In early fall 1864, the air was cool in Cross Keys, yet the foliage seemed green. Glimpses of Muscadine and Scuppernong vines loaded with ripened grapes appeared along the dusty dirt road. Great clusters of persimmon trees hung over the road, with bright orange fruit ready to drop from the branches. There in the low and wooded fields, like any scenic Mid-Atlantic countryside, was the Cross Keys, a scarcely populated neighborhood in Southampton County, Virginia. The neighborhood is at the north-east junction of Meherrin Road and Cross Keys Road north of Boykins Depot in Southampton County. It lies near the North Carolina state line seventy miles from Norfolk, and just as far from Richmond. Cross Keys is about fifteen miles from Murfreesboro in North Carolina, and about twenty-five from the Great Dismal Swamp. At a secure distance off the road, obscured amid the woods, stood an old decaying grand house. Aligned behind it is a neat Con-federate encampment of white tents, drilling for deployment in near Petersburg, Virginia.

Slaveholders in Cross Keys and across Southampton County expected that a slave uprising would go with the start of the war and tightened plantation discipline earlier, during the spring and summer of 1861. As an in-creasing number of white men left home for the Confederate army, however, and the dreaded slave rebellion never materialized, white Virginians loosened their grip on their slaves. In the county, slave patrols dwindled in number. In the absence of male authority figures, plantation discipline relaxed as slaves sensed and exploited their mistresses’ weakness. While a few slaves stopped working entirely, others refused to grow cash crops without extra incentives.

In its earliest stages of the Civil War, the practice of living off the land was a way of supplementing the army rations shortage. Food was the first area in which soldiers engaged in large-scale theft from civilians. Initially, soldiers in both armies freely picked apples, pears, and other fruit from trees they passed while on patrol in the county. Many soldiers in the encampment came from farms themselves and knew the labor and investment that went into raising field crops and filling storage facilities. The thought of foraging the productions bothered them. But as the war dragged out, the attitudes of Confederate soldiers toward supplementing their diet with the practice of living off the land changed markedly. Once a few members of the encampment crossed an inhumane line by taking food from civilians for their own consumption, the behavior inevitably spread to other soldiers. The Cross Keys’ residents competed with the encamped Confederate soldiers for the food and rummage.

In the spring of 1861, the bitter north and south sectional conflict that had been intensifying over four decades erupted into a Civil War, when states began seceding and formed the Confederate States of America. At its outset, the Civil War was not a war to end slavery, rather, to save the Union. In the states that seceded from the Union, three million Black people were in bondage, existing without human rights solely to serve the political, economic, and social benefits of the slaveholders. As the war progressed and conditions worsened, Southampton citizens faced greater and greater hardships and devastation. The enslaved people in the county endured much harsher conditions under strict slave codes and oppressive racism in the Cross Keys.

During the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln’s antislavery views were well established. His victory as the nation’s first Republican president was the catalyst that pushed the first southern states to secede. Lincoln sought foremost to preserve the Union, and he knew few people would have supported a war against slavery in 1861. Young Parson Sykes, however, hoped that the war’s outcome would rid the status quo by abolishing chattel slavery.

For over 150 years, Parson Sykes’ descendants passed down stories and adventures of his early life at family reunions and holiday meals, weddings, and other gatherings where the ancestors met. As told by his son, John P. Sykes, Parson was born and raised on Jacob Williams’ farm in the Cross Keys neighborhood about fifteen years after Nat Turner raided it during the insurrection. He was the son of Solomon Sykes and Louisa Williams. Louisa and her three sons, Parson, Joseph, and Henry were slaves on Jacob Williams’ farm. However, not much was known about Solomon, who may have been a slave on a nearby farm and hired out to Jacob.

Solomon Sykes was a skillful farmer who Jacob Williams hired to supervise his tobacco, peanuts, and cotton interests on his three farms. Louisa did all the cooking, cleaning, washing of clothes, sweeping, food service, and childcare. She also had to be alert at any hour of the day or night. She lived in a small two-story slave shanty with an open second floor, where Parson and his brothers slept.

According to oral family history, early in his life, Parson worked on the farms. He followed along beside Solomon and the other older workers, and as he grew older, became an experienced substitute for Jacob Williams’ aging slaves. During the war, he learned to tend the horses, drove the carriages, and kept the gardens. On Jacob farms, enslaved children, from the age of about ten, suffered exposure to the ills of slavery, working full-time work, with the threat of family separation, and denial of basic human and civil rights.

For his own predatory benefits and needs, Jacob trained Parson, Joseph, and Henry to be carpenters and farm laborers. He was one of many farmers in the county who violated the law and instructed the enslaved people on his farm to read. In addition, Jacob ensured they learned and obeyed his rules and laws that denied slaves human and civil rights. Parson understood as a slave, he could own nothing, not even his labor that served the political, economic, and the social benefits of Jacob, his enslaver. Parson was good with artisan tools. He was not afraid of heights or climbing on the roofs of tall barns and farm buildings. On and off the Williams Farm, there was always a need for enslaved journeymen who could do a wide variety of farming, blacksmith, and carpentry duties.

Jacob supplied the family with a poor diet. Louisa supplemented it by subsistence farming a small plot of land and her sons’ small game hunting. He did not supply ample clothing, and Louisa worked at night after long days of labor to clothe the family. For Parson, Joseph, and Henry, the war bought an even heavier workload. Sometimes, Jacob allotted them the bare minimum of food and clothing; anything beyond that was up to the family to gain.

Parson and other children in the county shared an excitement about the war and an interest in the political and military affairs going on during the war. They enjoyed watching soldiers’ drills and ran along beside military units as they paraded through the streets and fields. Watching the steamboats sail along the Blackwater River during the Civil War was an unforgettable event for the children. Both Union and Confederate forces in Virginia used steamboats to move troops and cargo to their operational supply centers and strategic hubs.

As the war progressed and conditions worsened, as the Confederacy faced greater and greater hardships and devastation. Parson hoped the war’s outcome would overthrow the status quo by outlawing the centuries-old chattel slavery institution.

In 1864, Parson was reaching draft age, and Jacob Williams needed his labor on his family farm in the peanuts, cotton, or tobacco fields. When he was not working in the fields, he built and maintained structures on the plantation house and complex, or Jacob hired him out to the railroad company to do basic carpentry, light building maintenance, and janitorial work. Because Parson was reaching draft age, Louisa feared the Confederacy would impress him into the army if he did not liberate himself. She was happy to see that all her sons were interested in the Union Army.

According to a family anecdote, Jacob hired out Parson to the Seaboard & Roanoke railroad company to re-place white male shopmen pressed for military service. Parson performed janitorial and light carpentry tasks in the depot. Its waiting room had restrooms for male and female patrons. The south side of the building had a baggage and mail handling area. These areas often held forbidden documents and mail confiscated from passengers by confederate patrollers. Above the baggage handling area was the telegraph office, the confederate mail room, and an area used for record storage. Parson cleaned these areas and emptied trash bins of discarded newspapers and records. He refrained from reading in front of others in the depot. He earned a dollar and a half per week when hired out by Jacob Williams, who took half of the pay. The depot also served as the assembly hall for the Home Guard in the area and used for moving Confederate troops and supplies.

Parson secretly collected discarded newspapers, magazines, and other documents to perform research on ways to strike out for freedom. Each day when his work at the depot ended, Parson spent time in a secret haven, alleged to be the old forgotten home owned by Nathaniel Francis, another casualty of the insurrection. There, near a barely recognized pig-path, hidden beneath the vines and fallen trees, to avoid Jacob’s suspicion, he had about one hour in which he researched and read the discarded documents he hid there. Continuous research and acts of resistance fulfilled Parson’s daily life on the Williams’ farm. Although the laws denied him freedom, Parson used a wide variety of tricks to contest Jacob’s power, and to assert his human rights to control his own life. Jacob Williams depended on involuntary labor to keep his farm solvent. Parson and other en-slaved workers often used work slowdowns to resist theft of their labor.

When the sowing season started, Parson spent time with his two brothers and close friend, Henry Charity, discussing human rights and political implications of the abolition of slavery. About the same age as Parson, Henry Charity, was a freed Black man who worked on different farms in the county. He told Parson and his brothers how memories of the Nat Turner haunted Jacob Williams. Like other enslavers, he expected that a slave uprising would come with the start of the war and tightened plantation discipline.

Parson often described to Henry Charity how Southampton slave codes made it illegal to teach slaves to read. The codes restricted the marriage rights of enslaved people, to prevent them from trying to change their masters by marrying into a family on another farm. They restricted marriage between people of different races. The Virginia slave codes prohibited large groups of enslaved people from gathering away from their farms. He told Henry Charity that the slave codes on slaves’ punishment had no penalty for accidentally killing a slave while punishing them.

Parson had no way to protest to Jacob’s harsh treatment and abuse legally. In Virginia, most slave codes concerned the rights and duties of slaveholders and not about aiding enslaved people. The codes left a great deal unsaid, with much of the actual practice of slavery being a matter of traditions rather than formal law. There were similarities between the state and county slave codes. Henry Charity, mesmerized by Parson’s urgency to escape from slavery, reacted by promising to support his courageous quest for liberation from bondage with any means and ways he could.

In 1864, Jacob managed the three family farm operations, which included tobacco, peanut, and cotton crops. Jacob organized and guided daily farm activities, including slave control, management, training, hiring out, and mating. Caswell Worrell, his nephew, and the overseer helped him by supervising slave labor and other related tasks as directed by Jacob.

As described in David F. Allmendinger, Jr, version of the Southampton Insurrection, the Williams farm in Cross Keys, belongs to three members of the Williams family: to Jacob Williams, to his nephew William Williams, Jr., and to Jacob’s sister, Rhoda Worrell. The first of their farms heading toward the Cross Keys, on the north side of the road, belonged to William Jr., son of Jacob’s brother Kinchen. A quarter of a mile farther east and across the road to the south stood Jacob’s house; and a short walk from there, but still on Jacob’s property, near the road, stood his overseer’s cabin, occupied by another nephew, Caswell Worrell, the son of Jacob’s sister Rhoda Worrell. Caswell’s mother had lived on the plot of seventeen acres a short distance east of the cabin, but well south of the road.

Henry Charity knew Jacob Williams was a long-time enslaver in the Cross Keys neighborhood who hired him and other freed people. In 1864, at eighty-four years old, Jacob showed no inclination to change his ways and views. He was quick to judge others based on their appearance, their clothing, speech, and other human traits. He mistreated Black people because he considered them inferior to white people. Henry Charity saw his racist, white supremacy values and politics that characterized him before and after the Civil War. To Jacob, keeping the status quo was the same as supporting law and order. He saw Black people as more violent and dangerous, not disturbed by harsh labor, physical brutality, and not fully human. He received help from institutional racism and promoted racist ideas that boosted him in status above Black people.

Jacob held upholding white supremacy as a justifiable cause for the state to secede and join the Confederacy at the outbreak of the Civil War. He worried that Parson and his brothers might rebel and self- liberate. As a survivor of the Nat Turner’s Rebellion, Jacob knew this better than other Southampton slave holders. Jacob used the Bible to justify the economical use of slave labor. He took his subjugation of Parson and other slaves as his natural right. Parson’s subordinate position to his relationship with Jacob ex-tended to his relationships with all Southampton white citizens. Jacob mistreated slaves and used fear and violence to control the Black people. As a result, slavery not only broke people’s bodies, but it also crushed their spirits. Parson and his brothers worked from dawn to dusk from Monday through Saturday. Sundays were a day to rest and worship. Jacob’s farm operations included livestock management, crop cultivation, and other agricultural enterprises. He grew tobacco on his farm, peanuts on his sister’s farm, and cotton on his nephew’s land.

Jacob’s wife, Rachel, headed the domestic labor and supervised Louisa, who did the cooking, cleaning, washing of clothes, food service, and childcare. Louisa, about four and a half feet tall and one hundred pounds in weight, lacked visible interest in political, social, or personal relationships, preferring to be alone. She gave an appearance of being cold or indifferent to others and had little or no interest in men other than Solomon.

Parson disagreed with the ways Jacob subjugated him and sought ways to resist the denial of his basic human rights. Observing the relationship between Jacob and other whites, he conceived the moral principles or norms of human behavior that laws protected as legal rights. To Parson, everyone born on earth inherits human rights that embraced no less than freedom of opinion, expression, thought, and religion. They also included rights to life, rights to education, rights to organize and rights to fair treatment. Absolutely, no one in Southampton should be a slave.

Parson and his brothers hated and feared Jacob Williams. They felt he stole labor from them to cultivate the farm and enhance his wealth. To profitably cultivate the land, he needed unpaid slave labor and reasonable liberties, without government interference, to do as he pleased. Parson routinely looked for and found countless acts of resistance to Jacob’s domination in the daily farm operations. At its peak, the farm holdings altogether amounted to just twelve slaves, half of whom never belonged to Jacob. He habitually reminded the slaves that they had no value as human beings. He, his family, and the overseer humiliated the slaves as a typical way of life.

Parson believed no one should exist in slavery or servitude, and the Union must abolish enslavement in all its forms and in all places. Fleeing enslavement and running to freedom was a dangerous and potentially life-threatening decision and, if caught by a fugitive slave patrol, it would return him to Jacob Williams, who would then brutally punish him. Because of his fascination with freedom, Parson secretly desired to liberate himself and enlist in the Union Army.

While walking down Meherrin Road after working in Boykins at the railroad company, Parson and his friend Henry Charity found time to discuss the course of the Civil War. They discussed emancipation, the Union Army invasion in nearby Petersburg, defeats of the Confederate armies, and the ongoing Union occupation of Suffolk. In 1864, three million Black people were still in bondage in the states that seceded from the Union existing without rights and under harsh slave laws and oppressive norms.

Parson and Henry Charity also discussed the two Confiscation Acts. Information reached Cross Keys that General Butler declared fugitive slaves contraband of war and employed them as laborers. Congress ratified Butler’s decision by passing the First Confiscation Act, and the Department of War and the Department of the Navy both allowed the employment of confiscated slaves as wage laborers. This was a major first step toward authorizing the Union Army to accept Black volunteers for military service during the Civil War.

Next, they discussed how freeing slaves would deprive the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor force and put public opinion on the Union side. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln realized he could not avoid the slavery question much longer. On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act, both of which allowed the president to employ Black Americans as workers or soldiers.

Henry Charity informed Parson about the Emancipation Proclamation. On January 1, 1863, United States President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in states that had seceded and are part of the Confederacy. It said that all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, where the people were in rebellion against the United States, are now and forever free.

Parson was glad to learn the proclamation also said that the United States military and naval authority, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and included the provision for enlisting former slaves into the armed services of the United States, to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places and to man vessels of all sorts.

Growing up in Southampton County, Virginia in the mid- eighteen hundreds, Parson was afraid to let anyone see him reading. To keep this secret, he collected discarded newspapers from the depot waste container. He learned a great deal about their military and civilian background retold the stories at family gatherings.

Union Army Major General Benjamin F. Butler, according to Parson, shrewd military leader and lawyer, was one of the most controversial men of the American Civil War. Abraham Lincoln appointed him for political reasons and Butler was the highest ranking general of volunteers during the war. Using a combination of power, craftiness, and energy, General Butler was a stern but patriotic leader who championed the rights of workers and Black people. In most assignments, he was the right man in the right place at the right time for the job.

After promotion to Major General of Volunteers, the Army transferred and assigned General Butler to command of Fort Monroe, Virginia. Soon, the news reached enslaved people in Southampton County that Butler declined to return to their owner’s fugitive slaves who had come within Union lines. He decided that the United States Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Act did not affect another country, which Virginia claimed to be. Enslaved men who found their way to Fort Monroe quickly became known as “contraband,” a term that marked their provisional state of being neither free nor enslaved. In later months, the Army adopted “contraband” into common use and signaled changing views of slavery in Ameri-ca. His decision, which came to be known as the “Contraband Decision,” enabled thousands of enslaved people from states in rebellion to seek refuge behind Union lines. However, no existing law or policy supported his clever reasoning, which supplied the Union with able-bodied men capable and willing to support the Union. In the following years, Butler’s decision had resounding military, political, and social implications as well.

The Union Army occupied New Orleans in the spring of 1862. A joint Union Army and Navy expedition accepted the surrender of New Orleans on April 26, 1862. But the capture of the city and the sealing of the mouth of the Mississippi was just the beginning of the Union Army of occupation. The Army transferred and assigned General Butler, commander of Union troops in occupied New Orleans for seven months, beginning in May 1862.

The Confederate government of Louisiana had formed a militia, including free Black men led by their own officers. This all-Black militia came to General Butler and volunteered to join the Union Army. He transformed the Confederate militia into the First Regiment Native Louisiana Guards, led by Black captains and lieutenants. The men in the regiment came from the New Orleans region. Most were free men of mixed-race whose families the Union government freed when New Orleans became an American possession through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. These men became members of the first, though unofficial, regiment of Black troops in the Union Army.

General Butler later formed two more Black regiments, commanded by white officers. To keep New Orleans in Union control and bolster troop numbers, on August 22, 1862, Butler issued a general order allowing the enrollment of Black troops. The Black people of New Orleans responded with enthusiasm. Within two weeks, he had enlisted over 1,000 men and formed his first regiment. The general order stipulated only the enrollment of free Black people into the regiment, but the recruiting officers were extremely lax in enforcing this rule, allowing many runaway slaves to enroll with no questions asked.

On September 27, 1862, the regiment officially became the first Black regiment in the Union Army. The 1st South Carolina held the distinction of being the first Black regiment the Union Army organized, but the Union Army had not officially mustered it into service. In August, the Department of War ordered Union General Rufus Saxton to organize a regiment of Black soldiers in the South Carolina Sea Islands experimentally. By the end of the year, Saxton had successfully raised the 1st South Carolina Colored Volunteers, and the regiment took part in raids on the Atlantic Coast.

Taking all of this into account, Major General Butler was a patriotic and skillful administrator who recognized and championed civil-military operations before the Union Army. He was the leader in granting human rights for Black people and their emancipation.

Comments

Add new comment

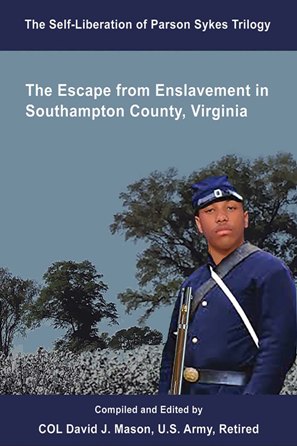

New cover added