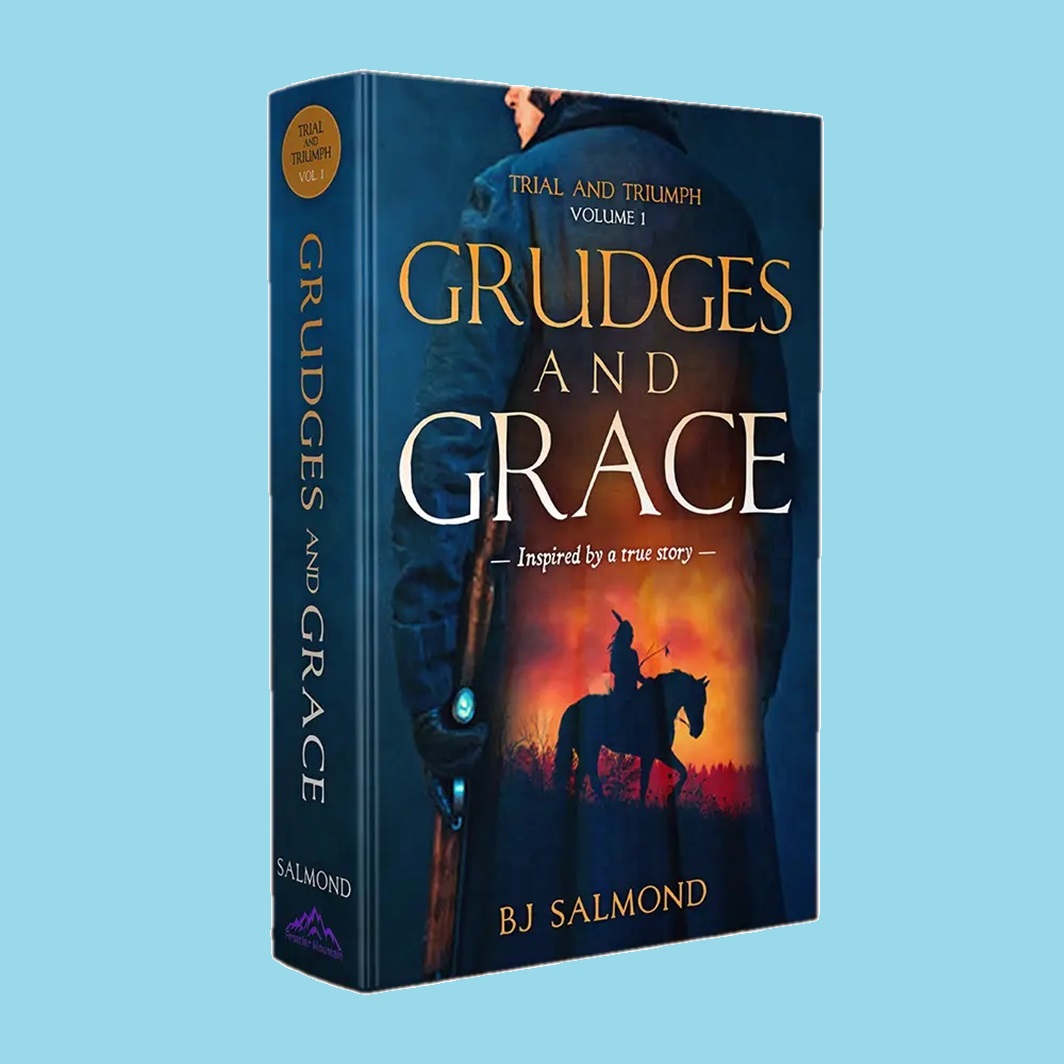

Grudges and Grace

Chapter .5

Discovery

Jefferson brought the chair down hard against the wrought-iron stove. Splinters of wood flew in every direction.

His stepfather had just left the house but came running back in when he heard the loud noise through the front door. As he surveyed the scene all the muscles on his face tightened. He saw Jefferson holding the remains of the chair. “What do you think you’re doing?”

Sarah, Jefferson’s mother, quickly intervened to calm her husband, then turning to Jefferson said, “Go to your room, now.”

Jefferson dropped the pieces of the chair that were still in his hands and went straight to his room. He could hear Jean yelling at his mother about what he had just done, upset that she wasn’t letting him take more severe action. Jefferson slammed the door to his bedroom, stomped his way to his bed, and flung himself onto the mattress.

“Jefferson Chestnut Slade! Don’t you dare slam doors in this house,” his stepfather shouted.

He heard his mother talking to his stepfather, unable to make out what she was saying. Then he heard her forcefully say, “Just let me talk to him first.”

After a few moments, the door opened a crack, and a soft knock followed.

“Go away!” Jefferson called out.

He heard the voice of his stepfather from across the house, “Don’t you talk to your mother like that.”

“Jean, please let me handle this,” Sarah called back as she walked into the room, shutting the door behind her.

Sarah pulled a chair next to the bed and sat down. She stared at Jefferson in silence, considering how best to help him.

“Jefferson, blowing up about what your father told you and smashing the kitchen chair to pieces is not going to make things any better for you. You need to control your anger.”

Jefferson scrunched his face. “He is not my father.”

“He provides for you, feeds you, gives you a bed to sleep on, and a home to live in. He is your father.”

“I can’t stand him,” Jefferson said, his speech hurried and strained. “I try to do what he asks, but every time he sees me, he wants me to do another chore. I never get to play, then he whips me when I try to do something fun. I hate him.”

“He’s just looking out for you. You can’t get into much trouble when you’re working.”

Sarah tried to meet his gaze and smiled. Jefferson folded his arms and stared at the floor, refusing to look at her.

Sarah touched his knee. “Come on now, other ten-year-old boys have just as many chores.”

Jefferson raised his voice. “Then how come they’re always outside playing, and I’m always working?”

The voice of his stepfather boomed from the other side of the door. “Don’t you raise your voice with your mother.”

Sarah lifted her eyes to heaven and in a sweet voice said, “I’ve got this, dear. Please let me talk to him without interruption.” She looked at Jefferson. “Jefferson, those boys out there playing, likely put their shoulder to the wheel and got all their chores done.”

“Well, Jean is just plain mean, and I hate him.”

“Maybe you wouldn’t hate him so much if you tried doing what he asks of you,” Sarah said, speaking slowly and deliberately. “He wouldn’t be as mean, and you would be a lot happier.”

Jefferson was silent. Sarah considered her son for a moment. She saw the anger in his eyes. Her heart ached to see him like this. She came to a decision. She opened her mouth to speak, but no words came out. She closed her eyes, swallowed, then pressed on.

“You know, my father struggled in much the same way. Not with his father, but with his anger.”

Jefferson blinked, and his jaw dropped. “You’ve never mentioned your father before.”

Sarah glanced down, her eyes moistening. “I lost him in the most painful way. It is hard for me to talk about him without remembering that awful day.”

Jefferson had never heard about any of his mother’s immediate family and was eager to hear more. He spoke softly. “What was he like?”

Sarah noticed the change in her son’s demeanor and smiled. She looked at her hands, then wiped away the tears that threatened to spill down her cheeks, “His name was William Albert Chestnut.”

Jefferson’s eyebrows rose. “That’s why my middle name is Chestnut.”

“Yes. He grew up on a farm, but he didn’t like farming. He was finally able to get out of it when he had an accident with his horse.”

Chapter 1

First Shot

St. Louis, Missouri

April 20, 1832

The horse fought against the reins as William tried to get it moving in the right direction.

“Move, you dumb animal!” he hollered.

He had to finish getting this field plowed in the next few days, but at the rate he was moving, it would take weeks. William set down the plow and walked over to the horse so he could look it in the eyes. “Come on!”

William slowly shook his head, then in a softer voice said, “I can’t get this done without you.”

He grabbed the reins and gave them a hard tug. The horse resisted and pulled against him. William pulled harder but to no avail. Finally dropping the reins, he walked back toward the plow. As soon as he passed the horse, it turned a little and kicked. William felt a sharp pain as the hoof rammed into his side. The air completely gone out of him, he fell to the ground. William struggled to breathe for several agonizing seconds then everything went black.

~ * * * ~

William opened his eyes. He stared at a white ceiling. A soft, plush blanket covered him, and a cushy, down mattress pressed against his aching body. His mother sat in a chair by his bed.

She put her hand on his forehead, testing his temperature. “St. Louis boys weren’t meant to fight horses.”

William moaned. “I don’t want to farm anymore.”

William’s mother blinked, and her lips parted, “You no longer want to work for your father?”

“It’s not working for Father that I don’t like—it's farming. I’m no good at any of this . . . besides, Wilford died plowing, and I almost suffered the same fate today.”

The image of his brother collapsed on a plowed field forced its way into William’s mind.

His mother’s eyes dropped. “You and your older brother were very close. His death was more getting sick from the ague, and him ignoring it than from plowing. Even so, I can see how that memory would turn you away from farming.”

“What I really want to do is own and run one of those mercantile stores.”

William’s mother stared into his green eyes. “I know you keep talking about that. You are twenty now. Perhaps it’s time for you to explore that option. I’ll talk to your father.”

“Thanks, Ma!” William tried to sit up and hug her, but as soon as he moved, the pain in his side reminded him that he should stay put.

William’s mother ruffled his thick, brown hair, and she admired the light freckles on his face and arms. “Right now, you need to save your strength and stay down. The doctor said you cracked a rib and have some nasty bruises. You need rest so you can heal.”

“All right.”

As his mother left, William gazed out the window. He saw his father’s prosperous farm and the hired hands finishing the work he had left undone. Tall stalks of corn had grown there the previous year. His father tried to teach him how to plow the field that year. He made it look so easy, but William was more accustomed to taking care of the animals. His father had told him that he could plow this year. William hadn’t looked forward to it, but he didn’t want to let him down.

William’s father had been able to sell much of what they grew in the St. Louis market. The city had three miles of riverfront, and was where the Missouri and Mississippi rivers converged. Because of this, ships of all sorts were regularly stopping at St. Louis to drop off passengers and to resupply. It was the last major city in which anyone headed west could get needed provisions for their journey.

After the death of their firstborn, William’s parents devoted more money to helping him. When he turned twenty, his parents had given him his own horse and wagon.

As William lay resting on his bed, his father came in. “How are things going, Son?”

“Good. I haven’t seen you in a while.”

His father sat down on the chair by the bed. His plump cheeks puffed up as he blew out the air, then he rubbed his thick mustache in thought. “I’ve been busy talking to Governor Dunklin. He wants to start up a standardized public education system in Missouri. But I think it will kill the free-market education, making it a slave to the whims of the government and a select group of people who think they know what’s better for our children than we do.”

“You going to try to get him voted out?”

“Maybe.” His father stroked his chin. “A fellow by the name of Boggs seems eager to take his spot. He might have some promise.”

William’s father always liked to meddle in politics. When William was nine years old, President James Monroe began his second term in office, and Missouri had just become a state. He remembered that his parents left home to celebrate frequently during that time, leaving William in the care of his nanny.

When he was sixteen, his father kept going on about the Democratic Party, a new political party that had recently formed. William didn’t care much for politics except once when, in that same year, the war hero, Andrew Jackson, became President. William was excited about that, as he had grown up on stories his father had told him at bedtime about how “Old Hickory” drove the British out of our country and saved the nation. William figured someone like that deserved to be the President of the United States.

~ * * * ~

After several weeks, William was feeling much better and was finally able to walk around. He heard the cook call out that dinner was ready and made his way downstairs to eat.

After his father blessed the food, as he did every meal, he looked at William. “How are your ribs feeling?”

“Hurts if I move the wrong way, but otherwise I’m feeling a lot better.”

“Your mother and I have been talking. I know your heart has been set on owning your own store for some time now. I was hoping you’d take to farming and run our farm someday. But I’ve been thinking that maybe I ought to let you spread your wings a little. I’ve decided—”

Williams’s mother cleared her throat and stared at her husband with raised eyebrows.

William’s father looked to his wife, then back to William. “Excuse me—we’ve decided that if that’s what you really want to do, we’ll support you. I’ve talked to Andrew Burnham, who owns Burnham General Store in town, and he is willing to take you on and teach you the business.”

William’s eyebrows shot up, and he smiled from ear to ear. “Thanks, Pa! That is so macaroni! I can’t wait. When does he want me to start?” He sat up straighter and instantly regretted it, flinching with the pain.

William’s father lifted his chin and creased his brow, “I told him about your injury, and he said you can start just as soon as you’re all healed up.”

Chapter 2

Last Straw

By the time William turned twenty-one, he had eight months of clerking experience behind him. His father surprised him on his birthday by getting him his own shop and giving him a loan so he could buy the goods he would sell.

William was able to keep his store going successfully for three months. He even paid his father back some of what he had borrowed for the start-up costs.

In the fourth month, the business started struggling. The bank gave William a few loans to keep his store stocked, though his business continued to fail. William felt compelled to go back to the bank and ask for another loan.

The banker shook his head at the request. “I hope you understand, Mr. Chestnut, I’m hesitant to give you any more loans until you’ve paid back what we’ve lent you already. Why do you think you need more?”

“I have more than a few customers who are not paying their accounts. I just need one more loan until I can get them to pay me back. I’ve also had a problem with theft, but I’ve rearranged my store. Now I can see anyone who tries to slip something away while I’m at the register.”

“I’ve been to your store, Mr. Chestnut. I like to shop around and compare prices, and I’ve noticed that your competitors are selling what you do for a better price. Just some friendly advice: you may want to price your goods a little more competitively.”

William looked at the ground and bit his lower lip. “I have noticed that, but there is not a lot I can do about it if I want to make any profit at all. I don’t know how they get away with selling things at those prices. I’d be out of business if I sold goods at those prices.”

“From what you’ve told me, that may happen anyway.” The banker shut his book. “I’m sorry, Mr. Chestnut, I just can’t afford the risk of giving you another loan. If you can’t pay your debts by the end of the month, I’m sorry to say that we’ll be forced to foreclose and confiscate your store and your assets to pay your debts.”

William could feel the blood rushing to his head. He tapped his thumb on the desk and narrowed his eyes. I don’t have to listen to this.

William grabbed the papers on the desk and threw them into the air. Papers rained down around them. The banker tried to seize him, but William dodged, and pushed the banker out of the way, sending him flying head first into a desk. William left the bank, slamming the door behind him.

~ * * * ~

A week passed, and William’s situation hadn’t improved. He had to pay a large fine for what he’d done at the bank. He knew he should not have reacted the way he did, but the banker had made him so angry.

He walked down the street, his hands in his pockets, his head down. He stopped in front of Burnham General Store. The familiar yellow sign that advertised the store’s name stared down at him. William remembered when he looked forward to seeing that sign. Now it represented the mean-spirited man who oppressed his ability to thrive in this business.

As he walked into the store, the familiar, musty smell of dry goods greeted him. Mr. Burnham sat behind the counter giving change to an old farmer. Two other men milled about the store, critically eyeing the goods. After the old farmer left, William approached the counter.

Mr. Burman’s lips went tight, and he nodded in greeting. “William.”

William slammed his fist on the counter. “Why are you working so hard to drive me out of business? What did I ever do to you?”

Mr. Burnham considered William for a few seconds, then smiled. “You opened a store and drew away my customers. So, I decided to compete. A little competition is healthy. Drives free enterprise forward, you know.”

Then, looking into the sour expression still on William’s face, he leaned his body over the counter and whispered, “If you can’t handle the plow, then stay off the field, Mr. Chestnut.”

William thought of his brother, who had died while plowing the field, then of his own failure at plowing. William looked at Mr. Burnham through silted eyes, then hit him in the jaw.

Mr. Burnham stumbled back, eyes wide. He shook his head, and quicker than William expected, came around the counter and hit William square in the forehead. The blow sent him reeling back into the shelves. They toppled like dominoes, goods of all kinds lay strewn across the floor.

William got up and charged straight for Mr. Burnham. Just before he could make a connection, the two other men in the store grabbed him.

Mr. Burnham rubbed his jaw. “Hold him tight, boys, while I go for the sheriff.”

~ * * * ~

William stood in front of the judge, waiting for him to speak. The judge ran his fingers through his black, curly hair, then licked his finger as he thumbed through the papers in front of him. He glanced up.

“Well, let’s see . . . we have William Chestnut here. I would say welcome back, but a court is not a place where one should feel welcome.” Pointing at William, he said, “You shouldn’t be wanting to come back after even one visit. So why is it, William, that this is the sixth time I’ve seen you in this courtroom?”

William stared at the judge, his lips tight and his brow lowered. “Judge, none of those were my fault.”

The judge raised his eyebrows. “No? Well, let’s go through them, shall we?”

Comments

Family Histories are a treasure trove of story inspiration

I really enjoyed this. As a former Utah resident of 15 years and genealogist myself, I can relate to the joy and inspiration found in exploring our ancestry. Nice job translating it into a novel! Good luck in the competition!