1. Transistor Radio (title of first short story)

They’ve conquered our town and hoisted their flags at different locations. They sing songs of victory every morning during their parade and send fear coursing through our veins. We’re stuck in a small church with a priest who assures us daily that the military will reoccupy the town and send the Boko Haram insurgents to their graves. He doesn’t seem too sure about the details of the reoccupation but Father Romanus, a square-jawed, light-skinned energetic man with shocks of gray hair, feels the need to keep our hopes alive. What else can a sixty-year-old priest do in the midst of three teenagers who are terrified by what their eyes have seen?

We were woken by the sounds of gunshots and bombs in the middle of the night when our town was conquered. The insurgents had set houses on fire and shot at occupants who attempted to escape. My parents and I had managed to avoid being burnt alive by dashing out of the house before it was set ablaze. But when we joined the crowd of people scampering for safety, my father lost his grip on me and I ended up in the middle of a mad rush for survival.

Bullets pierced the hearts of men and women and children, and the voice in my head kept urging me to keep running, lest I join those whom the earth had clasped in its embrace. So I kept running as fast as my legs could carry me and only stopped running after getting into this church where Kabiru and Maryam were already seeking refuge. Father Romanus locked the iron entrance door when he saw that no one else ran inside for protection. With my eyes fixed on the door, I silently prayed that my parents would knock from outside and whisper my name. But I heard no knock or whisper, only the deafening sound of gunshots from bloodthirsty fighters celebrating their victory.

Through Father Romanus’s transistor radio, we’re being informed of the federal government’s efforts in sending the insurgents away from our land. But the invaders are getting stronger by the day. Every morning when we wake up, we look forward to hearing the sounds of victory from our own troops but the insurgents remind us that they’re in charge here and we’ve had to embrace this reality; we have no choice.

Yesterday, Father Romanus condemned the idea of One Nigeria and saluted Nnamdi Kanu for the campaign he’s leading in the southeast. I remember my father raining curses on Kanu and accusing him of leading people to their deaths. My English teacher, Mr Abdullahi, says Kanu is an opportunist feeding on the gullibility of his followers. I tell the priest about Mr Abdullahi’s comment but he says nothing and only concentrates on the tiny female voice broadcasting the evening news on the radio. Her voice has a soothing reassurance that all will be well soon but it tastes like bile when she says a military jet has been blown up by the fighters, killing three officers. Dejection reads on the priest’s face. Then he looks up and says ‘Your English teacher is Hausa. I don’t expect him to say anything different.’ Then he goes back to listening to the radio.

Father Romanus is crushed by all the sad news around us and buries his face in his palms. An airstrike could have liberated us but the insurgents have averted it. Our freedom is uncertain and I realise that I may never achieve my dreams of becoming a soldier and marrying Maryam. Maryam, a tall girl with dark brown skin, is Alhaji Hassan’s daughter and the most beautiful girl in my class.

Maryam is unaware that she’s part of my dreams even though we’re best of friends. At sixteen, I’m not confident enough to express my feelings to her. Could it be fate that has brought us under the same roof when death could knock on that iron door the next minute? But if death walks in and decides to take us all, I hope it gives me the privilege of holding hands with Maryam just before I cease to breathe. Only then will I rest in peace.

We’re hungry and can’t withstand the hunger that, after three days, no longer has any shame in the midst of this chaos. We’ve exhausted the chin chin and drinks in Father Romanus’s office. He said that Sister Rebecca, the choir mistress, had brought them for the kids and was going to share them on Sunday. If Sister Rebecca is still alive, she wouldn’t know that she had saved the lives of her priest and of three teenagers who weren’t brave enough to venture into the church farm in the third compound to pluck fruits. We still have to choose between cowardice and bravery. We either stay locked up behind these walls for goodness knows how many more days and die of hunger or get into the third compound and help ourselves.

The only time we dared to open the door was last night when we all ventured outside to empty our bowels. I had imagined death jubilating at our foolishness in walking right into its arms when it had been patiently waiting for the right time to knock on our door and strike. The smell of my shit chased the thought away. And when we got back inside to sleep, it wasn’t death that appeared but my parents. My silent prayer had been answered and they both held my hands and took me to a place they deemed safe.

‘The church is not safe for you, Musa. You’ll be safe here in your grandfather’s house.’

I was woken by the sound of gunshots as the insurgents began their morning patrol. Father Romanus is now used to these reverberating sounds. We’re not and he pities us when we jump from our mat like mice being chased out of a hole.

Then he’ll whisper:

‘God of Elijah, show mercy upon your land.’

Kabiru volunteers to go pluck the fruits and I see from Maryam’s face that she’s impressed with his bravery. Added to his bravery is his masculinity and height, the features that make a girl drool. Until now Maryam has proved to be an exception and hasn’t shown any signs of liking him.

Perhaps she likes guys like me who are closer to the ground. Does anyone ever admit to liking short guys? I’ll ask Maryam what her spec is, if we get out of here alive.

‘I’ll go with Kabiru.’

‘It’s not safe out there for you kids,’ Father Romanus says, in a tone laden with fear. ‘I’ll go instead while you all stay here inside.’ He’s not a man to sit back all cowardly, watching teen boys risking their lives in order to survive.

Father Romanus gazes at the crucifix on the altar as though he’s expecting approval from Jesus for his daring task. There’s an unspoken desire in his eyes and I figure that he wants Christ to perform an instant miracle and set our land free. The priest leaves us standing on the aisle and walks to the altar. There’s a possibility of running into gun-wielding insurgents on the street. He wouldn’t venture out without getting fortified, so he kneels before the crucifix for a silent prayer.

Sometimes when we peep through the window, we are able to catch a glimpse of the insurgents patrolling the town with guns and grenades strapped around their bodies. But the street seems deserted today and I wonder if it isn’t famished and waiting for someone new to devour. The priest? Fear grips me impulsively.

‘Father Romanus, please don’t go,’ I say, ‘The insurgents usually patrol in the morning, afternoon, and evening. But they’ve only had their morning patrol today and it’s already 4 pm. I have a bad feeling about this.’

Maryam and Kabiru stare at each other before giving me a probing look. Father Romanus smiles and fumbles in his pocket for the farm keys.

‘Nothing will happen to me, my son. Get me the bucket from my office.’ If he doesn’t return, Maryam and Kabiru will tell the story of how I got him a bucket to fetch the fruits.

‘No, Father Romanus. Please don’t leave the premises. I know what I’m saying.’

‘Maryam, please get me the bucket from my office.’

Father Romanus has been gone for fifty minutes. My bad feeling doesn’t leave me and I know I’ll be broken if something happens to him. I imagine a bullet ripping his heart apart. I close my eyes to send the thought away but this time I see the priest’s head being chopped off by Yusuf Shekau himself and hear him letting out a raucous laugh as he sends the head rolling.

‘Auzubillah!’ I scream.

‘What’s happened?’ Kabiru asks.

‘What’s wrong, Musa?’ Maryam moves closer to hold my hands and reassure me that the priest will return to us safely. She looks at the tears hanging wet in my eyes and embraces me warmly. We’ve never hugged until now and it feels as though I’ve been taken to paradise. She smells like bubblegum and I resist the urge to run my fingers through her cornrows. I shut my eyes and let my anxiety fly away.

It’s more than four hours since Father Romanus left. My worries are becoming more intense and this time around, Maryam and Kabiru are also getting worked up. The insurgents are blood-crazed and if Father Romanus gets into their hands, we’ll be discovered and we’ll suffer the same fate as him. I try to hold onto the hope that our own deaths may somehow be less cruel because we’re kids. But Muslim kids seeking refuge in a church? ‘Infidels!’ they may yell, before spraying us with bullets.

Kabiru paces around the auditorium and suggests we pray for the priest’s safe return. The three of us hold hands and I walk them to the crucifix.

‘Jesus, please, let Father Romanus return safely.’ I see the shock on their faces but they say nothing and I offer no explanation for why I’m calling on Jesus instead of Allah.

Wouldn’t the world tell us how selfish we were to allow a harmless priest to walk into his own death because we couldn’t endure hunger? The headlines will read: ‘Catholic Priest Killed by Boko Haram Insurgents after Trying to Get Fruits for Muslim Kids Seeking Refuge in His Church’. The world will only blame us if we get out of here alive.

The thought of my own death brings back memories of Manga, the old soldier who loved feeding us with tales of the civil war and how he survived it despite, according to him, dying for three days after being captured by the Biafran soldiers.

Manga’s tales held us spellbound and we always looked forward to hearing them. Often he spat in the middle of his stories and a curse intended for the Biafran commander flew out of his mouth. Even though our parents had debunked all his claims about his exploits in the civil war, Manga ensured that every story he told registered with us. Whenever he paused to let the stories sink in, he would shake his head and smile, revealing his few remaining bitter kola-stained teeth that managed to survive the war.

‘When Ojukwu captured me, he ordered his men to bury me alive, since their bullets hadn’t penetrated my skin, and you know what I told him?’ Manga smirked, waiting for us to chorus the response.

‘No, Manga.’

‘I told him I would come for him and rip off his heart.’

Manga’s response to Ojukwu sent shivers down our spines and thrilled us as he prepared for the sweetest part of the tale. Of Manga’s many tales this was one of our favourites, and its punchline made us deaf to all other sounds around us. Nothing else mattered to us, only this old soldier’s vibrant voice slicing through the thickness of the night’s silence.

‘So I was buried alive by Ojukwu’s men. By the time I rose from the dead, the war was over and Ojukwu had fled the country.’

Our resounding applause travelled through the town and we chanted Manga’s name in celebration of his victory against death. And this must have been the reason why our parents envied him and discredited his war exploits. Manga was a warrior.

We listen to the sound of crickets and our heartbeats, and to the protests in our stomachs, as we await the reappearance of the priest. I feel awful that I’m still famished, despite Father Romanus’s disappearance.

‘Stop there!’ The voice is brash and echoes through the four corners of the nave. We’re already on the floor and our hearts thud against the tiles. Someone’s leg is on my shoulder and I suspect it’s Maryam’s. She lets out a muffled cry and jerks the leg against my back.

‘Who are you?’ a distant voice says and I place Maryam’s leg on the floor, then lift up my head to see tiny dots of light shining in through the window. Kabiru follows suit. Maryam is shaking like a jellyfish and there’s a pool of pee between her splayed-out legs, soaking her long skirt.

‘Where are you going?’ the brash voice reverberates again but we’re already on our feet, peeping through the window. A truck and a bus are directing their full beams on Father Romanus. The moment I feared is finally playing out except that Yusuf Shekau is not here with the insurgents. He’s cutting off heads and laughing elsewhere.

Father Romanus says nothing but drops the bucket of fruits on the ground as gun-wielding men alight from the vehicles, one after the other. They surround him.

‘Are you deaf?’ The priest’s face receives a slap and three of the men hit him with the butts of their guns and watch him crash into a puddle before emptying their barrels into his tiny body. The transistor radio in his palm drowns in the puddle and the flicker of hope in his eyes disappears as the wind takes his soul away.

Comments

Great start

I quite enjoyed this! It isn't a happy-happy story, but it's good nonetheless!

Lagosian writer makes his mark

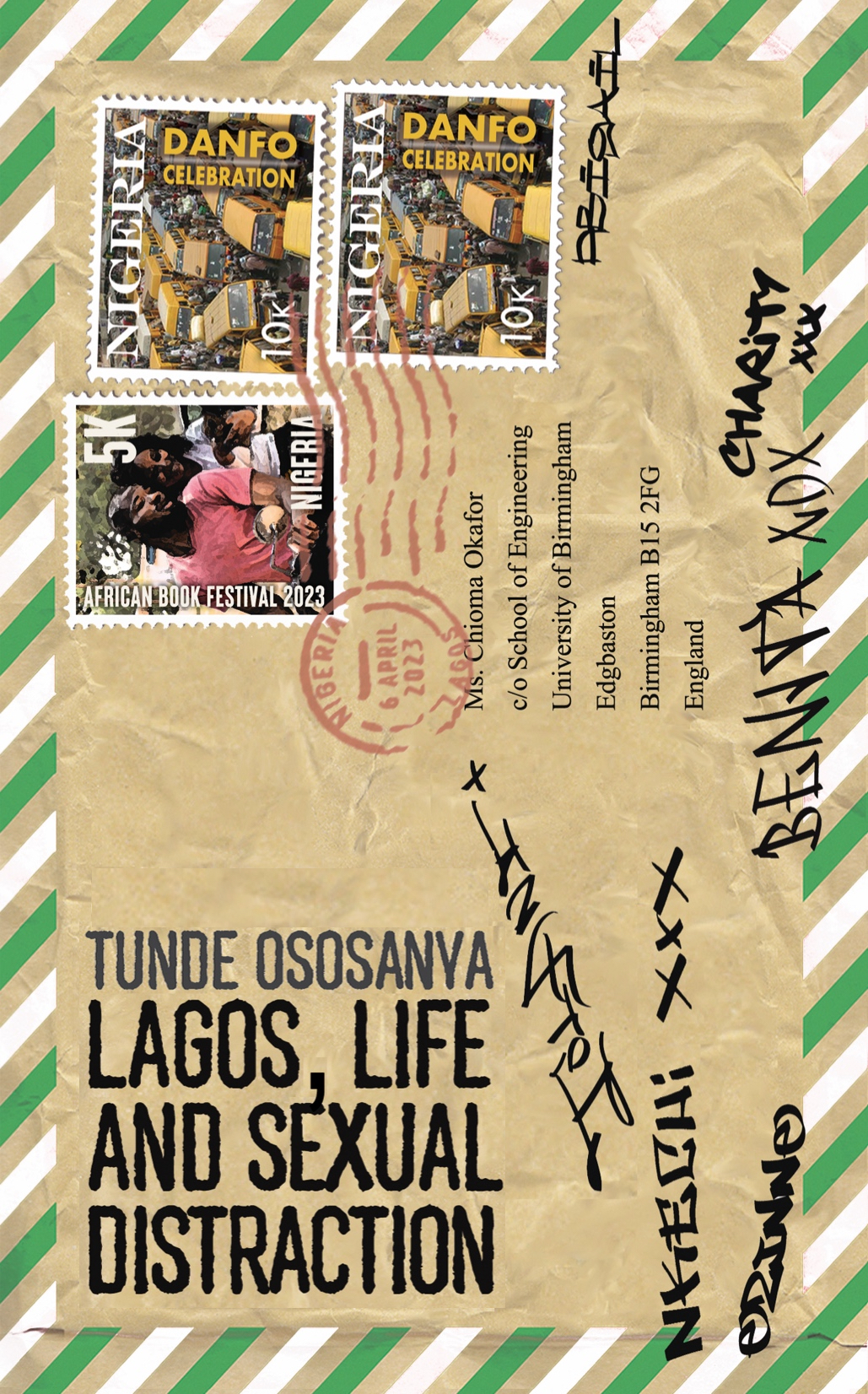

A well-deserved win by an aspiring new talent. Tunde Ososanya's collection of short stories, LAGOS, LIFE AND SEXUAL DISTRACTION, looks at the distinct character of life in Lagos—the commercial capital of Nigeria.

The book shows the tensions that exist between the generations, between the sexes and between different social classes and ethnicities.

Two stories are dedicated to the plight of the mostly Hausa and Muslim people living in northern Nigeria.

Most of the stories, however, deal with life in the south as experience by the mostly Christian and Yoruba or Igbo people. It shows what a typical Lagosian goes through in order to survive, and why people who’ve lived in Lagos are able to withstand the harsh realities they experience in other parts of the world.

According to the author, every Lagosian is expected to live by the popular local saying, “Shine Your Eyes”, meaning you've got to be vigilant.

Lagos is a land of opportunity, says the author, and Lagosians are one of the most successful people in the world by virtue of their perseverance. As the author says, “I dey live and work for Lagos and I love am—as I hope say you go see.”

Tunde's book is available now

Tunde Ososanya's winning book, LAGOS, LIFE AND SEXUAL DISTRACTION, is available online all round the world and from bookshops in the UK, USA and Canada. Bookshops in other countries should be able to order it through Gardners, Orca or the publisher, EnvelopeBooks.co.uk.