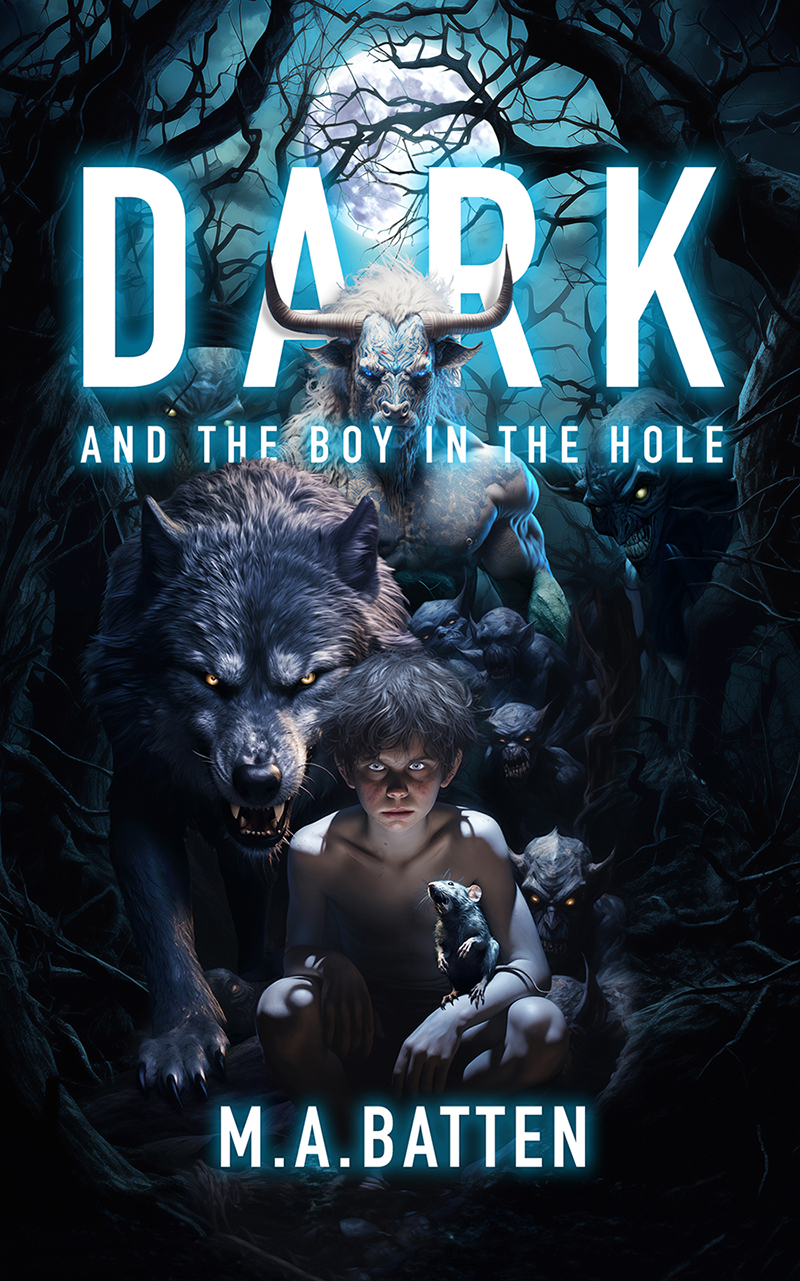

CHAPTER I:

THE BOY IN THE HOLE

The boy in the hole didn’t know his own name.

He probably didn’t even have a name. He had been in the hole for such a long time that he had only ever been called ‘It’ or ‘Thing’.

Or ‘Boy-in-the-Hole’.

He had no idea how long he had lived in the waterless well, held within its stone walls and kept from the world above. Everything he remembered of his life took place at the bottom of the cold pit. Every memory he ever had was confined within the darkness of the hole in the ground.

He did not even know how old he was.

Deep and dark, the cold walls of the hole bore the dank scent of a thousand years and sometimes the boy wondered if he had been there all that time. Since he knew of nothing else, it seemed possible that he was a thousand years old. Perhaps older, as though he had been in this exact place before there was even a hole and the earth had grown around him.

Even his dreams were of a life at the bottom of a hole.

Stale water seeped and dripped from the walls and made a small puddle to one side of the pit floor where a small iron grate no larger than his hand let the water flow away to some unknown destination, carrying with it the dirt and mess and filth left by a boy who spent his entire life in a hole with no toilet.

The boy’s muck escaped from the hole. But not the boy.

At the top of the pit – a long way up – was another, much larger, iron grate blocking the way out. As wide as the hole, it was a criss-cross of a hundred iron bars with gaps just wide enough to let in light from the world above. Or muffled sounds or scents. Sometimes food scraps.

And taunts. From the people who did not live in the hole.

Over his lifetime, the boy had learned to carefully claw and climb his way up the ancient stone walls, picking out the gaps in the stonework with his fingers and toes. Wending his way up the slippery surface, stone by stone, brick by brick, he could reach the top of the hole. His dirty fingers could poke through the gaps in the grill and his face press against the underside of the iron bars to feel the fresh air caressing his grubby cheek.

After the difficult climb up the walls, his muscles burned from the strain and struggle, but he bore the pain to let the air tickle his skin and a world of foreign scents fill his nostrils.

He had been in the darkness of the hole for so long that the light in the world above would hurt his eyes and nearly blind him. He could only sustain a squint for a short time before his head began to ache.

He didn’t understand why the world above constantly changed from light to dark and back again, over and over, but he chose those darker times to claw and clamber his way up the ancient stones. When there was no light in the world above to blind his eyes, he could see perfectly through the dark of the world beyond the hole and its impassable iron-grilled ceiling.

Beyond the iron bars, the boy could see his hole was in the middle of the floor of a vast building. During the times of light, the place above was noisy, filled with clatters and clangs, and the hustle and bustle of many people who spent a lot of time doing nothing but living noisy lives.

Noisy lives that were not in a hole in the ground.

The enormous room above his subterranean world was made with stones bigger and smoother than those lining his hole. Around the room, gigantic carved columns taller than his hole was deep, and twice as wide, reached up to support a great arched ceiling that stretched out in all directions.

The walls were decorated with countless hanging cloths in a multitude of bright colours, each one picturing a different creature the boy had never seen. In one, a great scaly beast belched a stream of fire into the air as a victorious knight thrust his sword into its belly. Another showed a proud king on horseback, followed by two soldiers carrying a long wooden pole from which hung the bloodied body of a half-wolf half-man. And yet another depicted a line of brave knights riding into battle against an army of small, deformed men with green skin.

Between each of the ornate hanging cloths was a tall, narrow window looking out to the sky. Beyond these walls the boy could see such deep blackness and a thousand scattered lights, so tiny and white and farther away than anything else he could see. Often, he longed to be as far away from this hole as those beautiful sparkling lights.

Sometimes a billowing veil of smoky air drifted across the sky, high above the world of his hole, and wiped the twinkling dots from his view.

Occasionally, he saw Her.

She was a beautiful silvery white orb with soft blue-grey swirls and a gentle glow that came from within. She drifted slowly across the sky, peering her face down upon him through one window then the next. She didn’t speak, but neither could the boy in the hole, so they shared silent thoughts, he in his filthy wretchedness and She in all her magnificent beauty.

His Mother.

Or so he thought She must be. For She was the only thing he knew that was not cruel. Never taunting. Or vicious.

She made him feel seen, and he loved her.

With a longing sigh, he hoped that one day She would break through the solid stone walls of the great building, tear the iron grill off the hole and gently lift him into the world above, to be with her.

One darkness, as the boy clung to the caged roof of his pit and breathed in the sweet air of the dark and silent hall, a small creature came scurrying across the floor of the room and stopped when it encountered the boy’s fingers poking into its path. Slightly larger than his open hand, its grey fur puffed out to make it appear bigger than it was. The creature’s pointed nose twitched, nostrils flaring, and its beady eyes remained focused on the boy.

While there were thousands of them living within the walls of the castle, none had ever before appeared in the Great Hall which was almost always in use and most often guarded by two ravenous dogs who would quickly make a meal of a rat.

Slowly, the boy stretched one finger and gently stroked the animal’s cheek. Its ear turned this way and that, constantly alert to all around.

After what seemed like an eternity, but was probably only a few minutes, the creature scurried on its way, across the boy’s hand and along a single bar of the grill with perfect balance.

Over time, he faced the creature more often, always when the hall was unlit and quiet.

And one day, it spoke.

It didn’t use the words of people, instead making short squeaks and timid clicks but the boy somehow knew what it said. He could make sense of its voice. Sometimes the chatter was about the creature’s incessant nervousness and fear of every tiny noise, every little movement, every shadow. But mostly it spoke about food it had eaten, wanted to eat, or was about to eat.

Eventually, the boy tried talking back with a series of squeaks that he assumed meant, ‘I’m hungry too.’ And the critter suddenly cocked its head sideways, twitched its nose, wiggled its little round ears, and then hurried off.

When it reappeared, a small morsel of bread poked from its cheek. The boy thanked it for its generosity with a squeak and a click, receiving a pleasant squeak in reply.

That’s OK, boy in the hole, he understood it to say.

For the first time in his life, the boy had made a friend.

The visits became more regular with deliveries of crumbs of dry cheese or a shred of stale meat, until both the boy and the rat decided it would be best if they just lived together. The boy was able to pull free a loose stone from the wall near the bottom of the pit to make a small alcove lined with moss comfortable enough and safe enough for a rodent to sleep blissfully.

Every night, the boy would make the climb to the top of the hole with the rat clinging on his shoulders or in his matted hair, and let it scurry through the grate in search of food. Sometimes the scavenger would return with nothing, having been chased from the kitchens by the dogs, but usually it would drag back tidbits to share with the boy. On a more adventurous outing it managed to find some string and a discarded scrap of fabric the boy was able to fashion into a crude pair of shorts.

Once, it even returned with a shiny silver ring, the most delightful treasure the boy had ever seen, but he dropped it while climbing down the wall and it disappeared into the tiny grate at the bottom with a clink and a rattle. His fingers couldn’t reach in to retrieve it and the rat refused to squeeze through into the filth and muck beneath for something that wasn’t edible.

Through their chats, the boy learned of things beyond the Great Hall, but it was mostly focused on what food could be found, where it could be found, and when it could be found. The boy pressed the rat for other information, such as what lay beyond the walls of the Great Hall, where did the people go when they were not in the Great Hall, were there other boys in other holes in the floor of the Great Hall, and things that seemed curious and important to the boy. But the rat did not understand what could be more curious or important than food.

After much chatter, peppered with the locations of various food sources, the boy managed to learn of several people who did not live in the hole, such as the cook, the kitchen hands, the maids, and the butcher. Through their activities and the increase in food supplies it became possible to predict when the Great Hall was about to be filled with many people.

The people who did not live in the hole would sometimes gather in great crowds of laughter and feasting to a melodious noise made by people holding, hitting, blowing and strumming all manner of strange objects. Climbing to the top of the hole to watch the festivities, the boy was always careful his fingers didn’t poke through the grill or someone would tread on them, sometimes intentionally trying to make him fall.

Usually, the people forgot he was in the hole beneath their feet, but sometimes they would remember and stomp on his grill, shouting taunts. For amusement, they took great delight in dropping food scraps to him, emptying their cups onto his head or sometimes worse.

At times they played a game in which they poked sticks or swords through the grill to try knock him from his perch on the wall, sending him plummeting back down the hole. They succeeded once and he had been unable to walk or stand for a long time without his swollen foot shooting a spike of pain up his leg.

After that, he was always careful to avoid being noticed in the hole. With practice, he became better at dodging the probing weapons whenever the people did notice him or suddenly remembered he was at their feet. He even learned to quickly leap from one wall of the pit to the other, or to loosen his grip on the stones and instantly fall down the hole a little way before latching onto the stone walls again just out of their reach.

Of all the people who lived above the hole, there was one whose taunts were harsher, his games more wicked, his cruelty crueller.

On one occasion, the Great Hall hosted yet another party attended by many people dressed in fine clothing and masks, eating sumptuous food from a table that ran the entire length of the room. The unknown aromas of roast boar, baked vegetables, stew, fresh bread, pudding, cakes and biscuits wafted deep into the pit, curled into his nostrils and made his stomach complain. The people sang and laughed and talked and generally didn’t notice the hungry boy beneath their feet.

At one end of the room, people whirled and moved to music while men in colourful clothing flipped each other into the air, balanced on each other’s heads and entertained the partygoers with tricks and merriment. The boy was so focused on the dancers and the jesters that he hadn’t noticed the man sneak up on him.

Before he could let go of the grill and drop down the hole to safety, a heavy boot stomped down on one hand and held it fast. At the same instant, the other hand was grabbed by the fat fingers of the wicked man. The boy snarled and growled like an animal, his body thrashing about below the bars as he tried to wrench his fingers free.

The rat, sitting securely on his shoulder, buried into the boy’s thick mess of hair and hid.

‘Look what I’ve caught,’ the man boomed to his guests, and they all stopped to gawk and laugh. The boy could smell wine and ale on the man’s foetid breath as he leaned close to grin and stare through the grill, his eyes mad, his teeth stained, his beard filled with crumbs of food that had not made it to his mouth.

The man called for the poker to be fetched from the hall’s enormous fireplace. He raised the red-hot poker to his lips and blew on the glowing orange tip to produce a curl of smoke. It sizzled from the drops of spittle that flew from his breath.

‘It’s time I had my pet branded,’ he sneered. ‘How else shall anyone know he is mine if he ever escapes from his cage?’

He poked the glowing tip of the iron bar through a hole in the grille and pushed it closer and closer to the boy.

‘I should warn you,’ he whispered, ‘this will hurt like hell.’

It struck the boy’s shoulder and, even though it was just a light touch and only for a second, it burned and sent the searing pain of a thousand daggers tearing through his flesh. His body thrashed so wildly his fingers tore free of his captor’s grasp, and as the boy fell to the bottom of the pit his tortured scream was drowned out by the wicked laughter from the crowd above.

This man owned the Great Hall and all its ornate finery.

He owned the hole and everything in it.

He owned the very earth that swallowed the boy.

He even owned his own name.

King.

Comments

The greatest challenge of…

The greatest challenge of any writer is to create a world that the reader can willingly become a part of. Where everything is as real and plausible as the rather grey and mundane world we live in. To make the unbelievable totally believable. Relatable. Not only does this writer achieve that but he does so from the perspective of a captive boy who knows nothing at all about the world beyond the hole he is confined in. To make that feel as though we are there is masterful. To me, the icing on this fantastic cake is the rat with whom he forms an unlikely bond and is the means by which he learns about the world above the steel grill that is his only distorted view of reality. Not one line of dialogue is necessary and yet this is as compelling as any fast-paced, bestselling thriller. Perhaps even more so.

The simplicity of the…

The simplicity of the writing style is intriguing. The world is brilliantly set for us to see from the perspective of fresh eyes. I just believe that instead of relying completely on narration, we should see the character in action, to engage more with the story.

A well-written, horrendously…

A well-written, horrendously sad story!

Beautifully written. I was…

Beautifully written. I was immediately hooked. Well paced with compelling characters and descriptions.

Delayed gratification

This has a slow start for me, so it didn't pull me in right away. However, it's worth the wait for the reader.

What an opening

What an opening this is. Well written and so compelling. I feel I'm there with the boy and I'm truly intrigued to see where this story goes. Such an original idea. Well done.

I understand his desire to destroy...

The boy in the hole has never been outside, so he can only describe day and night as darkness and light, a dragon as "a great scaly beast belched a stream of fire", and the moon as a floating orb in the sky. Yet he is able to describe victorious knights, proud kings, and even half-wolves with striking clarity. I’m nitpicking here, but I would have loved to see more descriptive detail in some of the scenes where the boy described things he saw in his environment with his limited knowledge of social hierarchy and view of the outside world, especially as this is the introduction to the reader of how limited his world has been.

Overall, the story is beautifully written. A compelling, heartbreaking tale of a boy turned unwilling hermit by a cruel world. The characters are captivating, the story is gut-wrenchingly vivid, and if I’d been in a similar situation, I’d understand the desire to destroy humanity too. Truly a memorable read.

Hauntingly original premise…

Hauntingly original premise with genuinely touching rat friendship. Sensory details excel—the moon as surrogate mother is particularly evocative. Dark fairytale atmosphere is established effectively. Prose over-explains relentlessly ('waterless well' then 'cold pit'). 'Boy-in-the-Hole' repeated obsessively. Pacing drags through repetitive climbing descriptions. Lacks narrative drive beyond establishing misery

Hauntingly original premise…

Hauntingly original premise with genuinely touching rat friendship. Sensory details excel—the moon as surrogate mother is particularly evocative. A dark fairytale atmosphere is established effectively. Lacks narrative drive beyond establishing misery

Powerfully Atmospheric

The opening creates a powerfully atmospheric and emotionally resonant world through the boy's confined perspective, and the friendship with the rat is genuinely touching and well-executed. However, the first 10 pages don't yet hint at the intriguing premise (mimicry powers, monsters, uprising), which means the story needs to accelerate toward revealing these core elements that make it unique.