CHAPTER ONE

Between Bondage and Freedom

The cool, salty breeze off the Chesapeake Bay that flowed over Fort Monroe had a stench that left an indelible memory of his self-liberation ordeal on Parson. He survived the two-day frigid trek in cold weather that required safely crossing both the icy Nottoway and the Blackwater Rivers to reach refuge as a contraband camp near Fort Monroe. There, the Union Army fed, clothed, and sheltered him in a refugee camp as a contraband of war. Parson never forgot the accentuating stench that flowed over Fort Monroe and punctuated his military service tenure.

Between bondage and freedom, the brothers not only endeavored to win their freedom during the war but also made vital contributions to the Union victory and ensured they got it. By December 1864, the contraband camps near Fort Monroe, Virginia, had become important recruitment centers for Black troops and civilian workers willing to dig trenches, build fortifications, and aid the Union cause on many fronts. A new relationship emerged between the national government and freed Black people, which slaves had lacked before the war.

During the period between bondage and freedom at Fort Monroe, a new relationship emerged between the national government and freed Black people, which they had lacked before the war. Parson learned about the creation of the USCT regiments, a radical turning point in national military history. After Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, the Union began recruiting Black men to create and fill the new branch of Army fighting units, also known as USCT regiments. Parson never forgot or failed to mention the historical role of USCT regiments in contributing to the Union’s victory and ending slavery in the nation.

After recruitment for military service at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and awaiting enrollment, Parson and his brothers stayed at a refugee camp in nearby Hampton, Virginia. The Union Army offered him the opportunity to earn money to fight against the monstrous institution that had previously enslaved him. As a newly recruited member of Company I, 1st Cavalry Regiment, USCT, Parson, born enslaved and denied human rights, suddenly found himself not just a soldier but a needed member of the national government.

During December 1864, the Union raised close to the number of combat-ready USCT regiments needed for the conflict, but not always with racial fairness and equal treatment. Despite objections from Black leaders, the War Department insisted on assigning only White men to commissioned officer positions. When the Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops in May 1863, the Army and national government officials initially assumed that Black regiments would rarely participate in combat. As a result, the combat-ready Black soldiers endured a disproportionate share of labor and lower pay. By the time of Parson’s enlistment, Congress had passed bills equalizing pay retroactive and granted full and equal back pay for all Black soldiers.

Meanwhile, it was mid-December 1864, two weeks since the brothers ran away. Their parents, Solomon Sykes and Louisa Williams, were eager for information about the outcome of Parson’s self-liberation plan. Neither parent had received any reports of Parson and his brothers’ capture nor return to Southampton County, Virginia. They stayed in contact with Frances, Parson’s love interest, hoping she may have had information about his status, but to no avail. She remained faithful to Parson and resisted suitors with increasing confidence and skill to fight them off. Unknown to Solomon, Louisa, and Frances, Parson was still alive, waiting to begin his military service.

While enrolled and awaiting the start of training and muster, Parson and his brothers relaxed and rested after duty hours and days when they did not have to work. Parson spent his spare time browsing Fort Monroe and touring Southside Virginia. It was the starting point for the Union Army’s Peninsular Campaign in 1862 and General Benjamin Butler’s recent advance to Petersburg in 1864. They also spent time in Slabtown and other refugee camps near Fort Monroe, where formerly enslaved Black people built settlements.

Parson shared stories about the American Missionary Association, teachers who instructed formerly enslaved people in contraband camps during the Civil War. To his amazement, he learned the history of the great African kingdoms of antiquity, including plenty of kingdoms and empires spread across the African continent, which filled American Missionary Association history books. Parson read about the ancient kingdoms of Aksum, Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Kongo, and Benin. The American Missionary Association and White sympathizers believed education should be a top priority for formerly enslaved people and the best way to help them fully gain their civil rights. They founded over five hundred schools and colleges in the South and spent more money doing so than the Freedmen’s Bureau.

From discussions with the refugees, Parson heard that at the outset of the war, President Lincoln insisted that the conflict was not about freeing enslaved people but preserving the Union. He understood that the Emancipation Proclamation was a military step that paved the way for the permanent abolition of slavery in the country. In refugee camps, Parson observed the results of enslavement and how it dehumanized people far worse than he had ever imagined. Like an evil monster, slavery often resulted in violence, human rights violations, and genocide. It deprived both the enslaved and the enslaver of human qualities. As mentioned, for the enslaver, it led to shame that only intensified a feeling of low self-worth and led to their need to dehumanize and discriminate. For the enslaved, it took many monstrous forms to subordinate them through segregation, alienation, and dominance by a web of customs, rules, and laws.

With those discussions, Parson recognized the various situations of the self-liberated Black people he encountered as an adult. From his viewpoint, Parson rationalized three very distinct situations of Black people engaged in the war: the former enslaved Black people of the South, the free Black people of the South, and the free Black people of the North. The free Black people of the South classified themselves based on their visible mixed-race features; the free Black people of the North aligned themselves to differences in religion, education, birthplace, and many family conceits. As a formerly enslaved Black person of the South, Parson placed himself between the two distinct situations of the Black people he met. Though dealing with racism united Black people in various situations, President Lincoln needed to develop political, economic, and social steps for the permanent abolition of slavery in the country. Like the ancient kingdoms of Africa he read about, Parson recognized that the self-liberated Black people engaged in the war were not a monolith.

As Parson developed into adulthood, the refugee settlements and the situations of the people who lived in the camps showed him the significance of his self-liberation ordeal. He often talked about the resourcefulness it took for formerly enslaved people to gather their families beyond Union lines, build information networks, pray, eat, give birth, share living space, and care for each other’s children outside a household setting.

One of Parson’s closest supporters at Fort Monroe was Shugar Sykes, a biracial person allegedly related to Solomon. He helped get a letter with a status report to his parents and Fannie. As a free Black person of the South, he traveled and learned through the grapevine that Parson was alive at Fort Hamilton and informed Solomon and Louisa. Jacob Williams tried to arrange the brothers’ return to Southampton County, but to no avail as other enslaved people prepared to flee, like Parson.

In the winter of 1864-65, conditions in the contraband camp were squalid, and disease was common. The refugees lived in constant fear and terror of raids from southern Whites. Thousands of Black men joined the Union armed forces, making up ten percent of the Union fighting troops. For Black people in general, the Civil War was a fight for freedom from the land of bondage, but for a time, those seeking to be free had to fight for the right to fight for their independence first. As Parson would eventually realize, finding freedom from the land of bondage was a formidable mission.

According to Parson, the Confederate Army plundered and burned down the huts that the refugees built for themselves in Slabtown at one point. He told how the Confederates posed an even more significant threat. Confederate soldiers raided the camps, and fugitive slave catchers roamed along their perimeters, waiting for an opportunity to capture refugees and haul them back into bondage.

Parson often recounted how Black soldiers received unenviable treatment from many White comrades-in-arms. They ridiculed, jeered, and taunted Black soldiers on the way to battle. According to Parson, he learned much about what to expect during his enlistment from the other soldiers with more time in service. They alerted him that White Union officers often placed USCT regiments in greater jeopardy than their White counterparts, with higher mortality rates.

He learned Confederates often killed Black soldiers if captured, and of those placed in Prisoner-of-War (POW) camps, only a few survived to be set free at the end of the conflict. The South did not give wounded men proper medical treatment. It refused to recognize Black soldiers as POWs, treating them as insurgent enslaved people, so it excluded them from prisoner exchanges.

Parson often talked about the resourcefulness it took for formerly enslaved people to gather their families beyond Union lines, build information networks, pray, eat, give birth, share living space, and care for each other’s children outside a household setting. Slabtown brought together people who had previously had no contact with each other, exposed them to massive forces much more extensive than their human ability to manage, and led to unexpected outcomes. The Black refugees in contraband camps affected the course and development of the Civil War, promoted the progress of emancipation, and enhanced the relationship between formerly enslaved people and the national government.

Parson had never met so many former enslaved people of distinct cultures gathered in such concentrations with the possibility of freedom so close. The exchange of ideas, traditions, and rituals fostered literacy and led to religious revivals. Whites also lived in the camps, most seeking shelter from the war. However, they received different treatment than provided to Black people. But despite the hardships and oppression, Parson recalled how the refugee camp offered the formerly enslaved people their first opportunity for freedom. He said the site let families reunite and laid the groundwork for a new society.

Parson and other Black troops got involved with the refugees and volunteered to help them improve or build shelters in the camps. The Black refugees in Hampton, Virginia, built schools, houses, and other buildings so sturdy that the Union Army later appropriated them to accommodate the troops. Another strong aspiration was to get an education and freed people wasted no time helping to establish and attend schools. In Hampton, Virginia, formerly enslaved people assembled under an oak to learn from teachers, such as the local free Black woman Mary Peake. According to Parson, there were four Black schools in Hampton; one became the future site of Hampton University, one of the country’s earliest historically Black colleges and universities.

As Parson described conditions, the shelter was also deficient. The contraband enslaved people who sought freedom at Fort Monroe crowded into any available space, from packing crates and unused rail cars at Slabtown to abandoned shops, houses, and outbuildings. In the free Black communities established before the war, Black people took in as many freed people as possible. Still, many were already living in tight quarters, so it was not long before numbers exceeded even the most generous welcome.

Addressing basic humanitarian needs was the most fundamental aspect of the quest of the formerly enslaved people seeking freedom at Fort Monroe. Hampton incubated a new relationship between Black people and the government. Hampton’s men, women, and children typically arrived after making risky escapes. Some had fled with possessions—frying pans, rowboats, or livestock. Still, many were destitute and in a weakened state caused by the harsh conditions of their enslavement, compounded by the wartime shortages and sometimes going for days without food or shelter as they escaped.

Most enslaved people who arrived at Fort Monroe often required food. The men, women, and children arrived at the Union lines lacking the subsistence to keep themselves alive. In the camp, the availability of Union Army rations usually meant that food was not scarce, but it was often monotonous and of scant nutritional value. Like the soldiers’ allotments, the percentages for freed people were starchy flour or hard bread, cornmeal or hominy corn, supplemented by salt pork or dried beef.

The lack of clothing was also a principal deficiency of contraband for enslaved people seeking freedom at Fort Monroe. Many slaves, especially the agricultural workers who comprised most of the enslaved population, only owned one or two clothing suits, so they arrived at the Union encampments almost wholly destitute. Clothing wears out, so it was only a short time before freed people’s garments tattered, as Parson observed.

Contraband men could wear cast-off Union soldiers’ uniforms. Still, there needed to be a ready supply of clothing for women and children, who instead relied on clothes donated by philanthropic organizations. In other instances, freed people fashioned clothing suited to their tastes from bolts of cloth sent by northern donors. Freed women in Hampton sewed dresses and aprons out of gingham or calico when they could get it, but they also tailored garments out of mattress ticking when all was available. Yet their resourceful demand consistently outstripped supply. Freed women lined up for donated denim, calico, and flannel as soon as it arrived, but there was never enough for everyone.

According to Parson, formerly enslaved refugees in the contraband camp faced dangerous conditions, often worse than life on the plantation. They often endured abuse from Union soldiers, faced reprisals when Confederates infiltrated Union lines, and occasionally re-enslaved when their former enslavers came looking for them. Fleeing women and children increasingly arrived in the camps barefoot and hungry after long journeys by land and water. Sometimes, the suffering from hunger and cold was so great that freed people died by scores per day. Sanitation workers carried bodies out by wagon loads, without coffins, and buried them in a trench.

He recalled the lethal disease environments the refugees endured. Inadequate sanitation, swampy conditions, low-lying areas, and poor drainage made the camps breeding grounds for bacterial and viral illnesses and disease-carrying mosquitoes. Smallpox raged through refugee camps, which sickened and killed thousands of refugees and exacerbated the clothing shortage because people burned any garments that came into contact with someone suffering from the disease. Smallpox did not loosen its grip until the weather warmed in the spring. But even then, the respite was brief because once summer came, mosquito-borne diseases and yellow fever proliferated.

As recounted by Parson, in January 1865, Fort Monroe had no fresh water, even after attempting to dig a nine-hundred-foot-deep well. All buildings, from town squares to haphazard tents, were vulnerable to the terrible sanitary conditions of overcrowding and the hasty assembling of shelters in a war zone. Unfortunately, the filthy, foul mud and stagnant water in a deep hollow adjoining the contraband camp rendered the buildings beside it unhealthy.

Freed people in the camps also faced dangers from other humans. Soldiers fighting a war, not philanthropists or aid workers with humanitarian training, oversaw the contraband camps. Some assisted the freed people, and these interactions changed many, but others remained mired in bigotry and blamed enslaved people formerly as the cause of the war. Unable to imagine enslaved people as property owners, soldiers sometimes assumed that the Confederates owned any property the freed people brought with them and confiscated it. According to Parson, the superintendent of contrabands around Norfolk, Virginia, was treacherous toward freed people, sometimes robbing, beating, and selling them as fugitive enslaved people.

Because of volunteer help from troops like Parson, families in refugee settlements gained the strength, stability, and independence needed to create a better life. Once Black men enlisted in the Union Army, Slabtown became an instant recruiting station, and northern newspapers documented their contributions to the Union victory. The contributions of the women, children, and non-fighting men who labored for the war effort are less known. Parson spoke of how freed men, women, and even children dug, ditched, planted, weeded, hoed, harvested, hauled, distributed, laundered, cooked, nursed, scouted, and more for the Union war effort.

The Union Army’s Virginia and North Carolina Departments hired formerly enslaved people to repair and maintain rail lines, work on steamships, and load and unload cargo on docks. As Parson discovered during his escape, Black men and women regularly spied for the Union Army from miles within enemy lines, bringing back important, reliable information. They made excellent spies because they knew the local terrain better than the newly arrived Union soldiers.

Parson always enjoyed Christian fellowship and attended worship services in the contraband camp. However, waiting for him is a nation where institutional racism hides among everyday people, and social injustice can be as benign as a worship service. While he continued his self-liberation journey, Parson’s upcoming adversaries, the dreaded Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and its legendary commander, General Robert E. Lee, were nothing like any adversary he had previously encountered.

Against incredible odds, freed people strove to realize their aspiration of the realities of camp life. When compounded by medical quarantines or Union policies that separated soldiers from the camp inhabitants, they were especially challenging for the formerly enslaved people’s transition to independence. According to Parson, social life for formerly enslaved people who flocked to the contraband camp beyond Union lines included the established schools, churches, and hospitals that contributed to the social life in Black communities.

In September 1862, President Lincoln warned the Confederates that the national government would free enslaved people in states still in rebellion starting in January 1863. When he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil War evolved from a fight to preserve the Union to a War for Freedom. By December 1864, approximately one-half million formerly enslaved people and other Black freed people had sought protection behind Union lines. They seized almost every chance to pursue their freedom, often risking death, and helped make slavery a central issue of the Civil War.

The contraband camps played essential roles in the formerly enslaved people’s transition to independence. Their inhabitants made vital contributions to the war effort, from growing crops to working as cooks. The Army recruited many of the Black Americans who fought for the Union from the camps. Once the contrabands began establishing their communities, they went to work for the U.S. Army for two dollars a month. Many became officer’s servants or guides for Union movements throughout the Peninsula. Others were more inventive, oystering, fishing, and growing crops to sell food to the soldiers at informal markets.

Religion and religious observance played a unique role in the social life of the formerly enslaved people in the contraband camps. Seasonal festivities culminated during the week between Christmas and New Year, and several days were set aside as holidays. The formerly enslaved residents of Slabtown knew that the Emancipation Proclamation also concerned them. On December 31, 1864, Reverend William Roscoe Davis, a Baptist preacher, held a religious gathering with the refugees in the contraband camp. According to Parson, his sermon encouraged and inspired others to feel good about themselves and gave hope that the war’s last campaign would end slavery in the nation.

As Parson recalled, Reverend Davis was among the first enslaved persons to find freedom at Fort Monroe. He became an ordained minister in 1863 and was pastor at the First Baptist Church of Hampton. Davis preached at several meetings during the first winter following the Civil War and on January 1, 1866, at what was reportedly Hampton’s first public celebration of the end of slavery. The occasion, now known as Watch Night, is an annual New Year’s Eve tradition that includes the memory of slavery and freedom, reflections on faith, and celebration of community and strength.

In bondage, enslaved men, women, and children did all they could to protect their family and community ties since the government did not preserve social relations under enslavement. Because the enslavers had complete power over the enslaved, they had no relationship with a government that protected or provided them with any means of legal recourse.

In contrast, the contraband camps brought many enslaved people into direct contact and engagement with the national government through the Union Army. Formerly enslaved people used their proven usefulness to the war effort to bargain to protect their ability to pursue their ends and care for the things and people that mattered to them. If freed people tried to stay in a contraband camp without the Army’s protection, Confederates swooped down to re-enslave, beat, or even kill them. According to Parson, in 1864, when Union forces temporarily abandoned Suffolk, Virginia, a Confederate brigade swept through the region, shooting or bayoneting some freed people and barricading others into a building they set afire.

The national government and freed people always improvised their relationship, sometimes leading to tragedy and often remaining unstable throughout the entire war. Yet, it offered real, if imperfect, gains for all its shortcomings. When Union troops were present, freed people were safer from attack or re-enslavement, gained personal mobility, better protected their families, and had access to schooling and other social life that the law prohibited under slavery.

The new relationship also gave freed people access to legal rights, which slaves had lacked before the war. One was the right to enter contracts, such as those between the U.S. Government and hospital nurses. Another was access to the courts. According to Parson, in North Carolina, one formerly enslaved man got money from a White man by taking that man to the Army provost marshal’s court. Another formerly enslaved man got to keep his hog when a White woman tried to take it. Parson noticed that legal rights did not solve freed people’s problems but could sometimes yield practical benefits.

During the Civil War, Christmas Day was a way to escape from and be reminded of the conflict that divided the country. Parson and the other soldiers looked forward to a day of rest and relative relaxation. At Fort Monroe, the Christmas dinner in the mess area was excellent. Parson had never seen so much food and variety. General Butler treated his soldiers to foods such as turkey, oysters, pies, and apples. However, many Black soldiers received no special treats or privileges.

As Parson celebrated his first Christmas as a freed person, he likely reflected upon his previous life and a hopeful future. With the Emancipation Proclamation and military service by Black troops, he wondered if the nation would accept full citizenship for formerly enslaved people. Parson formed a vision for the future but had little hope it would ever happen without reducing racism. Parson realized the nation needed significant reforms or amendments to the Constitution to ensure fair treatment, political engagement with voting, and Black business ownership in Black communities. The nation would need reform to provide such support as educational, business, and land ownership assistance.

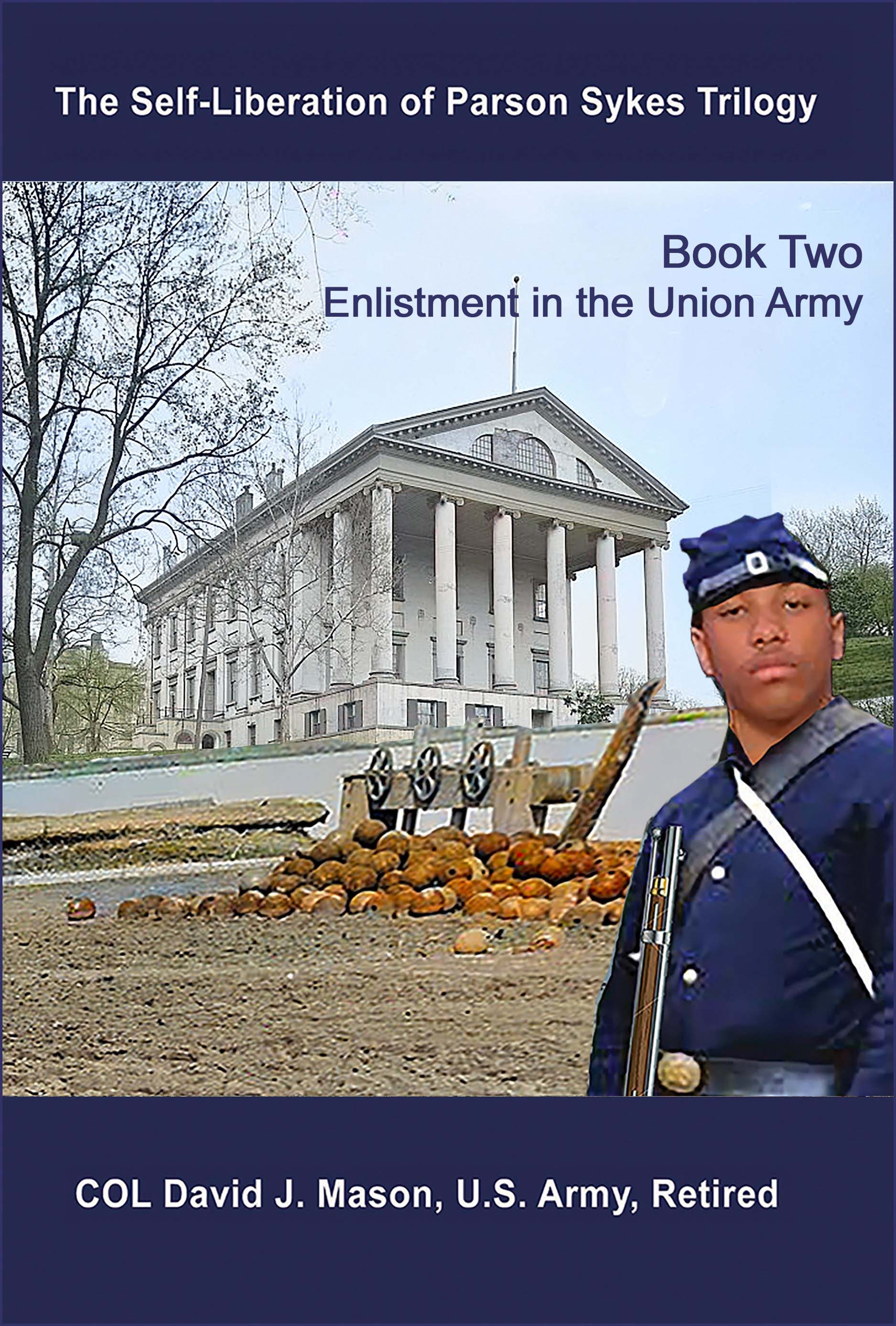

As a member of the 1st Regiment, United States Colored Cavalry, seventeen-year-old Parson, born enslaved and denied human and civil rights, suddenly found the national government needed him. The Union Army offered him the opportunity to receive money to fight against the institution that had previously enslaved him. En donned in the official Union blue uniform, he and his brothers made impressive gains in personal uplift and racial advancement.

Both Black soldiers and their White officers were outspoken about questions of race, civil rights, and full equality for the newly freed population during the Civil War era. In one discussion on December 25, 1864, during the Christmas meal, Parson and other USCT soldiers talked about the White officers who made inhuman, racist references to Black people regardless of their views on the abolition of enslavement. White officers did not want full equality for the newly freed population because they would have to compete with lower-paid Black labor. In addition, immigrants would find little hope for social advancement amid the hereditary aristocracy dominating Anglo-American society.

Being new to the Army, Parson did not want to argue with the officers, so reluctantly, he agreed to their comments. After a few minutes of eating, Parson realized what was happening. Not wanting to cause any disturbances, he just ignored the racial stances. That was Parson’s first introduction to racism in the Army, but not discrimination. For Parson, Christmas Day 1864 at Fort Monroe was a reminder of the monstrous melancholy that had permeated the entire nation.

Parson had some significant challenges ahead, which were too great for one person to face alone. In his view, the relationship between freed people and the national government created a channel to address Black people’s needs as the war closed. As he observed, the Union desperately needed help to maintain its uniform strength. According to Parson, over one hundred thousand Black people served in the Union Army. Their presence enabled Grant to embark on a course that promised the greatest hope of Union victory. In these ways, Black people contributed to the war effort and advanced their autonomy through enlistment and participation in the Union Army.

Lincoln based his stand on his authority as Commander-in-Chief. The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order written by Lincoln as a military measure: enslaved people were vital to the Confederate War effort. As Commander-in-Chief, Lincoln could hinder that war effort in any way necessary. This power included depriving Confederates of unpaid labor by liberating their enslaved people. It also had the enlistment of Black men in the Union army, a measure Lincoln later believed was decisive in turning the tide in the Union’s favor.

However, Lincoln went further than simply putting Black men in blue uniforms. He won reelection in November 1864 and afterward worked quietly behind the scenes to ensure his officers in the field treated Black people fairly and enforced reasonable labor conditions for formerly enslaved Black people in occupied areas. Lincoln publicly advocated Black suffrage in the last months of the war, something no previous president would have dared to contemplate. He encouraged the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, outlawing slavery forever. Regrettably, President Lincoln did not see the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Had Lincoln lived, it is reasonable to believe that, as Commander-in-Chief, Lincoln would have used the Union army as a powerful referee in the troubled new racial landscape of the postwar South. On March 3, 1865, Congress passed a significant act called “An Act to establish a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees.” The Bureau’s activities were to provide immediate relief and teach Black and White Southerners the true meaning of freedom and how to navigate their differing visions of life and labor in the new national order. This act was a testament to the nation’s commitment to social justice and humanitarian efforts. Parson welcomed the Bureau and how it undertook the formidable and unprecedented responsibility of safeguarding the general welfare of both liberated formerly enslaved Black people and White refugees.

Meanwhile, from December 1864 to January 1865, USCT soldiers of the Army of the James participated in the first Fort Fisher, North Carolina, campaign. Butler had one more chance for a military triumph. Wilmington, North Carolina, the last port of entry for supplies to the South, lay within his department. If he could seize Fort Fisher on the peninsula that was the key to Wilmington, the city would fall, and the Confederacy would face starvation. Butler developed a plan for putting the fort out of action by exploding a ship full of gunpowder directly in front of it. Butler used his position as the commander of the Army of James to assume personal command of the expedition.

Grant took a dim view of the plan but allowed Butler to try it. Butler insisted on leading the combined land-naval expedition himself. When it came, the explosion was so ineffective that the Fort Fisher garrison thought a blockade runner had burst the boiler. Only one-third of the 6500 USCT soldiers Butler took to capture the fort landed on the shore. These were enough to have captured Fort Fisher, but it appeared Butler had again lost his nerve. Alarmed at the news that the defense was receiving reinforcements, he ordered an abrupt retreat. The sudden movement stranded seven hundred of his men, who had to be rescued by the Union naval part of the operation.

After his failure at Fort Fisher, Grant relieved Butler of his duties. Major General Alfred H. Terry, who replaced Butler, assumed command of the expedition and led the follow-up joint operation against the fort.

Comments

With regards to style and…

With regards to style and content, it reads like an excerpt from a history textbook. As interesting as it is, I think the focus is a bit unclear and I would suggest the writer decides whether this is about 'Parsons' himself or about his role in the army generally.