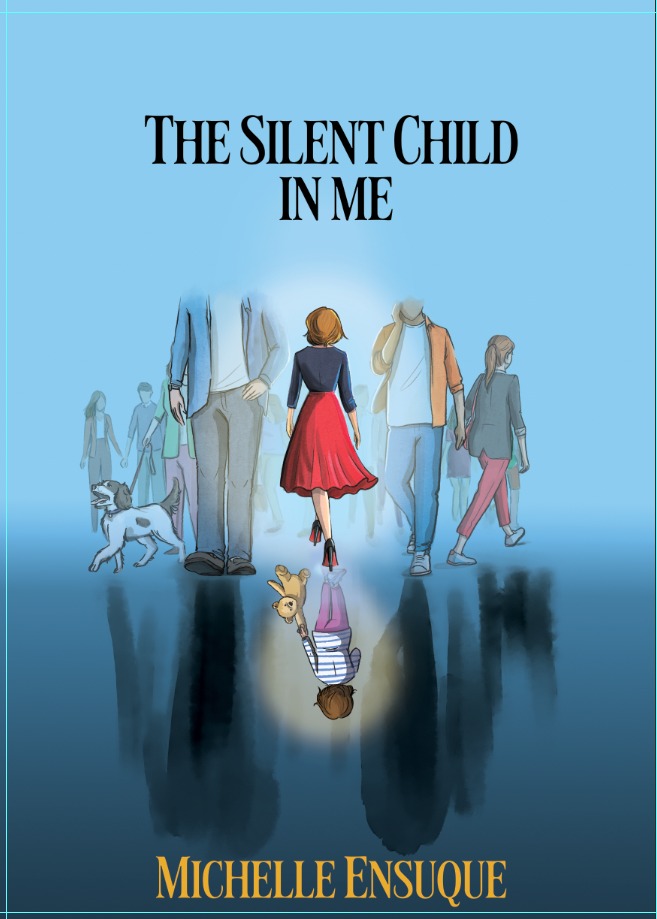

As I look back now at the silent child in me

I see frightened eyes and fear where joy should be.

I didn’t know it then, but fear would have the last laugh,

As later it pulled me down an ever-spiralling path.

There at the bottom I looked up at a wall of grey,

No sky at the top to welcome, no sense of light or day.

Was I in this life or the next, I wondered? It mattered not, I thought,

As my fingers scrabbled on the surface, as a way out of there was sought.

The climb was long and heavy and not without some pain,

But finally, I reached the top and gone was my shame.

The shame of imperfection, of not being good enough

Was replaced by something other, more resilient and tough.

To my silent child I say, you were stronger than you knew,

Your defiant stance and bravery were the very essence of you.

I love you, my silent child, for dealing with all that pain,

Tell your story to the world so others don’t endure the same.

Chapter 1: Grandad, I Love You

Oi, you! Yes, you! I can see you turning the page back to see if you’re in the right place. What? No prologue? No long introduction where I’m supposed to give thanks to my loved ones, my hairdresser, the dog groomer or my acupuncturist for giving me the inspiration or support in writing this? Nope, we are here, cutting to the chase, getting down to the real stuff from page one. If you’re like me, I barely read those prologues anyway. I just want to get to the story! So, with that out of the way, I’m Michelle. Nice to meet you. Are you ready to begin?

It was time to leave. Nothing weird about that. The holiday was over and it was time to go home. So I set about packing. I had a faint feeling of déjà vu but wasn’t quite sure why, and then realised the time. Dammit! The transport will leave soon! It was 4.20pm on my watch and the bus was leaving at 4.40pm, but there was so much to do. There were two huge suitcases, big black ones, soft and squishy. But packing everything required it all to be sorted if I was to fit everything in. But why was that the case if I hadn’t really bought anything? Ithought, why didn’t I sort all this last night? Still, methodically I went through the items, putting them in ‘to leave’ or ‘to take’ piles, until suddenly I noticed it was 4.50pm. No! Running downstairs, I yanked one of the suitcases with me; it bumped down each step, nearly pushing me over in the process. I was half-hoping I would still see my friends waiting. But no, of course not. Where they should have been were just empty chairs. Empty packets wafted in the breeze – packets that had once contained a hot dog bursting out of its doughy cushion, remnants of sauce still remaining on the paper, mustard and tomato colour. Why hadn’t they called me to see where I was? That struck me as not very kind. There was nothing and no one outside either; everything seemed eerily quiet, which in itself was odd because I was in Delhi, where nothing stood still or was quiet – at least, not for very long.

Suddenly my heart was pounding. I started to panic, but just as I did, I opened my eyes, shot bolt upright and realised that it was just a dream. The relief! Slumping back down into my pillows, I pondered the fact that it wasn’t the first time I had dreamed this scenario. The location might have been different, but it was the same story. I wondered what the oneirologists or Freud would say about that. Anyway, that day I decided to do something different. To return to the same place, but this time I wanted to change the ending of the dream to something far more positive. After all, if it was in my head, I could do that, couldn’t I? Settling down, I took myself back to the point just before I had woken up. I was in the bedroom. I threw everything into the suitcases, went downstairs, got on the transport and travelled to the airport. I was still alone, but this was much better than the other ending. There was an old couple in front of me in the queue, and although I could feel the dream trying to introduce things like ‘Is this the right airport, or the right queue?’ I batted them away like flies and maintained my focus. Now I felt much safer, much surer of the direction of travel and, more importantly, in control. While I didn’t see myself arriving home, I felt safe enough to open my eyes and return to the real world, knowing the one I’d left behind was just fine. If only life could be like that, where you could rewind and create a more positive outcome, I thought. Well, later in life I would be able to do just that, but at this point there was only one ending, and it wasn’t a good one. There are some things, after all, that you can’t change.

The rain was pouring down the glass. The inside of the coach window was steamy. The air was damp and heavy, full of people’s warm bodies and wet clothes from standing outside in the rain. There was lots of excited chatter as people discussed where they were going. I sat there in my little red coat and hat as we waited to depart for the trip. Swinging my legs back and forth, I took a sneaky peak sideways at the man sat next to me. He had a pointy nose and his chin poked out. It was a strong look, but I never got tired of it. “I never want you to die, Grandad.” “Don’t you?” he smiled. And with that he was gone. One minute we were on the bus, off on a day trip together, and the next he had disappeared from my life. I was nine. How was that actually possible, I thought. Had he been abducted by aliens? I had heard about such things and it seemed entirely possible; I mean, I didn’t know anyone else who had just disappeared into thin air. People talked about it, but it just seemed silly. There was something else ‘off’, though. A bit like a bad smell that you didn’t know where it was coming from but you kept searching for it because you knew the answer was somewhere. This was like that. There were also people toing and froing from our house. I giggled. This shouldn’t be unusual, but in this house no one really visited, apart from those who lived in it (and I’m not sure even they wanted to be there) and a few family members. My other grandad cycled round sometimes on Sundays and said he was off to the church where they had handles on the prayer books. For years I hadn’t understood it, especially as he had never uttered anything religious in his life, until one day the realisation of where he was actually going lined up like fruit on a slot machine. Anyway, the comings and goings made me thoughtful. There must be something going on. Obviously I was just a kid; there was no need for me to know. Out of sight, out of mind.

There was a vague memory of being told Grandad had died – a heart attack, apparently – but it was one of those memories I couldn’t quite touch. Don’t give me that twaddle about it being so far in the past. A smell or song could ricochet me back into an old memory in a nanosecond. No, this was the realisation that this was such a bad memory the brain had decided to store it so deep that no one could find it. That way, if you can’t find it, it can’t hurt, right?

On the day of the funeral, I went to school like any other day. My parents must have told the school what had happened, as rather unusually I found myself sitting on my teacher’s knee. He was talking away, probably about how death was natural and a process for old people, but really it was like his lips were moving but there was no sound. I looked round at everyone else in the room. Did I really know any of these kids? Even now I can’t picture a single one of them. Did they actually care about what I was thinking or feeling? Right now, who was actually with me? No one. As per normal. As an only child, life pretty much existed in my own head. Not in an invisible friend kind of way, but in a ‘this is enough’ kind of way. Anyway, I sat on his lap for what felt like ages, but all I felt was the scratchiness of his trousers on my legs and all I could see were his glasses wobbling on his face as he talked. I wanted to giggle, but that seemed inappropriate. I struggled to remember his name. Was it Mr Waring? He was my favourite teacher, always praising me, telling me he loved my story writing, and I was so proud I thought my heart might burst. Compliments were few and far between, so I took what I got.

So he might have been talking about my grandad but, honestly, it might as well have been about the weather. I wondered if I ought to be at school at all, and thought vaguely that maybe I should be somewhere else. Later I understood that my parents considered I was too young to go to the funeral; but I was nine, not dumb. I knew that I had needed to see it for myself in order to accept it. The suddenness of it (it wasn’t the last time I would experience someone’s sudden death) and not seeing his coffin left an imprint of disbelief, of thinking that he actually hadn’t died. That it was all a lie and any time now I would see him walk up our driveway, or that he would meet me outside school on Wednesdays, just like he used to. For years afterwards I saw his face in a crowd, and every time I did it made me catch my breath – my heart fluttered and my stomach somersaulted with joy, and then seconds later it plummeted when I realised it wasn’t him after all. It was like those first few seconds when you wake up, having forgotten a tragic event, thinking it was all a dream, before, two seconds later, reality kicks in. There was no changing this dream, though. I hadn’t just lost my grandad; I had lost my safe place.

Closing my eyes, I could warp myself back to his house in a split second – the place where, from about six to nine years of age, I felt most loved; where there was calmness, peace and tranquillity and an open fire. For hours I used to love watching that fire, the open flames flickering. There was no TV, but that was OK. There was the fire, happiness and love in abundance. Not the sicky-icky kind that comes gushing out every five minutes, but just a ‘knowing’ that love existed. In this house, unlike the one I shared with my parents, there was no shouting, no awkward painful silences and, most importantly, no fear. I felt relaxed, and every time I walked over the threshold I let out a huge breath and felt my shoulders relax and the knot in my tummy release.

The journey to his house for those week-long holidays was hilarious. He had this immaculate Ford Anglia. Was it grey or lilac? Not sure, but it was pristine. He absolutely refused to drive more than 40mph and I used to silently giggle at the queue behind as he drove onwards, oblivious. They are strange, aren’t they – memories? There are the ones I pushed away, because remembering them caused too much pain, and yet there were others I could recall as though I had experienced them the day before. Such as running upstairs to get a book from the bookcase that was on top of the landing: Enid Blyton, the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, Agatha Christie, Inspector Poirot. My favourite place in the whole house was his armchair – still much loved and now decadently covered in rich purple velvet – in the lounge. When I wasn’t sewing in that chair, I was reading those books I found in the bookcase. I feasted on them, absorbing words like a sponge. When I read, it was like there was a movie in my head. Later in life, in my thirties, this trait proved rather irritating, as reading the Harry Potter books before the movies came out was a big mistake. Huge! It was as though every detail was already imprinted on my mind in glorious Technicolor, so it was like watching the movie for the second time.

My reading was more successful than my sewing. I tried to remember if I had ever actually made anything. There was a faint memory of a cotton bobbin with four little nails in the top and of spending hours winding the wool round and pulling it through like a knitted sausage. The little things that brought pleasure, which now, as I type a message to a friend on my phone, feels ancient in its very being. Those days weren’t without some pain, but generally they were self-inflicted, such as accidentally jamming my hand onto a needle when I had decided to use the arm of the chair as a kind of pincushion. Screaming and running out to the kitchen to where Grandad was, with my hand outstretched, all I wanted was someone to take the pain away. Grandad did that. He was so scared that day; his face as I came bursting through the kitchen door…but relief when he understood why, as later he told me that he thought I had stuck my hand in the fire. Very gently he pulled out the needle; he was always so tender and softly spoken.

If you were to ask me now what meals he made for me, I couldn’t give you a single example. I found it hilarious that he always made a cup of tea with sugar in. Yuk. My mum was diabetic, so there was never any sugar in the house, and definitely not in tea, but he seemed oblivious to this, and as he was so perfect in every way I always let it slide. Plus if I said I wasn’t allowed to have sugar, the secret stash of chocolate buttons that appeared every time I visited might have disappeared too. So I was not going to argue over a bit of sugar in my tea. If you argued about something, there was always a consequence – although I can’t imagine what kind of consequence my grandad would have dished out – but I kept my lips firmly shut anyway, just in case. When the chocolate buttons did make their entrance – silently, stealthily just ‘appearing’ on the table – I would move them next to the fireplace. Every now and then I would give the bag a squeeze, and as if on cue Grandad brought in a teaspoon to spoon out the warm, gooey decadence. Oh, my word. The beauty of it. Forty-nine years later I can still feel the beauty of that moment and the melted chocolate oozing on my tongue. It was magical.

My biggest regret is not asking Grandad any questions about his life. Only when I was being yanked round every posh house in the country after his death did I realise that he used to be a butler to Winston Churchill and other eminent lords and ladies. How could I not know something as big as this? Later on, I would look at my relationship with my own children and realise they didn’t ask questions about my life either. Why would they, when theirs hadn’t yet started and the anticipation of what was to come was exciting? I mean, I’m ‘old’ – everyone over forty (OK, thirty) is old, so my life would seem quite boring in comparison; plus, for most of the experiences, you really would have had to have been there. So, grandparents being as old as they are (somehow I never thought he would die, despite being ancient), how could their lives be of any interest to us as children? I was listening to Helena Bonham Carter the other day. I think she is the one who lived in a house next door to her husband. You know the one? Skinny actress. Hauntingly beautiful, like a female Johnny Depp. She was a guest on Louis Theroux’s podcast and was explaining that she had completed a documentary, interviewing older people – mainly her family – and said she thought all grandchildren should interview their grandparents. What a fabulous idea! I thought about that for a moment; but, with no assistance, I think my questions would have probably revolved around: ‘What do you do when I am not with you? If you don’t have a job, why do you only come to our house on Wednesdays?’ (I still say ‘Wed-nes-days’ in my head every time I write it out. Is that weird?) ‘Why don’t you have any teeth? Why do you drive so slowly? How did you learn to make a fire out of such small bits of newspaper?’ And all manner of other trivial things. Would any of those answers (with the exception of the fire making) elicit a response around being a butler for the gentry?