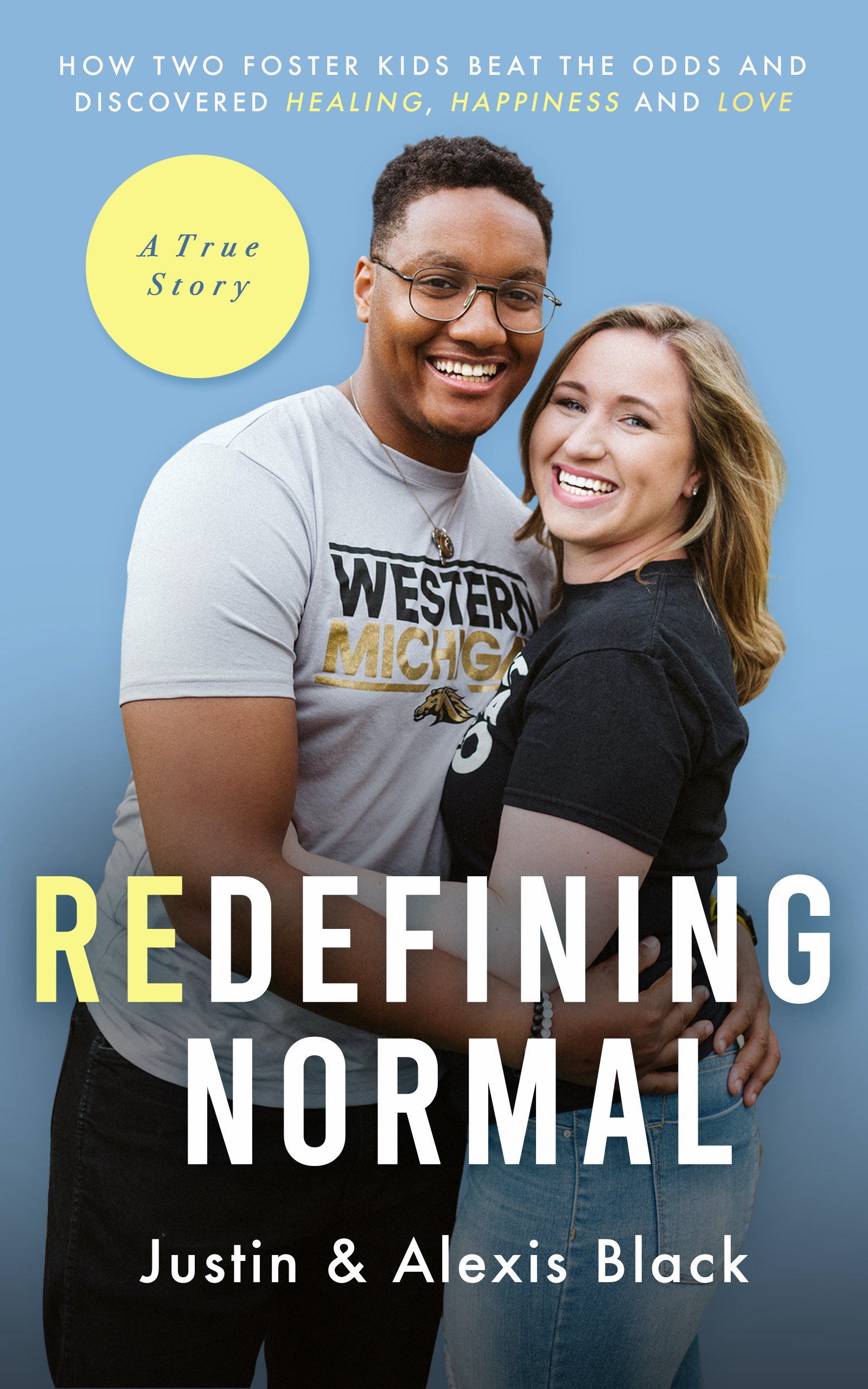

Redefining Normal: How Two Foster Kids Beat The Odds and Discovered Healing, Happiness and Love

INTRODUCTION

In January 2020, Justin and I were on our way to South Africa. I was going to work and volunteer and Justin was going for his fifth study abroad program. On our way, we stopped in several cities, including Luxor and Cairo, Egypt, where we took in such sights as the pyramids of Giza and enjoyed kofta and koshari. We were exhilarated to be on an adventure together. Everyone knows what happened two months later. Along with so many others, we were emergency evacuated, flying home to Northern Michigan, where we spent two weeks quarantined in an RV just outside my parents’ bi-level mid-century style house surrounded by 20 acres of land.

Whirling from the derailment and mourning the loss of the rest of our trip, we set upon an idea. We began writing the book you are holding now. Perhaps it was the confinement that helped us to decide it was time to explore our demons by recounting our story. Having survived so much, and having found each other, we knew the story would ultimately be one of triumph. We also knew that writing about the darkest moments of our childhoods would not be easy. But there we were, furiously writing at the table in the RV’s tiny kitchen.

We are writing about our journey for two reasons: we want to share our story in the hope of helping others, and we wanted to grow closer to one another before becoming husband and wife. Most people we know have either been in or are currently in unhealthy relationships, especially those who are, like us, former foster youths. Hailing from Detroit and Flint, Michigan we have seen too many adults spend their entire lives trying to heal from their difficult childhood experiences. Foster youth are particularly at risk of repeating unhealthy cycles of behavior. We were and continue to be on a mission to unlearn all of the unhealthy patterns we witnessed early in life, and to make sure that we don’t pass these things down to our children.

We are not perfect, nor are we experts. The purpose of this book isn’t to tell people how their relationship should work or even to serve as a model relationship for others. It is only to share our experiences and show people that there are healthy ways of both loving and receiving love, and that we all have the power to build a life of our choosing. We see it as our duty to help others, because so many people have poured love and support into our lives and helped us get to where we are today. We hope that by sharing what we have learned we can save others from going through similar heartache. We are committed to being transparent and vulnerable on our journey to healthy love.

Our story is broken down into four sections with different themes. The first three sections consist of our personal narratives as well as stories on various topics. We had to go on two individual journeys of self-discovery and healing so that we could come together in agreement—the final section of this book.

Although we dive deep into our experiences with the child welfare system, this book is for anyone yearning to understand the components of both healthy and unhealthy relationships while in the process, learning to love themselves.

Here are some statistics you may find startling:

On any given day, there are nearly 437,000 children in foster care in the United States, with 700 kids entering the system each day. Neglect—a common symptom of poverty—is the number one reason youth end up in foster care.

There are over 125,000 children waiting to be adopted—most wait three or four years on average.

It has been estimated that 60% of all child sex trafficking victims have histories in the child welfare system.

On average, for every young person who ages out of foster care, taxpayers and communities pay $300,000 in social costs over that person's lifetime, with 26,000 young people aging out every year multiplied by $300,000 per person equals $7.8 billion in total cost.

*These statistics are pre-COVID-19, meaning that they’ve been since exacerbated.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

We’ve consulted e-mails, messages, posts, consulted with several of the people who appear in the book, notes, and memories to construct this memoir. To protect the identity of some of the individuals in this book, we’ve changed the names and re-created dialogue, while remaining faithful to what really happened. We occasionally omitted people and events, but only when the omission had no impact on either the veracity or the substance of the story. We aren’t able to include everything that’s happened to us or what we’ve overcome in this short book. This was meant to give you merely a glimpse of our lives, and how we’ve beaten the odds set against us.

We do want to provide a trigger warning with regard to domestic violence, trauma, sexual assault, and more.

All statists are cited on our website at re-definingnormal.com/booksources.

PROLOGUE

Alexis

I was 13 when I became an orphan and a ward of the state. My mother had died years earlier and my father had just been sentenced to 15 years in prison. At 20, when I was a junior in college, there was much I had yet to understand about the way trauma had shaped my understanding of life and love.

Justin

Due to my parents’ drug addiction and neglect, I entered foster care at 9 years old. I lived in four homes over the next 12 years. With no parental support, I arrived at Western Michigan University at 19, my sense of self extremely fragile. Chaos, poverty, and violence had profoundly influenced my understanding of the world and my place in it.

PART 1: WORDS ON AN INDEX CARD

What the Statistics Say:

65% of children in foster care experience seven or more school changes from elementary to high school. Foster youth lose between four and six months of educational progress with each school change.

Only 56% of foster youth graduate high school while less than 3% of foster youth graduate from college.

What Does God Say:

“I am fearfully and wonderfully made”

(Psalm 139:14).

ALEXIS:

After five months of studying and self-discovery among the lush green mountains and beautiful acacia trees of Cape Town, South Africa, I flew home to face something I desperately wanted to avoid. While I was abroad, my boyfriend at the time, Shawn, had been living in my apartment rent-free. We had been dating--if you could call it that--for eight years, and in that time, I’d been on a roller coaster of emotional violence and manipulation. It had peaked in a new way while I was gone.

Shawn was supposed to care for my cats-- Leo, Lily and Leia -- whom I’d acquired at the recommendation of my therapist. I doted on them as any pet owner does, but due to very dark and specific memories, which I will address later in the book, their safety was of paramount concern to me. Shawn knew this, and used them to inflict torment. He told me that he was neglecting to feed them or clean out their litter boxes; he even denied them clean drinking water. I had to make a series of desperate calls to friends, begging that they come to my house and intervene on the cats’ behalf. Far away and helpless thousands of miles away, Shawn had found the perfect way to torture me and leave me in a state of chronic anxiety.

Shawn victimizing my defenseless therapy pets shifted something inside me. After years of abuse I was finally ready to leave him, freed of any sense of obligation to a man who clearly felt no obligation to me.

I came home to an apartment reeking of cat urine. Household items were strewn all over the floor. I confronted Shawn and told him that I couldn’t pretend this was an acceptable way to be treated. I had lived like that for too long. I was leaving him.

“So, you don’t want to marry me anymore?” He stood at the top of the stairs, yelling down at me. “You don’t want to have kids with me anymore?”

It was a sign of the deep dysfunction of our relationship that he could have asked those questions. It would have been funny if it hadn’t been so painful.

Meanwhile, I did not know how to ask for help. It certainly hadn’t occurred to me to ask my foster parents at the time, Kim and Brian, whom I’d known for seven years and who had given me unconditional love. I never would have thought moving home with them was an option. I have always been too proud--and fearful--to ask for support of any kind from anyone. I was used to figuring everything out on my own. Growing up, I hadn’t had much supervision--my biological father was always at work and my mother passed away when I was only six. I was 13 when I entered foster care and have felt self-reliant ever since.

Mercifully, my foster parents offered to help without having to be asked. Kim and Brian came over to help me pack my belongings and move them back to their house. It was just the lifeline I needed. But in order to accept their support, my cats weren’t allowed to come with me because they were allergic to them. I had to find another temporary home for my cats until I could have them again. It felt like I was constantly putting them in pet foster care and I was the unstable, irresponsible parent that couldn’t support them. The last thing I ever wanted to be was a reflection of my own biological parents.

*

After moving home, Kim and Brian asked me to promise that I wouldn’t date again for at least a year. They wanted me to figure out who Alexis--without a boyfriend--really was. I had dated Shawn from the age of 13 to the age of 21 and my identity had been entirely subsumed by him.

I was running out of the scholarship money that paid for my rent and living expenses, so I chose to apply for the Seita Scholars Program, a scholarship program for foster youth receiving higher education. In order to accept the scholarship, I had to live on campus in Kalamazoo, Michigan at Western Michigan University (WMU) and participate in the Summer Early Transition (SET) week—staying on campus for a week with your cohort to build bonds and begin college together. I had already attended WMU for two years after transferring from The University of Michigan-Flint, and felt this was unnecessary, but hey, there was free food for the week!

It was then that I had to decide: keep all three cats or accept this scholarship. This decision ripped me apart, but thankfully, I had a wonderful friend that adopted Leo and Lily so that I could continue my education.

I moved into Henry Hall on WMU’s campus to start SET week. Kim texted me:

Kim: “Henry Hall! That is where Brian and I lived and met freshman year. :)”

Me: “Awww omg!!! Well, I’m with all freshmen so no luck finding my soulmate. Lol”

Kim: “You never know!”

Me: “Kind of doubt it! Lol

They are all babies lol I feel so old.”

Walking into Bernhard Center, a place for students to eat, interact and connect on campus, I felt confident and cute since I was an upperclassman, and these were “freshmen babies.” I walked into a busy room with much conversation. In an attempt to somewhat isolate myself, I found a table where few students sat, which was nearly impossible. The only empty seat I could find was with three other boys.

One guy named Justin tried to flirt with me by complimenting my tattoos. He asked me how my summer had been and I told him that I had just returned from South Africa and that I'd gotten all five of my tattoos there over the course of two days. He was shocked and very impressed by my bravery to do so. It was fun to flirt back, although I thought he was too young for me. He hadn’t even officially started college yet! He’d had his senior prom only a few months before.

*

I sat with Justin and several other kids at lunch. I looked up and saw a student at another table take off his hat and pray. I paused and thought how beautiful it was-- I had never seen someone my age do that.

Shortly after, a group of guys on the football team sat down a few tables over. I commented on how “fine” one of the guys was. One of the people at my table stood up in an attempt to play matchmaker and called the guy over, saying I wanted to talk to him. I was mortified. He came over and said, “What’s up?” with some annoyance present in his voice. I didn’t know what to say and the guy at my table chimed in, “Give her your number so y’all can talk.” I instinctively handed over my phone without saying anything and he replied, “Text me” while handing back my phone. My stomach was full of knots and I started to sweat. I looked around the table and noticed Justin walking out of the lunchroom.

The football player texted me shortly after saying “What’s up? What you tryna do?”

I knew what that meant. Honestly, I didn’t expect anything more from the football player because I’ve allowed myself to be talked to like that for years and used for my body. I tried to brush off these feelings, but I still had the idea that if I wanted attention or affection, I’d have to give up a piece of myself in order to do so.

Comments

Congratulations

Well done becoming a finalist. Your book is amazing and inspirational. God bless.