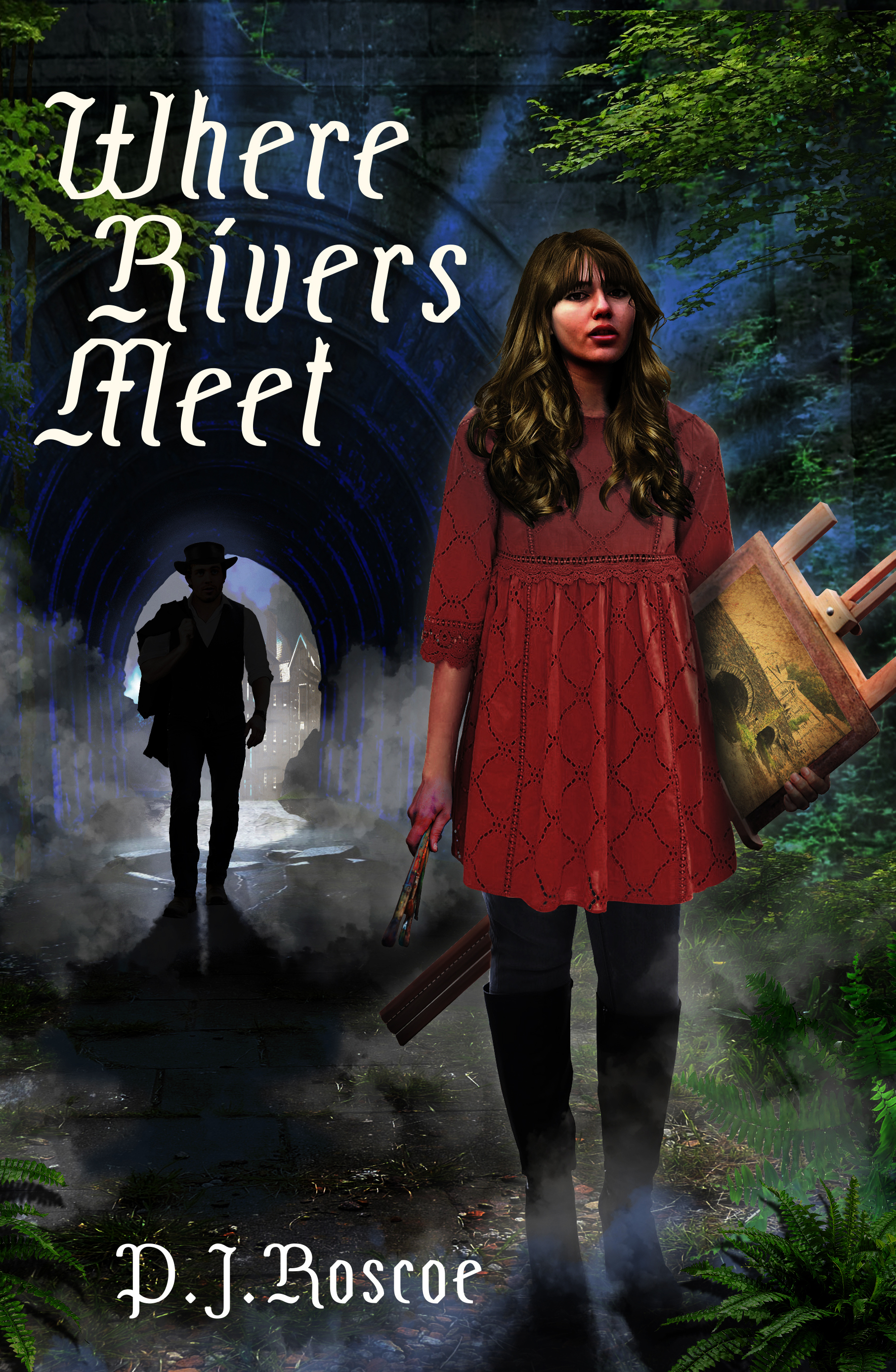

Where Rivers Meet

Prologue

The sun had left its warmth on the day. A slither of golden light streamed along the line of slate roofs while the rest of the small cottages lay in semi-darkness within the shadow of the mountain. The pubs were busy with people laughing and smoking both inside and out. Some stood in the road knowing the traffic would be minimal at that time of day. The café and the shops were closing late as the summer punters began to make their way home. The village was settling down after yet another long, hot day of tourists, and now the villagers could relax a little, until the next onslaught of coaches and sightseers.

The dark grey stone of the buildings nearest the river shimmered. Even the small stone bridge looked alive as the rays bounced off the grey boulders in the shallow water beneath. Darkness was a while away yet, but for the few birds singing their last song of the day, it was still. The voices carried across the river from the pub, blending into background noise, a gentle hum, not intrusive. The whole place was, for just that moment, frozen and no one else existed.

My blue cardigan dragged along the path, barely remembered as it hung between my thumb and finger. I vaguely acknowledged a shout from the pub ‘that I should get home quickly or Nan would be worried’, but I was busily picking through the day I’d just had, pirates and princesses.

The den, or ‘castle’, had taken up most of the morning to build, and then hungry, sweating and dirty, we’d quickly eaten our packed lunches only to resume our play of ‘pirates rescuing princesses’ which had taken up the rest of the afternoon. Our play consisted of swimming and sword fighting, climbing and swinging on the tattered rope the adults had said was a severe health and safety risk, and lots of running around barefoot, dodging the large cow pats that littered the field.

As the afternoon wore on, it was Dafydd who’d finally voiced what we’d all secretly been thinking. It was time to go home and have tea, slump in front of the television, and go to bed.

It took less than half an hour to get back to the village because we’d played an impromptu game of tick on the way. Arriving on the stone bridge breathless and glowing, we’d waved goodbye, with a few of the boys playfully punching each other in the arms. We agreed a time and place for meeting tomorrow and scattered like rabbits, each to our own homes, or in the case of Chris and his younger sister Annie, to their holiday cottage. My Nan’s cottage was one of the last on the outskirts of the village. My stomach growled loudly—my Nan always had something delicious cooking in her oven—and I could hardly wait; my mouth watering.

Nan baked pies and cakes for the locals to buy from her front porch and from her spot in the local market. Many a wedding, christening, or funeral had been graced by her cooking; she was famous. Well, famous in this small area of Wales anyway, and that was good enough for me. I was proud of my Nan and wanted to be like her.

I glanced up at the sky and smiled, the whole summer stretched before me; autumn was very far away. So was my family home in Chester where my younger brother Ben and Mum and Dad were happily going about their lives without me. I didn’t care. I never got homesick. I loved it here in Beddgelert and waited impatiently for the summer holidays when my family would drive up and leave me with Nan.

Every summer I came to stay while my parents had a long holiday of their own. When Ben was born, I’d expected him to ruin the holidays by coming too, but thankfully, so far, he preferred to go abroad with Mum and Dad. This year they’d asked yet again if I wanted to go with them, (this time to Greece) and I’d flatly refused.

The four weeks I spent in Wales were the best of my life and I dreamt of living there permanently. Nan never demanded I wash or brush my teeth. She never told me off for being dirty or noisy, and never asked me where I was going or when I’d be home. She had no reason to. Everyone in the village knew where we were anyway and kept an eye open for any trouble. Most of the village children had accepted me as one of them, and this pleased me greatly. I was inspired to learn the Welsh language, and each year I became more confident in using it. The locals called me ‘Abbie cariad’, meaning ‘darling Abbie’.

I stopped and leant on the low stone wall and gazed down at the river, smiling. The water glistened like tiny diamonds, blinding me as the last rays of the sun bounced upwards. The air shimmered, and I closed my eyes against it for a moment and turned away.

He stood on the opposite side of the river, watching me, his hands in the pockets of his black trousers. He wore a white shirt, open at the neck with his sleeves rolled up, and he wore braces. His eyes met mine, and he smiled. I smiled back before remembering the golden rule, ‘don’t talk to strangers’, and guessed that also included smiling, and I hastily turned away and continued onwards towards Nan’s cottage.

I could see her in the distance. She was talking to a woman from the village. Nan saw me and waved. Waving back, I stopped abruptly; something was wrong? Turning round, I glanced back across the river, a cool breeze bringing goose-bumps to my skin, and I clung to my cardigan as I stared across the water, the silence intense. The very air seemed to be holding its breath as I looked to where he had stood only seconds before. Even the birds had stopped singing, but the smiling young man was nowhere to be seen

Chapter One

“Now, are you sure you want to go alone, Abigail?” Mother asked yet again as she frantically packed enough sandwiches to keep me fed for a week. I had given up telling her it was only three days.

“Yes, Mum.” I had begun to use every variation I could think of, sick of repeating that short answer. ‘Of course, Mother.’ ‘Definitely, Mummy.’ ‘Indeed, female parent.’ ‘Agreed, Mamma,’ and the Welsh version, ‘Ydy, Mam.’

All the versions were completely lost on her regardless of what I said; she was in her own little world of worry as usual.

“What did you say, dear?” I grinned and hugged her quickly.

“Oh, my dear sweet Mamma! What would I do without you?”

I saw the tell-tale blush on her cheeks. I had pleased her, and I liked that. Since Dad’s death two years ago from a fatal heart attack, she had become a hermit, barely leaving the house. Refusing to see any of her old friends, she spent her days cleaning and changing the furniture around. It had taken my brother, Ben and I eight months to pull her out of her black pit. We found a wonderful charity that helped her over the next three months with counselling and that helped Mum pull herself out the rest of the way. Her friends returned and now she had a busy social life again, but we still had an overbearing worry monster who’d fret about anything and everything we did.

She worried the most over my younger brother. A nineteen-year-old student taking whatever course he could get onto, as long as it was as far away from home as possible. As it happened, the only university to take him was in Lancashire. Not enough mileage in his opinion, but to Mum it might as well have been another country instead of a two-hour drive.

I, on the other hand, was a young woman open to anything as I waited for my life to begin. At twenty-four, I had jumped from one job to another, never staying longer than a couple of months as hope soon turned to dismay and boredom. Shop assistant, support worker in a residential home for the elderly, home help for the disabled, working in a garage as a receptionist, unemployed, and then finally a friend of my mother’s offered me a temporary job as an assistant in a primary school. It was there that I found my talent, not for looking after the children, though that had been pleasant if not hard work, but as an artist.

I had drawn as a young child, pencil drawings and watercolours mostly, but by my late teenage years, I stopped, preferring the multitude of music that annoyed my parents and all the clothing trends that went with them. Backcombed hair and wild makeup came first, followed quickly by outrageous clothes that showed a little too much flesh as far as my dad was concerned! Once I’d exasperated them with that fashion, I moved onto the ‘Goth’ scene, giving all my coloured clothes to charity shops and swapping them for black. My hair, my nails, my lips, my eyes, even my underwear was black— except for one dark purple Basque with frills. It still surprised me that my parents let me leave the house. They drew the line at bringing the dark side into their home though. Posters considered too evil were taken down when I was out, and arrays of male Dracula wannabes were turned away from their door.

Those years of striving to find my identity had been ‘fun’, but I always knew it couldn’t last and the ‘faze of doom’ as my mum called it, worked out of my system by the time I was twenty. I still preferred clothes that were just a little unusual, like black leggings with a frilly dress, or what I wore today, pale blue jeans with a multi-coloured jumper that reached past my backside and ‘purple Doc Marten’ boots to finish the ensemble. My shoulder length hair was a warm red and my makeup of choice these days consisted of grey/black eyeliner and a pale pink lip gloss. At the moment, I had my hair plaited for the long drive ahead of me, the eyeliner forgotten in my excitement.

For the last four months, I had been working part-time in an art shop. Following my revelation at the primary school, I’d been lucky enough to meet Shirley, a lovely lady who was embarking on an adventure starting her own business. She’d taken me on a temporary basis, but so far we’d got on really well. I enjoyed selling the paints and the pencils, the paper and all the utensils an artist might need to create their masterpieces. Shirley was an amateur painter herself, and she frequently exhibited works of art from local artists in her window and a small gallery in the back. Last month I had finally plucked up the courage to show her two of my pieces and she’d displayed them with a smile. The smile had turned to disbelief when both were bought within days of each other.

Yesterday, Shirley asked me to paint more for an evening she was planning and the theme was the coming spring. I’d never painted anything for a deadline before and panicked, shaking my head with determination as I’d made us both a cup of tea during a quiet moment. Shirley smiled that knowing smile of hers on hearing my myriad of reason not to do it, couldn’t do it, and pulled out a chair, sitting me firmly on it. “You have some holidays to take, you could take them now.”

“But I don’t know what to paint….” Even to my ears my voice sounded pathetic, and I cringed.

“Oh, I’m sure you’ll find some inspiration, you’re an artist. Perhaps that lovely Welsh village you’ve told me so much about? You can go tomorrow. I’ll manage till Tuesday.”

And that had been that. She helped me choose some paints and gave me a couple of new paintbrushes and canvas before pushing me out of the door. “Bring me back a masterpiece!” she called with a wave, and I’d been left standing dazed on the pavement followed by a tingling sense of adventure. I had four days leave; Shirley was right, I knew exactly where I had to go.

“Do you have the keys, love?” Mum’s voice interrupted my thoughts.

I nodded and kept my eyes on the large bag of food, blinking in a vain attempt to hold back the floodgates. She came up behind me and hugged me hard. Tears burned, and I sniffed loudly, trying to stem them.

“It’s alright, love, you let them come.”

“But why, Mum? It’s been four years since Nan ... and then Dad….”

“It’s about time you went. It needs sorting, and it’s your responsibility anyway. Gareth does hate renting it out to the English!”

I heard the smile in her voice and looked up. “Yeah, I know, but it’s hard.”

“Your Nan loved you dearly. It was only right that she left you her cottage, your favourite place in the whole world as I recall. Don’t you remember? I used to wonder what it was that you loved so much. Oh, I know you loved Nan,” she quickly added, seeing that I was about to defend her memory, “but there was something else about the place that sent you scurrying back there every year without fail, even when you looked like the devil’s brood!”

We laughed together. “I think Nan found me very amusing during those years. The locals certainly thought me hilarious.”

Mum smiled. “I bet they did. Doubt they had anything like you in deepest Wales with your black hair and black leather pants! What a sight!”

We finished packing away the huge flask of coffee and I carried the bag out to the car. My small overnight case was already in the back seat with a sleeping bag, pillow, a bottle of red wine and my handbag. I had already carefully packed the two canvases, my large sketchpad, my pencils, paints, and iPod, my essentials, in the car’s boot. “Okay, Mum, I’ll see you Monday afternoon.”

“You be careful, it’s been snowing down there. The heater should still have enough gas, but the local shop—”

“Mum!” I gave her a quick hug to stop her fretting. “I know where everything is. I’m sure it’ll be fine. Gareth knows I’m coming. He’ll have checked everything and put the heating on by now to warm up the place.”

Mum nodded and smiled. “Of course he will. I’ll see you on Monday then.

I glanced at my watch as I started the car. Friday rush hour had finished; I would enjoy a nice leisurely drive down. It would take roughly two hours to reach the small, picturesque village in the heart of North Wales, depending on how fast I drove. I put a C.D. into the machine and I was away with a backward wave at my mum before I changed my mind.

I had not been back to the cottage since Nan’s funeral four years and three days ago. She died peacefully in her sleep at aged eighty-eight and was buried alongside my granddad in the local churchyard. The small village church of St Mary had been full to the brim with people standing outside to pay their respects to a kindly woman who had lived in the village her whole life.

Not one person, young or old, had had a nasty word to say about Nan. She’d been a forthright woman who spoke her mind, plain and simple, and she fought for the rights of local people, voicing her opinion openly when big businesses wanted to change their way of life. Beddgelert had endured many hardships, but through them all, Nan had been there, and it seemed that she’d been appreciated, judging from the amount of mourners.

Many families had come forward to share their stories about how Nan helped them. When they struggled through lack of work or illness, and benefits had fallen short, they would often find a bag full of clothes and a box of food with one of my Nan’s legendary cakes or pies in them.

My dad had listened politely, but he wasn’t interested. He’d left the village when he was seventeen after finding work elsewhere and rarely returned to his childhood home. His father had died when my dad was only six years old. A fire had broken out at the farm where he worked and Grandad Huw rushed in to save the young mother. He’d failed, and both died. Nan shared so many stories about Grandad Huw. She was so proud of him and missed him terribly. I’d known him better than my dad ever would and I knew that saddened Nan very much.

As soon as Nan’s funeral was over, Dad had wanted to sell the cottage, but the solicitors shocked us both. She’d left it to me. He’d been furious, but I was twenty years old and legally competent and he couldn’t do anything about it. I tried to talk to him on numerous occasions about doing it up and renting it out, but he flatly refused to discuss it and died an angry and bitter man two years later.