Bury Him: A Memoir of the Viet Nam War

Copyright 2019 by Doug Chamberlain.

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other – except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the author.

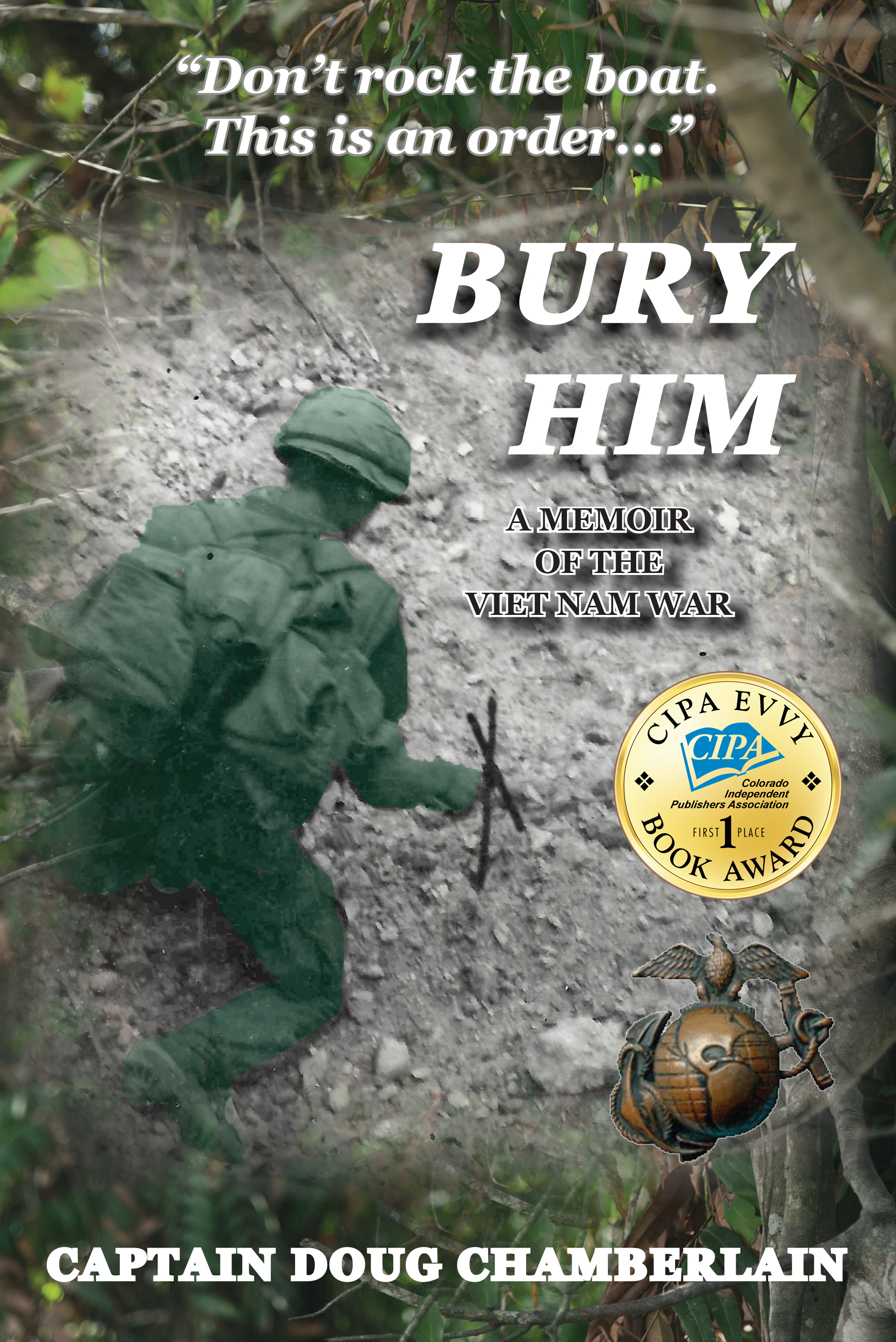

The front cover photograph of Marine Corporal Joseph T. Wnukowski was furnished courtesy of Corporal Wnukowski and Marine Corporal Joseph W. Freda, who took the picture.

Love the West Publications

Publishing Services by BookCrafters, Parker, Colorado. www.bookcrafters.net

…THE SEATS TO DENVER BRONCO FOOTBALL GAMES have been sold out for so many years that no one can remember when they weren’t. I have been a season ticket holder since the late 1990s. This particular Sunday afternoon was no exception. Over 76,000 Bronco fans rose to their feet at the Sports Authority Field at Mile High. They stood to honor the American and organizational flags being carried by the Color Guards entering the stadium through the north end zone. The United States Air Force, the United States Army, the United States Coast Guard, The Denver Fire Fighters, The United States Marine Corps, The United States Navy, and the Denver Police Department were all represented. The small contingents moved briskly to the yard markers on the east side of the field to which they were assigned, pivoted to their right, and then more deliberately and ceremoniously followed their yard line across the field. They stopped in a parallel line near the boundary line facing the sea of humanity standing in the west side of the stadium. The Marine Corps Color Guard was standing on the 50-yard line. In the usual sequence, the Stadium Announcer introduced the contingents beginning in order from the north end of the stadium. The roar of the crowd followed each introduction. I heard him say, “The United States Marine Corps”... and the sounds from the stadium began to fade away from me. I felt an overwhelming, smothering wave of shame that seemed to crush my chest and I thought my head was going to explode. Suddenly, I was standing alone in a bomb crater in the jungles of South Viet Nam. I was looking down at the partially decomposed remains of a Marine that appeared to have been abandoned and left behind. I felt myself shaking, and someone was approaching me with their hand out…and when they touched my left arm, I froze. I quickly looked at the person and soon realized it was a woman standing beside me who had purchased the Bronco game ticket for the seat next to mine. She was rubbing my arm and appeared to be looking at me with concern and compassion, but she said nothing. I had no idea who she was before the game, and I never had the opportunity to see her again after that day...

Preface

THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS is, and has been, the finest military force the world has ever known. One of the reasons is because of the esprit de corps that is created in those who serve in the capacity of being a United States Marine. The sacrifices endured in the training, and the expectations of those who have earned the title “Marine,” sometimes transcend the understanding of those who have never “been there and done that.” Most of the finest people I have ever known, and with whom I have been associated with, are United States Marines. The circumstances under which we became known to each other could play a part in my evaluation of these great Americans, but I have compared them to the standards of the hundreds of people I have known in public service and the business ventures in my life, and my dedication to these Marines has only been reinforced. With that said, any organization, team, or military branch is only as strong as its weakest member. There are always some in any common entity that fail to meet the standards of the larger group, and the results can be devastating, but not necessarily fatal overall.

Many of the names of the people in this book are individuals I was associated with once I arrived in South Viet Nam. Some of the names are fictitious to protect the identity and privacy of the individuals, and their families. However, the exceptions are Sergeant John “Jack” Johann; Lieutenant Caesar “Sid” Stair, III; Corporal Donald “Cathi” Catherall; Lance Corporal Gabriel “Gabe” Quinonez; Staff Sergeant Lutu; Lieutenant Jimmie R. Pippen; Corporal Joseph W. Freda; Corporal Joseph T. Wnukowski; Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mueller; and Lieutenant Colonel John R. Love, who was deceased in 2010. In addition, Captain Lyle Johnson’s name is listed as Killed In Action in Viet Nam in public documents. The other names in the military records after my Forensic Investigation was initiated are as they appear in those documents.

I could not have performed my duties as the Commander of Echo Company, Second Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, First Division of the United States Marine Corps with any kind of success if it had not been for the very courageous, professional, dedicated, patriotic, outstanding Marines in Echo Company, Second Battalion, Seventh Marines. My debt of gratitude to them can never be repaid. The word “hero” has been attributed to many in our society today. However, the word has special meaning to me when it is used in reference to anyone who has risked their own life and personal safety for the assistance to, and the defense of, the well-being, safety, and lives of others.

In my particular case, the Marines who served under my command of Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines will always be my heroes, and I will never forget the sacrifices we endured. As you read my accounts of the things I saw through my eyes, please keep in mind that every good and successful thing that happened to Echo Company while it was under my command was as a result of the never-ending support and efforts by all of us to make our unit succeed. I have intentionally left out many of the details of their individual work, in most cases, because I do not believe I can accurately describe the heroic efforts of my men or relate what they were thinking throughout our time together. I can only describe what I saw, and this book is my attempt to articulate the reasoning behind the decisions I made. After enormous thought and years of personal deliberation, this is my attempt to put into words what I recall during this period of my life from my perspective.

One perspective of my writing needs to be clarified as it relates to using the term “gook” in reference to the enemy forces in South Viet Nam. The term is used in a majoritive sense in the historical context of this writing. It also appears to have been used in the Korean War by American troops as nomenclature to reference the enemy. I fully understand that it can be considered to be an ethnic slur in today’s interpretation, but that is not what is intended in this book. The term is only used as a historical reference to the terminology that was used by American forces during the Viet Nam War. We also referred to those in that same general group as “Charlie.” In a similar manner, I include the use of the terms “baby killers,” “murderers,” “rapists,” and Marine “dogs” that were used by our Vietnamese enemies and the anti-war activists in the United States and around the world to describe our American Military personnel during that time. I would appreciate the tolerance and latitude by you, the reader, to allow me to preserve the historical accuracy of my book in this manner.

The final impetus for me to commit myself to the effort necessary to write this book came as a result of a conversation I had with Dr. Brent Kaufman, DVN, in 2015. Dr. Kaufman is the co-owner of the Goshen Veterinary Clinic in Torrington, Wyoming. He was a student of mine when I taught at La Grange High School in La Grange, Wyoming, after my release from active duty and following my first attempt to study jurisprudence at the University of Wyoming. I was also his basketball coach during those years at LaGrange. On the day of the conversation, Dr. Kaufman was administering medical treatment to one of my cattle, and he and I were jokingly reminiscing about those days at LGHS when he suddenly became serious. He said he had always wondered why I always seemed “mad and angry” during those years. That was the first time that I could ever remember anyone asking me about my behavior during that period of my life who thought it was abnormal, without being judgmental. He was not comparing me and my conduct to what and who I was prior to my military service, because he did not know me then. He was simply making an observation. His comment haunted me for several months, and it eventually led to the writing of this book.

Introduction

MY “ROOTS” ARE NEAR THE EDGE of the eastern Rocky Mountains in southeastern Wyoming and western Nebraska. My fraternal grandfather came to southeast Wyoming from northeast Indiana to live with relatives in the late 1800’s and to seek natural relief from the effects of tuberculosis, according to family historical accounts. It was while he was here that he homesteaded property east of what is now the town of La Grange. Family records indicate that my father and his four siblings were born on the homestead property. My father was born in 1909. Our family records indicate that the actual occupying of the Chamberlain homestead property began prior to 1900. The actual ownership document was called a “Patent” that could be obtained from the federal government after residing on a 160-acre parcel of land continuously for at least 10 years. Additional land was added to the original 160-acre parcel and I still live on that original homestead.

My mother was born in 1912 on one of the Warner homestead farms in extreme western Nebraska approximately 10 miles east of where my father was born on the homestead in Wyoming. My maternal grandparents were descendants of a large, extended family that emigrated from Sweden. The first historical record of the family involved Andrew Warner in Newtowne, Massachusetts, which later became the city of Cambridge. At what appears to be the first record of a town meeting held on December 24, 1632, he was given the responsibility of building “20 rods” of fence “to enclose the common,” a task similar to that assigned to many other settlers in Newtowne.

As we say in rural Wyoming and Nebraska where I was born and raised, “my roots go way back and are very deep.” Both of my parents’ families were poor by any standard, but both families survived by knowing how to be good stewards of the land, excellent practitioners of animal husbandry, and most of all, being great friends and neighbors.

I am the youngest of five children, and I was born in 1942. I had two Great-Uncles who served in the United States Army in World War I, and both were physically and/or emotionally disabled to some degree as a result of their service. One was my Great-Uncle Roy Hamilton, who was from my mother’s side of the family. He related to me that he had spent 43 continuous days in the trenches that were tactically used during his service in his infantry unit. “Uncle Roy” was plagued by continual “twitching” in his shoulders and torso, and he continuously tugged lightly at his clothing. My Great-Aunt Alice, his wife, said he had been like that since returning from “the War.” However, he lived until he was 90, and she lived to the “ripe old age” of 102.

My other relative who served in WWI was my Great-Uncle Guy Hanna, who also served in the United States Army Infantry as a Scout. He was from my father’s side of the family. He returned with severe damage to his lungs from exposure to mustard gas, and he had overwhelming emotional problems as a result of his service. Family memories of him were that loud noises would make him very nervous, and for several years, when an airplane would fly over, he would dive onto the ground, cover his head with his arms and hands, and shout warnings for everyone to “get down.” My siblings who remember him said that he was very withdrawn, and that he would often sit in a darkened corner of a room by himself. They reminisced that his behavior was so abnormal that some of their teenage friends were afraid of him. He was born 50 years to the day before I was. A bunkhouse where he lived near my grandparent’s home after his return from “the War” is still standing here on the homestead, although it is in a very serious state of deterioration. I have resolved to myself to try to preserve it, but I have never had the resources to be able to do it to this point in my life.

I had an Uncle Oris Chamberlain, who served in the United States Army in World War II in a Construction Battalion, and whose son, my first cousin, Oris Chamberlain, Jr., served in the United States Army Infantry in the Korean War. Junior, as we called him, was seriously wounded shortly after his arrival in Korea, and he bore the physical disabilities associated with those injuries for the remainder of his life. He recalled that when he finally regained consciousness after being hit by rounds fired from a machinegun, someone had removed his boots and taken them for their use because they thought he was dead.

My brother, Earl W. Chamberlain, served in the United States Army after completion of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) Program and his graduation from the University of Wyoming in 1954. He was stationed in Germany for a period of time during part of the “Cold War Era.”

Growing up in rural Wyoming was a “storybook” life. My parents created our sustenance by farming and ranching. We never went to bed hungry, but there were meals every day that were the creation of a mother who was very inventive and an excellent cook. There were few people, if any, that could be considered wealthy near the town of La Grange, the population of which was approximately 150 people. My education was obtained in a school system where there were only 30 students in the high school. My graduating class consisted of 10 young Americans, the largest class in the history of the school up until that time. We were taught that we could contribute to the land of the free and the home of the brave. It was instilled in us that we should try to make a better life “for ourselves and those whose happiness depended upon us,” which was part of our Future Farmers of America (FFA) youth organization pledge. My childhood was one where respect for others and dependency on others for survival were an important key to the military leadership that would be required of me later in life, even though I could not imagine it at the time.

From this small school and town in Wyoming over a four-year period came four state basketball championship teams in a row, four college athletes, one NCAA basketball coach, one banker and financier, two military Officers who served in Viet Nam, one Enlisted military personnel who also served in Viet Nam, some ranchers, some teachers, and some business owners, just to name a few of the accomplishments of our small group of students.

We did not have kindergarten in our small school, so some of us entered school when we were five years old. Our inspiration for learning began with Martha Ann Adams, our first and second grade teacher, who was one of the kindest persons I have ever known. My inspiration to become a pilot began with the boundless efforts of my third and fourth grade teacher, Shirley Mills. She was an unmarried teacher in a small town in Wyoming and was what adult males in our little town considered a “Knockout.” At our young age, we thought all of our teachers were beautiful, but what made Miss Mills particularly outstanding was her ability to relate to us and make us believe in ourselves, even if we wanted to be a pilot. She taught us all of the very simple fundamentals of flight. I eventually became a private pilot and had the tremendous pleasure of having her fly with me from Wyoming to southern California for an educational convention some 20 years later. We learned vocal music from Janette Kessler, a wonderful, but firm, Vocal Music Teacher who inspired us to love music and taught us how concentrated effort was essential to succeed in life. She was a fabulous mother, a great ranching partner with her husband, and an outstanding role model to all of us. Cleo Wheeland was a traveling maestro who came to our school twice a week and taught us instrumental music so some of us could play in the school band. Marching and playing in county fair parades were summer activities that he always demanded of us. Two coaches, Bill Perich and Ron Schliske, taught us the fundamentals of basketball. At the same time, they taught us the life lessons of self-discipline, personal sacrifice, and competing to win fairly while respecting our opponents. They required us to condition ourselves to develop endurance and instilled in us the courage to never quit, regardless of the difficulties we faced. Because of the teaching, training and inspiration of two high school Vocational Agriculture Teachers and Future Farmers of America Advisors, Marvin Riley and Jack Lester, I was elected to be the State President of the Wyoming Future Farmers of America during my senior year in high school. I was awarded an American Farmer Degree because of the efforts of these kinds of great people that played such an important part in shaping my life during my childhood and adolescent years. Little did I realize at the time that the lessons they taught us would play a key role in the discipline required in my future military experience.