Introducing your narrator, M. M. De Voe:

Hello.

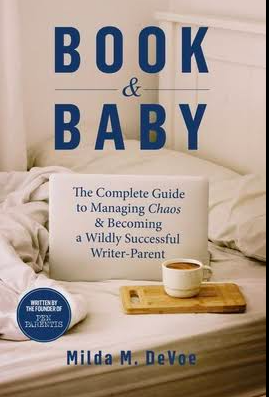

Never did I ever think I was going to start a nonprofit. Or get married. Or of all things, become a mother. My journey to founding Pen Parentis is as randomly roving as a book by Proust. Yet here I am, an award-winning writer with two children, married more than 25 years, and happily running a successful organization that helps keep writers on creative track after they start a family. In writing circles, there’s a dichotomy between “planners” who outline their plots and then fill in the details to get to the end, and “pantsers” who basically start writing and end up wherever their imaginations take them—plotting by the seat of their pants, as it were.

In writing, I am a “pantser” and it turns out, in life I am a “pantser” too.

As a child, I was a performer. I was the kid who organized skits at holiday gatherings, who got my three younger brothers and three younger cousins and sometimes my two neighbors together with finger puppets, or marionettes, or just the soundtrack of a musical or a movie and ourselves, and who created stories and dramas for all of us to act out. There were variety shows in the driveway, sing-alongs on my grandmother’s stairwell, Martha Graham-style dance numbers with ribbons or balls or long scarves on the lawn in Texas—these often were interrupted by someone stepping on a sticker in their bare feet. (Stickers are vicious ground-growing weeds that culminate in seeds that are basically a pea-sized hard round ball with dozens of sharp spikes. They’ll penetrate any callus, and god forbid you fall over in a patch of them.) Our earliest audiences were always adults, sometimes appreciative, usually full of constructive criticism: That’s nice but maybe you could practice some more, what are those terrible lyrics, is this even appropriate for kids, why are you using my power drill as a prop?

In comparison to stepping on a sticker, no amount of artistic criticism is painful. It’s all just words.

I loved the applause. I sang all the time: around the house, in the shower, at the side of the road waiting for the school bus. By the time I was nine, I was convinced I would be a world-famous opera singer who was as smart as Sabrina from Charlie’s Angels and looked like Cher. I started entering talent shows. In third grade I floored my elementary school teachers by belting out Helen Reddy’s “I am Woman, Hear Me Roar” to a standing ovation. At home my mother told me I was never to sing another song like that.

To this day I don’t know what she meant. Feminist? Powerful? Was it my high-heels and sparkly pantsuit, borrowed from a friend? Or was it the pop-star quality of basking in the attention of strangers that she was objecting to?

I kept singing. I joined choirs. Church choir, middle school musical, high school choir… I played the lead in every musical, the supporting comedic character on alternate nights. I loved to perform. I signed up for drama, jazz and ballet classes at our local community center. I played the piano, took voice lessons and briefly attempted the guitar until the F-chord gently showed me that this instrument hated me. I loved the immediate response of performance: when I did great, it garnered applause. When I messed up, that was equally clear. Performing live taught me that every audience wants you to succeed—and even when you fail, they expect you to dust yourself off and keep at it. Live performance taught me grit.

When I was fifteen, I was sent for two years to a Lithuanian boarding school in Germany. To understand this random event, you have to know that I was born to Lithuanian DPs (displaced persons). Both my father and mother had parents who escaped the Soviet occupation of their homeland. In today’s parlance, my parents were “Dreamers.” After coming of age in different Chicago Lithuanian immigrant neighborhoods (yes, there were two of them!), my parents met, married, and relocated to Texas to escape the 1966-70 race rioting in Chicago’s South Side—at the time my parents were young, forward-looking, college-educated adults who believed passionately in Civil Rights and equality for all, but not in bloodshed for any reason. I was their first child and raised bilingual, with a strong sense of Lithuanian identity in the middle of Texas –I was frequently instructed to represent my parents’ homeland, so in my childhood, I spent an inordinate amount of time wearing a Lithuanian folk costume and explaining the mushroom- or potato-based foods that I was handing out for sampling—not just during the annual “Heritage Days” at school but also during “International Day” at the local shopping mall. Potlucks at church or school always meant that we had to educate our neighbors on Lithuanian cooking. Culture through food.

During the Soviet Era, West Germany boasted of the only Lithuanian High School in the free world. Lithuanian parents from all over the world sent their kids there for at least a year (mine begged some nuns to give their kid a scholarship) and I and other “displaced” Lithuanians (we were called DPs) were instructed in the language, history, and literature of a country that had been forcibly occupied by the Soviet Union after the Second World War. We were told we needed to keep the culture alive because in the Soviet Union, even praying in the native language was illegal. We were told that strict Roman Catholicism was patriotic. Folk dancing in costume was a political demonstration. Folk songs were subversive and many had hidden or double meanings.

Outside of my family, I knew zero other Lithuanians who could tell me whether any of this was true, so I simply believed it.

(Now I know there were isolated Lithuanian families like mine all over Texas, but back then I was craving community so desperately that I once wrote a letter to a complete stranger whose first and last names were Lithuanian. I found this person I wanted to befriend quite randomly in a Houston phone book, and literally pleaded and begged them to write back. They never did.)

This cultural indoctrination was important to my parents. We were not wealthy: my three younger brothers and I were raised in the country outside of a small college town where my father had the salary of a postdoc chemistry researcher for most of his life. My mother ran a tiny Montessori school that never charged more than the bare minimum, because she believed all children deserved a great preschool education (she would have run that school for free if someone had donated the requisite pink tower and maps and covered the expenses of feeding the school’s geese and occasionally painting or exterminating the fire ants in the schoolyard). I survived overseas for two years on a $50 per month allowance, and that, to me, seemed extremely generous since our food bill for six people, three of whom were active growing boys, was $100 per week—which again, seemed like an enormous expense that the family was always trying to cut.

Money was always an issue, but one that I was able to grow beyond. I learned to find free events to attend, to take advantage of available opportunities, too recycle, to be thrifty. I learned to make do with what I had, and to shop around for bargains. I learned that style was less expensive than fashion — and more valuable in the long run. I learned that experiences were longer-lasting and more transformative than objects, and that ideas cost nothing and could change everything. It was an important period in my life.

After my two years in boarding school, I returned to the United States fluent in both Lithuanian and German, and I entered college a fiercely activist anti-Soviet music major. I attended a tiny Catholic women’s college in Baltimore brilliantly named the College Of Notre Dame Of Maryland. They have since changed the name, but oh what a delicious acronym to toss around ironically while I was a student! The college’s chief strength was that they, as a nun-driven school, were extremely feminist and quite appreciative of young women’s inner fortitude and personal drive (if you know any nuns in person you will understand this) and gave us free rein and lots of administrative support to do whatever it was we wanted to do. You just had to find the rules that gave you the permission. As Freshman class president, I learned that heavy bureaucracy could either drive you up a wall, or (if you could keep your head), you could learn to check off the infinite boxes and get whatever you need. The process of dealing with a bureaucratic Catholic school system would serve me well when I eventually began to apply for government grants.

This time period was also where I learned about grassroots marketing. There were layers of flyers for contests, free events, and job offers posted on the bulletin boards at school – if you blew by them without reading, you’d never know what was going on. I was the kid who attended all the free events thrown by the Student Activities Committee – often the only student in the audience who wasn’t required to attend, I was able to personally meet all the folk singers, authors, comedians, motivational speakers, etc., that came through the college. I learned a lot from these one-on-one conversation with professional entrepreneurs in the performing arts. They were scrappy. They would play an empty room for money. They would use photographs and memorabilia to turn a disastrous performance into a fabulous newspaper article or interview that made them look great. They were marketing before marketing was even a major.

In my junior year of college, I also won my first national writing contest. Remember I am not from a wealthy background. My three younger brothers all needed to attend the Lithuanian boarding school for at least a year. This was my parents’ priority: College was on me to fund. My parents could cover my textbooks, but even that was a hardship. My four-year college experience was funded on a full academic scholarship that included room and board, but I still had to come up with my own pocket money. Since international travel was high on my list of To-Dos, and credit card offers had been pouring into my mailbox from the minute I first opened a bank account, I was already $900 in debt by my junior year. To a college student, this was a desperate, impossible amount, even though I was earning $6/hour at a “great” part-time job in a fitness center. Imagine my delight to find a college poetry contest with a top prize of $1000 thumbtacked to the English Department’s cluttered board.

I submitted a villanelle I had written for my prosody class, and to my great delight, I won the grand prize.

Not only did this create a little rocklike seed of faith in my writing talent, it made me believe in the power of a thumbtacked flyer. I submitted further poetry to various other contests, always things I had written for class. While I had always adored languages (I had by then added classes in Spanish and Italian to my Lithuanian and German), this was the first time I realized that I was not a bad wordsmith, even in my native tongue!

I was a busy kid in college. Not only did I dance in a Lithuanian folk dance troupe and attend political demonstrations in Washington DC nearly every weekend, but also, on campus, I started a drama club, directed a musical, founded a singing telegram company, and revived three old College traditions (Sing-Song, the faculty talent show, and a candlelit Ivy Walk to sing to the seniors). I would discover a need in the community (or in myself!) and then just start making things happen. It was an active, busy time – filled with passionate late-night arguments about politics, creativity, and the arts. I knew what I wanted in life and was driven to get it.

And in junior year, after winning that contest, I felt the limitless possibilities of choice. Debt-free at last, I took a background role in a John Waters movie, and when it wrapped, I ran away with a troupe of jugglers for a summer, and they became my best friends for life. I had vague ideas of a glamorous future: I would either join an opera company and tour the world, or I would get a job in the Lithuanian consulate and train to become an ambassador. Meanwhile, I was taking 19-23 credits per semester, performing whenever possible, and dating half the people who attended Johns Hopkins, Loyola, and the Naval Academy in Annapolis, all while staying on the Dean’s List.

I didn’t realize this was unusual.

And then in March of my senior year in College, Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Union. My friends and I - globally - had succeeded. Lithuania was free. I no longer needed to attend demonstrations, folk-dancing was instantly downgraded from a political event to a charming if slightly odd little hobby, and even my fluency in this difficult foreign language was suddenly archaic and bizarre instead of brave and fiercely patriotic. All of this happened overnight. I lost my core identity in one newspaper headline. I was no longer a freedom-fighter.

I was nothing: just a girl who had been born in a small town in Texas and called herself Lithuanian.

But I still had my singing. I still had performance. I still got applause.

What I didn’t have was any career guidance.

The Music Department faculty consisted of two excellent pianists, an adorable but rather dotty nun who directed the choir, a part-time flautist and a part-time voice teacher who was best known for playing the lead in “The Bird Cage” at a local dinner theater. They were all loving and nurturing of talent, but they were not managers. I knew I loved performance, but after college, what did artists do to get jobs? I had no idea. No one told me there was such a thing as graduate school for opera, so I auditioned for something I saw on a flyer and got into an acting school called AMDA – the American Musical and Dramatic Academy in New York City. It started three days after my twenty-first birthday, which coincidentally was also my college graduation day.

So that’s what I did. I moved to New York City, and found I was home.

Becoming a Writer

I loved NYC with all my heart. While I felt empty from the lack of international politics, no longer was it weird that I was Lithuanian. Most people I met had vaguely heard of the country, or at least that the Soviet Union had broken up. Politics was acceptable cocktail party conversation here, and so was culture. I was an avid reader, and that too, was valued. I spent two years working hard on character voices and learning a musical theater repertoire. I’d had no formal training in drama and here’s how naïve I was: at my first monologue audition instead of facing the judges, I pretended there was an invisible person on stage with me and played the monologue to her. The judges giggled until one kind soul gently told me to place my invisible partner in the back row of the audience.

My last year of acting school, disaster struck. I developed vocal nodes from the late nights, lack of nutrition, and endless loud and lunatic character roles. With a lack of real income and no medical insurance, I was unable to do anything but go on six weeks of vocal rest. My friends were auditioning for world tours and cruise ships, and I was writing responses on a small notebook like a mute person. My new boyfriend was supportive and kind, and though we practically lived together and did in actuality work together, despite the intimacy of existing 24/7 in each other’s company, I wasn’t comfortable with letting him in on my financial situation (destitute with no prospects), so he was unable to help. I never dreamed that I would end up marrying the guy. I never dreamed I would marry anyone.

Once my nodes went away, I discovered I had permanently damaged my vocal cords and would probably not be able to sing professionally. Once again, I had to completely reinvent myself. Instead of the musical theater tours I’d dreamed of, I threw myself into plays – I used my organizational skills to help found two off-off Broadway theater companies in a row. I was on the management team of the second one, and learned a lot about getting people to attend shows – “butts in the seats” it was called, the bane of all small theaters, there were often more people on the stage than in the house! I grew to love writing press releases and making connections with strangers at networking events. Meanwhile, I was getting serious with the boyfriend – we had moved in together and because my ultra-Catholic parents were deeply unhappy that their only daughter was “living in sin,” we were contemplating marriage to appease them. But he and I had a scheduling issue. He had gotten a day-job to make more money and his hours were 9-5 and once my theatrical career took off, mine were 9-11pm and weekends. So I started looking for something else to do.

To pay my half of the rent, like many actors in NYC, I had been working as a temporary employee. In the beginning, I cycled through all the financial firms in New York: Bear Stearns, UBS, Lehman, even BlackRock. I worked a few law firms too—mostly what I got out of those were MeToo moments. My employers found me quick to learn and were constantly offering me full-time employment, which I airily declined, telling everyone I was an actress. They loved it. Many of them even came to my shows. But rent still had to be paid, and I soon landed a gig that would last nearly five years: although I officially still worked for the temp agency, I had been placed at a Japanese bank on the executive floor as the assistant to the General Manager of North America. This meant I had an enormous and gloriously empty desk in a lush but tomblike corner of an elegant skyscraper with high ceilings and enormous flower arrangements and deep carpets to muffle footsteps. Apart from typing the occasional thank you note in English and booking his golf tee times, I had absolutely nothing to do except to serve tea and look pretty. Serving tea was a headache and required many consultations with the Japanese office manager who would peek in on the video cameras and let me know which gentleman was to be served first, but the rest of the time on that floor was my own. The only caveat? I had to look busy.

I wasn’t permitted to read the newspaper or a book. I had to actually sit up and be alert unless I was working on my computer. So I started to write a book.

Comments

Such a well-written book. …

Such a well-written book. THe narrative is well paced and tight. The background to how you got here is fascinating. I love the premise. Many writer parents are in this predicament. Congratulations.

Fascinating Story

You've included wonderful anecdotes to introduce us to your life, well based and quite interesting. Well done!