”

“Course he’ll make up his own mind. He’ll be a priest.”

“You’re amazing. Once, just once when he was – what, eight? nine? He said he thought it would be good to be a priest. But once was enough for you.” He shook his head. “You know what I think?”

“What?”

“Priests are trapped. Once a priest, always a priest.” He gestured. “That’s it; for life. Dom’s bright. Though looking at us, God knows where he gets it from. I can’t see him being happy as a priest, for the rest of his life.”

She was silent for a few moments, then she looked at him. “Twenty-four years we’ve been married. Do you feel trapped, Davey?”

David put his head back and lightly slapped his forehead. “Of course not. What a question!” He glanced at her. “Sometimes I wonder how your mind works. We are married. Happily married; it’s different.”

“No, it’s not. You don’t feel trapped and I don’t feel trapped, so why should Dom if he becomes a priest? If that’s what he wants, it’ll be right for him. We’ll be together for life, God willing, and he would be a priest for life.”

Three years later, on an autumn evening, student Hazel Price folded her arms, leaning over the viewing gallery wall at the university squash court.

“He doesn’t look happy,” Hazel observed.

Hazel and her friend Gillian, both students at the university, were watching a game in which Gill’s boyfriend Brian was being soundly beaten.

“He’ll be grumpy for the rest of the evening.”

Hazel was unashamedly admiring the opponent. “Who’s the new guy?”

“Dunno.” Gill shrugged. “Brian always plays against Pete. I’m guessing Pete couldn’t make it. I’ve not seen this one before.”

“Quite dishy, isn’t he?”

“If you like tall guys. OK for you; I don’t date anyone over six feet. I did once and it was ridiculous. Doesn’t work when you’re only five foot four.”

“Keep an open mind; they say love is blind.”

“Yeah, right.” Gill smiled. “Stop drooling. You’ll meet him when they join us in the bar.” She turned. “They’ve nearly finished; come on, let’s go down.”

Twenty minutes later the four were at a table in the crowded, noisy, students’ bar. Dominic had followed Brian.

“We got the drinks in; you owe me five pounds thirty,” Gill said to Brian.

“Is that all? A cheap round.”

“Five thirty’s not for all the drinks, just your beers.” She looked at Dominic. “I got you the same as Brian, Dominic; hope that’s OK.”

Dominic replied, “Fine, thanks.” To Brian he said, “Let me get that.”

“It’s OK, Dom; you can get the next lot.” Brian reached into his pocket. “Here’s six pounds,” he said to Gill. “Why do I need cheering up?”

Gill grinned. “I’m guessing that after being hammered on the court, you do.”

Brian grimaced. Dominic decided to change the subject. “What are you reading, Hazel?”

“English and Social Sciences; first year. I want to make a career in teaching. You?"

“Psychology and Law.”

“A toxic mixture. Are you going into politics?”

Dominic snorted. “Good God, no.”

“Then why Law?”

“Politicians fascinate me. That’s where the psychology comes in.” He lifted his beer. “I haven’t seen you around before.”

Gill cut in. “She doesn’t live on the campus.”

Hazel said, “My aunt lives in the city. She offered me a room; I couldn’t refuse.”

“Dom’s taking his finals this year,” Brian said. “Shame he doesn’t want to go into politics, I think he’d do well.” He frowned. “But maybe not. He’s too honest.”

Gill pointed at the clock on the wall. “Don’t forget, we’re going to the big debate tonight.”

Brian glanced at his watch. “Shit; we’d better get a move on.” He picked up his mug and drained it.

Gill turned to Hazel. “You coming?”

Hazel was looking at Dominic. She answered without turning her head. “No, thanks. I’m really not that interested in saving the rain forests.”

Brian picked up his sports bag. “OK, see you guys later.”

“See you,” Dominic said, raising a hand. He turned back to Hazel. “I’m surprised. Don’t you want to save the planet?”

“I couldn’t possibly do it on my own.” She smiled. “Anyway, I’m busy right now.” She put her elbows on the table and leaned forward. “What do you do with your weekends, Dominic?”

“Nothing exciting. I study and relax a bit.”

“On your own?”

Dominic was starting to get a feeling for where this was leading. “Usually. Why do you ask?”

“Do you go to the cinema?” She pushed a wayward strand of blonde hair back behind her ear.

“Not much, I haven’t been for ages.” He tilted his head. “Are you fishing for an invitation?”

She grinned. “I don’t fish – for anything.” Reaching forward, she put a hand over his. “But it’s good of you to ask, and I accept.”

They met the following Saturday evening at the cinema, and later went for a meal in a pizza parlour. When she was finished, Hazel pushed her plate aside.

“More than I can handle.” She dabbed her lips with a paper napkin.

Dominic had not quite finished his pizza. “Would you like a dessert?”

“Couldn’t possibly.” She gestured. “But you go ahead.”

“Not for me, either. Coffee?”

They ordered coffees, which were brought to the table. Completely relaxed, Dominic tore open a sachet of sweetener, and drizzled it into his cup. “I’ve had a lovely evening.”

Hazel’s eyes crinkled as she smiled. “Me too. But it isn’t over just yet.”

“Have you got far to go?”

“Blake’s Hill, it’s about fifteen minutes on the tram. One of the things I love about this city, you can get from anywhere to anywhere quickly and cheaply.”

“I’ll see you home, if you like.”

Thirty minutes later, Dominic followed Hazel up the path of her aunt’s semi-detached Victorian house.

“Here we are, number seventy,” she said.

Dominic observed, “There are no lights on.”

“She’s away for the weekend.” Hazel opened the door. “Come in.”

Dominic stepped into the hallway. Hazel took off her coat and draped it over her arm. She pointed at a door on the right. "The living room. Go in; take your coat off, and get comfortable.”

“Thanks.” Dominic went into the room and removed his jacket. Hazel stood in the doorway. With her slim figure, pretty oval face, and long blonde hair tied back, she looked gorgeous. She tilted her head.

“Coffee or tea? Or a beer, if you prefer.”

“Coffee, thanks.”

“White, coming up. With a sweetener, like you had in the pizza place.”

Bright, pretty and observant, too, he thought, as he settled into an armchair and stretched out his legs. The room was comfortably furnished, in a somewhat dated style, with a three-piece suite around a low coffee table. Hazel returned, carrying two mugs. She put one down on the table, close to Dominic. Holding the other in both hands she sank into a corner of the settee, and drew her legs up beside her. “What are your plans?” she asked, “after uni, I mean.”

“Nothing fixed yet. One of my friends works in advertising. He says he can fix me up with an interview, when I’m ready.”

“Advertising?” Hazel’s eyebrows arched. “Well paid, I’m guessing.”

“Probably. To be honest I’m not mad keen, but it’s a start. And having a job to go to can’t be bad.”

They chatted easily for fifteen minutes, then Dominic glanced at his watch. He placed his empty mug on the table and stood up. “I’d better be going, it’s getting late,” he said, reaching for his jacket.

“You live on the campus, don’t you?” Hazel stood up and put her mug on the table.

“Yes, I share a room.”

She took a step closer to Dominic; her lips parted in a twisted smile. “I can do that, too. Will they send out search parties if you aren’t back tonight?”

-------------------------------------- oOo ----------------------------------