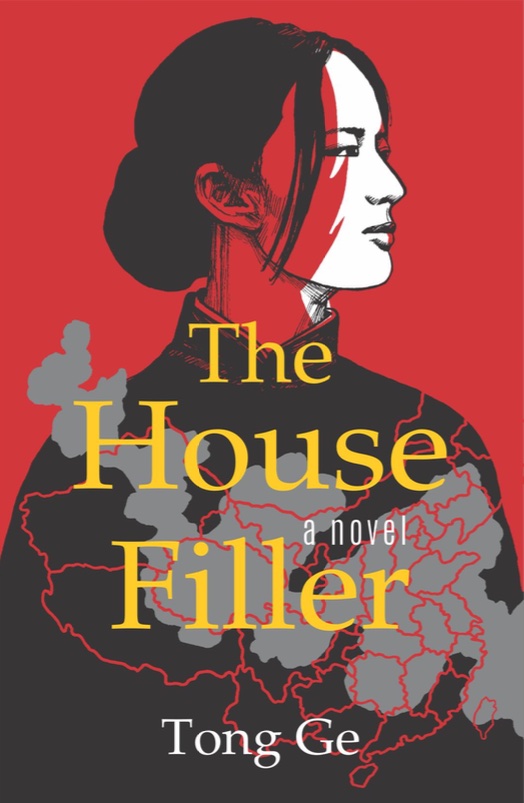

The House Filler

Tong Ge

1920–1966

Spring Review

Du Fu[1]

On war-torn land rivers flow, mountains stand.

In vernal town grass and weeds are overgrown.

Grieved over the years, flowers make us shed tears.

Hating to part, hearing birds breaks our heart.

For three months, beacon fires have burned,

Letters from home are worth their weight in gold.

I cannot bear to scratch my grizzling hair;

it’s grown too thin to hold a light hairpin.

(春望

囯破山河在, 城春草木深。 感时花溅泪, 恨別鸟惊心。

烽火連三月, 家书抵万金。白头搔更短,渾欲不胜簪。)

Peace Time

Kaifeng City, Henan Province

1920–1937

Chapter 1

I met the man I grew to love and the man I came to hate on the same day.

I had waited for that day for ten long years and lost hope of ever getting married. When most girls are married off at age sixteen, a twenty-six-year-old unmarried woman is considered an old maid. A fresh lad was out of my reach. The villagers believed my best chance was to marry a widower and become a tianfang—a house filler.

Then, out of nowhere, Father received a marriage proposal through the shop owner in Kaifeng who acted as a middleman for my opera costume-making business. However, the widower was twenty years older than me.

“Too old for you. I turned him down.” Father told me that night.

Within days, Father received a second marriage proposal. This man, also a widower, was only ten years older than me. Father met him in the middleman’s shop in Kaifeng. When Father came home, he announced, “Jinfeng, it’s decided. At least he is mature, not bad-looking and has his own business. I can’t let this one pass.”

“Did he ask…?”

“No. He didn’t ask about your feet.” Father waved his tobacco pipe dismissively.

On the day before my wedding, Father sat in our courtyard after supper. Outside, the sun turned from bright white to golden, then to the colour of fire persimmon. The typical heat wave in summer had subsided to a comfortable warm breeze. While he was cooling off with the big plantain fan, I was in the kitchen, boiling water for a bath. Throwing dry corn stalks and twigs into the belly of the stove, I pushed and pulled the handle of the bellow by the cauldron. Sweat trickled down my forehead to my cheeks and chin, then dropped onto the ground, evaporating within seconds, leaving no trace behind.

Since I was motherless, the Hu clan had sent a woman to our house and told me what would happen on my wedding night.

“You’ve seen how animals mate. It’s just like that,” she said.

Like animals? My face burned like a hot iron. I lowered my head.

“Take a bath today, for you may not have the time tomorrow. Make sure to wash your feet well, and remember, you must always obey your husband.” With those words, the woman left.

Why especially feet? Was she implying my feet were semlly? I was a bit offended. Even with the scarce water supply, I made sure to wash my feet every day. Besides, the foot bathwater was always used to water the flowers in the yard so nothing was wasted. Women’s bound feet were private in those days. The only people who had seen and touched mine were my father and the two witches who bound them. Since I was too young, he took on the daily routine of unwrapping, washing and rewrapping my feet. It was not a man’s job. With his big hands, he did it clumsily at first, then gradually got better. When I was seven, I learned to do it myself.

I closed my bedroom door, lit one single candle, and stepped into the small wooden bath basin. In the flickering shadows of the candlelight, my deformed feet looked like two pointed horse hooves. After walking for so many years on my four-cun[2] silver waterlily feet—one cun too large to be a perfect bride—I no longer felt the initial sharp pain, only the ache after a long day. I scraped my skin slowly and methodically, including the deep grooves between my heels and insteps, and wondered how women’s distorted feet were considered attractive. Most Chinese men had a foot fetish for the three-cun “golden waterlilies.” Playing with such feet gave them the utmost pleasure. All this was because of a damn emperor in the Song dynasty nine centuries ago who liked tiny-footed women.

After China became a republic in 1912, our founding father, Sun Zhongshan,[3] formally abolished food-binding. But it seemed that only some big city folks welcomed the change. I learned this from my brother Rui’s letter. Being the eldest son in our family, Father sent him to Shanghai at age sixteen. He started as an accounting clerk in a shipping company, climbed all the way up to chief accountant, married and had a daughter who escaped the torture of foot-binding. But in Henan province, having three-cun golden waterlilies was still seen as a woman’s most desirable feature. How could my husband-to-be have forgotten to ask about my feet? When he discovered my four-cun feet on our wedding night, what would happen? Would he be angry and regretful? Or even divorce me?

A whiff of tobacco smoke drifted from Father’s pipe into the room, mixing with the smell of the mud walls, the packed earth floor, the old furniture and the new clothes. The room was hot and stuffy. Our ten chicks purchased in the spring were settling down with our three hens on the roost in the courtyard, whispering their little secrets. The moonlight grew brighter, casting swaying tree shadows onto my paper-covered latticed window. A crow’s caw startled the night. A bad omen. Hopefully I’d see magpies the next day; they were always a good omen.

“Go to bed early. You’ll have a long day tomorrow,” Father shouted from the yard. I heard him knock off the ash from his smoking pipe and saunter into his room, then shut the door.

I had a hard time falling asleep. A mosquito had got into my mosquito net, but I couldn’t find it. It drove me mad. Finally, I took the net off the ceiling, balled it up, and threw it to the corner of the bed. The mice were also particularly noisy, running on the ceiling as if they were fighting or having a wedding procession.[4] Would my husband be nice to me? What did he look like? What kind of people were my parents-in-law? All mothers-in-law were mean. As the Chinese saying goes, a daughter-in-law is made by beating just as dough is made by kneading. I only hoped I wouldn’t be kneaded too hard.

When I finally drifted off, I dreamed of my wedding night. My husband, upon seeing my feet, cried out, fell off the bed and became a big scary mouse. I woke up in a fright and could no not fall asleep again.

Chapter 2

When the rooster crowed for the third time, I dragged myself up and began to make breakfast: millet congee, re-steamed buns, pickled cucumbers and white turnip. I gulped down a bowl of congee and a bun, as I knew I wouldn’t have time for lunch.

The women from the Hu clan arrived. They removed the fine hairs on my face with thread, combed my hair and perfumed it with osmanthus oil, and coiffed my long braid into a bun behind my skull, securing it with a silver hairpin—the only item I’d inherited from my mother. Long braids were for maidens; buns were for married women. Not long ago, Chinese men also wore long pigtails. When the revolution came, the Qing dynasty was no more, and as citizens of the new republic, Chinese men were asked to cut off their pigtails. But it was hard. For many of them, losing their braid meant losing their dignity. Other men kept their braids out of loyalty to the old royal family or fear of Qing’s army’s return. One day, my father went to Kaifeng and bumped into a group of students who were hunting down men with pigtails. Father was pinned against a wall as they cut off his braid. Afterward, he covered his head with a dog-skin trapper hat for months, ashamed to let anyone see his new hairdo. Fortunately, it was winter.

Thinking of this, I chuckled involuntarily.

“You're supposed to cry your eyes out on your wedding day.” An auntie gave me a light shove. Normally brides cried when they were about to leave their beloved parents behind. A laughing bride could be seen as heartless and improper. But those girls were sixteen and seventeen. To a twenty-six-year-old, getting married was a huge relief. Still, I knew I needed to be reserved and serious.

While the women helped me with makeup, my thoughts drifted to my mother, who died giving birth to me. I had learned from my brothers that my mother died before having a chance to feed me even once. During the initial days, the new mothers in the village took turns nursing me. Later, Father bought a goat to feed me its milk. When I was a bit older, Father made millet gruel and wheat flour congee for me, and even added smashed egg yolk from time to time. He was the one who changed my diapers, bathed me, taught me to walk and talk. After my brothers left home, I was the only child at my father’s side. Now, in less than twelve shichen—twenty-four hours in western time—I would depart the only house I knew and leave my father forever.

“Don’t cry now! You’ll mess up your makeup,” scolded a woman helping me. I quickly dabbed away my tears and looked at myself in the mirror, taking in my face—double eyelids, thin curved brows, and thick lips—all seen as good features in Chinese culture. But I also had an angular jaw and a darker complexion. In Chinese face reading, thick lips mean honesty, but they can also mean being simple, naïve, and too trusting. The ideal beauty for a Chinese woman is a duck egg-shaped face. An angular jaw means being upright, reliable, and confident, but for women, it can also mean being stubborn. I didn’t think I was stubborn. In fact, I had been a perfect daughter, always obedient to my father. I upheld the Confucian teaching of the Three Obediences: a woman should obey her father before marriage, her husband after marriage, and her son after her husband's death. If only my jawline were rounder and softer, and my skin lighter, I would be considered beautiful. Chinese believe that one fair skin covers up one hundred uglinesses. But my biggest flaw? My feet. They were too big, too noticeable—something to be ashamed of, something that should be hidden. To make up for it, I had to lean on my strengths—my needlework, my good heart, and my diligence—to win over my husband and in-laws.

On my bed, my wedding clothes were laid out: a Chinese-style blouse with a slanting line of cloth-knots on the right side for buttons and a pair of pants, both made of red silk. As a seamstress, I added my special touch by embroidering lacework in golden thread on the high collar, sleeve and trouser cuffs. I also made my own wedding shoes with a smiling brocade golden phoenix embroidered on the vamp. The design was my favourite because my first name—Jinfeng—means golden phoenix.

The women chirped like sparrows.

“How lucky you are, finding a man in Kaifeng.”

“Look at those wedding clothes. You made—”

“We country bumpkins can't ask for more.”

“Once you’re gone, who do we go to for embroidery patterns?”

“I heard he is a tile flipper, has a big house—”

“Aiya! You stepped on me!”

“As long as he lives with his parents, the house is not—”

“If you want to earn his family’s respect, have a baby boy.”

“If not, he may get himself a second wife.”

……

My brand-new white muslin foot-bandages were neatly wrapped around my feet. I had a red scarf ready to cover my face when arriving at my husband’s house. No one there was supposed to see my face until the groom took the scarf veil off.

It would be the first time we saw each other.

The departure time came. Tradition required my going there alone. As I stepped outside of my room, I saw that the entire village had come to see me off. Weddings and funerals were always a village affair. Everyone would show up unless the family had enemies. Father had no enemy, and I sure hoped I wouldn’t end up with any either.

A hen clucked proudly. She must have just laid an egg. The Chinese date trees were blossoming with little yellow-greenish flowers. In just a few months the dates would be ready for harvesting. Father’s potted flowers also bloomed vigorously in the yard. Once I left, he would have to rely on selling those flowers—not much of an income. Father had sold the few mu[5] of land we once owned to pay for my brothers’ schooling shortly after my mother passed away. The room against the east wall looked shabby. It was once the boys’ classroom. After Rui left home, my other brother, Yu, didn’t want to study anymore, so Father let go of the tutor and turned it into a storage room.

Firecrackers ignited noisily. Kids covered their ears with their hands. Red and white confetti littered the ground. Dogs barked and babies cried. The acrid gunpowder smell overtook the sweet scent of the flowers in the yard.

I put on the veil so that no stranger could see my face as I was helped out of our courtyard and into the bright red palanquin carried by eight men, and we took off. An eight-carrier palanquin was typical maiden becoming a first wife. Even though I was a house filler, the groom had agreed to do this for me. The palanquin creaked as if singing a happy tune. A group of musicians playing trumpets led the procession, followed by eight more men carrying four trunks of my dowry. In other provinces, a man had to pay a bride price to get married. Not in Henan. Here, the bride needed a dowry to be married off. The larger the dowry she brought with her, the more respect she would get in her husband’s house. I had seen ten trunks of dowry from rich brides and none from poor ones. According to the old folks in the village, during a famine, a girl being sold for a sack of grain was not uncommon. In many cases, they ended up in whorehouses.

I was required to cover my face even inside the palanquin, but the moment the palanquin’s front curtain was lowered, I took my veil off. As the noise behind us trailed off, I opened the side curtain a crack and peeked back. Father stood on raised well platform at the edge of the village, one hand shading his eyes, looking in my direction. At age sixty, his hair had turned white. Once I left home, he would have to fetch water from the well, cook and clean all by himself. He could have kept his sons at home, as most villagers did. But he wanted them to have a better life so he sent Rui to Shanghai. As for Yu, Father couldn’t make him study or work, so he sent him to live with Rui, hoping big brother could lead little brother to the right path.

The musicians had stopped playing their instruments. No need to make a show on an empty country road. I peered out from a gap of the curtain. It was June. The sun baked the earth. The wheat field had turned yellow, the kernels heavy and the ears bent low. The smell of harvest was in the air. Sweat dampened my clothes and I felt parched and suffocated, just like the last time I was stuffed into a palanquin when I was nineteen.

[1] Du Fu (712–770) was one of the most outstanding poets in the Tang dynasty. The poem is translated by Xu Yuanchong and modified by Tong Ge.

[2] 1 cun = 1.31 inch

[3] Sun Zhongshan, (1866–1925) also known as ]Sun Yatsen or Sun Wen, was a Chinese statesman, physician and political philosopher. He served as the first provisional president of the Republic of China and was the first leader of the Nationalist Party of China. He is widely regarded as the Father of the Nation in the Republic of China and the Forerunner of the Revolution in the People’s Republic of China for his instrumental role in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty during the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912.

[4] Mice getting married is a common theme in Chinese fantasies and folktales.

[5] 1 mu = 0.16 acre

Comments

There is no need for any…

There is no need for any device to hook the reader since the entire excerpt is totally engaging from beginning to end: the characters, the setting, the dialogue, the background, the anecdotal material that serves to embellish and delight. The voice of authenticity rings loud and clear, and carries the narrative along on a wave of power and intrigue. Excellent writing.

Very well described scenes…

Very well described scenes. Great work with dialogues.

Very well-written. Great…

Very well-written. Great dialogue as well.