30th January 2018

A still sunrise is soon to break over the village of Brill in Buckinghamshire, on a blue day sharpened by diamond frost. Largely red brick, Brill sits high on a round hill along the upward English curve which divides stone houses from brick, the placid Cotswolds on the west separating away from the hardworking Midlands to the east.

Brill has a history of keeping mum.

I went to Noke

And nobody spoke.

I went to Brill

They were silent still.

The sun will take longer to light up this west-facing bedroom window of our Airbnb house overlooking the village green. A brave shrub of winter flowering honeysuckle sits by the front door and its fragrance whispers in through the window, lifting winter’s chill. A blackbird, Gregory Porter of garden birds, is fluting out his heart on the pear tree outside, although spring is weeks away. Perhaps it’s a serenade for Mum.

Nestled next to the man I am due to marry this summer, a second chance for each of us, feelings of peace – and, in truth, relief – are unfurling after the drama of my mother’s death before Christmas. While Tim sleeps, I twist a ring around on the little finger of my right hand, before lifting my hand out from under the duvet to look at it as the sun leans into the day. The ring holds a small, milky, oval opal in a raised gold frame. Its gold band is adjustable to fit any finger. Familiar, unfathomable, flashing pink, blue, turquoise depending on how the light falls, the opal flickers red when it touches skin. I have known my mother’s ring for as long as I can remember. No one ever told me who gave it to her: most likely it was my father.

Today is Mum’s funeral. My sun-worshipping mother died on the shortest winter day, when the sun has its least power. ‘She wouldn’t have felt a thing,’ the coroner advised me. ‘It would be like a light being switched off.’ Her heart gave out unexpectedly, eight days after her admission into care, her much-loved freedom docked. This begins a time when I hope I can also lay to rest the ghost of the ‘accident’ of my brother David’s death, and speak more openly about how his life ended.

You are only as sick as your secrets, so they say. I have been trying to heal myself from the secrets of my past for a long time now. But my mum’s confession about being ‘afflicted’ (sadly, her choice of word) which she handwrote on the back of a white envelope, left to be found by me after her death, means I will carry another secret for a while longer. This one none of us even suspected, whereas everyone really knew what had happened to David.

I don’t want her funeral to be about the envelope. I want her day to be about the life she decided to lead with my father for the nearly fifty-nine years they were married until the day he died; about her being a doting grandmother; about the grand houses they lived in, their travel, setting up the Doncaster Film Club, the theatre, parties and conviviality they loved. The things she was proud of, including being a mother. I owe her that.

My mother said it was important to get things right. Black for funerals. I’ll be draped in midnight from my platform suede shoes to a glossy feathered hat, with a veil part covering my face – she would approve of the veil. Apart from my lips, which I’ll paint red to celebrate life, the only colour on me will be her opal ring.

I silently practise the first line of the eulogy I plan to give later this morning.

‘I am and will always not be the same but be different.’

This is how she began her handwritten confession. I won’t read any more from it at the funeral; the time for that will be later.

In the meantime, how can I begin to unravel the truths hidden within my family of origin; shrouded by secrets for so long? I’m aware that I simply do not know how much I don’t know, but then maybe that’s true for everyone. In childhood, normal is whatever normally happens.

We could start with the day that changed everything, which still cuts deep. Nobody could say that what happened on that day was anything like normal.

My younger daughter, with clear-eyed teenage wisdom, once said, ‘Stuff happens, Mum.’ Stuff. Who could argue with that? When we’re young we know so much. Then we have to forget when we’re grown up, in order to get by.

I won’t pretend that the stuff covered in this book is easy reading. If you choose to turn away, you wouldn’t be the first. People have crossed the road to avoid speaking to me in the past. I can’t blame them.

If you are carrying on reading, you might like to figure out why this stuff did happen. I won’t be able to give you all the answers; there are things that I don’t know even now. My family begat more questions than answers. I would hazard a guess that you’ll identify more of the causes than I have, even though I’ve spent nearly forty years puzzling it out.

I am writing this book now to keep a promise I made to myself back in 1981. The most important promises are those you make inside. If you can’t trust yourself, how can you trust anyone else?

For those brave enough to read on: thank you. I will use my best endeavours to explain what happened. That’s a term in law, by the way, ‘best endeavours’. I could instead say ‘undertake’, which is a higher legal test. But I don’t honestly know what was going on inside others, only myself. And I’m not even certain that is accurate. I’ll stick with best endeavours.

I don’t want to make a promise I might break. There’s been enough of that already.

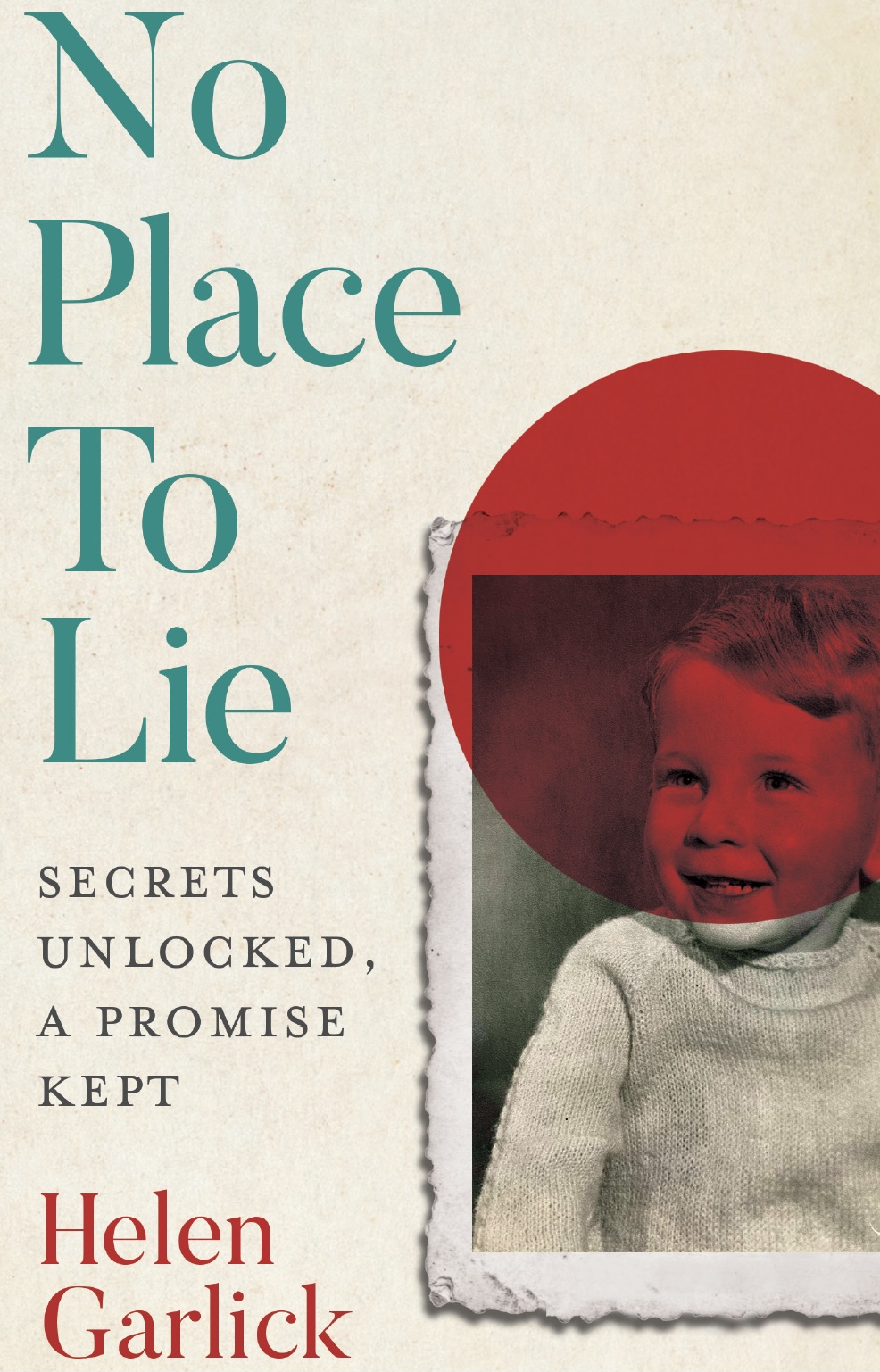

Part One A Beginning

Live as long as you may, the first twenty years are the longest half of your life.

Robert Southey

Foxes have holes, and birds have nests,

but the son of man has no place to lie down and rest.

Luke 9:58

Chapter 1

If anyone had asked me about my family then, I would have said there were four of us, although that would no longer be the truth. We could have been five, but my little sister died before she took a breath. Today, which happens to be a Sunday, we are down to three.

If you could see through a gap in the closed curtains of the green room of Bothamsall Hall, Nottinghamshire, you might detect a black bakelite telephone on the floor next to the settee, receiver askew from the cradle. Near the phone, also on the floor, is a lamp knocked over, its shade broken away from the base. Next to the settee lies my younger brother David, not quite twenty-one years old, on the black and red carpet, his unseeing eyes still wide open. The Russian shotgun, containing one spent cartridge, is shielded from sight by his body. It is held in David’s left hand, pointing towards what was his temple. Fragments of my little brother trace an arc from his head upwards to the wall and ceiling in the room where he took his last breath the day before. Or it could have been the day before that, or even earlier.

The overhead lights and the television are on and have not been switched off for several days. No one has been bothered enough by this to check what’s going on. Nobody has knocked at the door in the last week to see if he is all right. This is about to change.

1st March 1981: St David’s Day

My father Geoffrey swings his automatic burgundy Daimler through the gate pillars, ignoring the ‘Private’ sign, and over the driveway of Bothamsall Hall, to pull up by a yellow Renault 5 hatchback where the car purrs to a stop. He places the gear lever in park, slips on the hand brake, and looks at his watch: 4 p.m. The drive up from London has been long. Quickly checking his reflection in the mirror, he threads a greying strand of hair across his balding head, while thinking about his son. He allows himself a momentary hope that this time things will be easy between them.

After the dusting of snow a few days ago, it is unseasonably mild. A drizzle mists over the scene as grey light fades into dusk. He is reluctant to step into the cold outside, but he has his duty to do. He looks across at his wife, sitting in the passenger seat beside him.

‘I’ll pop in to see if David’s tidied things up before you come in,’ Geoffrey says. ‘Look – the lights are on inside, and I think I can hear the telly. It’s a blasted nuisance the phone’s not working. Fault on the line, the operator said, if you believe that. You stay here, Monica, in the warm. I won’t be long.’

My parents have just come back from a holiday in Cyprus, to get away from this English winter, top up the tans. It’s the first holiday abroad they’ve had this year and it won’t be the last. Rolling stones, Geoffrey and Monica, that’s what people say. Always going from this place to that, one home to another. He likes it that way; it makes life interesting.

She doesn’t answer, but nods and turns away from him to look at the garden, still awash with leaves from autumn, drifting in clumps under the trees and hedges where the wind has blown them. That needs clearing up, she thinks. She wants to get out of the car and see her son David, her younger child, as soon as she can. She’s missed him on holiday. But she’s not overly fond of Cleo, the Gordon setter he’s looking after for her daughter – or any dog, come to that. So she obeys and perches herself back in her seat. She exhales extra heavily to tell Geoffrey that he is making her do this.

Her husband pushes himself out of the car, slams the door harder than he meant to, and walks towards the house, past the yellow hatchback, brushing his hand on the bonnet. Stone cold. The shadows are darkening but in the boot he can still spot dog food – at least twenty tins of Chappie, as well as several yellow and red bags of Pedigree dog biscuits. That’s pretty odd. He checks the car doors, all locked, before walking around to the front of the Hall. No sign of his son here. He rings the front door-bell and hears its chimes echoing in the hall. Geoffrey has his own key to the front door but that’s in the safe in his Doncaster office. He tsks in irritation. After a pause he rings again, this time for longer. Still no answer. He turns on his heel to retrace his steps and walks around to the back door.

He finds it shut, but with a key fob made with a wooden cotton- reel bobbin, which he doesn’t recognise, hanging from the lock, the bobbin attached with coloured wool to the heavy metal key and waving slightly in a gust of air. He has to knock as the doorbell hasn’t worked for a few weeks now. David really should have fixed that. Apart from the sound of the TV, or maybe a radio, all he hears is silence. Not even a dog barking, or howling at the moon as Cleo is sometimes prone to do. And there is no response to his knocking.

He might be walking the dog, Geoffrey tells himself. Or maybe he’s on the loo. Holding his breath, he cranes to hear whether it’s a radio – no, definitely the telly. He tries the handle of the door, which opens before he even needs to twist round the key from which the bobbin dangles down. The door catches slightly on the floor beneath, so he has to thrust it harder before it opens enough to let him in. As he steps into the door, he sees a packed bag and a neat pile of David’s belongings, carefully ordered, in the hall, as if his son is ready to go.

‘David?’ he calls out. Still no answer. Taking a deep breath to make his shout louder, he feels a chill biting into his lungs. It seems colder inside than out. Why hasn’t he put the central heating on? Perhaps he wants to cut down on bills for the owner? Well he didn’t really need to do that, Geoffrey thinks. The owner is well off, I should know, he’s my client, and he’s lucky to have my son look after this pile whilst he’s away.

Geoffrey makes his way to the green room to check if his twenty-year-old son is asleep in there.

Outside in the car, Monica sets her navy blue leather handbag down on her lap, unzipping the pouch underneath the flap to take out her diary and her Sunkiss lipstick, placed just there, like always. She pulls down the sun visor to check her face before carefully painting the curved bow of her lips, first the bottom and then the top lip, smiling as she catches the glint of her opal ring on her right hand in the mirror. She squeezes and rubs her lips together to even the colour out, an elegant shade of peach, not at all common. Not baby pink, like her younger sister Judy might go for.

The shape of Monica’s lipstick is the exact moulded contour of her mouth. She can put on lipstick pretty much with her eyes closed, even without a mirror, and she sometimes does, at the table at the end of a dinner party before the dancing starts. She gives a faint smile to herself in the reflection of the mirror, looking at the freckles on her face from the Cypriot sun, her high cheekbones, cornflower blue eyes, before her face rests back into the stillness she normally wears.

She opens up her diary to make a note in biro, straining to see the page. 1st March. Check with Bill – Cleo? Dog food? Phone mother. Butchers Tues. 1lb of mince, 2-3 chicken legs? 1⁄2 doz. eggs.

Monica plans to have her son over for a meal at 13 Albion Place. She likes to see him as much as she can, preferably on Wednesdays, it breaks the week up a bit. Usually she and Geoffrey go to Bothamsall but it would be nice to cook for David at home this time. She could do his favourite, spaghetti Bolognese, with grated parmesan if she’s got some. He’ll have to bring that dog, I suppose, she sighs. But if Geoffrey says that we can’t have spaghetti Bolognese as it’s too messy, I’ll suggest we have chicken legs instead. Geoffrey doesn’t like legs, he only likes breasts, so that might mean he’d opt for Bolognese. Her lips move into a slight smile. That will work and Geoffrey will think it’s his idea.

She wakes up from her reverie: Geoffrey is tapping on the car window. ‘Monica, Monica.’

He says her name over and over. She winds the window down and sees her husband’s green eyes are wet, his pupils black holes. His face is ashen. She watches him for the seconds it takes him to find some words. Geoffrey always knows what to say. What on earth is wrong with him?

‘Don’t come out. Stay in the car,’ he stammers. ‘I don’t know what’s happened. There must have been an accident. Or there’s been an intruder. But you mustn’t come in. You can’t. We can’t touch anything or move anything although I’m going to have a look around. We’ll have to wait for the police. I’ve already called 999, and they’re heading straight over.’

Rebelliously, she moves to open the door handle, but her husband pushes the door back firmly, leaning against it with his whole weight. He clears his throat to speak more authoritatively, like he usually does.

‘No. Listen to me, Monica. Don’t come in. It could be the death of you. Don’t move. Stay right here, you promise me? Wait until I come back.’

Monica sinks back in her seat, suddenly sapped of strength. She nods her head again but this time again watches her husband like a hawk as he heads back inside the Hall, forcing her eyelids open, not blinking, to work out for herself what is going on. What has happened to her golden boy?

Chapter 2

This may or may not be the truth of what happened. I was not at Bothamsall Hall, together with what was left of my family. Although ‘together’ would be misleading: there were spaces between us, not connections. Silences were familiar territory; my homeland.

A version of the facts became the family story, as I recall it, of the agony of my father discovering my brother’s body, pieced together from my parents’ clues as well as my imagination. Sometimes my parents alluded to a bit of what had happened; occasionally they might have said ‘I said ...’, or ‘You said ...’, and told me something they may or may not have said. I’ve included in this book scenes in the voices of each of the four main characters, which you could say wouldn’t be the truth, but I’ve tried to be as true as I can, with my current 2020 vision, to the spirit of what happened.

I’ve usually had to figure things out on my own.