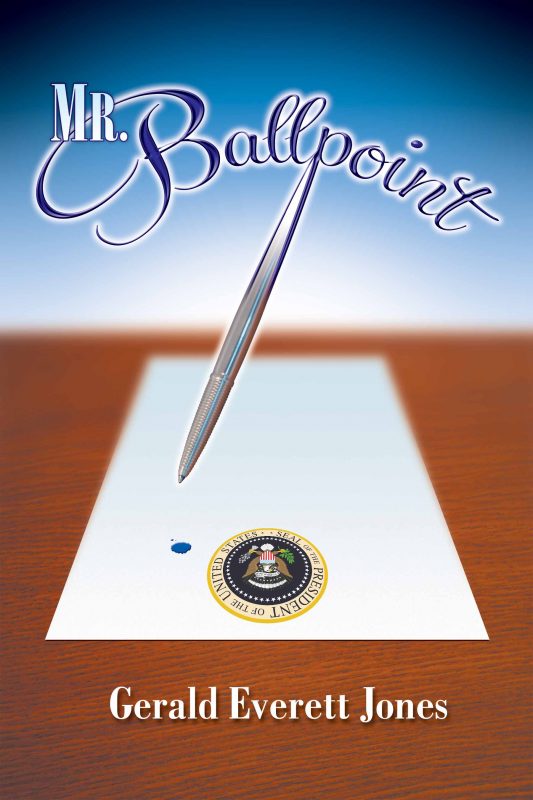

Mr Ballpoint: A Novel

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

Sometimes you wonder how a thing started. The ballpoint pen, for example. Everybody has one. Nowadays they’re so cheap they’re throwaways, like disposable razors. But time was, they were a luxury item, an expensive gift for that white-collar executive in your life who was on a rocket-ship ride to the top.

My name is Jim Reynolds and, seriously, I was trained as an engineer. I should have stuck to that. I really should have. All joking aside.

So there I was in May of 1947, standing just outside the Oval Office. Yep, the one that’s inside the White House. Where else is there an oval office? There’s a novel idea. I really wonder if there’s another one somewhere. I mean, the President doesn’t exactly have a patent on the idea, right?

It was amazing to be there for a lot of reasons. Mainly, I thought it was impossible because the President must be an incredibly busy guy, and even though the war had been officially over for awhile, helping Europe rebuild and keeping a careful eye on the Russians no doubt took up a lot of his time. Even after we had the appointment set with him, I wondered whether we’d be able to meet at all when I read in the paper that the White House was undergoing renovations. They’d moved the Trumans over to Blair House across the street, and I worried that if we were so lucky as to get in front of him, it might be in a hallway somewhere for about a minute. But it turned out that the Oval Office itself was still open for business every day. While work on the residence was going on, Mr. Truman and Bess slept over at Blair House, and the Secret Service took him back and forth each day to his office.

Anyhow, I was standing there because I was too nervous to sit. And I was there, not because of anything I did, not really, but because of what my father did. Or didn’t do. Or didn’t necessarily mean to do.

It’ll take awhile to explain.

So seated behind the desk in front of me was Winifred, President Truman’s personal secretary. She wasn’t much of a looker, but then you wouldn’t expect her to be. She was friendly enough, extremely well done up I should say, but she came across as efficient and no-nonsense. You’d know he’d have insisted on that, if you knew him, which I didn’t. I didn’t even vote for him later in ’48, but that’s another story, too.

Winifred was one of those iron-fist-in-a-velvet-glove types. Sweet, sincere smile, but she could cut you like a razor. Truman was running behind on his appointments that day, not a situation I thought she’d have approved of, but I’m sure she managed it well enough, with him being about as stubborn as a Missouri mule, or so they said. Didn’t make me any more calm about meeting him, that’s for sure.

“How much longer, do you think?” I asked her.

“Oh, just a few minutes,” she said. “He’s just signing a bill.”

A lump came into my throat. I was nervous enough already, but the next thought I had terrified me in all kinds of new ways.

There must be a lot of dignitaries in there, including members of Congress. Reporters, too, for sure. Way to fail — in front of a crowd! Would he invite any of them to hang around after he asked for us to be shown in? Was there maybe another exit so they wouldn’t all stampede through here? If not and they poured out, should I be standing or sitting? Sitting, it seemed to me, would be a good plan, and don’t stick your legs out.

“He wouldn’t, ah, use a ballpoint to sign anything important, would he?”

She gave me the oddest look. And just then, I realized I hadn’t urinated for about four hours.

“Ah, you got a restroom?” I asked.

She gave me one of those silent, angled-wrist directions which indicated the general route to the toilet. I assumed the Secret Service would be following me, but I didn’t mind. You have to do what you have to do. I bet lots of people have that problem right before they march into the Oval Office.

So I was at the urinal, about to let fly, and of course that’s when you relax whether you want to or not. My mind popped right out of the moment, and I remembered that other time, the much more momentous time, at least from my personal viewpoint, when I was doing the same thing, right before that other big thing in my life came in on a whirlwind.

~~~

So it was late May of 1944, and I was at the urinal in the student union at Stanford. Not a worry in the world, mind you. I had all my credits. I was going to graduate. I was a little concerned about what came next but not overly so. It wasn’t a bad feeling at all.

I just started to let fly and this guy Dirk Davis glided into the stall next to me. Now, I didn’t know him. Not really. I did know him by reputation. He was on the football team, which I definitely was not, not really. I was a cheerleader, and that, too, is another story. But I certainly knew of him, and although he wasn’t strictly first string, he was a force. A force to be reckoned with. That much, I knew.

He had those chiseled good looks. You know the kind. He could probably whistle and have anything, was my thought.

So as he — oh so nonchalantly — started pissing a rope, he began to chat me up.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” I said back, pretending it was no big deal talking to him in this casual way, even though my stream was barely a trickle at that point. I wasn’t the only male cheerleader. It was kind of a tradition. But you never knew what some other guy was going to think about that. Especially a guy on the team who maybe thought of cheerleaders in short skirts as some kind of snack you have before the big game.

Was that a chuckle? Can it be you don’t think much of male cheerleaders? Well, let me tell you, and here I am getting seriously ahead of my story, I got a U.S. president elected because of my cheerleading ability. Bear with me here. It was 1952, after a lot of this story takes place (but not before it ends), and I was on the dais at the Republican National Convention at the International Amphitheater in Chicago. It was a foregone conclusion that they would nominate Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the war hero, for their presidential candidate. But the convention was deadlocked on the decision about who his running mate would be. To make matters more interesting, this was to be the last “brokered” convention — where even the big deals get negotiated in backrooms. That’s because it was the first convention to be televised, and after that, the public had to see for themselves how roll-call votes by state determined the outcome. So there I was, an enthusiastic supporter of Ike’s, and here was this big crowd on the floor in front of me with nothing to do because some cigar-chomping pols in the back room were still arguing about the VP nomination. So one of the bigwigs, who knew of my career at Stanford, said, “Lead ’em in a cheer, Jim.” So I got up, and for a solid half-hour I roused the crowd in yelling, “I like Ike!” over and over and over and over again, until the deal in the closet got done. In the end, Richard M. Nixon, the senator from California, was nominated from the floor unanimously. And then, of course, he went on not only to serve as VP but also as president, after losing to JFK and then staging an amazing comeback, only to end up resigning as a result of the Watergate scandal. Now, think what you want about whether I should have stayed in bed that day in 1952, but I have a letter on White House stationery from Nixon when he was sitting there in the Oval Office where Truman is at the beginning of my story here, thanking me for making it possible for him to be elected to the highest office in the land.

Don’t believe me? Watch the movie MacArthur with Gregory Peck. In it there’s a news clip from the convention. Watch very carefully because it’s only a second or two, and you’ll see me leading that cheer.

But I digress. Back at the old urinal, I obviously didn’t know my own strength. In fact, I was pretty intimidated by this second-string fullback. But it gets better (actually worse, then better).

“Damn,” Dirk said, “it feels good.”

I was thinking he’s an animal, chatting about his bodily functions, but I wasn’t going to say it.

“You said it,” I said.

He laughed. “Graduation, I mean.”

“Oh,” I said, glad that he wasn’t rhapsodizing on the joys of taking a leak.

“Know what I’m going to do?” he grinned, looking over at me as if he’d won some kind of sweepstakes.

“Engineering?” I replied, thinking it was as good a guess as any.

“You bet,” he said. “I’m going to get a job at Hughes Aircraft and propose to Zelta Burrows.”

Panic! Red alert! Battle stations!

I’d voided about half my bladder, but there was no time to lose. I stanched the flow, zipped up, shot him a manful grin, and got out of that restroom in a hurry.

I found Zelta in the dining hall bussing tables. She didn’t look particularly surprised to see me.

Hoo boy, she was beautiful.

“Zelta,” I said, breathless. “I know we said we’d take our time and not necessarily get serious right away, but will you marry me? I need an answer immediately.”

I have to say I did do a good job of selling her. Too good, actually. After that, she was worried I’d turn out to be just like him — my dad, the silver-tongued devil.

~~~

Let’s just say he didn’t make it easy for her.

The day we got married was eventful and memorable, and the things I particularly remember I wish hadn’t happened. Such is life.

We decided, or she planned and I agreed, to hold the ceremony in the backyard of her parents’ home in Pasadena. What with the war and the general austerity, people didn’t spend a lot on those kinds of things back then. Her father was a doctor, and they had a pretty nice place, and the back lawn was about as lush as those English gardens you see in magazines, so a person could do a whole lot worse.

I was standing with the minister and a gawky maid of honor I hadn’t met, underneath a flowered trellis. The thing was supposed to have started some time ago, but as they say in the theater, we were holding curtain for late arrivals.

Meaning my mother and father, who were supposedly on their way in a taxi from the airport.

They were winding up one of his business trips to South America, stopping in Cuba on the way back. There was a time he used his own plane for these jaunts, but thankfully for the sake of my mother’s willingness to accompany him, he’d sold it years ago. Even now that he had to fly commercial, he still wanted his own plane. Fool that I was, I thought it would never happen.

I didn’t call him Dad, by the way. I called him Milt, as everyone else did. Milton Reynolds was a legend in his own time, even before he was a legend for the pen and all the rest. He just got out of bed that way, believed it, and the world never contradicted him.

I found out later that he was giving the cab driver directions, and all the wrong ones. He’d been in Los Angeles on sales trips about a thousand times. After all, Gottschalks had stores here.

From my vantage point under the trellis, I could see Zelta primping on the back porch of the house, ready to take her father’s arm and be led down the grassy aisle. Dr. Monty Burrows was a heart surgeon, a decisive man, and he was not accustomed to any manner of hesitation. When it was time to cut, dammit, he cut. She told me later how it went.

“Zelta,” he said. “This man Reynolds is a…”

“A what?” she shot back.

“A…salesman,” he spat out. “They say he’s made an ungodly amount of money. In wartime.”

There were people supposedly making fortunes selling watered-down penicillin on the black market. A doctor would not approve of that, of course. But Milton was not in that category at all. I mean, maybe he was a bit agnostic about the rules, but he wasn’t breaking any laws. At least, I didn’t think he was. Not back then.

“I don’t care what his father does,” she huffed. “Jim is an engineer.”

It was about then she peeked around the bushes and beamed reassuringly at me. We exchanged a pantomime kiss as Monty smirked. I gave her the old spiral-wrist thing as an indication to hurry up. No use waiting for Milt, was my opinion.

Taking her cue from me, she told him, “We can’t wait forever. Let’s go.”

Monty gave the high-sign to his wife Flora, who cranked up the old Victrola and dropped the needle on a scratchy wedding march. It was beautiful, and I actually choked back a tear or two.

“Son of a salesman is a salesman,” Monty quipped to her sotto voce as he led her toward me. “Mark my words.”

She should have. She really should have.

~~~

We were duly hitched. It took about ten minutes. And we didn’t spend much time chatting with the folks in the house.

About a dozen or so guests threw rice as we ran out toward a decorated Chevy coupe at the curb. We’d planned to spend the night at a little rented cabin in the mountains above Malibu. I mean to tell you, I couldn’t wait. In my natural anticipation about what came next, I naturally forgot about Milt. It wasn’t that I didn’t care, but I knew we’d catch up with him sooner or later, and he’d have the last word, as usual. Something clever to say, all charm, as if missing my wedding was no more than a blip in the flow of time. Which, if you took the long view, it was, more or less.

But right then a cab pulled up with a screech.

Milt jumped out, ran straight up to Monty, and thrust out his hand.

“Dr. Burrows, sir,” he said, and I had no idea how he knew which guy because they hadn’t met until now. Then he turned beaming to Flora, getting it right again, and starts in, “And you must be—”

“— Late,” Monty snapped.

There was a long moment of painful silence. Too long. My mother, Edna, appeared at Milt’s side. The cabbie was right behind her, pushing a cart loaded down with luggage and a case of liquor.

Spying the case, Milt said, “Let’s all have a drink!”

Monty saw it, too, something only a bar owner would recognize in wartime, and asked, “What have you got there?”

That was Milt’s cue. Ice officially broken. He threw an arm around Monty’s shoulders and led him back into his own house like he was the host.

Zelta and I had retraced our steps, joining the crowd as they headed back in.

“The finest Jamaican rum, my good man,” Milt said. “Little wedding present from Juan Batista. What a guy. Did you know we’re just in from Havana?”

I had Zelta by one arm and Monty took the other.

He asked her like a poker player throwing down his winning hand, “Happy now?”

As Milt must have figured, it didn’t take that group long to guzzle up enough of his expensive rum to get a party going. I don’t know how many of them had planned to stay, but they all did, sure enough.

After everyone was nicely lit up, I don’t know whose idea it was to start a game of charades. I do remember Milt’s performance. Vividly.

He pantomimed a movie reel, thumbed a hitch-hike, then fanned his butt with his hand.

They were all stumped.

All but Zelta. “Gone with the Wind,” she sighed.

“That’s my gal,” Milt said, jabbing his fist at her. “Smart as a whip,” he said, turning to Monty. “You didn’t waste your money on Stanford.”

Monty beamed back, and this time it was genuine. He knew he had fathered the school’s prize catch.

I’d had plenty to drink, but I wasn’t caught up in the fun. I was wondering when that moment would come when I wished to be anywhere else but here. Milt strolled over and took my arm, drawing me aside.

“Jim, boy,” he cooed. “Cheer up. You’re getting lucky tonight.”

He was right about that, I still had reason to hope. But then, I didn’t want to give him the satisfaction.

“What’s the matter?” he asked. “The plane was late, the cabbie got lost, but you got a gorgeous gal and everybody’s fine!”

It took me awhile, but eventually I got out, “They all think you’re…some kind of…I don’t know…huckster.”

“I am!” he bellowed. “And proud of it.” Then he added, “And you’ll be better than me.”

I knew he was trying to cheer me up, but this was the wrong speech and Zelta’s worst fear.

“You’re angry,” he went on, dropping his voice again. “That’s understandable. Ah, I know what!”

He turned his back for the briefest moment, then opened his coat and thrust out his ample stomach. Zelta glided over to watch. She wasn’t used to his antics, but you could tell she suspected it was another of his gags.

“Go ahead,” he challenged me, raising his voice so the others heard. “Take your best shot.”

The room went quiet.

She was close enough I could say to her out of their earshot, “We used to do this a lot. He loves it.”

“You’ll feel better,” Milton said. “I promise.”

Even though I knew he had an iron gut, and even though I always pulled my punches when we clowned around like this, I hesitated. Something in the glint in his eye made me wonder how this time would be different. He was like that, sly but telltale. He had more fun when you were at least partly in on the joke.

Zelta shot me a look. “If you don’t, I will.”

You know, there are regrets in life, things you wish you could take back. This one took the prize.

I hauled off and slammed my fist into his stomach. Not all that hard, mind you. But hard enough, maybe harder than I intended to.

There was, as you’d expect, a collective gasp, and all eyes were on Milt.

Unfazed, he smiled broadly. Too broadly.

And then, at the corner of his mouth, there was a trickle of blood.

And then a gush, all over his white dress shirt.

Everyone was horrified as he stumbled back, fell onto the couch, and slumped over, as if he’d expired.

Zelta looked over at me in panic. Terrified, I looked over at my Mom.

Mildly annoyed, Mom looked down a Milt. “That’s enough, dear,” she soothed.

After a dramatic beat, he came back to life. He sat up and spit out a sticky-red cellophane packet, which he waved in my direction.

“Gotcha, young man!” he wheezed. “A new vegetable-based printer’s ink. Ran into the inventor over a friendly Scotch and got the world distribution rights.”

To everyone’s amazement, he got up, walked back over to me, and gave me an affectionate slap on the back.

“I tried catsup,” he explained, “but it wasn’t realistic.”

Zelta looked over at Monty, whose own worst suspicions were nowhere near bad enough.

2

We had our blissful night in Malibu, but of course it wasn’t all that much of a honeymoon. I thought Milt might have staked us for an exotic trip, but instead they invited us to visit them in Chicago. It was hardly a resort vacation, but we figured it would be nice enough as long as we didn’t stay too long.

Another incorrect assumption.

We’d graduated in June of 1944 and been married soon after, but we didn’t take Milt up on his offer right away. I had this idea I’d grab an aerospace job in California, and then Zelta wanted us the spend the holidays with her family out West. My job search wasn’t successful (perhaps my expectations were too high), and even though Milt probably would have paid our way, we didn’t want to be traveling back and forth across the country. So, between one thing and another, we didn’t make it to Chicago until the spring of 1945.

And, like I said, we didn’t plan to stay. Or, that’s what we told each other. In truth, we’d stayed away because she didn’t want to see him and I didn’t want to face him. Our going back was a tacit admission that maybe we were running out of options.

Milt and Edna had an apartment on South Lakeshore Drive, on the edge of Hyde Park. It looked out over the water, and it was, in pretty much all respects, the high life.

As we rode up in the elevator with our one suitcase, I wanted to tell her what it was like growing up there. Just me and our housekeeper Henrietta, when they were off on their round-the-world trips. He liked to fly, which so few civilians could afford to do back then, and of course there was always a business reason. He supposedly had a lot of friends in a lot of places. But he wasn’t exactly a captain of industry, at least, not outside of his own mind. Summers, they’d send me to Scout camp. I earned every merit badge there was. Twice.

She didn’t understand why I didn’t call him Dad, and I really couldn’t explain. He was Milton Reynolds the legend, smooth-talking Milt who’d already made and lost several fortunes, most recently on the loss side but absolutely sure he would find the next big thing any day.

We stood outside their apartment door. I smoothed down my cowlick and she checked her lipstick.

She gave me one of her sterner looks. “We are staying for a few days only,” she informed me. “If he asks you to work for him, say you’ve got an offer from Standard Oil.”

“I need a job,” I said, as if she didn’t know. “We can’t live on love.” And I tried to smile.

The door opened, and there stood Milt, grinning his face off.

“You two look great,” he said. Then, for my benefit, he exuded, “If New York is a glass slipper, Chicago is a work boot. Yessir, a man can make a deal in this town.”

He knew why I’d come.

I was about to say something in reply, but he fawned over Zelta as he ushered us in.

“And Zel-ta! I’d almost forgotten how ravishing you are.” He winked at me, actually winked. “You’re a lucky boy, Jim.”

“Man,” Zelta shot back. “He’s a lucky man. And whatever it is you’re selling, we’re not buying.”

Hoo boy!

Milt was speechless for once, and we walked past him into the apartment.

Henrietta was holding the door, and we exchanged smiles. There’s no mother like your mother, but Henrietta knew how to bake cookies. Before I could say anything, she’d taken the bag from my hand and stepped back as Mom rushed at us with outstretched arms. She was wearing one of those prim cotton frocks of hers, a new one that had probably come from the most exclusive boutique on Michigan Avenue. “Our son the engineer and his brilliant, beautiful wife!” she exclaimed as she kissed Zelta on the cheek and hugged me.

Milt was out ahead of us, gesturing expansively. Indicating the suitcase, he announced, “Henrietta will take that to the guest room. Your room.” She was turning away when Zelta grabbed the handle and wouldn’t let go.

“We’re not staying,” she said, and I somehow I thought we would be headed right back out. She realized she didn’t mean it quite that way and said, “Not long, I mean,” but she kept hold of the handle.

Then it was Milt who reached for the case. Bewildered, Henrietta let go, and he and Zelta had it between them. “Nonsense,” Milt said as he stared her down while he flashed his big grin. “You’ll stay until you find your own place.” Then, turning his expectant gaze to me, he announced, “Tomorrow, Jim and I are playing a call on the Goldblatt brothers.”

Zelta’s tightened her grip and looked over at me, as if waiting for my speech of defiance, which, of course, never came.

“What are we selling?” I ventured to ask.

“These guys run a multimillion-dollar operation,” he said, almost but not quite forgetting to hold his own in the tug of war. “We’ll have lunch in their private dining room, cigars, a spirited negotiation among gentlemen…”

Zelta could tell from my expression I wasn’t about to contradict him. She let go of the case, and Milt passed it back to Henrietta, who dutifully left to carry it into the guest room.