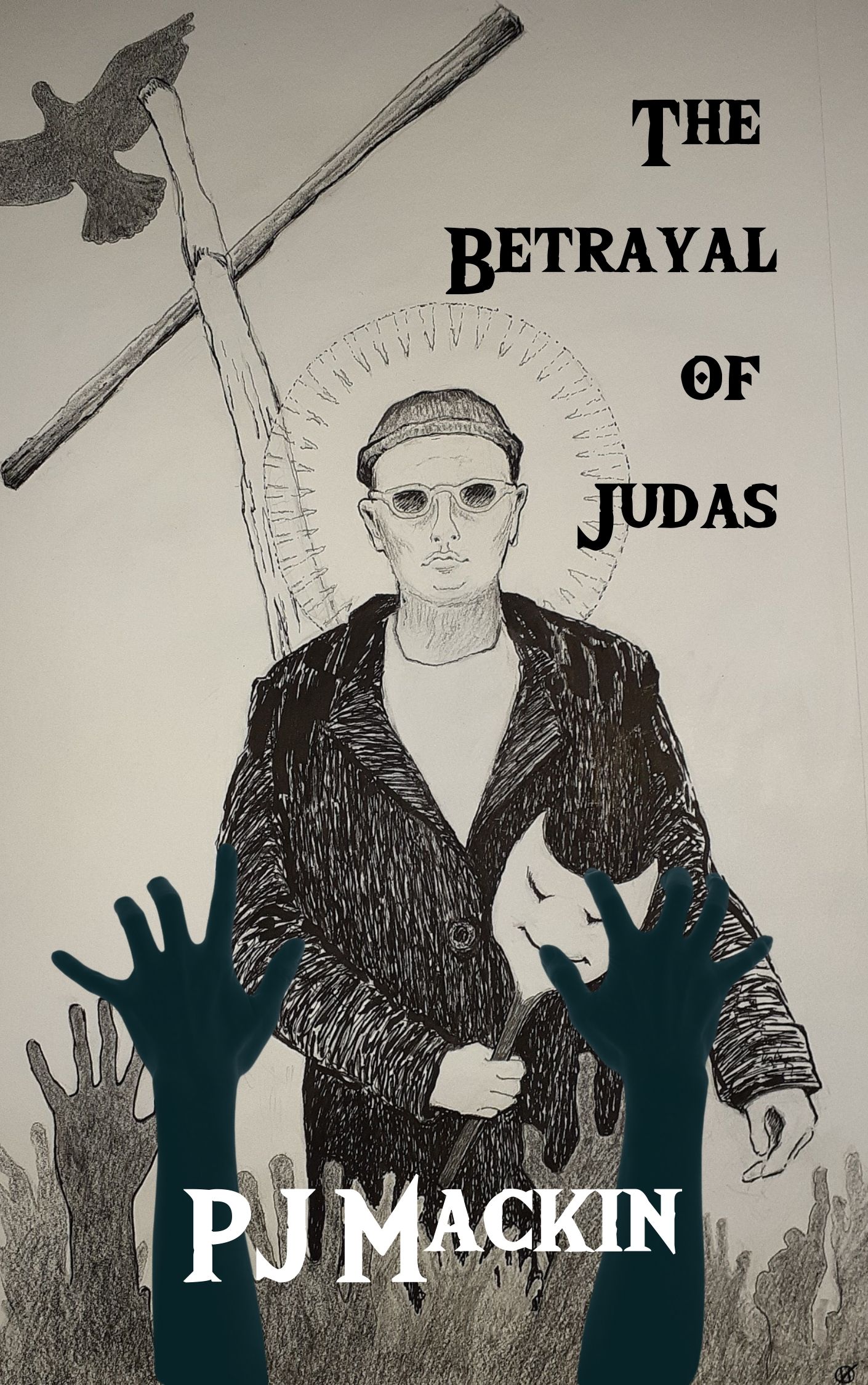

The Betrayal of Judas

Judas transforms before our eyes into a hardened survivor in a desperate struggle to find his brother and rescue the woman he loves. Innocent cunning triumph over the ancient orders of absolute faith.

The old homestead was built halfway up a mountain track overlooking the river. In the dry season, you needed a four-wheel drive to make it up and snow chains in winter when the ice settled into the muddy hollows. The weatherboards were chipped and old. The rusted out roofing iron rattled in the wind, which meant the racket never stopped.

Pop, pop.

The shooters always came after midnight. That gave the kangaroos a couple of hours to work their way down into the open fields where the shooters could pick them off at ease. Sometimes they worked in teams, traveling in pairs but tonight there was just one. Jud could tell by the sound of the rifle. Two shots fired through a silencer, each one followed by a rasping echo. The shooter sounded professional, patient. Two shots were all it took to make the kill.

Pop, pop.

Jud stared into space. The clock said 1:55 a.m. The alarm was set for 9 a.m., but he couldn’t sleep. Two days without a fix, three without a juice. That was the one single thought stalking him for the last twenty-four hours. He felt unnaturally awake, unable to remember the last time he’d been so far away from his dope rig.

The doctor said it would be the worst six days of his life. Junk sick was like having every strain of influenza known to man all at once. After decades of exhaustive research, the foremost medical consensus on how to survive heroin withdrawal was to clear your mind and stay focused. But how do you clear your mind when the double think of a junkie owns it?

All he knew were the cravings; he couldn’t focus on anything else.

When the cravings start, you acknowledge them. They are your limitations. Keep them on the boundary where you can see them from a safe distance. Focus on them, but never let them get close. What Jud needed was a one-stop pill to put him to sleep for six days, so he could wake up when it was all over. “I’m sure you’d love that,” the doctor had said.

He thought about the cupboard under the kitchen sink and the one emergency, roach-tipped, opium soaked, 16mg stick of glorious skunk weed magic that resided therein. It wasn’t much of a substitute for good morphine junk, but that was the closest thing he’d get to a six-day pill right there, the only solution to all his problems.

STOP.

1:57 a.m. and already, his resolve was bending out of shape. He had to think positively. The limitations were closing in. He could feel them burning up his arms, trickling through his skin, gnawing at his bones.

Pop, pop.

The gunfire made it worse. It made him jittery and breathless. He could feel the thin lining of his lungs catching with every breath. An asthma attack was imminent. His heart skipped a beat as he threw back the covers zeroing in on the blue contours of the puffer.

He swallowed four puffs. Breathless seconds ticked by as he cast an eye over the chaos around him. A bare mattress on the floor, piles of soiled clothes strewn amongst empty beer cans and bottles, and Molly’s collection of plastic horns: her cherished junk pile of Vuvuzelas. She had used them to scare off the roos when the shooters came. Nothing to do with protecting the wildlife, she just liked to piss the shooters off by scaring the game.

‘GET OFF THE FUCKIN SMACK’ was scrawled across an enlarged print of a decomposing, tar-sealed lung. Molly had hung the ‘Quit Smoking’ poster after she had received the summons from the juvenile court. It had been Jud’s first summons for possession. Under the black lungs, Michael had scribbled, ‘THAT MEANS YOU DICKHEAD,’ in purple lipstick.

Michael was the pretty one with long curls and pinched features. If you squinted at him, you could almost believe you were looking at a young Molly before life had become too hard.

A mound of ash piling up in an ashtray underneath the print served as a sacred vessel for burnt offerings. In a way, it was a shrine to Molly’s memory.

She had made them promise to stay in touch after she was gone, but that never happened. Just another meaningless Lidicotte family pact-like “I’ll call you after I get settled in Melbourne,” or “I’ll pay you back when I get the money.”

Happy days.

That was before Norm had become part of their lives.

Molly had enjoyed telling them how she had found Norm late one night at Milos’ Bar and Lounge. She just couldn’t resist his red neck charm and homegrown bush weed. She took him home that night, and he never left until they carried him out on a stretcher four years later. He was looking for somewhere safe to see out the rest of his life, and when he found the widow Molly and her two young boys, he knew straightaway Buchan was it. The only shame was it had taken so long.

Molly called them his dark moods. Norm was a screamer and a belter. He beat them with the sides of his fists because it didn’t leave bruises. She insisted he was a compassionate man, but Norm found his compassion in the same drawer he kept his collection of porn, bongs, and belt buckles. Seven buckles in total for every occasion from the annual bachelor and spinster’s ball in Buchan town hall to the Corryong Bush Festival and every muster, rodeo, and Easter parade in between. A quality range of high brand tools for your DIY wife-beating enthusiast.

Jud could never shake the image of Norm standing over the bed with a strap drawn tightly between his hands, the stink of stale beer seeping out of every pore. Dragging Michael out from under the covers, Norm drove his steel toe caps into Jud’s sides when he tried to stop him from taking Michael out to the shed.

When those nights came around, Jud ended up staring through the screen door at the old asbestos shed buried under brambles at the back of the house. That was where Norm kept his secret things. His man things, Molly, called them.

She warned them never to go in there. It was a death trap, she said. Norm had wired the shed himself using second-hand fluorescent lamps, and old copper wire to power the grow lamps. At night you could see the lamps flicker as Norm’s shadow moved around inside. When he was alone out there with Michael, there was never a sound other than the creaking limbs of the Blackwood tree overhead.

Jud always waited for Michael to come crawling back into bed before switching off the light. All that was left of him was a faint sobbing noise coming from the other side of the bed. Jud could feel him through the sheets, all curled up into a tiny hateful ball.

Despite everything, Molly had held true to her man.

Pop, pop.

Eyeballs were rolling across the walls when he found the sink lurking under the kitchen window. What damage could one do? One spliff a day surely wouldn’t set him off. Even better, he’d have one every second day, in which case the hour being past midnight. He was owed two.

He was up and pacing. He had to stay focused, stay clear. He had to stay away from the kitchen.

You can't work and be an addict. That’s what the doctor had said. People say you can, but you can't. If you’re functioning, working, you're not really an addict; you’re a user. You’re on the way to becoming an addict, but currently, you’re a user. You have to stop before the habit turns into an addiction. You have to stop now.

He grabbed a warm can of beer and slurped at the hole. Stay drunk – that was the solution. Get so pissed that it was impossible to form a single addictive thought.

Pop, pop.

The tension was mounting inside him. It was rising from the floor through his feet, through his legs, and into his chest. The limits were closing in all the time. He could feel it in his breathing, the phlegm on his chest foaming like a backed-up drain. A rasping cough dislodged something in his lungs. He had to do something. He needed to get away from Norm and Molly. He needed fresh air inside him, all around him.

Pop. Pop.

Grabbing one of Molly’s vuvuzela, he made for the backdoor and threw it open. A rush of cold air filled the room, scratching at the bed-soft tenderness of his skin. A mist was rolling in through the forest. Serrated mountain ridges like arctic summits rose above the homestead. Out in the fields, he spotted the shooter’s barrel mounted spotlight scanning the rise for any signs of life.

Pressing his lips against the vuvuzela, he emptied his lungs down the nozzle. A long hollow blast exploded into the valley. From the mountain ridges behind Molly’s to the opposite bank of the river, all god’s creatures scrambled for cover. Three more blasts left him breathless. He had to wait for his second wind before shouting out: “Leave them alone, fuckwit.”

The light beam flashed across the valley in search of the voice then went out.

Jud straightened up in the cold stream of air, spilling off the mountains. Standing for a few short seconds, he stared inanely at the position of the doused spotlight.

“What the fuck,” he whimpered, falling back against the screen door. He pawed at the latch until it opened and darted inside.

It was Sunday morning. The clock said 2:05 am, a whole twenty-eight hours before his next appointment at the clinic. Taking in the shade-drawn gloominess of Molly and Norm’s bush weed paradise, he wondered why he thought coming up here would help. He was already threatening the neighbors; already trumpeting warning blasts at the kangaroo mobs.

The limitations were closing in for the kill. He wasn’t going to make it past the next surge. Already he was sizing up the shortest distance to the kitchen sink.

* * * *

The small private jet followed the standard flight path descending in altitude for the final run into Melbourne International Airport. The co-pilot made the final checks and advised the passengers to fasten their seat belts before landing.

At the announcement, Leonardo’s small frame shrank even further in the broad folds of his cassock. He didn’t enjoy flying; he enjoyed landing even less. The rim of his old trilby was pulled down low to block out the glare of the cabin lights. Underneath a tired complexion spoke of hard-fought compromises. Behind quick dark eyes, he sorted his thoughts and scored a moment of silence for the grace of his soul. Out in the field, these moments were measured and brief.

Over the years, he had come to value his time alone. It was a precious commodity in his line of work, for him the most precious other than that time he devoted to his confessor. The Lord's work was a fearful business requiring a refined stay of conscience and an understanding redeemer.

Across the aisle sat a cowled figure, his head bowed in gentle reverence. He was a lowly Trappist monk elevated to the order of priesthood by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to perform the services of assistant and confessor to Father Leonardo. Having long ago taken a vow of silence, his strict adherence to that vow was brought to the attention of the Congregation. Combined with his steadfast faith in the rule of the Church, the Congregation suspended his religious duties in the Abbey of Vitreux so that he could administer to one and only one penitent, Leonardo.

Though Leonardo was a Capuchin and Brother Hugo, a Trappist in the Order of Reformed Cistercians, both men reported directly to the Promoter of Justice for the Congregation, Monsignor Mueller. There The Betrayal of Judas 10 were no loose ends, no unguarded corridors in the house of the Holy Fathers.

Leonardo had tried to sleep on the flight, but the sound of his dreams, like creaking doors, had kept him awake: Sharp fragments of life jarring together in search of reason and solace.

Removing the trilby, he uncovered a mane of silvery-grey hair. He placed it on the seat beside him and produced two bound folders out of the satchel resting at his feet. Ignoring the ‘no-smoking’ sign, he drew a cigarette from his cassock and lighting it manoeuvred the filter into the corner of his mouth.

The papers in the first folder were the property of the Congregation for Bishops, the papal institution responsible for the appointment of bishops. Under Canon Law, these documents were known collectively as the terna, a list of candidates under consideration for a vacant position in the Archdiocese of Melbourne. It was an auxiliary position soon to be vacated by the incumbent. The appointment of his successor could not be published until the Holy Father had accepted the incumbents' resignation, a decision known as nunc pro tunc – ‘now for then.’ But as the current bishop had reached the age of retirement, the matter was considered a mere formality.

On the face of it, Leonardo was to represent the Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops, but the formal request had come from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, otherwise known as the Holy Office. The request in itself was a routine practice designed to assess the character of the candidate. Still, the fact that the Holy Office had insisted on dispatching one of their own had caused a stir in Rome, which did not pass unnoticed in the far off provinces of ecclesiastical Melbourne.

Having received instructions from Monsignor Mueller, Leonardo was on the first available flight out of Rome. The Curia could no longer delay the decision of the Holy See. Divine inspiration could not be postponed indefinitely awaiting administrative approval. The governance of faith was a matter of urgency, faced as it was with growing dissent abroad and manifest corruption from within. And it was with this sense of urgency that Mueller had personally selected Leonardo to handle the inquiry. The rumours reaching the Holy Office required a special stay of conscience that only Leonardo could supply.

The second folder was given to him by Mueller. It was the property of the Holy Office, the papal institution responsible for the defence of the Catholic faith, and, more recently, the investigation of priests accused of sexual abuse. This document did not exist outside the hallowed offices of the Congregation.

Inside the folder were a number of manila files. Leonardo pulled out a black and white photo from one of the files. He held it up to the overhead lights. It was the inaugural picture of a young seminarian clutching a black biretta to his chest. It was a picture of devoted reverence as per the photographer’s instructions. The young face was gazing into the distance against a sublimely lit backdrop. It was hard to gauge sincerity with such rehearsed humility, Leonardo thought. Saintliness, like innocence, had a shelf life.

Leonardo felt the other priest close by and paused momentarily to direct the cigarette smoke away from his line of vision. He carefully flicked the smouldering ash into a small brass box. A personal ashtray gifted to him by his first confessor, which he still carried with him. Leafing through the folder, he pulled out a more recent annex to the biography and read.

‘Aloysius Van Eyck, born February 24th, 1954, in an outer suburb of Johannesburg. His parents lived by the substance of the bible and raised their family of seven in the teachings of the church. Sensing a vocation at an early age, Van Eyck received permission from his parents to apply for a scholarship to enter the St. Francis Seminary in 1971. So impressed was the Rector, the Reverend Joseph Schumann, that the admissions diary contains an inscription on the day of ‘a young man of note who should be trained for professional service.’’

Leonardo flicked to the next page.

‘Immediately after his ordination the young Father was dispatched to Rome and the residence of the Collegio dell’Anima to study at the University of the Propaganda. Before completing his studies that led to the Licentiate of Sacred Theology, he had already embarked on a course in canon law at the Pontifical Biblical Institute. He spent some years in Rome at the institute translating the Gospels of St. Luke for an edition of the New Testament, gaining ready access to the chair of the apostles and the Holy See. At this point, his career began to accelerate beyond expectation as he was chosen by the Rector of the Institute as deserving of special attention and appointed Assistant Director of Spiritual Formation at the Pontifical North American College in Rome.

But his reputation as a social innovator was regarded unfavourably by some of his superiors. His views were thought too progressive. He was known to be interested in youth movements and the new approaches to social problems that were evolving in the volatile institutions of Europe. He became increasingly outspoken in favour of birth control and the ordination of women, and was a voice for the advocates of liberation theology.’

Sighing, Leonardo skipped to the last page. Mueller’s research staff had a penchant for flowery hyperbole when it came to describing their own. In short, Van Eyck is regarded as a self-serving careerist in a vocation that demanded humility, especially in the public arena. He found what he was after in the very last paragraph.

Comments

Excellent opening

You really captured Jud's craving for a hit and painted a great picture of the rough country homestead, the roo shooters, and the isolation. You drew me in and made me want to know more.

Loved this line... "Saintliness, like innocence, had a shelf life."

Thanks Jerry. Much…

In reply to Excellent opening by JerryFurnell

Thanks Jerry. Much appreciated.