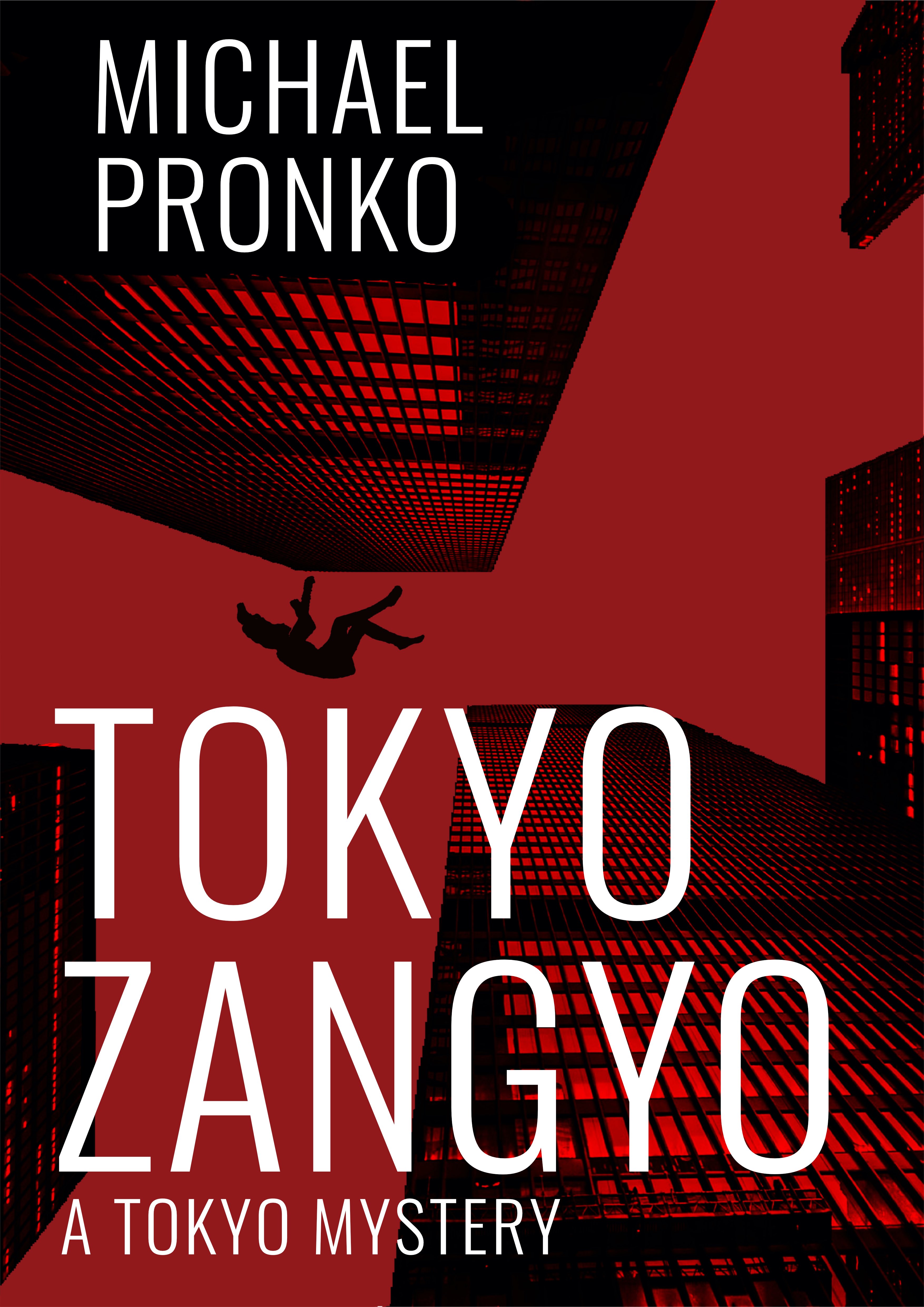

Tokyo Zangyo

by

Michael Pronko

月に村雲、花に嵐

Tsuki ni muragumo, hana ni arashi

The moon will be covered by clouds, flowers blown in a storm.

—Japanese saying

残業 Zangyo

Overtime work, often unpaid.

—Common Japanese word

Chapter 1

Shigeru Onizuka woke up shivering, naked, on the roof of his company building. His head spun from alcohol as he pulled himself up on the rooftop lunch table. He tottered but couldn’t walk. His feet were tied. He hopped, once, twice, toppled onto the bench and slapped his arms and chest to warm himself, his head swollen and throbbing. His body shrank from the cold and shivered harder as he tried to piece together how he’d gotten there.

He’d had whiskey at the bar and more later, and almost nothing to eat. He must have blacked out. That had happened before—too much booze to remember how he got home—but he’d never woken up naked, tied up, and confused on the roof of the company where he’d spent his entire career.

And he had never heard voices before. They echoed inside his head.

On the far side of the roof, the smoking area shimmered like a mirage. On one of the trees that ringed the area in tall planters, he saw a light-gray jinbei wraparound shirt and tie-up shorts, hanging from the branches. He staggered toward the meager summer clothes, remembering—vaguely—having pulled them on earlier. A pair of tatami sandals was set below.

Squinting against the spotlights that outlined the roof, he tried to see if he was alone. The wind roared past his ear, speaking its own language. The spotlights cast stripes of dark and light across the roof. Beyond, in all directions, the lights of Tokyo shimmered and danced with each doddering step. The imposing buildings of Marunouchi’s business district—the center of Japan’s economic engine—swayed and blurred. He had to sober up.

Onizuka untied his ankles, his fingers stiff and sore from the cold. He stood, placing one bare foot on cold concrete after the next, and moved toward his jinbei, something at least to cover himself with. He shivered and slapped his skin again, almost there.

He snatched the jinbei, bashing his shin on the tree planter. He pulled on the shirt and tried to tie the flap, but after a couple of tries, he left it. He raised his leg to get into the shorts and tumbled over. He got up, but had to stoop down to yank them on. He slipped his feet into the soft tatami sandals, relieving the pain from the icy concrete.

The shirt and shorts did little against the harsh wind blowing crosswise twenty stories high. The jinbei was summer-wear and his limbs and his chest wouldn’t stop shaking.

Where was his cellphone, money clip, and watch? He rubbed his wrists, raw from rope burns, remembering vaguely taking off the watch and putting it in the pocket of his wool pants. And where was his tailored suit and wool overcoat? He could feel his packet of Sobranie cigarettes in one pocket of the jinbei, a few still left.

He snatched at shards of memory, but nothing fitted into place. How did he get through the lobby? Did he come in through the parking lot? The service elevator? He remembered voices, women’s voices, mocking, accusing, commanding. Where did they go?

A woman’s voice whispered to him. “That way. Toward the lights.”

Onizuka steadied himself with a tree branch as he peered around the glass divider into the smoking area.

“That way,” the voice said again, clear and steady, a man’s voice now, far away, muffled.

He spun towards the voice, and looked around the smoking area, but along the trees and inside the partitioned space there was nothing and no one, except himself.

He patted the pockets of the jinbei for his lighter, an expensive present. Had he been robbed? Holding the wall, he reached for one of the communal lighters in the smoking lounge. He held himself up on the shelf where people rested their laptops to work through cigarette breaks.

“Towards the lights. Over there,” the man’s voice whispered.

Onizuka spun toward the voice, but there was nothing there. He stood and turned and turned again, stopping in the direction of the national gardens and palace moat opposite to where the business district hummed, still lit up in late-night mode. The expanse of the palace grounds was dark.

It was his voice, though. They’d competed since the first day at the company, gambling on the other’s tripping up and falling behind. But it had never happened—until now.

He twisted in the other direction and could see, dimly, hazily, lights on in buildings across the street. People must still be working. He twisted his wrist, feeling for his watch. He had no idea what time it could be, what day. It must be Monday morning. His appointment had been on Sunday, her busiest day.

“Toward the lights.” He heard the voice as clear and sharp as the wind. It was a woman’s voice now. The man’s voice had changed somehow, as if coming from inside his own head. The woman’s voice was there, too.

“Who’s there?” Onizuka tried to summon his commanding tone as a bucho section chief in the top media company in Japan. He was used to giving orders, not receiving them. He called out again, but his voice cracked and slurred, weaker than wind, softer than the voices in his head.

He pulled out one of his Sobranie cigarettes and fumbled with the cheap, shared lighter. He flicked and flicked until it caught the black paper. The smoke cleared his head for a moment before confusion swallowed him again. He pulled the thin shirt around himself and scanned the roof for the voice.

He stared at the picnic tables, used mostly by the OL office ladies and new recruits who didn’t bother lunching with managers, their promotion already stymied. He’d had those installed, and he sometimes ordered pizza for everyone when a contract was completed. He hated pizza.

“You know what you have to do, so do it.” The voice came again, strong and demanding. He turned toward the lights and the new fence.

He realized who it was.

It was her.

He’d heard her voice for a year afterwards, but gradually it had faded and he could hear himself think again. Now, she was back.

From behind, a shove sent him tumbling onto his knees. He swayed on all fours for a minute. His body felt hollowed out and depleted. Hoisting himself upright, he held out his arms for balance as he clawed his feet back into the sandals.

“Go on. From the same spot,” the voice insisted. Another shove sent him stumbling forward.

He wobbled away from the picnic tables and the smokers’ area toward the spotlights along the Marunouchi side. A huge gash, which looked like an upside-down V, was cut into the protective fence that lined the roof. He didn’t remember that V in the fence.

“You know the place. Right between those lights. Straight ahead.”

“What place?” Onizuka croaked, accepting the voice.

“There. Straight ahead. The same place.”

“I don’t—”

“You know where. You know why.”

The voice seemed closer, inside and outside his head, but he couldn’t see anyone.

He turned to look at the cut-open V. It was where she had stood, just before. He’d been there many times, stood there smoking and thinking. He would look over the edge of the roof and down at the wide sidewalks of the Marunouchi district twenty floors below, empty now of traffic and pedestrians.

He’d lost another bet, the biggest one. He didn’t need a voice to tell him that. He had a debt to pay, and he always paid his debts. That was how he’d kept winning. Standing around smoking only postponed payment.

“Keep going. You know what to do.” The voice was carried by the wind, mixing with it.

He might as well go. He heard more voices, a chorus now, his wrestling coach, that neighborhood policeman, his first boss at Senden, the guy he got betting tips from, all of them gone. The voices felt heavy and solid, joined together like arms pushing him, dragging him to the edge. He could no more resist the force of the voices than he could resist the force of gravity.

He staggered forward, all of them, all of it, behind him now.

He was so tired of the junior employees, the expenses, the bank transfers. He was tired of breaking in graduates from name schools, of drinking with contacts, golfing on Sundays. He was tired of the hassles with Human Resources, the endless meetings, reports, action plans, rule changes, mission statements, committees, presentations, the last train home.

He had never had a full night’s sleep since he started work. He was emptied out daily and never refilled. Emi helped him live with it, distracted him from it. Gambling gave him the thrill he remembered from his youth. But all else, everyone else, was a drain.

He was tired of the grudging promotions, the observance of hierarchy, the constant niggling demand for loyalty. The company would suffer in foreign places by losing the roots of its Japanese-ness. He helped them expand overseas, but he should have, and could have, buried them with what he knew.

Taking the position overseas wasn’t what he wanted. It was what he was ordered to do. That was his life, following orders, or guessing what the orders were and following through without even hearing them spoken.

He walked toward the fence and looked twenty floors down. The shape of the fence wire cut the city into small diamond sections. He patted his pockets for his cigarettes. He wanted one more.

He thought of his wife and his sons, but they had never been close. They were casualties of his success. His oldest son was at a good company, and his wife had money from her family, and all the winnings he’d left her. His youngest son had shaken free.

He would miss Emi, though, and her ministrations. It was only with her that he’d felt anything at all. Even anticipating the result of a big bet was never as good. He could hear her, feel her around him, inside him, next to him, her heat warming him even on the roof.

He flick-flick-flicked the cheap plastic lighter and lit a last cigarette. He tried to stop shivering by wrapping his fingers through the fence. The wind felt colder at the edge and the lights brighter. He squinted as the strong light floated up like water from below and rose and fell into the distant sprawl and swell of the city. The fence was like one around a swimming pool, keeping him from entering.

He moved down the fence hand by hand until he came to the huge V, the only way to get to the light-water, to the city. The V in the fence was big enough to get through. He took another drag on his cigarette, held it up against the panoramic view below, almost done.

He stepped out of the sandals and positioned them neatly together, facing the edge, in the same place she had. His body shivered uncontrollably. His feet felt numb, making it hard to walk. He would swim instead.

He grabbed the fence with both hands and ducked through the cut-open V. He could see better there, the whole city before him.

It was easier than he thought.

He heard a shout behind him, but he tuned it out. He didn’t need to pretend to listen anymore.

The voices faded as he stepped onto the outer ledge, balancing himself with a hand on the fence, listening to the wind.

He took a last puff and tossed the half-finished cigarette aside.

Tokyo flowed in all directions like an ocean of light. He was ready to dive in, to return. He’d swim over to Tokyo Station, its squat, quaint brick front waiting for him. He’d been through there twice a day since college, and loved the fierce power of the place. He’d swim to that energy, tap it, and from there, decide where to swim next.

He took a step forward, felt the edge with his toes, and breathed in deeply. He heard the fence rattling behind him and voices shouting, babbling.

He straightened his jinbei, sober enough at last to tie a knot to hold the shirt in place. Then he cleared his throat and dove into the light.

Chapter 2

Detective Hiroshi Shimizu reached for his buzzing cellphone, a victory of habit over fatigue. He flipped his legs over the edge of the bed and listened to explanations and directions, and then orders, from Detective Sakaguchi, head of homicide.

Half listening to Sakaguchi and half-asleep, Hiroshi looked at Ayana’s long black hair draped over her pillow. Hiroshi ran his hand along the curve of her body from her shoulder to her hip, giving her butt a squeeze, soft enough to let her keep sleeping, firm enough to rouse her if she was half-awake. He loved the way she made love sleepy, humming, flushed, opening to it gradually.

She didn’t stir, so better to let her sleep. She’d been working late at the archives every night the past couple of weeks, a massive reshelving project that left her exhausted. For weeks, she’d come home and flung herself on the sofa, skipping kendo practice. Neither of them had cooked for weeks. They’d ordered out or Hiroshi microwaved something.

Hiroshi eased himself up and struggled into some clothes as quietly as he could. In the kitchen, he dug into a bag of chocolate croissants. He stuffed one in his mouth, dropped an apple in his pocket and left the bag out for Ayana, the top rolled tight.

When he got out of the taxi across from Tokyo Station, Hiroshi followed the glow of the LED balloon lights that lit up the crime scene. He walked past two coffee shops, both disappointingly closed. Ahead, blocking all traffic, tarps were stretched across the street and sidewalks. He gave up on the coffee and headed toward the lights.

Hiroshi flipped his badge to the officer at the entrance and looked for Sakaguchi. He stood a head taller and much wider than everyone else on the force, so was always easy to find. Sakaguchi signed a form and started to limp toward Hiroshi. As a former sumo wrestler, Sakaguchi had always seemed immune to pain, and to fatigue. He’d grown up in the poor part of Osaka, where work was the backbone of the day and complaints were left unspoken.

“Your leg all right?” Hiroshi asked.

Sakaguchi stood rebalancing himself, letting the weight down slowly on his knee. “Doctor recommends surgery.”

“Take time off,” Hiroshi said.

“I would, but now there’s this.” Sakaguchi leaned over to reset his knee brace.

Hiroshi wondered where he’d found one big enough for his tree trunk of a leg. He knew Sakaguchi could only find clothes and shoes at the one super men’s size shop in Tokyo.

Sakaguchi straightened up to take a clipboard from a young detective, scanned the form and signed it. Sakaguchi’s injury occurred when he stepped wrong chasing a suspect. It compounded the injury that had sidelined him from sumo years ago, but which had led him to take the police exam in Tokyo. This injury, though, looked like it would result only in surgery.

Hiroshi looked at the medical examiners working on the sidewalk. Takamatsu, his senpai and erstwhile mentor, was kneeling over the body and surveying every mangled bit.

The body was a tangle of limbs, one leg crossed backward, the other underneath, one arm flopped to the side and the other, undamaged, angled eerily upward as if pushing to rise from the street. The rest of the body and head was clumped across the sidewalk like wet red clay. Takamatsu was inured to every grisly detail. At every murder scene, Hiroshi looked away, but Takamatsu looked closer. Takamatsu had been a family friend, Hiroshi wasn’t sure of the exact connection, and had been the one to get him the position in homicide in charge of white-collar cases, overseas-related issues, and anything involving English. He was dragged into cases like this one, though, when he couldn’t find a good enough excuse to work from his office.

“Gives you renewed respect for gravity.” Sakaguchi looked up at the top of the building. “The windows don’t open.”

“Who called it in?” Hiroshi squinted against the lights.

“Some tourists from Indonesia.”

“Ruined their vacation.”

Sakaguchi said, “You want to get started on the roof? I’ll send Takamatsu up when he’s done down here.”

Hiroshi headed through the markers next to splattered bits of the body. He didn’t look down until he got to the entrance and hurried inside.

Above the lobby a huge sign announced the name of the company—Senden Central. Long, vertical banners stretched from ceiling to floor with city scenes of New York, London, and Singapore. Slogans cascaded down inside speech bubbles from the toothy smiles of female models: “Now Senden Infinity,” “Going Global,” “From Tokyo to the World,” “Bringing People Together.” The banners curved like bows tied over the well-wrapped image the company had of itself.

On a chair in the corner, a gray-haired security guard sat rubbing his head and staring at the floor. A young officer from the nearby police box held open the elevator door for Hiroshi and reached in to press the button for the roof.

Comments

I got a real sense of place…

I got a real sense of place in this story. Your descriptions were vivid and teased me information so that I could see a very clear picture of the setting.

Insightful

When Shigeru Onizuka was on the roof, trying to decipher what was going on and what to do, I could really feel his thought processes and confusion. Well done!

Intriguing

I love this as an opening to a suspense story. It's well written, it drew me in, and it has me intrigued and wanting to read on. Mission accomplished!