Making Straight the Way

Helplessness on the hill. Even brother Ed, blind as a mole, caught those dark clouds clean, as he danced in a flustered trot across the wet banks of a peat black stream. We were too close to the car doors to call it an adventure, that said, my first experience, of wilderness wandering, came in with a cloud of midges. I can picture it to this day, running alongside my old man and brothers, trying desperately to escape across a plane of what we called ‘moon grass.’ Laughing hard and laughing cruel when a party member lost their footing and tripped. ‘Maintain your balance,’ the cry, a double-barrelled punchline, second shot of laughter to drop when the next victim took their fast-approaching fall. It was midday when the wind stopped blowing and our buckets were still empty of fish. Out from the reeds rose thousands of ravenous mouths. The glen was alive, and we were on the lunch menu, cursing and thrashing erratic tracks back down the valley and up the hill to our car. It was with wet feet and empty bellies we bid our retreat, skin itching and heads down, felled by the mighty midge.

‘You broke your fishing rod,’ said the first brother smiling cruelly.

‘You left our picnic on the riverbank,’ replied the second.

‘And none of us caught a fish,’ added the third, as all eyes looked desperately to Dad, who was padding his hollow pockets in the ongoing search for car keys.

The wilderness is a place where humanity gets tested. There is a deep silence to history’s most jaw-dropping walks, no murmurs of discussion, no opinions, no shouts of pride, no boasts and no slander, our voices hushed, so fragile the breath of life in such a place we stop and listen. Thankfully the midge story will do, we don’t all have to become characters in Touching the Void, or punters on Ernest’s trip south, we shan’t be joining Captain Bligh across the South Pacific, or escape imprisonment and sail up an uncharted coast with convict Mary Bryant. In a strange way these awesome endeavours have given us a glimpse of something much bigger. Their pages have ploughed pathways across the far reaches of our planet, not for us to travel down necessarily, but so that light can run in and hit home soil. We can part the curtains, open the door, take out a pot of steaming coffee and witness the miraculous beneath our very nose, flowers blooming and life growing, right up through the cracks in our garden paving.

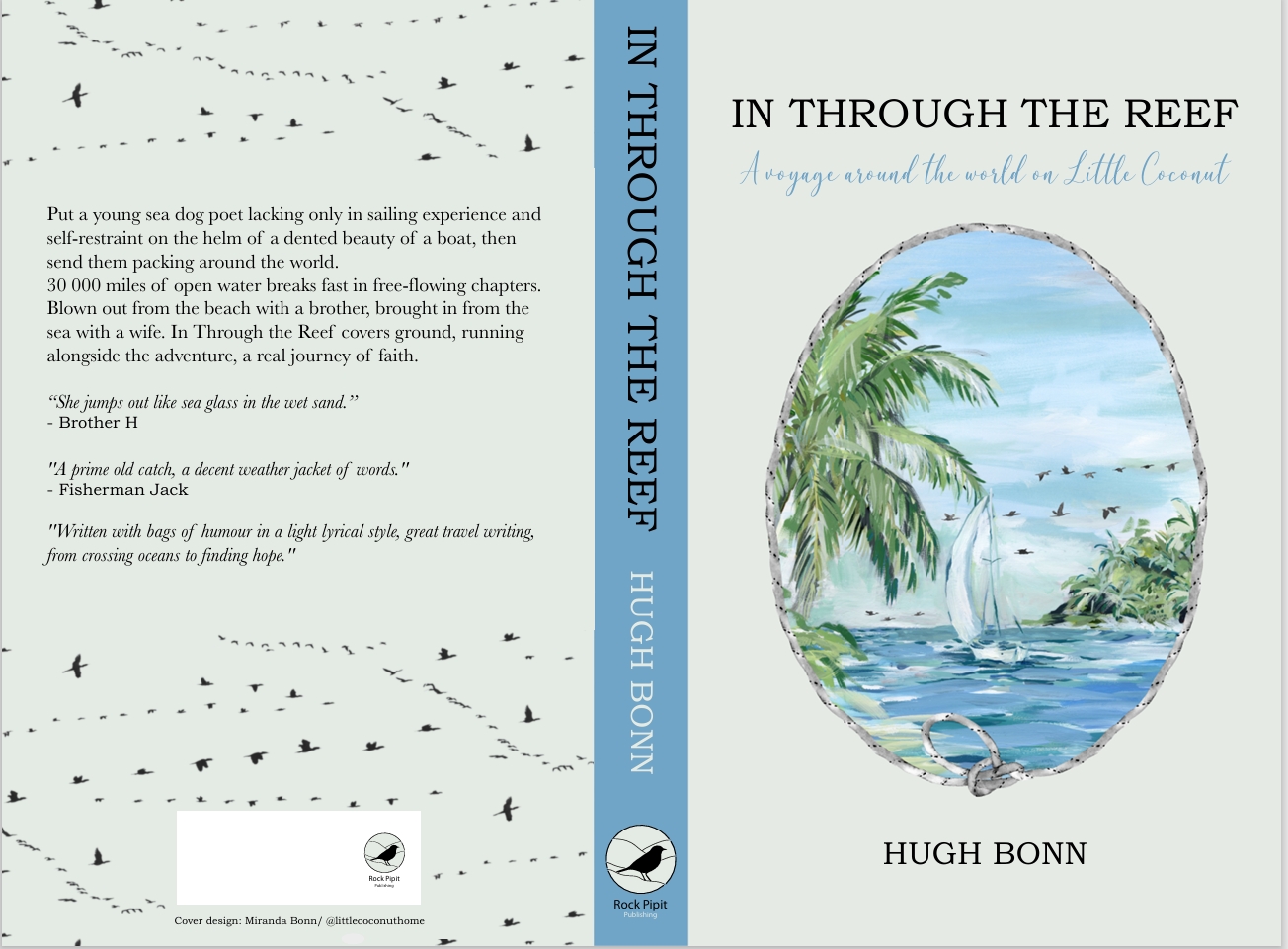

There was a man called John the Baptist whose life in the wilderness sums up what I’m trying to say. No doubt everyone has heard of him, the man who baptized Jesus. John understood the nature of light, the need of a straight line for it to travel far, he also understood the Fall, and his place on Earth connecting what lay beyond it to the villages within its walls. His life was a corridor for light. With this in mind, I attempt to write this book, not as one of those ground-breaking adventurers and not as someone who went out so that light could come back in, but simply as a witness to the gift that was my voyage around the world on a small budget cruising yacht called the Little Coconut.

Upon a bed of broken shells, the hermit crabs find their shelter, part opportunist, part beggar, one claw to barter and one to borrow, arms like merchants, legs like thieves! The crabs congregate, in small gatherings, in quiet huddles, heads all turned in from the happenings of the beach. Small islands in the sand, islands unto themselves. They meet to find a better fit, the shell to a hermit crab is the cornerstone of a happy life on the seashore.

These shells come not from the crab of course, but instead from the mollusc, an inhabitant long dead, who out of invisible elements in the sea somehow produce their bricks and mortar, who whilst chilling on the seabed, build a house. No blue language bouncing off the rocks down there, no pointed fingers, no heavy machinery, no rowdy gangs of block layers and no project managers shouting down the phone, they simply breathe and construction begins. This house blends in perfectly with the natural environment, it is light and strong, the curves are flawless, the internal walls finished with mother of pearl, they can withstand punishing waves and long stretches of water, they wash up years after the mollusc has gone, providing new shelter for a totally different inhabitant. With intricate patterns, with fans and spires, with colour and precision, the shell is formed, a truly awesome creation.

Our journey began with a scuttle across the sand. We were naked and in search of shelter. We were of the crab of course, and not of the mollusc. Twelve tons of steel floating effortlessly on the drink like a duck’s feather, we knew nothing about the boat, we did not arrive by way of water. All Walt, my Cornish friend, could do was kick the hull and cry ‘Solid boat.’ All Brother H and I did in reply was nod our heads and climb aboard. Looking back into the life of John Hanna, the man who designed the blue print for Little Coconut, I see a different breed of sailor, a true sailor, one who took no short cuts, who had life tough, who meditated on laws both unseen and seen. A man who lived for much of his life beneath the waves. Struck down by a torrent of scarlet fever as a child he just survived, rising from that bed of sickness deaf as a post, to be felled not long after by a passing trolley in Galveston Texas, his right foot, severed at the ankle. Nothing could stop John Hanna, everything handed down fed into his passion for design, even the bad times and the hard times helped forge his legacy of seaworthy boats. His life was a testament to that unstoppable formula of character first and talent second. A combination you can feed with heavy rocks of suffering and get in return unsinkable hulls, hulls that sail off in distant winds, through the fog of time, into the depths of generations not yet born.

If we’d been born back then, in around 1900, if we had lived down by the sea in Dunedin Florida, we’d have witnessed John Hanna at work, making straight our paths across the water. It was a time when small boat cruising had only just become possible. By cruising I mean passage-making for pleasure, which I realize seems a slightly extravagant word for what is essentially getting rolled round in a can for some weeks. The cruising community had begun its assembly, lining up in various harbours around the world. Back then boat building in the leisure sector wasn’t the mountainous landscape it is today, full of tall trees and thick shadow, it was a flattish plane of many shy hills, even the moles were making a difference. Every harbour had a tradesman capable of knocking something together and every town had a designer hoisting high a set of plans in the hope of attracting a would-be adventurer. The doors were open, so to speak; Tahiti and back again was a reality, not just for the merchants and the whalers with their crews of hardened vagabonds, but this time for the amateur adventurer. It was in this rich vein of discovery and optimism, a vein bound so closely to those unbreakable laws etched beneath the seams of this world, that gave the direction required to put any old Tom, Dick and Harry on the water, and get them in, 9 times out of 10, on the other side. Designers like John Hanna, they blew out boats like bubbles, catching the light, prompting a new generation of Noahs to make true their arks, grab the wife and kids, round up the family cat, throw in a sack of potatoes and head off into the flood.

Beneath a blanket of stars and stripes, the Tahitian ketch broke surface. America at that time was isolationist, she sat off to one side of the word stage, bolstered by a constant flow of migrants flooding in. With regard to boat design, Europe’s old apple cores got a new lease of life. John took the lines of a Greek sponge fishing boat, a hull from the Mediterranean of all places, with that rich history of boat building spanning back thousands of years, modifying certain characteristics for offshore use. The blueprint for his Tahitian ketch sat dormant for a decade or so, it took a pretty major shakeup for America’s boating population to take notice. The great depression threw out its fists of winter in 1930. A few years later when the hardship subsided his ketch started to attract some attention. With a name like Tahiti, she had that exotic lure. Hanna was calling on a Polynesian paradise when he used that name, Mutiny on the Bounty all over again, minus the bloodshed and plus the chance of making it back. By 1935 the blueprint was selling at last. Designed at 30 feet, this was a boat tailored for everyday adventurers, not for big budget professional endeavours but for flash in the pan hacks.

John Hanna managed something pretty momentous when he published those plans. One hundred years on and his boats are still doing laps of the planet. In November 2017 aboard Little Coconut, Miranda my wife and I made it in to Australia, seven years after I left with Brother H. At the finish line we were greeted like true hermits, no red carpet or Hollywood smile. The woman at the marina we had entered looked like she’d spent the duration of my circumnavigation sucking on a lemon. ‘Bum’s Bay is around the corner, you have no insurance, please leave our pontoon as soon as you've cleared in.’ That was our greeting, Miranda was refused a shower, after crossing the Pacific Ocean without running water, a working toilet or a fridge, washing in one bucket, answering nature’s call in another, for over a year, you couldn’t write it, but that was the purpose of Hanna’s design, our trip was a testimony to its success. If boats ever needed bumper stickers, Little Coconut’s would read, ‘Carrying bums around the world since 1923.’ The thorny reception we got in that flash marina crowned our trip, it crowned the tale of this remarkable little cruising boat and its ability to take sailors with little experience across the sea and back again.

A Shell Made Ready

The beginning, that wake-up call, it wasn’t quite the same as those seafarers of old. I wasn’t clubbed on the back of the head and dragged off to sea, waking to the smell of salt and the bosun’s angry whistle. The stream that carried us down had a much kinder hand. Like all salt-worthy sailors one must accept the reality of becoming a leaf, cut from the tree and blown into the river, taken down to the sea. Our journey to the water’s edge was different in that it was privileged, there were no rocks or rapids, no whirlpools, no snapping turtles or hungry fish, we made it into Little Coconut with fat bellies and soft hands.

Thankfully I wasn’t alone, Brother H heard the call of the wild too, putting a mule’s hoof on his job, all in the space of a few months. By June 2011 Harry aged 24 was free from his employment in Hong Kong working on a rail tunnel, and I aged 26 had escaped the mines. It was a side scuttle across the sand for H and I, finding adventure in a washed-up boat called Little Coconut. In the meeting of these three streams new life began, just before the sand soaked away our dash, just before the boat hit that scrapyard back eddy, the timing was perfect, we joined paths to make that last push together, trickling out quietly into the crashing waves.

The day we found Little Coconut stands in front of all the other days spent working underground in Australia, hundreds of twelve-hour shifts sit behind, indistinguishable like drops of rain in a grey cloud. I felt guilty driving past the construction sites in the middle of the week, I’d somehow been released, it was all suddenly outside Walt’s car window, flashing by on the roadside, slowly dropping away into the wing mirror, a blur of dust and high vis jackets. We crossed the Gateway bridge heading for the first harbour available, pangs of guilt gave way to a burst of excitement, out in the distance a sea of blue awaited, an oblivion of sparkling water.

The harbour we found ourselves walking along was Manly in Queensland, just outside Brisbane, a quiet village at the bottom of a shy hill, peaking out across a sheltered bay from between the mangroves. Manly’s yacht basin manmade, the shallow mud banks dug away, a channel dredged and walls dropped in, home to an armada of leisure, cruising yachts and private fishing vessels, house boats and racers, day sailors and dinghies. Brisbane the city over the hill, Manly, a quiet retreat, a place where sailors spring out from at the end of their working week.

It was an abstract image of adventure which brought us to Manly, a cloudy vision more than anything else, so void of definition and so full of colour, one couldn’t see the break between land and sea. Harry was across the water in Hong Kong finishing up work, it was my job to find us a boat. Our brief, something to sail home on, the money, five grand English a piece. Pretty clear instructions on the computer screen, a tad hard to get one’s head around in reality. It was with glazed eyes our trip wallowed, unidentifiable like an amphibian in the mud. Walt and I rocked down to the harbour as one might to a Saturday morning car boot sale, there was no effort required, we bought coffee, we walked the sidewalk, and we shot the breeze. A telephone conversation about a possible boat in Manly had fallen through, we drove down anyway, it was all theoretical at this point, a flat featureless plane. Walt stopped at a sidewalk billboard; the advert read ‘Budget cruiser.’ ‘No way, that boat is right here,’ said Walt, pointing to the words Manly, he then read out ‘East Coast marina.’ Pausing for a second before adding ‘This is East Coast marina.’ I looked up, the sidewalk had vanished, it had given way to a marina carpark, we’d walked right into the lion’s mouth.

Sitting on Little Coconut was as good as coming to, the salesman didn’t have to say anything and I didn’t have to ask anything, I didn’t need the specs, or the dims, or the boat history, it was all laid bare before us. If you imagine an infant, an infant without yet the words to speak, who sits there in the sun and cries out for an apple, cursing with splutters and shouting in babble. It is of that moment, when the child’s thirst is quenched, I speak. When the vision suddenly gains focus and the taste of an orchard is delivered to the lips. That was what it felt like sitting on Little Coconut. One man’s junk is another man’s treasure. The sun was falling hard and hot, my T-shirt damp with sweat, Walt had his head back and feet up by the wheel, a Cornishman whose only link to boats being his Dad, who once worked on a trawler out of Newlyn. ‘This is it,’ Walt said, ‘You boys are off! H is going to love it.’ And with that, in a simple twist of fate our journey began.

To layout a picture of Little Coconut she is about 30-foot-long with an extra four-foot bowsprit. Her cockpit non-existent, instead she had a high-sitting flush deck, her wheel was bolted straight on and set up with a lock and pinion steering device. Her stern was shaped like a canoe with a heavy-set cast-iron rudder hung on three fist-sized hinges. She had a full keel, a cutter rig and a huge genoa, her mast thick like a tree trunk. There was no furler up front, the sails all hanked with free running halyards cleated to the mast. The rigging was high quality with strong fixings to the deck. Below she had a cave for a cabin, walls of bare steel accompanied by primitive carpentry. Each bunk distinct in appearance, each bunk displaying a different epoch of human development, from prehistoric lashing to rusty iron nails clubbed down into splintered planks. The wood part foraged between the tides, part begged for at the scrap heap and part no doubt borrowed from various building sites around the globe, an eclectic mix of varied hues. My favourite piece, which represented the best of Little Coconut’s seven wonders, the engine box, a complex entanglement of different wood types, a jigsaw of many parts, each differing in length, breadth and thickness. The structure, having scaled all three of the physical dimensions reached out for a fourth, with a spiritual element definitely present. The practice of engine maintenance, a mini pilgrimage aboard Little Coconut. Having been locked in an awkward pose, having dropped the spanner into the bilges and lost the screws, drenched in sweat and oil, it was the reassembly that had the potential to make you crack. The only way to avoid ‘frog in the sock’ syndrome was slow meditative breaths and calculated steps.

There was no plumbing on the boat in the conventional sense, no toilet, no water tanks, no shower and no taps. In terms of millennial technology Coconut had resisted all temptation, there was not so much as a chart plotter. The galley no better and arguably even worse, missing the whole concept altogether, Little Coconut had no fridge and no cooker. Her engine definitely represented another boat wonder, how vividly I remember my dad flying over to visit before we left, the gravity of this misunderstood beast was overwhelming. Dad opened the box and peered down, an ink-stained octopus draped in shadow gazed back, sitting in a sewer of black sludge. It was too much to handle, out of his pocket came not the sailor’s trusty Leatherman but instead a bottle of Holy water, he doused the engine generously before closing the box for good, checks not necessary and blessing complete.

All the wonders and missing teeth aside, all cladding forgotten and garnishes dropped, Coconut was the real deal, a war horse, a working mule, a sure thing, a good sort. She had integrity, personality, grit and class, she was strong like a bull, she was uncomplicated, forgiving and brave, all the things you want in a boat lost 1,000 miles from anywhere, caught three days into a blinding north Atlantic gale. Dad flying over and blessing the boat was his way of letting go, surrendering his job as an Earthly father to our Heavenly one, it was out of his hands, Holy water on a rusty old tractor engine, what better symbol of human surrender is there under the sun?

Once we got the boat, everything fell into place pretty quickly. In Queensland the best cruising season is June, July and August, the winter months. Our purchase came through around April sometime, which was perfect. I had eight weeks to get her ready. Jamie, a friend from Jersey, was flying over to try his hand at sailing which meant we were a crew of three, our start date early June. During those eight weeks I was working nine days on five days off, a FIFO (fly in and out) gig at Broken hill a small mining town in outback New South Wales. That brief chapter between buying Little Coconut and leaving was pretty crazy. I was flying one thousand miles, dropping down to the bottom of a busy and complex underground mine, then flying back and working on the boat. I’d somehow got myself superglued to a yoyo, I was dunked, in and out of the darkness, up and down from earth to sky. It was mine, clouds, boat, then clouds, mine, clouds, boat, my head was spinning, those dark lonesome tunnels turned and twisted, hundreds of miles worth, spinning in infinity, I was praying for it all to end. I managed to get a chart plotter fitted, I antifouled the bottom and changed the anodes, I organized some new sails, brought an offshore life raft and some life jackets, I repainted the inside and changed the engine filters. We were ready for the off, those old oak doors had creaked open, and with that came the first notes of spring.

There really aren’t that many routes around the world under sail, not for us budget cruisers anyway. Some passages may be harder than others to find, some may be wide, and others narrow, certain roads not for the faint-hearted, but there aren’t many. It is no wonder we find ourselves walking a path of footsteps, of rounded stones and charred ground. It is no wonder we often retrace our steps to find the right road. Sailors don’t make up routes around the world, they follow them, written into the makeup of this planet like a fingerprint.

Planet Earth has an uneven distribution of heat from the sun. If Earth was big George Foreman’s punch bag, and if his fists were light, that mid-section of the bag, the area permanently indented like a fat man’s couch, that would be the Equator, soaking up all the heat. At either end of the punch bag, above the big guy’s straight and below his rib shot, sit the poles, regions where rays of light hit at an angle and reflect back off into the atmosphere. These polar regions are areas of high pressure due to the cold sinking air, that belt round the middle is a band of low pressure where the air gets hot and rises. This is the main engine behind our weather. A pressure gradient is formed, this gradient produces two additional belts in each hemisphere, as the cold air runs off down the latitudes it heats up, rising to form a sub-polar low. In turn, as hot air is drawn away from the Equator it cools, sinking to form the horse latitudes, a sub-tropical high.

This set up is genius for a sailor, you get two directions of travel in each hemisphere, the wind always moves from high to low and it can only move right because of the Earth’s spin, sub-polar low to sub-tropical high equals westerlies, Equator to sub-tropical high equals easterlies. Two highways etched into each hemisphere, one road heading out full of dreams and one road heading in full of stories. The planet is unlocked in this way, through a series of corridors. Sitting on the Cornish coast copping a prevailing southwester right on the nut one might think it impossible to reach America under sail; not so, all the boat need do is head south till the butter melts, catch hold of that trade, then head off with the setting sun. Now it gets a little more complicated with the doldrums mixing up life in the middle, tropical storms affecting the trade wind belts and the adverse effect of large land masses. The other area which might shake up one’s sailing route, once the physical possibilities of actually making the trip have been addressed, is the whole human aspect. When you rock in after a month at sea, your boat hasn't changed, it is still your home, the water is still water, the weeks have ticked by, all of a sudden you're facing a shoreline 3,000 miles away from where you started, debating what the crack is ashore. Is that crazy one-eyed fisherman trying to rob us or does he just want a bottle of Jack Daniels?

For us, given our levels of inexperience, we thought a trip up the east coast was the way to go, Brisbane to Darwin over the winter months, a great shake down leg. The cyclone season in the Indian Ocean runs from November through to March, so if we left Darwin in August, with a view to getting out of the Mauritius area sometime within the month of October, it made a summer in South Africa possible, Cape Town for New Year. This rough outline was in the back of my mind, but we didn’t talk about it much, getting our mini battleship out of a packed harbour was number one priority, by June 1st Little Coconut hadn’t yet left Morton Bay.

Comments

This excerpt begs the…

This excerpt begs the question: what is a memoir? Well, let's start with what it isn't (or shouldn't be). A good memoir is not the telling of a true story; it's showing it. It's about (excuse the pun) bringing the reader on board so we can re-live the unique experience that has driven him/her to commit to paper. 'In Through the Reef' goes several steps beyond that, not just in the recording of an extraordinary event but in how the language and style combine to bring it to life by delighting the senses and rubbing our noses in the sights, the sounds and the smells of the natural world. Excellent writing!

A compelling start. It's…

A compelling start. It's slow-paced yet deeply immersive. A brilliantly written piece.

Despite some grammatical…

Despite some grammatical problems, it pulled me in as a reader. A good edit would help, though.