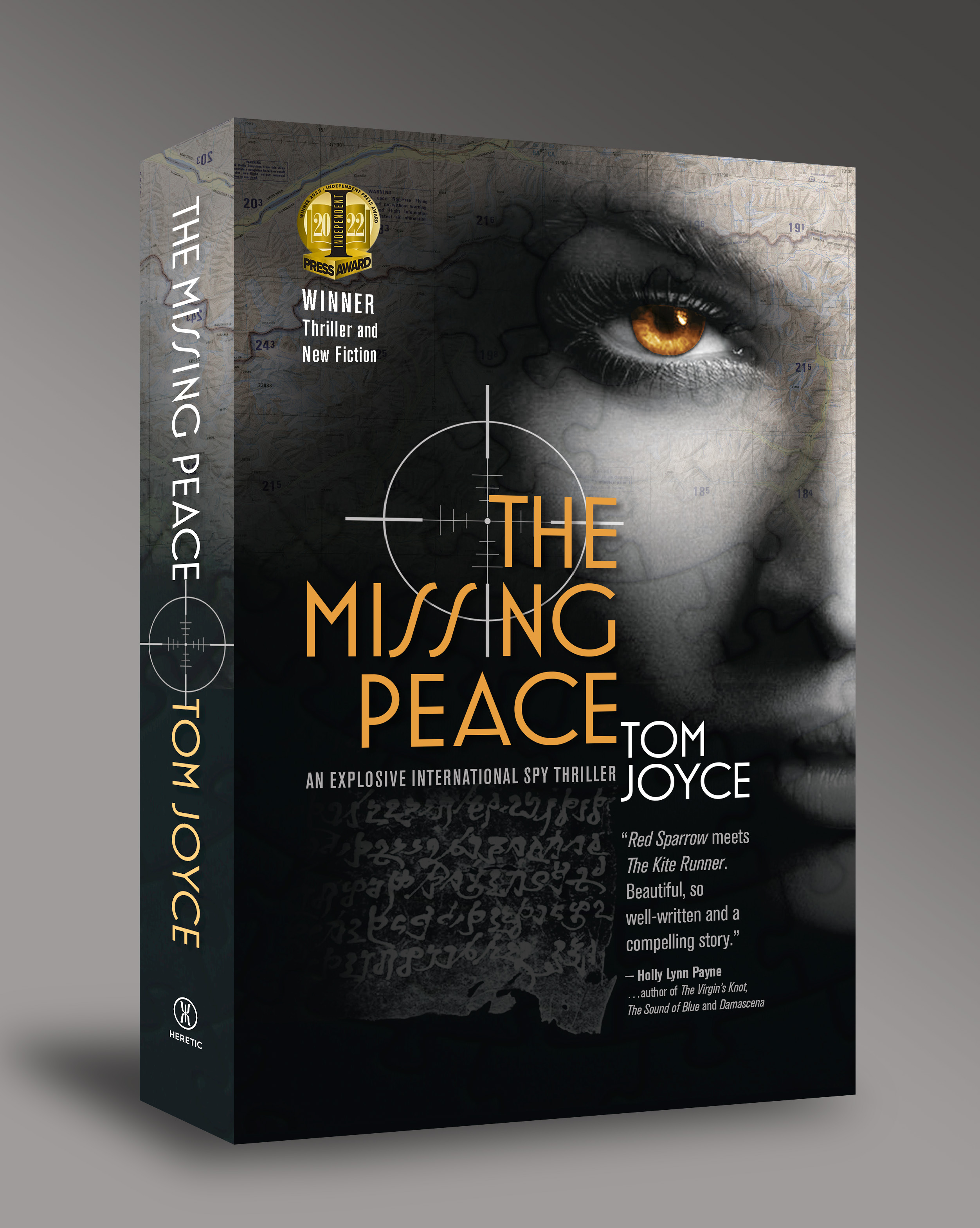

The Missing Peace

PROLOGUE: TUESDAY, 14 FEBRUARY 1989 • THE HINDU KUSH, AFGHANISTAN

The air smelled of ozone, tasted metallic and felt like the edge of a knife. Somewhere behind the pilot’s eyes, a memory ignited, jolting him back into consciousness. He heard no sound of life in the aft cabin, nothing but a violent wind scouring a fractured canopy somewhere above him, until his own voice began to play back like a damaged tape recording in his ears.

Yuriy… pozhaluysta…skazhite mne…

He could neither feel nor move his crushed legs beneath the gunship’s instrument panel. Hands shaking, the pilot lifted his helmet’s sun visor and saw the drying blood spattered across his flight suit. It belonged to Alyushin, his weapons system officer, who had been decapitated by his own gun sight on impact.

He closed his eyes, drifted and waited to die.

…please…tell me…these are not…

Images teased his brain. He could remember gliding over the jagged peaks east of ancient Kapisa and a golden dawn breaking above the snow-choked passes of Nuristan as he banked his helicopter gunship northward toward the distant border of the USSR. Was it just a dream? No. He remembered now. After ten bloody years, after 15,000 comrades zipped into body bags, the Limited Contingent Soviet 40th Army was finally withdrawing from Afghanistan. He was going home. To Leningrad. To his family.

But something had gone terribly wrong.

Sounds and images flashed like tracer rounds across the pilot’s closed eyes: the warm sodium glow of Bagram’s hangar, Alyushin’s crisp salute, Stas’ prescient warning, Yuriy’s duplicity as the eight commandos of Spetsgruppa Alfa loaded a dozen meter-long cases, each stenciled with a blatant lie, into his gunship’s cabin.

He remembered a strange key. Six latches. A bullet-shaped cylinder bearing a red star. An urgent plea to his commander…

Yuriy, please tell me these are not what I think they are.

…and Yuriy’s astonishing response…

Just get them to a safe place, Dmitry Mikhailovitch. For God’s sake!

The pilot heard himself praying now to that God in which he never believed. He prayed the Sukhoi Fencer flying high-altitude support would quickly follow protocol and destroy his disabled gunship before the döshman, the faceless “enemy” he had been killing for a decade, found him. Or his cargo of “meteorological equipment.”

As he waited for an Aphid missile to end his pain and absolve him of his guilt, the pilot struggled to pull the leather glove off his trembling right hand. Numb fingers fumbled to unzip the breast pocket of his jacket, search within and extract the engraved metal disk his flight mechanic had pressed into his palm before lift-off. He fisted it tightly, squeezed his eyes shut again and recalled Stas’ insistent voice.

Please, sir! Take it for your daughter.

The burnished silver heirloom calmed him like morphine as he watched himself from above, walking with a light, happy gait along Dekabristov, his long legs warming with the brisk movement. He could hear snow crunching beneath his civilian shoes, his footsteps tapping lightly on the granite stairway up to his flat and Maryna’s cry of anguished relief as the front door cracked open. He could feel the warmth within radiating toward him, inviting him into his wife’s welcoming embrace, her tears of joy wet on his cheek. He could almost taste her mouth as they kissed for the first time in over a year.

Pápa!

An excited voice warmed his ears as the little girl pattered barefoot across the polished wooden floor and flew into his open arms. How tall she had grown. He could feel his hand clutching Stas’ still-frozen gift in the pocket of his overcoat, the silver broach engraved with calligraphy that formed the shape of a proud lion looking back over its shoulder. He watched himself display the heirloom in his open palm like a glittering sweet as his daughter’s amber eyes widened with excitement.

The last thing the pilot’s imagination heard was Sonya’s delighted laughter in the wind as his dream of Leningrad faded into a lace of ice crystals on the shattered canopy above him.

ONE: THURSDAY, 2 JULY 2009 • CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

Summer heat caresses her skin as she crosses Garden Street into Cambridge Common. Bare-chested boys hurl softballs and toss Frisbees across its tree-lined green wedge in the muggy afternoon as girlfriends lounge on blankets by the barbecue. Sweat mingles with slow-burning charcoal, freshly cut grass and the promise of rain. Eight years dissolve.

Walking the Common’s shaded brick path and breathing in the humid, deciduous scent of her interrupted youth, Sonya Aronovsky feels almost relaxed. Here, the world still looks, smells and tastes exactly the way she wants to remember it: like rowdy boys in sleek boats cutting a wake up the Charles, like grilling burgers and cold beer, like Danny’s warm, salty skin after a race.

Here, there is nothing to remind Sonya of her real life.

Through Johnston Gate, Harvard Yard remains an academic anachronism. Clusters of visiting applicants still stroll the elm-shaded quadrangle of brick façades, slate roofs, and white steeples, regaled by student docents in veritas T-shirts. Still guarding the battlements of University Hall, a bronzed John Harvard slumps in ennui as kids polish the toe of his left shoe for luck with their scholarship applications. Pausing on the diagonal walkway, Sonya remembers how much she loved this indulgent ivory tower, and how much of her closed down when she had to leave its cloistered world of long-winded lectures and late-night liaisons for the hard realities of a life under constant siege.

Her leather knapsack is slung over one shoulder and the sleeveless linen blouse beneath it is glued to her body in the sticky heat. Sonya has dressed conservatively in a knee-length skirt, her short blonde hair brushed back off her forehead and only the bare essentials of make-up. She has spent most of her life hiding inconvenient emotions behind a fortress of cool professionalism, but at this moment, Sonya is unable to ignore the fluttering stomach that reminds her why she has come here.

Across Francis Street, Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of World Religions hides its Brutalist face from the Gothic disdain of Andover Hall beneath a green Ginkgo canopy as Sonya approaches the slatted gate, finds a number on the call box directory and punches it into a chrome keypad. The amplified voice that answers causes her face to flush. She pretends not to recognize its owner and buries her feelings along with everything else in the world she has ever loved.

“I have an appointment with Father Callan,” she announces.

“Back door,” Danny’s voice replies without a hint of emotion.

The gate buzzes open and Sonya places one Ferragamo sandal in front of the other, focuses on navigating the blacktop driveway as her pulse races. Even graduate students have abandoned the campus for the Independence Day weekend. The only sound she hears is the chirp of nesting robins. A footpath leads her to a pair of green doors beneath the bank of second story windows overlooking a lawn dotted with dogwood.

Sonya hears his footsteps even before the aluminum door clicks open. Her eyes touch first on his hand, its sinewy, suntanned skin feathered with golden hairs, and then on his wrist and the stainless-steel divers’ watch his mother had given him as a graduation gift. Despite Sonya’s resolve to remain detached and in control, Sonya cannot help but remember. Everything. When her eyes reach his face, she can almost feel his strong arms around her body again.

“Long time, Sonny.”

She smiles at the memories his nickname evokes and prays the flush in her face is not as transparent as it feels. He has to be almost forty by now, even more chiseled than she remembered him. His short, sandy hair is still as unkempt as it was on those autumn afternoons when he sculled the Charles River as if nothing else in the world mattered. But his sharp blue eyes are set deeper into a filigree of creases, not really laughter lines, more as if life has finally convinced him of its seriousness. For some reason, she expected him to be dressed in clerical black, a white Roman collar beneath his square jaw. Instead he wears a navy camp shirt, khaki cargo shorts and sandals, almost as if he wants to remind her of how it used to be.

“You look different,” he says. “I mean, good. More…” He seems embarrassed to be staring at her. “The short hair works for you.”

“Better in the heat.” She smiles awkwardly. “So, should I be calling you ‘Father’ now?”

“Only if you’re seeking pastoral counseling.”

“We’re safe, then.” Sonya brushes quickly past his curiosity. She can feel his eyes following her movements all the way up to the second-floor landing. “You’re teaching here permanently?”

“Since they gave me an office, I’m practically living here.”

Danny escorts her down a narrow hall where a faint odor of mildew rises from the carpet. “Inter-faith studies focused on Central Asia are not quite as popular as interpretive hip-hop in post-modern America, but my classes are always full. Students are particularly interested in Afghanistan. Go figure! Maybe a morbid curiosity about innocent people we’re bombing back to the Stone Age.”

“Yes, I was one of those students. Once upon a time.”

“As I recall.”

Danny’s shortened Bostonian vowels sound odd to her after an eight-year absence. In the Hebrew Reali School she attended as a child, Sonya was taught to speak “proper” English, instead of the harsh colloquial patter of settlers from Brooklyn. Her mother never lost her Russian accent, but Sonya could pass for a well-heeled Chelsea schoolgirl as easily as she could an American Millennial.

She enters Danny’s tiny office, a microcosm of his eclectic mind. All around the room, hundreds of books are arranged on his shelves by alphabetical category: anthropology, archeology, art history and so on. Between the shelves, he has hung a framed intaglio broadside of Saint Francis of Assisi’s prayer: Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace, and a brocaded Tibetan thangka depicting a blissful figure meditating on a lotus flower. He once told her it represented the quintessence of human compassion. Hanging in the only other free space on his wall, Sonya recognizes an Arabic calligraphic illumination of the opening salutation from Al-Qur’ân: In the Name of the One, the Compassionate, the Merciful…

The theme of Danny’s academic pursuits dovetail so seamlessly with his inspiration. Sonya cannot help but smile at his endearing naiveté, but she is happy to see he still allows himself one secular conceit: the 2004 Red Sox pennant hanging proudly above his desk.

Sonya drops her knapsack and sinks into a worn armchair. She watches Danny crack the seal on a tin of expensive tea and carefully spoon fragrant leaves into the basket of an iron Japanese pot. It is so like him, going out of his way and spending more than he should to accommodate her tastes. She feels uncomfortably self-conscious, considering the way she left things eight years ago.

“Needless to say,” he says anyway, “I was surprised by your letter. However, you really could have benefited from a Catholic school education in penmanship. And maybe even a good thrashing from one of our Sisters of Mercy.”

Sonya purses her lips and crosses her legs impatiently. “When you’ve finished my handwriting analysis, Father Callan, I’ll explain why I wrote that letter.”

Danny unplugs the hissing plastic kettle, pours boiling water into his teapot, settles into his creaking desk chair, and strains unsuccessfully to appear relaxed. “Forgive me, Sonny. I promised to listen to your story, not reopen old wounds.” He pours tea through a strainer into two cups bearing the Society of Jesus monogram. “Hope you still like Russian Caravan.”

“Horoshaya pamyet,” she suppresses a smile while appraising his inquisitive stare. “Good memory.”

“Your letter said something about a family heirloom?”

“Actually, something I found in my mother’s flat.”

“And how is Maryna these days?” Although he remembers her mother’s name, likely stores it in the same place he keeps historical minutia, Danny never met Maryna Aronovsky. And never will.

“She died three years ago.”

“Sorry.” He draws a breath and awkwardly shifts his emotional transmission into condolence gear. “I hope your mother finally found the peace she was looking for.”

Danny knew that Maryna had been a dedicated peace activist in Israel, much to Sonya’s chagrin. It had been so like her mother to redouble her efforts after Hezbollah began launching missiles from the Lebanese border in July 2006.

“Katyushas hit a hospital in Safed and killed a couple Arab kids in Nazareth,” she explains. “Mother was appalled that they would shoot at their own people, even if they were Israeli citizens. So, she went straightaway to the Galilee to patch up all the wounded in Nahariya.” Sonya lowers her eyes. “Hezbollah barraged the town and hit Kibbutz Sa’ar where Mother was based.”

Recoiling from the memory, she assesses his reaction. “Ironic way to find peace, wouldn’t you say?”

He says nothing.

“Couldn’t bring myself to pick through Mother’s flat after cremating what was left of her. So I had everything boxed up and put into storage. Last year, I moved back to Haifa and sorted through it all. In a shoebox where she kept my father’s letters, I found this.”

Sonya flips back the unbuckled flap of her knapsack and withdraws a short carbon fiber tube. She unscrews the cap and carefully extracts a mottled piece of vellum. Danny clears a space on his desk and she gingerly spreads the fragment out for him to examine. Rough-edged on three sides and cut cleanly across the bottom, faded sepia calligraphic strokes are inscribed in neat lines across its surface.

“Looks like a Persian Ta’liq script,” he says.

“Quoting an Arabic surah. But I can’t read what’s underneath.”

Danny bends toward the vellum in amazement. “A palimpsest?”

“Appears to be.” She lifts a manila envelope from her knapsack and unwinds the tie-string. “A colleague at the Technion had an analysis done using Multi-Spectral Imaging.” She extracts a sheaf of digital prints and hands them to Danny, explaining as he reads.

“He said MSI employs lens filtration to favor various wavelengths from infrared through the ultra-violet range, “Sonya says. “The images get converted into digital stacks with an algorithm that enhances characteristics unavailable to the red-green-blue spectrum of visible light.”

“Right. Separates the spectral signature of older ink embedded in the vellum from newer ink on its surface,” Danny confirms.

Sonya watches his face intently as he shuffles through a half-dozen gray-scale images showing portions of the under-text at various sizes and resolutions.

“These strokes look familiar,” he says, “but the surface text is creating too many gaps to read what’s underneath.”

Danny glances up at her, obviously intrigued. “We need to show this to Cyrus.”

“He specializes in forensics,” Danny explains as they walk west on Brattle Street. “Cyrus made a name for himself identifying stolen artifacts and forgeries.”

“You suspect this piece is a forgery?” Sonya asks.

“Didn’t say that. But Multi-Spectral Imaging has limitations, and Cyrus has connections. He consults with anonymous high rollers that buy and sell antiquities. I’m going to need some technical back-up to decipher the text underneath.”

Cyrus Narsai’s antebellum home in West Cambridge sits well back from the road on a manicured green lawn. A pair of arching maple trees frame its Greek Revival portico and white Ionic columns support a peaked pediment and gabled roof. Cyrus appears at his front door flanked by tall sidelight windows and Danny shakes his hand.

“Sorry to interrupt your work, but I thought you might want to meet a young lady with an old manuscript.”

“And that’s what I so love about you, Danny Boy,” Cyrus replies. “You exploit all my weaknesses at once without making me feel the least bit guilty.”

“Just remember to make an act of contrition, Cyrus.”

When Danny introduces Sonya, Cyrus’ silver-streaked Van Dyke shifts from laughter to lecherous grin. “We’re shoeless here,” he says, as Sonya feels his hand escort her into his vestibule. “These damn pine floorboards scratch if you breathe on them.”

Cyrus’ pristine flooring is finished in a dark stain that makes the white leather sectional seem to levitate in front of his ceramic fireplace. The décor is elegantly sparse: framed black and white Man Ray photographs hang from rails between shelves of hard-bound art books, antique Persian rugs protect the soft planking and a Chihuly blown glass sculpture on a black marble pedestal splashes primary colors onto the room’s otherwise neutral canvas.

When she slips off her shoes, Sonya stands eye-to-eye with Cyrus. Slender and fit, he has smooth olive skin and a shock of salt-and-pepper hair styled to look as if it has not been. Over faded jeans, he wears an unironed white linen shirt, sleeves rolled and the front placket open far enough to reveal an antique gold coin hanging in a trimmed thicket of silvery hair. As he pours iced ginger lemon tea into hand-blown glasses for his guests, Sonya unscrews her tube, carefully extracts the rolled vellum sheet and lays it on his glass coffee table.

Cyrus barely glances at the manuscript before launching into a lecture, clearly delighting in the sound of his own voice. “You can make parchment or vellum from any number of animal hides. Scribes preferred calf, sheep, or goat,” he explains, rubbing a thumb against two fingers. “The very best vellum, translucent and thin as a condom, always came from an unborn calf.”

Cyrus crinkles his hawkish nose and hands Sonya a frosty glass, taking the opportunity to appraise her figure. “Greek scribes liked goats because they were plentiful and, well, receptive, I guess.” His left eyebrow twitches. “One goat gives you two sheets. You rule out lines with a blunt point, then write your text with a reed pen using ink made from crushed oak galls."

Comments

Excellent writing style

This left me wanting to read more

Strong writing and such an…

Strong writing and such an interesting plot. Well done!

Strong Writing

You build up the tension well as the backstory and the new events appear to merge. Thumbs up!

Thanks to the judges

Many thanks to Robert, Ruth and Kelly for their kind comments on The Missing Peace. I am encouraged and humbled by their cudos!

All the best,

Tom