Foreword of the first edition of The Magic of Opals by WO Brown 1972

Only WO Brown can truly claim the title of the “Wizard of Opals”. He was the first opal miner to understand the deep connection between the Australian landscape and man, and this has influenced his writings on opals for the past 50 years.

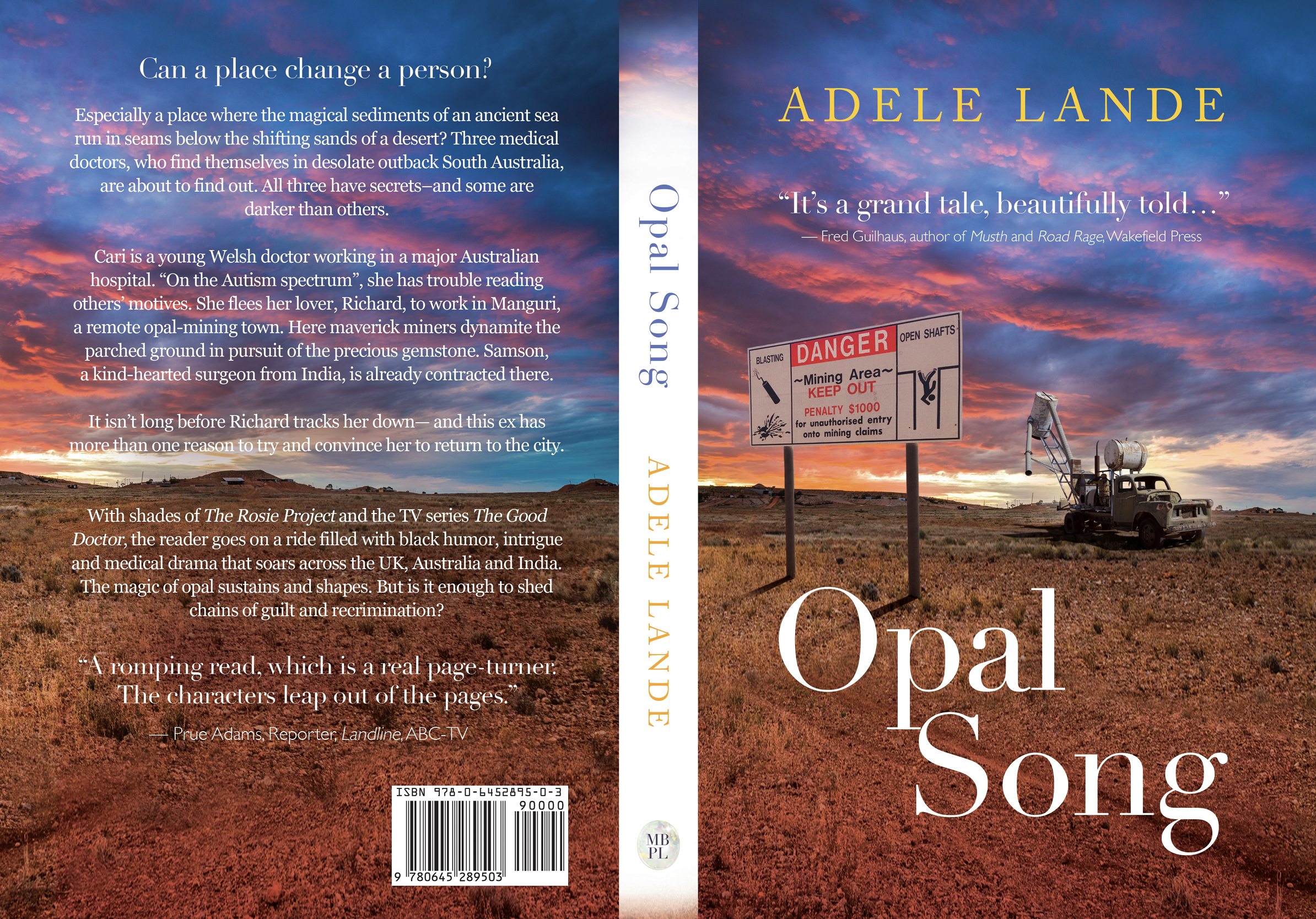

When WO Brown was a young man, he made his first trip to the Australian Outback, where he prospected for opal near the new township of Manguri, in South Australia’s far north. Although his prospecting yielded little over the years, knowledge of the local Aboriginal tribe’s history and traditions was his treasure to keep. Perhaps Manguri is where he began to appreciate the spirituality of the opal gemstone. After all, memories of ancient seas are locked within the stone’s fiery milieu. Each type of opal has particular qualities, reflecting the changing moods of those oceans.

WO Brown has long held that anyone can access the magic of opals, even the most sceptical. He often experienced ridicule for his claims that opals call troubled souls to their ancient sea beds. Although this precious gemstone can be more valuable than diamonds, I agree that many miners do not just dig for riches, but rather to heal a perturbed psyche. I should know, for the last 22 years I have prospected for opal in Manguri.

In the pages of this thoughtful, entertaining and inspiring book, the history and hitherto secrets of opals are shared by my good friend, WO Brown. Believe in magic or not, opals bring joy to anyone, wearer or not, alike.

Dimitriou Scoumbros, Manguri mayor and miner, 1972

1

Chapter One Cari 1/9/2015

Opals can be beneficial for anyone; they bring luck. Any of these colorful gems promote healing, whether it be from the pain of suppressed memories or from the torment of frustrated love and desire. It has been said that the wearer is released from inhibitions, allowing passion to enter their lives.

(The Magic of Opals by WO Brown 1972, p. 4)

If I could have read the faces of my colleagues and friends after they learned I’d bolted to Manguri all those years ago, what would I have seen? Curiosity, worry? Fear? Or perhaps, a quiet happiness and relief?

Finally! they’d think. She’s woken from her coma of blissful ignorance and is at last escaping that philanderer’s slick clutches. After all, the people I’d known then were wise about things I didn’t have a clue about. Not until that day, when the brutal truth about who Richard really was smacked me hard across my backside and then sent me scurrying north to a different fate.

Ironic isn’t it? A doctor and a trainee surgeon. You would think I’d have known better. I was always considered the bright girl when it came to facts and figures. Scholarships and prizes paved my way, sealed by a good work ethic. I like to think I had always been a good diagnostician, a good medico. I had never been great at the touchy-feely hold hands bravado. Anesthetized patients I understood, not the walking, talking variety. Sick people trusted me to do the right thing; I always delivered. But when it came to matters of love, the heart and romance and all that gooey stuff, I was and sadly still am—even now, 18 years after Richard—a total klutz.

You know what? Most people think surgeons are the superheroes of the medical world. We’ve all seen the pictures on TV—scalpel-wielding surgeons in army field hospitals, battling insurmountable odds, almost dropping with exhaustion, while bombs rumble outside and lights flicker. What’s not to admire about a doctor who can save a life or limb with the

2

simple knot of a ligature? It’s little wonder many a young doctor harbors a fantasy to join those elite ranks.

But that’s not why I started training as a surgeon. For me, it was because the body is knowable—it follows rules. And I did like that idea—that I could remove diseased flesh and destroy terrorist malignancies with deft cutting, attention to detail and fancy needlework. But that doesn’t mean my skill to prune malevolent growths extends into my personal life. I wasn’t so great at severing the manacles chaining me to my pathological relationship with Richard. Like an aggressive cancer, he came back. Some surgeon, hey?

I had no idea that day, when I sprung him in that nondescript storeroom, that Richard’s actions would catalyze a chain reaction resulting in my flight to the deserts of the Australian Outback. Or that some years later, I’d visit two hospitals in southern India and repair my damaged friendship with Samson, my Manguri colleague and mentor.

I often reflect with the passage of years, how my life could have taken a different path, were it not for one simple mistake on my Manguri contract—only discovered upon my arrival. If that hadn’t happened, Richard and I would have had very different fates. We would have quietly slipped away from each other. But the mistaken substitution of one town name for another by the agent who organized my placement, on an otherwise exemplary document, changed everything. And Richard, Samson and I therefore ended up in that remote mining town: it was an intersection that would change all our lives forever.

My recollections have become blurred through the dulled lens of time. Faces and names no longer take form in sharp focus. But I still remember that journey to Manguri as if it was yesterday. I was 25 years old, a Brit with no experience in bush medicine. The fact that I took that drive shows how desperate I was. It also shows how little I’d thought about what could happen; how inexperienced I was in most aspects of life. But I will never regret my years in Manguri and, even today, it is a rare day when my memories are not tugged back there by a random sound, a smell, or even a smile, taking me back to the people I knew then.

3

Chapter Two

8/9/1996

The Fire Opal is a playful opal; it is said to incorporate the energy of fire. It stimulates libido and action; lovers needing an energy boost are counseled to wear this fiery gem. But the benefits of the fire opal don’t stop there. It can attract customers to a business and can stimulate initiative. (The Magic of Opals by WO Brown 1972, p.150)

It was mid-afternoon, on that first day all those years ago, when I turned off the main bitumen highway onto the potholed narrow road leading into the small town of Manguri. Puzzling brown and white jagged earth mounds bordered the road. There was no green foliage to be seen, only red sand and gray gravelly earth. And, other than the odd rusting car wreckage every few miles, there was no sign of human existence. When my friend Linda said Manguri was “out the back of beyond”, I didn’t question her. Yet this reality was more desolate than I could have imagined.

I had purchased my red secondhand Ford Escort in Adelaide only a few days before. A car mechanic had checked that it would make the distance: a journey of about nine hours from Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia, which I would need to complete over two days.

Gusts of strong wind buffeted my small car as I drove north. I was glad to escape onto a secondary road, away from the road trains that thundered past me with a scary regularity. Some were three trailers long, causing my little car to become momentarily airborne, as if trapped in one of the red whirly whirlies that I could see agitating on the horizon.

I’d set off the day before in the early afternoon. To my surprise, I found the journey itself to be mesmerizing. The landscape was full of dramatic contrast. An hour after I left Adelaide behind, I was passing rippling fields of green wheat, rich with a promised harvest of grain. Ghostly white wheat silos appeared to float above the plains in the distance, overshadowing small farming communities. Later, the mountains of the Flinders Ranges, glowing red and purple as the sun set, formed a spectacular backdrop to the town of Port Augusta. I turned off there to spend the night. I stayed in a boxy but clean motel unit, before setting out the next day to make the six-hour drive to Manguri.

4

As I drove I often noticed my pulse was beating fast and my mouth was dry. An effect of adrenalin surging through my bloodstream, no doubt. Was it brave or foolhardy to go bush with my limited experience? Best not to think about it, I decided. This didn’t change anything and was pointless rumination.

Soon I was passing expansive salt lakes, shimmering in the glaring sunlight. These gave way to vistas of gray scrublands with black-stemmed scraggy trees. As I headed further north, the terrain became more barren and hilly and the soil now turned shades of red mixed with ochre. A pack of haughty emus strutted across the road at one point, causing me to brake suddenly. Some of them stopped and glared at my car; I was a trespasser on their territory.

After driving for five hours, I stopped to rest and to gaze from a lookout over the undulating floor of a long-dried antediluvian sea. I struggled to identify the feelings that were aroused by the magnificence before me. This landscape was so different to the rolling green hills of the Wales of my childhood. There, there were markers of civilization wherever you looked. Then I got it: what I felt was inconsequential—I was dwarfed into insignificance. This ancient landscape almost frightened me with its beauty, its destructive power. Seemingly empty, yet full of hidden life.

I needed to keep moving. A breakdown in these parts could be catastrophic. The swooshing growl of the road trains gave cold comfort. The dust clouds mushrooming in their wake seeped into my car through the air vents and furred the interior; I could even feel dust forming a fine grit between my teeth. The tinny music of a local radio station blared from my car radio. I sang to stay awake and to stave off niggling worries. On this second day signs of human habitation became very rare. I passed only a few small settlements, with the odd roadhouse and caravan park.

After several hours, I turned off the main road and headed into the township of Manguri. As I drove this final leg, I recognized the emotion that swelled within me. It was raw pride—I had done it. Even though logically there was nothing to suggest I wouldn’t or couldn’t, I still allowed myself to experience that warm sensation. I’d left Richard and our life together behind. And, more to the point, I had made it.

5

Chapter Three

I have often reflected how the sunsets of the Australian opal fields are mirrored in the colors of the gemstone. Every opal has all the colors of a rainbow, if you look closely.

(The Magic of Opals, by WO Brown, 1972, p. 1)

I spent the first night of my Manguri adventure at an underground hotel, just off the main street. Cafés, shops selling souvenirs and clothes, a supermarket and a few restaurants lined each side of the thoroughfare. The town seemed so foreign—I couldn’t relate it to anything I’d seen before. Dusty, was my first impression. Four-wheel-drive vehicles parked in the road were blanketed by the fine red powder which coated everything. Fronts of houses and hotels seemed to rise up out of walls of red earth with their bodies submerged underground. The streets were strangely empty. I later found that, shockingly, most of the townspeople and tourists were spending the daylight hours partying in underground hotels.

It was late afternoon by the time I arrived, and I headed to the hotel I’d booked through the local tourist bureau. The hotel foyer looked more like a jewelry store than a hotel’s reception. Glass cabinets housed opals of all shapes, sizes and value, including one fiery red opal. It reminded me of a crimson light flashing outside a house of ill repute. I felt my cheeks grow warm. On a whim, and unusually for me, I purchased it, a small ring with a gold band.

Exhausted, I ate dinner in a hill-top restaurant overlooking the town and offering a panoramic view. The sun setting behind the hotel transmogrified the valley below from red and brown to a super-saturated orange-red, the same color as the stone in my ring. The sky turned cerulean and purple, before stars gradually began to sparkle over the eastern horizon.

Walking back towards my hotel along the main street, I heard the screams of a distant fight that sounded like it was between two women. I quickened my pace to enter by the hotel’s side door, then descended a flight of stairs. Soon I was back in the soothing protection of my underground room. I suspected that living underground, as I had read people did in Manguri, would suit me. The inside temperature was always the same: 23 to 25 degrees Celsius (or 73 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit), hail, rain or shine.

The next morning, I arrived at the hospital earlier than needed. I took a taxi (also thick with dust) driven by a man with a Yugoslavian accent. Perched on top of a steep red hill, the hospital building was visible from all over town. The exterior looked run-down. The white

6

paint on the balustrades and posts was peeling and faded, the cement footpaths badly cracked. Clearly, someone wasn’t doing their job. Maybe, I thought, I should bring this to the attention of the hospital’s director.

The letter from the recruitment agency asked me to meet with the Director of Nursing at the main reception desk. I carried a copy of the contract in my handbag.

“Good morning,” I said to the young woman seated behind the front reception desk. I gave her a toothy smile, this always assisted with enquiries. “I have an appointment to meet with the Director of Nursing at nine o’clock. My name is Dr Cari Rainsford.”

The receptionist blinked a few times. “I’m sorry, she’s not here. She just left to go down to the Aboriginal Health Clinic. Is there someone else who can help you?”

“No,” I said, using my Pleasant Voice. “I have an appointment with the Director of Nursing.”

“Oh.” She looked me up and down. “Hang on a tick. I’ll just find somebody else who can speak with you.”

She disappeared for a few minutes, then returned with a largish woman wearing a nurse’s uniform of white shirt and blue slacks.

“I’m Jo Robertson,” she said, offering me a hand, which I reluctantly shook. The latest research suggested that bacteria and viruses were readily transmitted by hand shaking and should be banned in hospitals. But, in this remote place, she may not have read the journals yet. “I’m the clinical nurse on today. How can I help you?”

“I’m Dr Cari Rainsford. I’m the new doctor assigned to work here. I have an appointment with the Director of Nursing at nine o’clock.”

I pulled the contract with the covering letter out of my bag and tapped it loudly with my finger.

Jo hesitated, before asking, “Are you sure it was Manguri, you were supposed to be? We’ve just had a new doctor sent to us. He started two weeks ago.”

7

I felt a surge of irritation. Of course it was Manguri! The hospital’s address was printed in black and white, along with the starting date of my appointment. There was nothing to argue. I thought about Dr Smythe, my psychiatrist in Bristol many years ago. Her words still echoed in my head. Now Cari, I want you to smile. Best not to start off on a wrong note. I therefore smiled and again I showed my teeth fully, before saying, “Yes, I’m quite sure. I organized this placement through the recruitment agency only two weeks ago. Look—it’s all here.”

I passed over the small bundle of papers and Jo scanned it, her eyes widening. She looked up and passed the document back to me. She turned and called out to the receptionist I’d spoken with. “Ange! You’d better ring clinic. Tell Dee to get back here right away.” Under her breath, she said to no-one in particular, “She won’t believe it. Two doctors in Manguri at the same time. That’s going to be a first.”

Jo seated me in the staffroom to wait for “Dee the DON”. A pin-up board fixed above the sink was decorated with photos of people at parties, looking extremely silly and grinning. I stared at the images: most of the partygoers appeared to be in fancy dress, holding bottles of beer and toasting the camera. No wonder the building was crumbling if this was the culture of the workplace. I made a mental note to also discuss this sad state of affairs with the hospital’s director. Perhaps it was just as well I had been assigned to Manguri.

Soon a small woman came rushing in, followed by a short brown-skinned man of slight build.

“Hello, I’m Dee Edwards, the Director of Nursing,” she said, after taking a few calming breaths. I stood and introduced myself.

“And this is Dr Samson Cherian,” Dee continued, “who is... who has also been sent to us by the recruitment agency.”

Dr Cherian extended a fine-boned hand which I shook somewhat gingerly. Surely as a doctor he knew the risk of passing contagion on by shaking hands? He smelled of coconuts and strongly of something else, which I later recognized as Brut 33 aftershave.

“How do you do?” he said.

Dee sat down next to a table and spoke before I had a chance to instruct my new colleague about the importance of hand washing. “We have a problem, however,” she said. She tapped

8

her fingers on the table and appeared to be thinking. “We were only supposed to be sent one doctor, not two.” She glanced at Samson. “Truth be told, I was only expecting Samson to fill our vacancy.”

Smile Cari! Dr Smythe instructed from the deepest reaches of my brain.

I summoned up a grin. “I’m sorry? I don’t understand. I have a contract to work here for three months.”

In fact, I didn’t feel sorry at all. I was just putting Dr Smythe’s lessons in how to conduct appropriate social intercourse, from all those years ago, into practice. I had a contract. And that was it as far as I was concerned. Find another placement for the other doctor.

Dr Cherian sat down. He twirled a gold ring on the mid-finger of his right hand. “I also have a contract, Dr Rainsford,” he said quietly. “And I have come all the way from India especially to work here, for two years.”

“And I came from Wales,” I retorted, “which is further away.”

Keep calm, Cari ... Dr Smythe whispered, and smile!

The Indian doctor and I eyed each other warily. I was still standing. My hand hovered over the contract in my handbag at my side, as if about to grab a loaded gun from its holster. His head gave a slight wobble as if he had an unstable neck fracture. He looked nervous. Even I could see that from his tensed, rigid stance. His thick black hair was slicked down and parted on the side above chunky black-rimmed glasses that could easily have doubled as miniature picture frames. He wore a short-sleeved shirt with a gray leather tie. How ridiculous, I thought, eyeing that useless ribbon of fabric dangling from his neck. That could carry multiple strains of bacteria or viruses and infect half the hospital! Several ballpoint pens bulged from his shirt’s top pocket, which was tucked into high-waisted mud-brown polyester trousers. He looked like he’d wandered off the set of a 1970s police TV drama.

“Now, doctors,” Dee said, softly. “I’m sure this can be worked out. There must be some kind of mistake. I’ll ring the agency straightaway.” She departed, leaving Dr Samson Cherian and I to stare in silence at the pin-up board with its stupid laughing faces. I decided this was not a good time to remind him that sloppy handwashing techniques and the wearing of ties could be the genesis of a pandemic. That advice could wait for later.

9

A few minutes later Dee returned. She was rubbing her (hopefully sanitized) hands together. “Well, there’s been a monumental cock-up,” she said. “The agency put the wrong town’s name on the contract. Cari, you were actually supposed to go to Maitland. But, as it turns out, they also recruited another doctor for that post by mistake. He’s already working there. So, Cari, it looks as if we may get to keep you—that’s if the health department will allow it. And, presuming you wish to stay of course.”

I nodded. This was indeed a plausible explanation, exonerating her from fault. Dee disappeared again, to make more phone calls. Dr Cherian announced he had work to do and indicated in a friendly manner that I was welcome to join him. At a loss to know what else to do, I found myself following him. He collected Jo and the three of us started a ward round.

Watching Dr Cherian’s interactions with the patients, I noticed his tense manner soon change to one of unruffled purpose. He went about his work with a minimum of fuss. In contrast, when I thought about it, my extraverted ex, Richard, also a doctor, had acted like a one-man oompah band. Covert trumpets blared and cymbals crashed on his ward rounds, nurses and patients equally entranced by the rollicking fun and festivity of his manner.

It dawned on me after a while that my new colleague felt pleased— and maybe even relieved—to have my company. Although Dr Cherian’s clinical skills were excellent, I was more up to date on certain treatments. I spent some time explaining to him the recent recommendations regarding smoking-related lung damage, for which he murmured his thanks several times. Given this obvious show of appreciation, I then regaled him with the new evidence regarding rare occupational lung diseases, just announced in The Lancet. However, Jo cleared her throat just as I reached the climax of this explanation and informed me that ward duties did not allow time for doctors to pass time in idle chitchat. I was shocked at her flippant remark. The ward was clearly not busy. I pointed this out to her, using my Pleasant Voice. Samson quickly agreed with me that this was indeed important information and that when we were finished, he would be delighted to learn more. Maybe, I hoped, this response was a sign that we would make a good team. After arranging for the discharge of several patients and assisting Samson with writing drug charts, it was nearly lunchtime. He insisted I should call him by his first name, impressing that he was not one to stand on formality. I noticed that the nurses, however, all called him Dr Cherian.

10