PROLOGUE

William F. Coyne, CAPT, USN (RET)

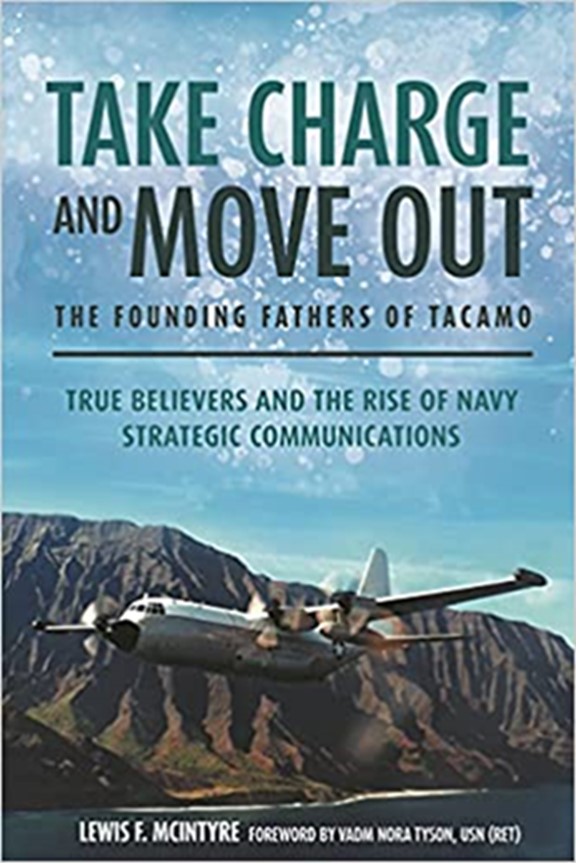

TACAMO, which stands for “TAKE CHARGE AND MOVE OUT,” is the Navy’s strategic airborne communications program for directing and managing the nation’s nuclear forces. It came by this name from then LT Jerry O. Tuttle, who later became an Admiral, and had his own major impact on Navy Command and Control. He was working in the Pentagon in the early sixties, and a Marine General gave him the task of setting up survivable communications to the then-new Polaris Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) forces. The general ended the meeting with, “That’s all, lad, now Take Charge and Move Out.” That hand-scribbled acronym became the TACAMO program, and culminated in the standing up of two squadrons, Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadrons THREE and FOUR (VQ-3 and VQ-4) in 1968, flying specially-configured EC-130s in the Pacific and Atlantic basins.

The Naval Aviation community has never understood or dramatized the TACAMO community to the extent it has the other carrier-based and shore-based Patrol Anti-aviation community. Those communities operate synergistically with each other, and with the naval surface forces of which they are an integral part. TACAMO operates outside of that realm, supporting strategic forces which the rest of the Navy recognizes must always be in readiness, but like all of us, hopes will never be used.

The story of the significant underlying events affecting the success of this major strategic system exist today only as untold stories in the minds of participating observers. As one of the early commanding officer of one of the these squadrons during a time of great transition, I had the humble opportunity to observe and participate in one of the great transitions of this community, indeed its birth, and I feel obliged to document this event in TACAMO’s history that I believe unquestionably altered its historical course and assured its success for the next several decades.

That key event occurred when a cadre of very junior officers assigned to VQ-3 and VQ-4 during the early and middle seventies formed an unshakable belief that TACAMO was the only survivable and effective communications platform providing connectivity from the National Command Authorities (NCA) to the US strategic nuclear deterrent forces. That unshakable belief motivated these officers to choose second tours in the TACAMO community, knowing full well that doing so might well leave their Navy careers in shambles before they had hardly gotten started. Their decision to stay with the TACAMO program during their second and subsequent tours proved to be the keystone that established TACAMO as a warfare specialty, with its own unique career path leading to command, and its becoming an unprecedented Navy success story with an evolving strategic operational capability.

In the ensuing chapters we will examine the role these officers played in the critical evolution of the TACAMO program. To fully understand how their convictions evolved, we will attempt to recreate the steering winds of time and circumstance that affected the program during this period.

I ask all who review these observations to remember my use of the term “significant events” in this Prologue. I leave it to other observers to document the multitude and meaningful critical program accomplishments of those men and women who followed these pioneers over the next forty years, for their contributions have also been significant: they brought out a new airframe, acquired a major new mission and a new place in strategic command and control, and by large changes and small, kept the communications suite and aircraft at the cutting edge of technology and always battle-ready.

But this is the story of those courageous few who took that leap of faith to launch a community where none previously existed, and with no promise of personal success. We have chosen, therefore, to solicit each of them to tell their own story, beginning with myself.

The ultimate success of the TACAMO program rests with the advocacy and faith of this cadre of “True Believers,” as well as everyone else who contributed to the success of the program.

CHAPTER 1: BILL COYNE

AT THE BEGINNING

Orders

“Good morning, Commander. I have been advised by your detailer that you have screened for alternate command and will receive orders to Fleet Air Reconnaissance Four in Patuxent River sometime in the summer. This is a major accomplishment in your career and I am proud to be the one who give you this news. Good Luck in your new assignment.”

As I was returning to my office in the “E” Ring in the Pentagon, I pondered the meaning of those words, uttered just moments ago. Little did I know at the time how those words would change my whole world as a commissioned officer and aviator in the United States Navy. While I was pleased and proud beyond words, my innate inquisitive nature led to the inevitable question, “Why an alternate command selectee?” How were these decisions made? What did I lack in my career as a warfare specialist in Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) flying with fixed wing patrol (VP) squadrons? Could it be that the selection was made on the basis of a program fit not on the pecking order of ASW commands, and therefore not an alternate command per se? I never found the answer to that question. It was of no consequence because in the end whatever fate guided this decision, it resulted in the most gratifying tour in my Navy career with challenges met and meaningful accomplishments made, by a squadron of focused, highly skilled professionals. They taught me the true meaning of dedication and professionalism.

The Special Mission (VQ) designation was also perplexing to me as I expected a squadron whose mission was primarily focused on electronic surveillance, as were the other two squadrons with that designation, VQ 1 and 2, flying EA-3s and EP-3s collecting Electronic Intelligence (ELINT). If so, I surmised it was an aviation command, multi - engine (non-carrier based), required experienced navigational skills, probably a communication package that was a cut above VP requirements, and required a comprehensive knowledge of associated surveillance tactics. However, my orders did not assign me to any schools in this genre.

I was mistaken. The Navy’s choice to designate the TACAMO squadron as VQ could have been misdirection, plausible, because one story ran that our aircraft was borrowed from the Marines to practice tanker tactics (referring the drogue) for support of Navy multi-engine refueling. More likely, the Navy just did not want to define a new squadron designator for what was envisioned to be a temporary stop-gap program.

For reasons I cannot recall, I made no further efforts to research the TACAMO mission, nor did I receive any information from the squadron as to their mission. It was not unusual for me to react in this manner as I was one of those unique aviators who believed that the Navy, specifically my detailers, knew best, so I always went with the flow. I recall that when I was ordered to the Pentagon it was to be in support of the SARS effort. I assumed this to be Search and Rescue (SAR), not far-fetched to me because of my VP background and carrier experience. It turned out that SARS stood for Selective Action Reports System, in the OP-90 Planning, Programming, Budgeting System (PPBS).

As far as I was concerned VQ was VQ, it is what it is. Fifteen years later as a third year law school student, I began to understand the logic of how the Navy assigns senior positions on the basis of experience, performance, and fit, even in the absence of previous assignments in the warfare specialty. My professor noted that upon graduation and acceptance to the bar, no matter ten minutes later or ten years, you are assumed capable of doing the job. With regard to Navy practice, that concept is borne out by the practice of assigning fighter/attack officers selected for prospective carrier command to command deep draft replenishment ships in preparation for taking command of a carrier.

The question to be answered is, “Did the TACAMO program suffer for lack of ‘home grown’ senior officers?” The answer is both yes and no! The yes/no answer rests with timing.

At the time I took command, the squadron was approximately six years old. Second tour Lieutenants (LTs) and Lieutenant Commanders (LCDRs) should have been rising up as mission-experienced officers ready to take the reins and grow the TACAMO concept. That had not happened by the time I arrived in the squadron in 1973.

Why did it not happen? The simple answer was that the TACAMO was not yet recognized as its own unique community, an essential element in United States strategic deterrence arsenal. Many still considered airborne transmission of high-powered Very Low Frequency (VLF) signals from a specialized aircraft to submarines, using a complex orbital maneuver for best water penetration, would be a cumbersome and unreliable method of providing highly available jam-resistant communications to the FBM force. They considered TACAMO to be an interim program, soon to be superseded by Project Sanguine land-based Extremely Low Frequency (ELF) and water-penetrating blue-green lasers, neither of which ever lived up to expectations. And interim programs did not merit a warfare specialty that would lock junior officers into a career path supporting a program that likely would not exist when they rose to command. Accordingly, most of the junior officer “bright stars” assigned to TACAMO program up to the late seventies chose “one and out,” leaving TACAMO for the more promising fields of VP aviation.

TACAMO efforts probably did not suffer greatly during this period from “alternate command” CO/XO selection from the VP community as much of the VP experience of aircraft deployment scheduling, maintenance, training and crew concepts were directly transferable from the VP community. However, in my opinion, the CO/XOs lack of familiarity with the intricate TACAMO mission technical issues restricted their ability to maximize TACAMO’s potential.

The real loss came from the continuous hemorrhage of corporate knowledge of these unique issues, as junior officers exited the community after a single tour, taking their operational experience with them. This loss was particularly critical at the mid-level management, the senior LTs and LCDRs. While alternate command was a viable and necessary means of generating the necessary COs and XOs, the mid-level department heads were all too often LCDRs passed over for promotion and command in other communities, with no future but a mandatory exit from the Navy after twenty years’ service. Many nevertheless served with distinction; others were reluctant to rock the boat.

Loss compounds as the years wear on. If left unchanged from this inauspicious beginning, the TACAMO program could not have achieved the status it enjoys today, and indeed might not even exist. The turning point came in the coming about of the “true believers”, those officers who steadfastly believed that “one and done” was not an option.

The Arrival

After a three month delay in my Pentagon departure, I was off to Little Rock for training in the C-130. I took to this aircraft, and it became a love affair to the end. This reliable platform and its stability in the orbiting maneuvers served the TACAMO mission well and positioned it as a thoroughly tested strategic capability until airframe age forced the transition to the E-6A. Training complete, I reported onboard for duty. After a cordial welcoming onboard, I was initially assigned as the maintenance officer, since I had arrived with several months overlap with the XO and CO. I determined later that there are sensitivities associated with a third command selectee onboard who was not assigned to a specific responsibility. Maintenance Officer seemed to be a good “stash” for me, though there were several mid-level senior Limited Duty Officers assigned to the department who were thoroughly trained and uniquely qualified for the position. I accepted this tasking without reservation, notwithstanding my desire to receive additional qualification as an Airborne Communications Officer (ACO) and have a reasonable command of the challenges faced by this position. That, in itself, would have been a most unusual ticket for a pilot to have punched, since that is a Naval Flight Officer (NFO) qualification.

Stand Down

At the time of my arrival, the squadron had been maintaining one hundred percent airborne coverage for several years. This meant that twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, there was always one aircraft airborne, survivable and ready to transmit any force orders to the FBM force. Elaborate procedures and communications protocols and networks had evolved to provide highly reliable command and control to direct the off-going airborne aircraft to fly to Prudent Limit of Endurance (PLE), the TACAMO watchword, until the relieving aircraft or a ready duty alert replacement aircraft could launch. But one hundred percent airborne coverage required a minimum number of aircraft to sustain this effort. The TACAMO program was undergoing a major modification program to the TACAMO IV configuration, and a year earlier, the squadron had lost one airframe, though fortunately no people, when BUNO 890 suffered a fire in flight and crash-landed on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Even after borrowing from our sister squadron VQ-3, which did not at that time maintain one hundred percent coverage, our aircraft assets fell below that critical number. So, not long after my arrival in the squadron, the order to stand down from one hundred percent airborne coverage was issued in order to transition the squadron to the TACAMO IV platform.

It was a devastating event for the CO. This officer ran the 100% airborne operation with great skill, pride in ownership, and an unquenchable fire to prove the system. He was an avid reader, impeccable researcher, and a well-respected representatives of the TACAMO program to his superiors and to several commands in Europe. The finesse of achieving a sustained 100% airborne program with limited aircraft and a restrictive supply pipeline was remarkable in itself; to retreat from this finesse seemed to be a step in the wrong direction. I was privy to more information from my Pentagon tour about competing programs like Sanguine and the blue-green laser than others, and it gave me pause to consider that I might be the one overseeing the final stand down on my watch. I can only imagine what the “one and out” junior officers were feeling at this time. Hindsight is great, but funding alternatives are difficult. I can’t help but wonder what the outcome might have been, had the Navy considered purchasing or borrowing aircraft to go through the Collins company’s refit program without having to interrupt a well orchestrated strategic system of one hundred percent coverage. One could speculate that uncertainty about the program’s future was in the decision equation.

The Game Changer

Random flights at about fifty percent airborne coverage were now the order of the day. Crew rest at various stops were increased as each crew relinquished their aircraft to an awaiting crew and then enjoyed leisure awaiting the next crew in with an aircraft to take them home. Frequent make-up flights out of Pax River were common and provided great flexibility to PLE limitations. While it was a less stressful, the loss of the mind set and absolute necessity to have an aircraft in the air twenty four hours a day had a negative effect on morale, as pride of achievement transitioned to a “country club” existence. Because of this change and the fact that less aircraft were available to the squadron, the pressure was “perceived to be lessened” in regards to meeting routine scheduled flights. Cannibalization, borrowing good parts from non-flying aircraft to repair another, was in excess of one hundred per month and the supply system could not meet the challenge. Flyable aircraft would come into mandatory checks and would be stripped for parts, requiring weeks to get them flyable again. Thanks to the Air Force, the C-130 parts found their way back into the TACAMO aircraft, but it took a great deal of effort from all hands, and permission from a single point of authority, to remove any working part from an aircraft, to reduce the cannibalization rate to less than one per month. This provided the new CO greater aircraft availability while transitioning to the TACAMO IV aircraft continued.

A major turning point in the midst of this debacle happened in October 1973, when the Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur war took a turn for the worse, Soviet intervention appeared imminent, and an elevated global Defense Condition (DEFCON) THREE was declared. The situation demanded one-hundred percent coverage that could not be provided by airborne assets. The crisis required improvisation, and the answer was the TACAMO War Watch. For about twelve hours before a scheduled flight, an aircraft and half the crew would bring up circuits on the ground, ready to launch if necessary. At the end of this period, the aircraft and full crew would fly an airborne mission then recover, and the other half of the crew would post the War Watch after refueling the aircraft. Therefore the community was able to provide one hundred percent communications coverage, though not airborne. As arduous as this routine was for several weeks, it did much to reverse the deteriorating morale, and remind all of the mission’s criticality. And our ability to improvise to achieve what seemed to be the impossible was not lost on the senior Navy leadership.

The Turning Point

Following the change of command, the squadron settled in to a reluctant, but accepted, reduced mode of operation. Various operational changes and new deployment sites enhanced TACAMO's flexibility and strategic response. The squadron’s workload was greatly increased as the TACAMO IV training programs were not only for VQ-4 personnel but also VQ-3 personnel, which would transition after us on Guam.

It is accepted that each commanding officer brings their own perspective and goals to the table when they assume command. Each generally can sum up their achievements accordingly. Few, in my experience, have the same outlook on how to achieve their goals.

Comments

Clearly a work of some…

Clearly a work of some scholarship and great attention to detail. The problem is it's so 'niche' that it has to have limited appeal.