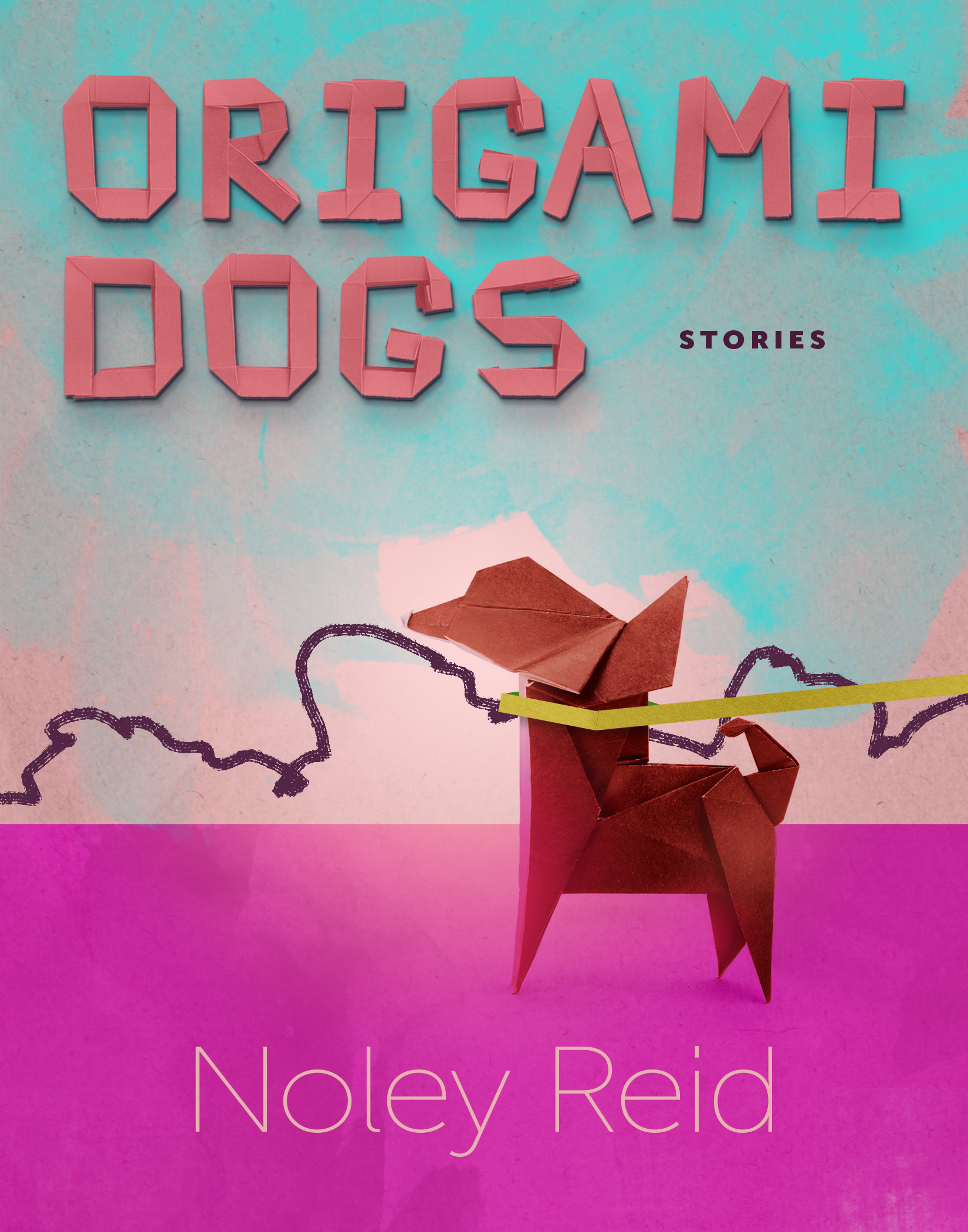

Origami Dogs

Stories

182 pages

51,204 words

by Noley Reid

10444 Devon Ct.

Newburgh, IN 47630

noleyreid@gmail.com

www.noleyreid.com

812-760-5655

Acknowledgments

These stories first appeared, sometimes in slightly different forms, in the following publications:

CRAFT Literary Journal, Peatsmoke Journal, Green Mountains Review, storySouth, Confrontation, Spoon Knife 5, and Moon City Review.

To the whisper-snout snufflers

whose hearts have taught me nearly everything I know,

Henrietta, Bugsy, Ruthie, Trumon, & Dodg’em

Table of Contents

Origami Dogs.………………………………………………………...5

Shepherd.………………………………………………………….....29

Movement & Bones……………………………………………….....50

How Trees Sleep…..…………………………………………….…...70

Once It’s Gone...……………………………………………………..74

Sick Days……..……………………………………………………...95

The Mud Pit……….………………………………………….……..122

The Suicides………………………………………………………...150

No Matter Her Leaving…………………………………………..…157

Origami Dogs

Iris Garr rose at four every day before school to feed and water the dogs in the barn. They weren’t hers. They would never be hers. She used to beg—how old had she been then? She didn’t remember it, just the feeling of the want so intense it was like a rock in her mouth—and then she had to stop or she thought maybe she would die from the sadness of it. The dogs were her mother’s and they were money. Right now, there were thirty-seven but sometimes there were only twenty and sometimes there were over fifty. Her mom, Gloria, drove all over Indiana or out to Kentucky or Ohio or sometimes Michigan with her tried-and-true dams to mate them with the best champion studs she could afford, to keep the breeding going and going and going.

The barn had individual pens for each breeding female—Iris could never call them bitches—arranged by breed. First came all of the small dogs: the miniature pinscher, Chihuahuas, Yorkies, Westie, and Maltese. Next were the medium dogs: the spaniels, bassets, whippet, and beagles. And then the large dogs: the English Setter, black Labs, the dalmatian. Her mom used kiddie pools inside the pens as whelping boxes and while the puppies were still small, the pools prevented them from escaping and ensured the mother dogs could nurse them all together. They were easier to clean, too.

This morning, Iris found no new litters. One of the beagles was going to start contractions any day now. Iris didn’t like leaving her. She lingered some at her pen, watching the dog. In the night, the beagle had made a nest out of the towels in the whelping pool but wasn’t pacing or panting yet. Iris checked on the Westie, only halfway through her pregnancy, then walked down to the large dogs, the heavily pregnant dalmatian whose flank rippled with movement, and the Lab litter. Roly-poly seven-week-old puppies that climbed on one another and their mother nonstop, grunting and snuffling. The pool didn’t contain them anymore. Iris reached a hand down into the pen and two or three immediately glommed on to her with their needly teeth hidden inside velveteen muzzles. “You poor thing,” she said to the mother dog, extricating her hand and rubbing the red marks.

Iris finished filling the water bowls and bottles and poured puppy kibble in all of the food dishes. She kneeled at one of the basset hound’s pens because the dog wouldn’t start eating alone. “Good girl,” said Iris, stroking her long back. Then Iris scooped poop and wet shavings from the pens and put down more bedding and fresh towels where they were needed. The Yorkies always peed all over their towels instead of the shavings and danced circles around Iris’s boots while she worked. “It’s alright,” she told this pen’s dog, “I know you can’t help it.” Gloria said pregnancy was tough on the bladder and the nerves. Iris reached down to move the Yorkie into her pool, but the dog popped right back out and was underfoot again, so Iris simply worked faster. She brushed the two spaniels’ ears and the English setter’s speckled ears. Her mom kept all the long-coated dogs clipped short but the long ear fur still matted if given the time. The setter licked Iris’s knee, the denim covering it, as she brushed. Now Iris shelved the brush and went down the length of the barn, giving each of the other dogs and puppies a pet on the head, behind the ear, or on the rump, depending on what was accessible, then she went back to the little, aluminum-sided house nestled in southern Indiana’s rolling hills.

Inside, she sat at the kitchen table with toast and orange juice. She wrote her mother a note:

The beagle’s about ready.

Please check on her today

before you leave for work.

By 6:30, Iris was on her bus to the high school. She smiled at the driver, who once whispered to her that a dryer sheet was sticking out of her pant leg. She sat in her regular middle seat. The popular and older kids sat in the back. They talked of love lives—real or imagined, Iris didn’t know. They talked of video games and TV shows Iris had never played or seen and knew she never would, homework and tests happening that morning, how Mr. Flynn was a dick to assign three chapters last night. They laughed and said things that made Iris smile and want to be part of them, and even for a moment she shut her eyes and imagined she was a junior or a senior and was with them.

“What stinks?” said one of the girls.

Iris opened her eyes.

Iris heard the tussling of bodies tumbling into one another and more laughing.

She looked down at her shoes, which was dumb since she’d worn her boots in the barn. She touched two fingers to the damp spot on her knee. She didn’t think she smelled of dog but she wasn’t sure. Carefully, she tucked her nose into her sweater and sniffed. Maybe she should have showered. Or changed her clothes after mucking out their pens. She couldn’t tell.

“What did you step in, Grady?” said a boy.

“Me! No way. Check all y’all’s feet.” Just an hour and a half across the Ohio River, but she could always tell who was originally from Kentucky.

At lunch, Iris sat by herself at a table of other kids sitting by themselves. She ate her burger then smoothed the foil wrapper and folded it into an origami Scottie dog.

“That’s cool,” said the boy diagonally across from her. His name was Denny McCauley. He was in her biology class, sat way at the back. He had short black hair and every day wore black shirts with a black zip-up hoodie, black jeans, and black Converse shoes. Today was no exception.

Iris smiled. She pushed it across the table to him.

“Thanks,” he said.

Iris took her tray and dumped it.

Fifth period was biology and Denny’s arm brushed hers when he walked past her to his lab table.

On the bus home, Iris thought of the beagle, hoping she hadn’t gone into labor yet. Once there, however, she found the dog shivering through contractions. Iris sat in the pine shavings of the pen, with the dog in its whelping-pool nest. She stroked the dog’s back. “That’s it,” said Iris. “That’s a good girl.”

The dogs didn’t have names. Gloria insisted. She referred to them by the number she gave them when she first acquired them but Iris couldn’t bear to think of the dogs as numbers. So they were all just good girls.

Now the barn was quiet around Iris and the beagle. It was always like this. Anytime a dog whelped, the rest of the dogs and puppies hushed. The beagle pushed and Iris took her hand away but said, “You’re doing such a good job.” After a while, there was a puppy. The beagle looked back at it then picked it up so gingerly and set it down before herself so gingerly and licked the membrane from the puppy so it could breathe and chewed the cord and placed the puppy at her side so it could nurse when it was ready. The beagle panted and shivered and began pushing again and thirty minutes later, she delivered the next pup. She carried on like this well into the evening’s first darkness.

“Iris?” It was her mom coming out of the house, back from her shift at the library, and flipping on the barn’s lights.

Iris blinked away the brightness. “Back here,” she called. “There are eight already.”

“Good job, 27!” Iris’s mom clapped her hands together silently and leaned on the gate of the pen. “How many more do you think there’ll be?”

“She might be done.” All but one of the pups was nursing. It squealed softly like a guinea pig, like the newborns always did. Iris picked up the straggler—all spots and big, round snout—and placed it at a nipple. It snuffled on.

“Have any homework?”

Iris nodded.

“Head inside. I heated you up a dinner to have while you work. I’ll stay with her.” She opened the gate and stepped in.

“Make sure this one gets milk,” Iris said, pointing.

“I will.”

“This one. With the white notched spot on the neck,” said Iris.

Gloria was touching each pup on the head, counting.

“I said there are eight. Just watch this one. It needs to nurse.” Iris stood up.

Gloria stopped and looked up at her daughter. She ran her tongue over her teeth. “I know what I’m doing,” she said.

Inside, Iris ate her tray of chicken tenders, mashed potatoes, and green beans while studying genetics and heredity in her biology text. She ran through a table of Mendel’s inherited traits, drew out Punnett Squares for brown eyes, free ear lobes, non-cleft chin, mid-digital hair, and left-on-top hand clasping, then wrote down her phenotypes and genotypes accordingly. It was the kind of stuff her mom did when breeding the dogs.

She was asleep when her mom finally came in.

“She finished with nine,” said Gloria, standing in the doorway of Iris’s room and rubbing her neck.

“Are you sure she’s through?” Iris sat up in bed. “I can go back out.”

“No, you sleep. She’s all done. I waited long enough to be sure.”

Iris lay down again but couldn’t fall back to sleep. Once, they lost a Jack Russell who labored too long. They’d thought she was done, too, and maybe she was. Gloria said she’d waited with her long enough to know the whelping was complete but the next morning when they checked on her, she was dead and so much blood had come out of her back end. They didn’t know what happened, but Gloria cleaned it up and put the dog’s four lifeless puppies in with a Maltese who’d just had two in a litter a few days earlier. The four were already gone, though, no matter how much the Maltese nervously licked their wet coats to get them breathing.

Now Iris listened to her mother brushing her teeth, running a shower, flushing the toilet, and climbing into bed. And then Iris put on her boots and coat and went to the barn. She sat in her nightgown with the beagle and her sleeping puppies, just to be sure.

When birds began to warble, Iris shook blood back through her limbs and rushed through her chores. At school, when she opened her locker, something fell out into her hands. It was an

Comments

Great start!

Really well written, and it kept me on the edge of my seat waiting for a sad moment!

Thank you!

In reply to Great start! by Jennifer Rarden

Thanks so much, Jennifer. I so appreciate your reading Origami Dogs and this kind comment!!