The Stars In April

CHAPTER ONE

Guntur, India

March 7, 1912

Morning

The train whistle gave one last piercing proclamation. Ready or not, Ruth Becker, your journey begins now!

Perched next to me on the edge of the middle seat, Marion laughed and covered her ears. I rubbed at the train’s grimy window with my sleeve. Would Papa and Sajni still be waiting on the platform?

Wiping away tears, I spotted them outside just as they found my window. They waved, and Papa blew a kiss.

How can you let me go, Papa?

Mother scolded me from her seat on the aisle while Richard squirmed in her lap. “Ruth, you’ll dirty your coat! Better take it off. It’s much too hot.”

Standing beside Papa, Sajni tossed her thick black braid over a shoulder and wiped her own eyes, even as she smiled for me. As one of the oldest orphans under Papa’s care, Sajni would share a rickshaw back to the orphanage with him.

I clutched the bag that held the quilt she’d given me in the station. For months, I’d watched her stitch together the work of art, not knowing I would soon be forced to leave India forever and Sajni would insist that the quilt go with me.

I should have been home, practicing my violin before school rather than sitting aboard a hot train bound for the coast. This was all Richard’s fault. If he weren’t sick, then we wouldn’t be on our way to America. But how could I blame a two year old?

It was the Guntur doctors’ fault for not knowing how to cure him, then talking Mother into dragging him to America. To her, that meant we all would go—except for Papa—and I had no choice.

The last of the passengers boarded the train. Keeping my gaze on Papa, I hoped the three seats that faced ours would remain empty. The last thing I wanted now was someone else bothering me.

We had no idea how long it would take for the mission board to find another director for the orphanage. I’d begged to stay with Papa, listing a dozen reasons, including the violin recital at the Spring Festival. How could he let me miss it, especially after my years of hard work? But all my begging and bargaining had done no good.

The attendant led a man and a boy down the aisle, stopping at our row. My heart sank. There goes any chance of peace.

Before our train pulled into the station, the pair had entertained the crowd on the platform by juggling mangoes. The boy now clambered over our knees with his dirty shoes, and I grabbed my string bag and bedroll off the seat that faced mine just before he plopped down.

“Pardon us, ladies,” the man said, taking the middle seat next to the boy.

Mother squared her shoulders. She tucked her skirt in closer and glanced across the aisle at the last empty seats. Ten seconds later, an elderly couple claimed them. Too late now.

Freckles covered the boy’s nose and cheeks, and he made a great deal of commotion for someone so skinny. I guessed him to be around twelve, like me. He stuffed his basket of mangoes, a cap, and a blanket under his seat.

The exit doors banged shut, trapping us in. With another blast from the whistle, we lurched forward. I held my breath, watching my world disappear.

This is it …

Mother and Marion leaned over me and waved to Papa and Sajni. Both of them walked alongside the train, calling out words I couldn’t hear. Then our train picked up speed, they were gone, and I was left staring at the empty platform in the distance. When would I see them again?

Mother was all business. “Let’s settle in, girls. It’s going to be a long, hot day.”

The temperature soon rose in the compartment. I pulled off my coat and rolled it into a ball, ignoring the boy’s stares. Where was I supposed to put everything with my knees only inches from his?

Marion slapped her seat, making certain our brother knew she’d claimed it for eternity. “My seat, Richard.”

The conductor came along the narrow aisle, punching tickets row by row. His handlebar mustache was overly waxed, and he reminded me of Mr. Liddle, my violin instructor. He took our tickets from Mother and punched them, letting the tiny paper dots fall to the floor.

Richard’s cheeks were now red-hot. Mother removed his coat and unfastened his top shirt button. He let out a moan, a warning that a full-blown cry was not far behind.

While the conductor punched the jugglers’ tickets, Mother turned to me. “Hand Richard’s bag to me. It’s too soon for his medicine, but perhaps he’ll take some milk.”

I found the sack stuffed with all the supplies my brother could possibly need for the two-day train ride to Cochin, give or take a few months.

Marion yanked off her coat. “Can I have my book, Sissy?”

“May I have my book.”

Richard took his bottle as Mother fanned him, causing his wispy blond hair to wave in the breeze. She lowered her voice and glared at me. “You need to be patient.”

How could she have said that today of all days, when all I wanted to do was turn around and go home?

The train charged through an open field. Marion occupied herself with an animal book, leaving me to stare out the window. Cotton and poppy fields blurred like an endless Impressionist painting.

I used my sleeve to wipe the perspiration from my forehead. The rhythmic swaying of the train car soothed me like a lullaby, and my eyelids soon grew heavy.

I led Sajni by the hand to the swings on the orphanage playground. “Want to swing?”

She watched while I showed her what to do. “Nee peru yenty?”

What did she mean?

She pointed to me. “Nee peru yenty?”—she pointed to herself— “Sajni.” Then she pointed to me again. “Nee peru yenty?”

I understood. “I’m Ruth.”

The train whistle blew, and I jerked awake.

“Who’s Sajni?” the boy asked, in a thick British accent. “You said the name.”

Mother and Richard dozed in the aisle seat, and Marion had fallen asleep with her head against Mother’s arm. I scowled at the boy. “I was dreaming, that’s all.”

He opened his book as the juggler man snored beside him. I found my journal and drew flowers in the margins as I recalled the dream. Instead of growing up with Sajni by my side, I was bound for the Indian coast against my will. But nobody cared.

I loosened my shirtwaist collar and pushed the sleeves past my elbows. India’s heat had never bothered me—it was all I knew. But until now, I’d never ridden inside a jiggling steel cave stuffed with sweaty travelers.

Most of the passengers looked to be European. They read, fanned themselves, or dropped their heads back with eyes closed. The juggler man snored loud enough to drown out the train whistle, and—thank goodness—the boy kept his attention on his book. I didn’t feel like socializing.

How were we supposed to have any privacy, let alone sleep in our seats that night as we all faced one another? I fiddled with the rusted window latch. With a couple of shoves, the window gave way a few inches. At least the hot air outside was more bearable than the stench of body odor.

“That’s some breeze,” the boy said. His accent almost made English sound like a foreign language.

He laid his open book in his lap. “What’s your name?”

I knew few boys in Guntur and even fewer pushy ones. If I told him my name, maybe he’d leave me alone. “Ruth,” I said, folding my arms and concentrating on the terraced rice fields that zipped by the window.

“I’m Michael Frank, and this is me dad.” He jerked his thumb toward the snorer. “We’re from Biggleswade. That’s in England.”

Mother cleared her throat, even though her eyes remained closed. I wasn’t supposed to talk to strangers.

But what if I wanted to talk to someone? Who was I supposed to talk to? My little sister?

The train jolted to a stop at a small station, pulling my family out of slumber. A faded schedule hung at a crooked angle near the station door, next to a dirt-encrusted window. Did all trains and train stations have dirty windows?

I groaned and let my head hit the back of the seat. Here was my last chance to enjoy the Indian countryside, and I couldn’t even see it clearly.

Several Englishmen stood on the platform in the hot sun, waiting to board. Their gray and brown suits blended with the dark building. How they could dress so formally in the heat of the day was a mystery to me. The loose tunics Indian men wore seemed much more practical.

A sour-faced man who carried a newspaper took the empty seat next to the snorer. He stuck an ivory-handled cane under his seat. Did he shoot the elephant himself? The train departed the station, and I turned away in disgust as he opened his paper.

Mother tilted her head back and closed her eyes. Richard fussed until he found a comfortable spot in the crook of her arm. Marion swung her legs up and down, nearly kicking the juggler, and turned a page in her book.

Michael Frank spoke again. “Goin’ to the States?”

Marion jerked her head up. “We’re goin’ to America!”

“Are you from America?”

I glanced at Mother. She was already breathing deeply and had relaxed her grip on Richard. “No, I was born in India,” I said. “But my parents are Americans.”

“You’re a Yank, then! I mean, American.”

“Yes, I suppose.” Why was he taking the conversation in that direction? I sure didn’t feel American.

Next, he looked at Marion. “What’s your name?”

She frowned and twisted her body toward me. Served him right. “I’ll tell you about us,” he said, “then you can tell me about you.”

Before I could respond, Michael Frank jumped right in. “Me and Dad, we’re in a travelin’ circus. We’re acrobats—The Great Frank and Son.” He flexed his wrist. “We spent a fortnight in Calcutta, and China before that.”

Even if he could juggle, he didn’t look like an acrobat to me. Not that I’d ever seen an acrobat, but he looked much too skinny, and certainly not old enough.

“Am I supposed to believe that?”

He raised his chin. “You can ask Dad when he wakes up.”

If he was telling the truth, and two real-life circus performers were sitting across from us, I would have to write to Sajni about it as soon as possible.

“All right,” he said. “It’s your turn.”

Mother barely opened her eyes, then she shifted in her seat to ease Richard’s head to her lap. Marion closed her book and lay back on Mother’s arm. The elephant poacher had drifted off as well.

Mother wouldn’t want me telling Michael Frank our business, but we had a long ride ahead. I inched closer. “My father is a missionary who runs an orphanage. I’ve lived in India all my life, but my brother is sick.”

I cast a quick look at Richard. A drop of milk drooled from his mouth onto Mother’s skirt. “We’re going to the States because he needs a good doctor. We’ll stay with my grandparents in Michigan until my father can join us.”

Michael Frank’s eyes widened. “You’re not coming back?”

More of my home slipped past the window, and an ache filled my chest as I told my story. “No, we’re not coming back.”

His dad stirred for the first time since boarding the train. His eyes peeled halfway open, and he ran his hands over his face and through his wavy hair.

Michael elbowed him. “G’day, Dad.”

The train zoomed into a tunnel, plunging us into sweltering darkness. Marion screamed and grabbed me. I dug my nails into the seat cushion and counted the seconds. The tunnel amplified the chooga-chooga-chooga sound of the train. When we emerged from the inky blackness, I squinted to find the cord for the rattan window shade and lowered it to block the glaring sun. Dust from the shade floated to my lap.

Richard cried out, waking Mother.

She leaned toward me. “Take Marion to the washroom. I believe it’s in the car behind us. Then we’ll have our lunch.”

“But how can I take her when the train’s moving?”

“You never been on a train b’fore?” Michael’s voice hinted at ridicule.

Mother blinked hard and pursed her lips like the knotted end of a rubber balloon. She stood, and with one quick move, stepped into the aisle and motioned for Marion and me to go … now.

Attempting to walk inside the moving train was no small feat. For a flash, I imagined I was a circus performer, balancing on a tightrope, until I stumbled into some seats. Marion lost her balance as well, and nearly tumbled across a woman’s ample lap.

We found the tiny washroom one car back, and the two of us struggled to fit inside together. The sour smell made my eyes water. Marion held her nose.

But the soap was sudsy, and the jug of water meant for rinsing looked clear. Still, I wouldn’t dare drink any water other than what we’d brought from home. I’d learned too much about the spread of cholera to take that chance.

We returned to find Michael’s dad smiling and talking to Mother as she studied him over the rims of her spectacles. She had our lunches spread out on cloth napkins.

Marion clapped her hands. “Hurray! I’m so, so hungry.” She squeezed between Mother’s and Poacher Man’s knees.

“Dad,” Michael said. “This is Ruth.”

“Very pleased to meet you, Ruth … uh, Miss Becker. We’ve just met your luvly mum and brother. I’m Robert Frank.”

Mother gave an exaggerated inhale at the “luvly mum” remark. My sister slurped water from her cup. “And this is Marion,” I said. “I’m four!”

At least she’d finally stopped holding up fingers to announce her age.

Mr. Frank pulled out a sack of food. He snagged a mango from the basket and peeled it with a pocketknife, sharing it with his son.

Michael noticed my stare. “When we’re done juggling ’em, we eat ’em.” He rubbed his short sleeve across his face. “On the train to Guntur, we climbed the outside ladder and sat on top of the fruit car. Cooler up there, for sure.”

Was that where their mangoes had come from? If only our train had a fruit car. I would’ve climbed out there too.

Our water was still cold, thanks to its metal container. So were the cheese, our own sliced mangoes, and vegetable dosas. How was I going to manage in America without dosas?

Mother helped Richard eat a chunk of mango. “Tell me, Mr. Frank, what kind of work do you do besides juggle?”

He perched himself on the edge of his seat. “I work for a circus, Mrs. Becker. Michael and me are partners. We’re an acrobatic duo—The Great Frank and Son.”

Michael thrust out his chest. The expression on his face said, See?

“Oh my, circus acrobats?” Mother used her most polite voice. “How very … interesting. What about school, Michael?”

“I have a tutor sometimes, or Dad helps.” He held up his book. “Plus, I read and do sums on the road.”

So their story was true, and I was riding a train with a skinny, freckly acrobat who juggled mangoes in his spare time. Wait until Sajni hears this!

“Did you ever go to a real school?” I asked.

“When I was little, before I was big enough to work with Dad. B’fore me mum died.” Michael looked down and bit into his sandwich.

“It’s been four years,” Mr. Frank said, “and we been on the road ever since.”

I swallowed a juicy bite of mango. “Are you going home to England now?”

“Yeah, for eight weeks,” Michael replied. “We’re not on the doss. We’re the only Brits in the circus, except for the elephant trainer and the tenters.”

“While we’re on our break,” Mr. Frank said, “we’ll work on our trapeze act. We practice with other blokes at a barn near our house.”

“And tumblin’, Dad.” Michael turned to us. “I’m workin’ on a triple back flip.”

Mr. Frank nodded. “Then we’ll pick up the circus in Germany and work a handful of cities in Europe.”

I tried to picture this scrawny boy doing a triple back flip. Mother bit her lower lip, clearly having trouble understanding the Franks’ strange life.

Poacher Man woke, coughed, and looked about. He adjusted his wrinkled suit and pulled out a handkerchief to mop his brow, then he felt around for his cane. He got to his feet and scanned the aisle in each direction. Mr. Frank pointed the man toward the washroom.

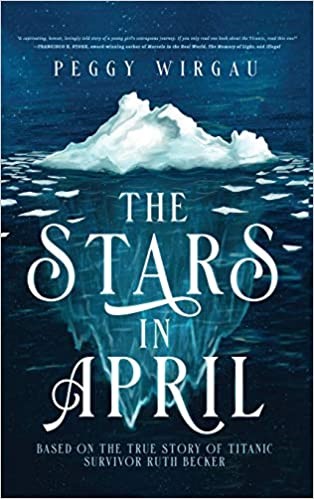

I glanced at the newspaper on the man’s seat—The Daily Telegraph, an imported British paper. An advertisement for the RMS Titanic filled a quarter of its front page.

The day Mr. Liddle asked me to play in the festival, I felt as though all my dreams had come true. “Spring Song” by Mendelssohn was a difficult piece for violin, but Mr. Liddle had wiggled his index finger at me and said, “You are becoming quite an accomplished violinist, Miss Becker. One day, you may be ready for the Calcutta Orchestra.”

That was before my parents had informed me about Richard, and Papa tried to make amends with tickets to America on White Star Line’s newest luxury liner.

I stared at the ship in the newspaper advertisement. There would be no festival for me now. And no orchestra.

Everything had changed.

Comments

Different point of view of a well-known story

Nice way to re-imagine a story so well-known. Good job with that.

Thank you, Robin!

In reply to Different point of view of a well-known story by Robin Cutler

Thank you, Robin!

Congratulations

Well done on making the long list. Love your story. Old days and trains, I can really feel the atmosphere. Be good to read the rest. I'd enjoy a ride on the Titanic from a fresh perspective.

Thank you so much, Jerry!…

In reply to Congratulations by JerryFurnell

Thank you so much, Jerry! Congratulations to you as well. I love the opening line of your submission. Good luck!