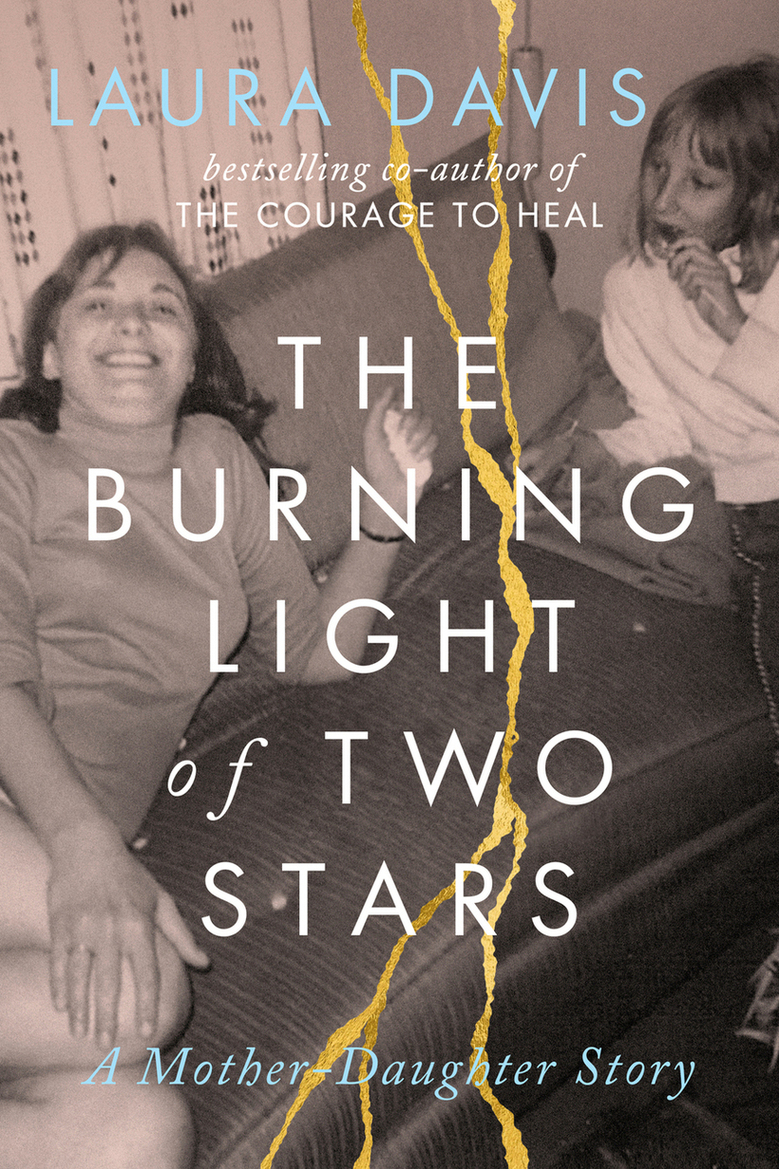

The Burning Light of Two Stars

SPARK

Summer 1956 Long Branch, New Jersey

I started life in a glass box. I lay alone, barely breathing. Eyelids thin, light stabbing. Body on fire, nerves raw. Beeps piercing my tiny ears. I couldn’t swallow. I couldn’t suck. Tubes down my nose, wires on my skin.

Where was she—the heartbeat that had answered my own? That soft, slippery chest pressed to mine?

For seven months, I’d held my twin in my arms. Even when we had no arms, I held her. She was always smaller, even when we were just a thought, a zygote, an embryo. She grew beside me, quarter ounce by quarter ounce, her pulse the echo of my own.

Weeks went by. Then months. She, floating in the safety of my embrace. Until the walls of our watery home began to squeeze.

Our mother was twenty-eight years old. She’d already had two late-term miscarriages. Now she thought she was losing another baby. She had no idea that we were two.

Moments after my birth, a nurse placed me on the scale: two pounds, twelve ounces. A scrawny chicken. As they rushed me to the neonatal intensive care unit, the doctor said, “Hold on, Mrs. Davis; there’s another one coming!” That’s how she learned about my sister.

Bone of my bone. Flesh of my flesh. The two of us identical. My twin lived twenty-four hours. I never held her again.

The rabbi advised, “Don’t build a monument to someone who never existed,” so my secret sister never had a memorial, a funeral, or a grave. But Mom insisted on giving her a name.

Vicki.

For six weeks after my birth, no one was allowed to hold me. And I touched no one. Doctors didn’t believe in holding preemies in 1956. I spent the next six weeks in a hard glass box—an Isolette, the perfect name for my healing prison. It isolated me from the broad expanse of my father’s chest, my brother Paul’s laughter, my mother’s eager arms.

Nurses wearing rubber gloves reached in to adjust my tubes, check my wires, change my tiny diaper. The whoosh of machines, the tick- tock of the clock, a pale shadow of the heartbeat that had sustained me, the one that I had sustained. The nurses took notes on hard brown clipboards and moved on to the next tiny baby. They did what they could and left me alone.

Babies my size weren’t supposed to survive. If I made it, the doctor said, I’d probably be blind or “retarded.”

If I made it, I’d be strong. A survivor.

My whole life rolled out from that beginning. When I think back now, here’s how I imagine it:

A newborn, tiny, weak, and in pain. My twin had died, and I could have followed her. Perhaps part of me wanted to just let go and disappear. But then I felt her—Temme Davis, the woman standing outside my clear glass box. Pulling me to her. Willing me to live. My baby, oh my baby, let me hold you in my arms. Beaming her life force through those hard walls. Stay with me, darling. Please be my baby. She pulled me into her blazing broken heart and claimed me as her daughter. Stay with me, she said. Whatever you do, don’t ever leave.

And so, I said yes to life. Yes, to my mother.

I had no idea just how much of a challenge that was going to be.

CHAPTER 1 RITUAL

Fifty-One Years Later Santa Cruz, California

I waited until I knew I’d be home alone. Karyn and the kids wouldn’t be back for several hours. This ceremony was just for me.

I pulled the giant white binder out from under the bed and carried it to the backyard, along with newspaper, an armful of kindling, and a box of Strike Anywhere matches.

The firepit in our backyard had been the center of many family celebrations. Today it would mark a different sort of occasion.

Sitting on the stone bench, I crumpled pages of the Santa Cruz Sentinel into loose balls and tossed them into the pit. Topped the paper with a pyramid of thin, dry pine with plenty of airspace in between.

Lit my pyre with a matchstick and watched the flames take hold. It was early June 2008. I’d waited a long time for this day.

The binder had been handed to me the summer before at the Stanford Cancer Center after I walked in, leaning on Karyn, for our meeting with the tumor board. As we pushed our way through the front door, we encountered an incongruous, yet comforting sound—a young man playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata on a giant black Yamaha grand piano.

As we waited to be called, I pressed my shoulder against Karyn’s shoulder, savoring the steadiness of her presence. But I couldn’t look her in the eye. When I was scared, I always reverted to coping alone. So, we sat, side by side, in separate bubbles. At any moment, the doc- tors were going to inform us whether I’d live to see our children grow up. Lizzy was ten; Eli, fourteen. Just let me see them graduate from high school. That was my mantra.

In neatly divided sections, the stiff binder had laid out all the information I needed as a breast cancer patient. Now, I opened the hard plastic cover for the last time. I clicked the rings apart, crushed the first page, and tossed it onto the fire. As the carefully tallied list of medications disappeared into the flames, something tight in my chest gave way. I threw in another page. And another. I leaned in. It felt good.

I thought back to the day I’d learned that life can change, just like that.

It was supposed to be a routine annual exam. Twenty minutes max. Then back to my busy life: writing teacher, breadwinner, mother, spouse. As my doctor palpated my right breast, we chatted about our children—they’d been classmates at Orchard School, a tiny rural elementary school where kids ride unicycles to class. We were reminiscing about the potbellied pig when she felt it. Something hard. She went back and felt it again. And then again. “I’m so sorry, Laura, but you’re going to need a biopsy.”

I didn’t hear anything she said after that. Just the word she hadn’t spoken.

I wadded up the next page—contact names and numbers—and threw it onto the fire. The stiff place in my chest loosened a little more. I threw in another page. And then another. The red and yellow flames devoured them all.

It had been a year of waiting. For my diagnosis. For surgery—just get it out now. For the wound to heal. The pain pills to work. For my head-shaving ceremony. For nurses in lead-lined smocks to drip poison into my veins. For the nausea to end. For food not to taste like rusty nails.

I fed a dozen more pages into the fire. They sparked into the sky, and the flames drove me back. I welcomed the surge of heat.

The day my oncologist told me I was cancer-free, I floated out of her office into a warm spring afternoon. I imagined Lizzy, racing after school to climb her favorite tree. I pictured Eli, his long fingers folding origami paper into impossible shapes. I’d be here to guide them. To launch them. To see who they would become. I thought about Karyn and the life stretching out before us. The students I might teach. The things I might write. Maybe I had another book in me.

Cancer-free.

I tossed the last page onto the fire. The empty white binder gaped open. Where did that leave me?

Gaining back the forty pounds I’d lost, waiting to feel like myself again. Whatever that meant. I had no idea.

So, I resumed my life: carpool, shopping, laundry. My cancer blog was winding down, and my writing workshops were picking up. But underneath, nothing felt the same. How could I possibly go back to the old Laura—the doer, the manifester, the woman who added tasks she had already completed to The List of Things to Do, just for the pleasure of crossing them off?

Who am I now? That question haunted my nights and thrummed beneath the surface of my days. But no one in my family wanted to talk about cancer anymore, or the questions that survived it.

I poked at the remnants of the fire. Orange and red embers, radiating steady heat. I held my hands over the glowing coals, took a deep breath, and spoke the words aloud: “I am not a cancer patient anymore. I am open to receive whatever is next.”

A deep quiet came over me when I said those words.

I watched the embers slowly fade.

It was time to discover who the new Laura might be. Maybe I’d be more present. Less driven. Less controlling. I hoped so.

I looked forward to quiet months with my family. No bombshells. No lumps. No toxic drugs. No surprises. Just a stable, steady life, so I could recover.

CHAPTER 2 THE CALL

Two hours after my ceremony, I tasted my homemade tomato sauce, simmering on the stove, added basil and oregano, a generous pinch of salt. A splash of red wine. Karyn was picking up the kids on her way home from teaching reading at Watsonville High. They’d be home in half an hour.

I was about to drop a handful of spaghetti into a pot of boiling water when the phone rang. It was my mother in New Jersey. We were due for a call; we hadn’t spoken in several weeks.

Cradling the phone between my neck and shoulder, I dropped the pasta into the pot, stirred to separate the strands. My glasses fogged with steam. I imagined her, smoking Parliaments, curled up with an afghan on the couch in the den. She’d probably just gotten home from her poetry class or her Shakespeare class or her Course in Miracles study group. I could never track her schedule. I set the timer for thirteen minutes.

“Laurie, I’ve got a surprise for you.”

“Oh yeah?” I was only half listening, maybe a quarter. I opened the fridge, rooted around for salad fixings.

“Why don’t you guess?”

“I dunno, Mom. What’s the surprise?”

“Don’t you want to guess?” I pictured her lighting another cigarette, residue of the day’s lipstick reddening the tip.

“Uh . . . you went to an audition and got a part in a play?” “No, I’m afraid my acting days are over. Guess again.” “Just tell me, Mom.”

“Are you sure you want to know?”

“Of course, I want to know.”

“Darling, I’ve finally made up my mind.” She paused for effect. “I’m moving to Santa Cruz. I wanted you to be the first to know.”

Blood rushed from my head. I closed the refrigerator. Leaned back against the door. Pictures of the kids and little square art magnets clattered to the floor.

It’s true—years earlier, in a moment of generosity, I had invited Mom to move out to California “when she got old.” We’d talked about it once or twice, but I never thought she’d actually take me up on it. It had been ten years.

“It finally feels like the right time, Laurie. New Jersey just isn’t the same anymore.”

That’s right. Your friends are dying off, going into assisted living, or moving to be close to their children. Oh my God. That’s me. My hand tightened on the phone.

My mother and I had been estranged for years. Yes, we’d forged a shaky peace, but three thousand miles still separated us for a reason. Our reconciliation went only so far.

“I love Santa Cruz. And I love your family.”

“Wow, Mom. That’s amazing. I mean...great...I’m so...happy.”

“Well, that’s good, darling, because I met with the real estate agent today. I’ve put my condo on the market. She says it’s the perfect time to sell a place at the shore.”

I collapsed onto one of the red cushy chairs at our yellow Formica kitchen table, stared at the black-and-white-checkered linoleum. The floor needed a washing.

“Laurie, are you there?”

“Yeah, Mom. I’m here.”

“You still want me, don’t you?”

“Of course, I want you. We all want you. It’s just that I never thought you’d actually do it.”

“Well, I’m not getting any younger.”

No, she wasn’t. Mom was eighty years old, and her memory was failing.

“You don’t sound very excited.”

“I am excited. I’m just surprised, that’s all.” How could I possibly be excited? The woman who’d betrayed me at the worst moment of my life was moving to my town. And I was the one who’d invited her.

A beep reverberated in my head and wouldn’t stop. Mom was talking about escrow and how hard it was going to be to pack. But I barely heard her. She was the white noise in the background. I was hovering outside my body, listening to just one voice—the one screaming in my head and taking up every inch of bandwidth: I’ve finally gotten through cancer, and now this? Why the hell didn’t you ask me? How about, Laurie, do you remember that conversation we had ten years ago? I’ve been thinking about it more seriously and wonder if you still think it would be a good idea. For you? For me? For us? For Karyn and the kids? Or how about, Laurie, I know you’re just getting over cancer. Is this a good time for me to move across the country to live in your town?

“. . . my friends told me about this gorgeous mobile home park right at the beach in Santa Cruz. De Anza. Have you heard of it?”

“Yes, Mom.”

“I’ll go right from one ocean to the other. So, you’ll stop by and talk to the manager?”

“Sure, happy to do that for you.”

I grabbed a brand-new yellow legal pad. It had been months since I’d made a list. What would I have put on it? “Take toxic drugs. Throw up. Smoke pot so you can eat. Grow white blood cells. Watch West Wing reruns. Survive.”

As I wrote “Find Mom a Place to Live: De Anza?” on the pristine yellow page, Mom said, “Gotta run, darling. I promised your aunt Ruth a call tonight.”

Click.

She hung up on me.

The timer was still beeping. I looked into the pot. The spaghetti had congealed into a gelatinous mush. I dumped it in the compost and set a fresh pot of water to boil. As I lifted the heavy pot, I knocked my favorite glass off the counter, and it shattered on the floor.

The kids were going to walk in at any moment, and they’d be starving.

I swept up the shards and set the table for four, but I couldn’t remember which side the fork was supposed to go on.

CHAPTER 3 FAME

Nineteen Years Earlier Laura 32, Temme 61, Indianapolis

Here’s how it felt to be famous. Riding to the auditorium in the back of a black Lincoln Town Car. Periwinkle leather pants on smooth leather seats. Periwinkle leather jacket. Fake pearls. Black patent leather flats. My streaked mullet spiked and gelled in place. Just enough makeup for my face to show under the lights.

Women lined up around the block, waiting to hear me speak.

A year earlier, in 1988, my coauthor, Ellen Bass, and I had published The Courage to Heal: For Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse, a six-hundred-page tome that guided women through the process of healing. From coping to survival to thriving, our book provided a road map. The first. The Courage to Healgalvanized a movement.

There were so many requests for us to speak that Ellen was lecturing on one side of the country while I flew off to the other.

Soon I’d be out onstage, every seat full, hundreds of faces turned toward me, drinking in my every word. The thread of excitement winding up my spine competed with the memory of vitriol from my mother’s call the night before: “You and your hate book. Traipsing around

the country, spreading lies about our family on national TV. You published that book just to destroy me!”

As my driver pulled up in back, a line of women snaked around the corner, standing in small clusters, holding copies of The Courage to Heal, waiting for the doors to open. As I slid out of the car, I could still feel the heat of Mom’s rage: “You and all the other lesbians. Ninety percent of you say you’ve been molested. You all hate men. You hate your mothers. It’s the ‘in’ thing. Your badge of honor. Who had it worse as a kid!” Then she hung up on me. The finality of her slam still reverberated as my host rushed up to greet me.

“Let me take you right to the green room, Laura. It’s going to be a full house tonight.”

I pushed the memory of my mother’s voice away. I was not carrying her with me into that auditorium. Some of these women had driven hundreds of miles to hear me speak. My job was to inspire them, to let them know they weren’t alone, that healing was possible. I was determined to deliver. I buried Mom’s words behind a steel wall inside me.

As someone introduced me, I waited backstage, doing the vocal exercises I’d learned in seventh-grade speech class: rehearsing my first lines with my tongue fully extended—opening my palate, opening my voice.

To prepare myself for the intensity ahead, I imagined my feet rooting down into the molten center of the earth, pulling heat back through my body until it glowed inside me. As I waited in the wings, sweat dotted my spine, and I grew larger. My whole body tingled. Clip a…