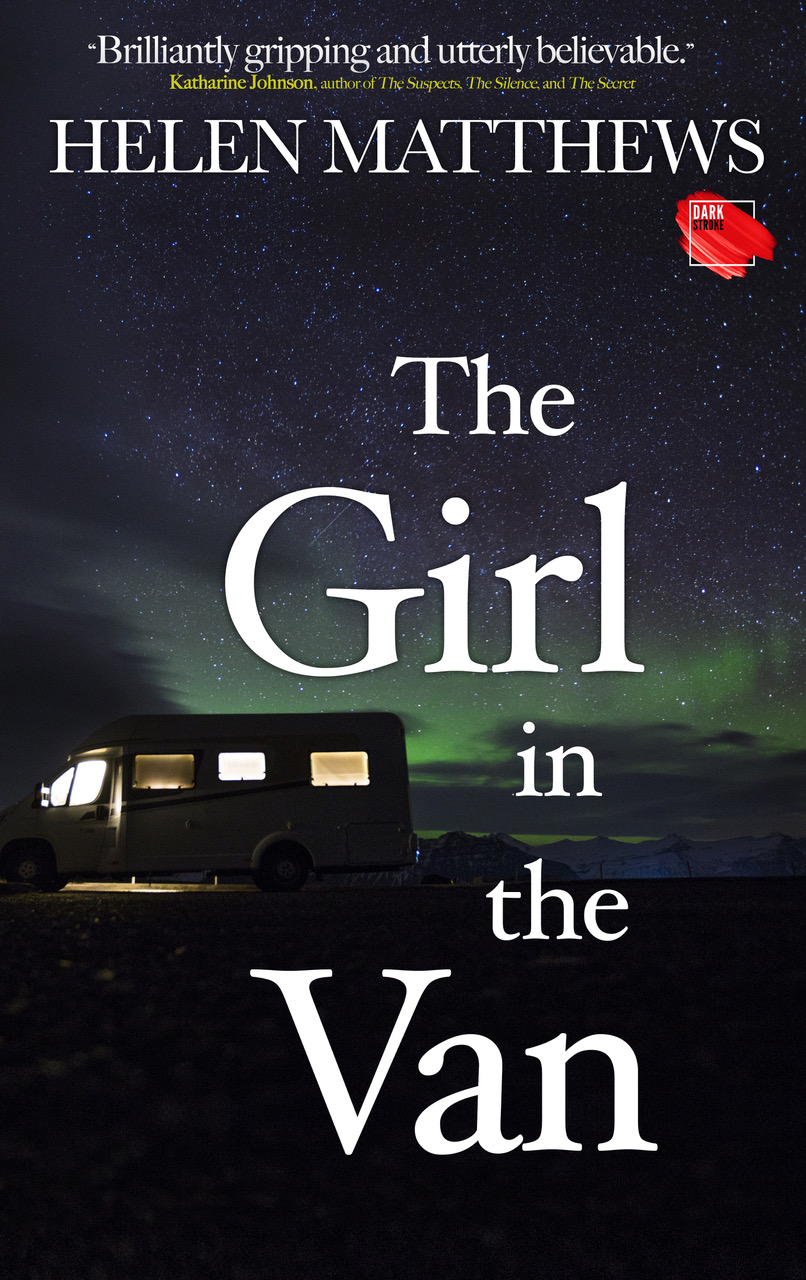

The Girl in the Van

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

The Girl in the Van

Chapter 1

Present Day - Saturday

Laura

I’m running away again – from life; from other people. Let them think what they want. Why should I explain myself?

My heart is thumping, and my right arm feels leaden from waving goodbye to my new ‘friends’ who have broken off from preparing the communal supper. Emily is gripping a knife in one hand and a tea towel in the other; Bill’s gulping beer straight from the bottle and staring at me, baffled. No one is smiling. Today the sun finally came out, so they can’t understand why I’m leaving our singles group holiday on this peaceful West Wales campsite where I’ve paid for three more nights.

I wind up my window, ram the stiff gear lever into reverse, and edge my ancient (but new to me) campervan off its grassy pitch. The van and I aren’t yet working as a team, and I’m worried my wing mirrors might not pick up any tiny tots scampering from the playground, following the smell of caramelising meat back to their family’s barbeque. It’s early July, not yet school holidays, so the only youngsters are under-fours and teenagers who’ve finished their exams. My t-shirt is damp with sweat, and my foot is shaking as I drive cautiously down the track towards the main exit.

The people I’ve met on this holiday are harmless. Especially Bill, who seems an okay sort of bloke. He’s a fraction the wrong side of forty, like me, but his habit of separating me from the others and starting deep, meaningful conversations has been unnerving. I don’t do deep or meaningful. I rarely do conversation. Superficiality and the thinnest veneer of what passes for company suit me fine.

This was my first campervan trip, and it took me half hour to disconnect the water and gas bottles, unplug from the power supply and trek to the communal bins to dump my rubbish. I’d planned to flee and text the others when I was on the road, but Amy guessed my plan and assembled this farewell party to wave me off, promising they’d see me again soon. I don’t think so.

My vehicle crunches over gravel as I reach the gatehouse and pull into the parking bay opposite the campsite office to tell Dave, the manager, I’m off.

“Sorry to see you go, Laura.”

“Bush telegraph?”

“That’s right.” He raises his clipboard and gestures at the main gate. “See that queue?”

I glance towards the road. I’ve forgotten it’s Saturday, so this must be peak arrival time for holidaymakers. Cars towing caravans, engines idling, are queuing to enter the site. “Yes.”

“Blasted barrier’s playing up. I’ll need to raise it by hand for each arrival and queue them in this parking bay. Could you move on?”

“Okay. Sure.”

“Sorry.” He gives a wry grin.

I restart my engine and swivel round for one final check on my living quarters. The bed fills the whole space. I’ve left it assembled and covered with cushions, but my backpack has burst open, spewing out clothes and shoes in haphazard heaps so it looks a bit like Tracey Emin’s Unmade Bed artwork. I notice a lump in the duvet – odd; I don’t remember stuffing pillows underneath.

A car beeps its horn. Dave raises the barrier, holds it aloft and motions me out. Cars rev their engines, and it’s hard to edge past along the narrow country lane. I glance in my mirror. That bump under the duvet is rippling gently, out of step with the motion of the van. It must be an illusion. Like that fleeting sense of movement you get when you’re staring out of the window of a stationary train and the one on the next platform pulls out. All the same it’s unsettling, but I can’t stop to check because the winding road has deep gulleys, hewn from rock, running along both sides and there are no passing places. I need my eyes on the road and hands clamped onto the steering wheel.

Seeing that bump has spooked me. What if one of the kids from the campsite climbed into my campervan while I was packing up and getting rid of my rubbish? Perhaps they were playing Hide and Seek. The last thing I need is to turn around and drive back to reunite a missing child with their angry parents. But if it is a child, wouldn’t they have realised we’re on the move and crawled out of their hiding place?

“Who’s there?” I ask in a hoarse whisper, glancing in my rear-view mirror.

Silence, apart from the thudding of my heart. Perhaps they’re scared.

“You can come out. I won’t be cross.”

No reply.

I’m itching to check, but tall beech trees leaning across to embrace their neighbours on the opposite side of the road form a dense tunnel and block out light. The road is empty.

I grit my teeth. I won’t panic. I’ll find somewhere to stop and sort this out.

At last a sign for a picnic area comes into view and I reach a clearing in the trees, with wooden tables dotted around on scrubby grass. A Land Rover is parked in the layby, but no sign of a driver. I ease my van to a halt, wrench on the heavy handbrake, unfasten my seat belt and clamber through the gap next to the driver’s seat into my living quarters.

“Whoever you are, get out now.” I shove pillows and cushions aside to reveal a mound under the covers. My hand is trembling, and I can’t bring myself to touch it. What if it’s an injured animal? A horrific image of the decapitated horse’s head under the bedclothes in The Godfather slips into my mind. Breathing rapidly, I grasp the duvet in both hands and tug. It seems to be tucked in or weighted down. As I slide my hand down the side of the mattress to free it, a skinny arm thrusts out from under the heap of covers.

I freeze. “What the heck!”

The arm is wearing a friendship bracelet and holding up a note as if it’s a white flag. Shock forces me to lean in and squint at the scrawled words: Help me. Don’t tell anyone.

A laugh that’s part-hysteria, part-terror catches in my throat as I yank back the duvet and uncover a girl with tangled dark-blonde hair and a nasty gash on one side of her face. She cowers away from me, covering her face with her hands.

“Sit up,” I demand, grabbing her arm. She’s a teenager, not a small child, and she’s wearing a white t-shirt with a faded photo of a band I don’t recognise. “What the hell are you playing at?”

The girl levers herself into a sitting position, keeping her face curtained by her long hair.

“Look at me,” I say, clamping my hand on her shoulder and turning her to face me.

She straightens her spine, rocks forward and flicks her hair back behind her shoulders so I have my first proper look at her face.

I gasp.

It’s her! Ellie.

For the briefest of moments, I allow myself to believe it.

Chapter 2

Thursday (two days earlier)

Laura

I’m driving west from London when the bridge across the River Severn, dividing England from Wales, looms into view. My heart lifts. After being uprooted, the pull of Wales is a visceral thing. There’s a name for it: hiraeth – a kind of call to your inner self from a half-forgotten place or time. I’m surprised it still has this power. When I fled Wales two years ago, I was desperate to escape everything from my old life.

The bridge is painted a pastel shade of green. When she was young, Ellie used to say It’s all minty. Today the spearmint hue chokes me with memories. I’m making a detour and visiting my mother in Cardiff. None of what’s happened is Mum’s fault, but she blames herself because it happened on her birthday. She’d love to take away my anguish and carry the burden for me, but she can’t do that. No one can.

I’ve been driving for three hours, rarely accelerating above sixty. The campervan’s controls are heavy, and a vibration from the transmission shoots pins and needles through my right leg. At the junction for north Cardiff, I signal to leave the motorway and follow the winding road to the village-turned-suburb, nestled beneath the hills on the city’s northern fringe, where my mum still lives.

The driveway is empty, but that doesn’t mean she’s not home. Mum chooses small cars to fit inside her narrow garage, and cares for each one as if it was a pet or a child. If her car’s wet when she arrives home she dries it with a cloth first, before going indoors to change out of her own sodden coat and shoes.

I dawdle up the path to the oak front door, press the bell and wait, noticing the blinds are raised, the sun’s rays turning the front windows into a mirror. Mum answers the door wearing fluffy pink slippers and the apron she’s kept for baking since I was a child, but there’s no smell of baking in the house. Her newly-white hair shocks me, even more than the deeper frown lines etched onto her face, because Mum and her hairdresser always conspired to keep it chestnut brown. As she scans my face, her eyes mist with tears.

“Hello, Mum.” I bend forward and kiss her cheek.

She stares at me, this ghost on her doorstep. “Laura, sweetheart. Why didn’t you ring?” She rehearses a smile, but it doesn’t mask her sadness. And that’s understandable when you haven’t seen your only daughter for two years and she won’t tell you her phone number – or where she lives.

“If I’d known you were coming, I’d have…” Her voice trails off.

“It’s just a flying visit, Mum. I can’t stop long.” I could, of course. It would be easy to abandon my ridiculous holiday plans and stay all week.

She dabs her eyes with a corner of her apron.

“Can we go inside?” I place one foot on the step.

“Of course.” She opens the door wider and peers beyond me at the road. “Where’s your car?”

“I left it in the car park up at the Deri Inn.” If I’d parked my metallic red campervan outside, the curtain-twitchers would have worked out the visitor was me.

“Oh. I see,” she says in a flat voice. She leads me into the sitting room, motioning me towards the sofa as if I were a distant acquaintance. The grate is filled with a dried flower arrangement, which she’ll replace with logs in November, and the walls are still painted her favourite shade of China blue. Even on this summer’s day it feels chilly. The framed family photographs have disappeared from her mantelpiece. She must have packed them away. I can understand that.

We sit facing each other, and I cradle my small backpack on my lap and fiddle with the strap.

“Let’s have a proper look at you.” Her scrutiny makes me uneasy. “You’re so thin!”

She’s right. I’ve lost over a stone. The weight fell off without me noticing. I tell myself I’m happy with a trim waist and thighs that don’t bulge, but my jutting collarbone makes me look like I’ve an eating disorder. I do eat, but sometimes I forget. Most mornings I have cereal. If there’s no milk, I swallow it dry. In the atrium of my office building is a sandwich bar, where I buy lunch, but come the evening, I can’t be bothered. If I feel faint, I go to the fridge and throw together whatever I find into a makeshift meal. Perhaps scrambled egg, cheese and blueberries, with baked beans scooped cold from the can.

I left home this morning without having breakfast. A piece of cake would be nice, or even a biscuit, but Mum just stares at me so I get to my feet. “Let’s have a cup of tea. Stay there, Mum, I’ll make it.”

“Of course. Sorry.” She trails behind me like a puppy scared to let its master out of sight. Through the steam of the boiling kettle I see her shape her mouth to ask a question, but words take a while to come. Finally, she asks, “How’s your job?”

I shrug. “It pays the mortgage. I can’t ask more.”

She flinches, and I feel mean for blanking her effort at harmless small talk. It’s the same when I phone her – from the office, because I won’t give her my number; our conversations are full of silence and the sound of each other’s breathing. I make tea in the brown pot. Mum uses teabags now, so I don’t have to faff about with tea leaves and a strainer. In the usual cupboard, I find the barrel-shaped biscuit tin, with a fading picture of Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding. Mum always loved fairy-tale romances, and her marriage to Dad was happy, though he died when I was seventeen and she was barely fifty. She doesn’t get it when relationships turn sour.

The biscuit tin is empty, and that upsets me. She used to have friends round for coffee to put the world to rights and boast of their grandchildren’s achievements. But then, Mum couldn’t join in that conversation, could she?

While I was looking for biscuits, she’s poured our tea and taken it into the sitting room. She pulls out the hand-painted coffee table she made in one of her arts and crafts classes, and sets the mugs down on coasters. When she speaks, her tone is sharp.

“How much longer are you going to keep up this nonsense, Laura?”

“What nonsense?” I feign surprise.

“Hiding away. Not visiting.” She’s abandoned the effort to smile, and the corners of her mouth droop.

I shrug. “I’m waiting for things to calm down. If you hear anything, let me know.”

“Like what?” She bangs down her mug, and liquid slops onto the table.

“Like Gareth’s got a new girlfriend. That he’s getting married. That sort of thing.”

She gives a tight smile. “Can’t you forgive him? It’s been almost three years.”

“Neither of us can forgive, Mum.”

I don’t tell her I’m afraid of Gareth and his rages. I never told her the truth about what happened between us. She’d like nothing better than for him and me to get back together. That’s why I won’t tell her my London address. I know she still sees him, and I can’t trust her not to pass it on.

“So where are you heading?” she asks.

“It’s a sort-of holiday.” I choose my words carefully. “I’ve been working flat-out, so my boss told me to take some annual leave.” I don’t tell Mum that alarm bells go off inside an organisation if someone who deals with accounts never takes a holiday. They suspect you’re fiddling the books and siphoning off money into your own account. White-collar criminals cover their tracks by being diligent workaholics, and my work pattern ticked all those boxes. Our office’s barrier entry system records everyone’s arrival and departure times. My boss told me he’d been sent a report showing I was averaging seventy hours a week, hadn’t taken any leave for a year, and often went in on Saturdays. I’d have gone in on Sundays, too, if the building wasn’t closed. They’re calling in the auditors to investigate, my boss warned me with a nervous smile. It’s best you take some time off. To my mum, I say, “I guess they were worried I was working too hard.”

“I’m glad your company takes employees’ health seriously. Where are you off to? To visit old friends?”

I have no old friends. I left them behind in the chaos of fleeing my past, so I take a deep breath and tell her, “It’s a singles holiday on a campsite in Tenby.”

“But you don’t like camping.” Mum’s eyes widen in surprise. “You and Gareth always rented a cottage in France.”

“Something different will do me good.” My answer might sound flippant, but the decision was anything but. When I discovered the holiday was in Tenby, I almost cancelled. Could I face returning to Wales? But I realised it would give me a chance to see Mum and an excuse to make the visit fleeting. “I’ve bought a campervan,” I tell her.

“What?” Her jaw drops so her mouth hangs open.

“Don’t worry, Mum. It’s no bigger than the school minibus – I was trained to drive that, remember?” I don’t tell her tonight will be the first time I’ve slept in it. I show her a photo on my phone. She takes it from me, enlarges the picture and squints at it, staring hard for several minutes.

“I’m not keen on that bright red colour. And it’s ancient – the registration plate’s the same year as that old Astra I had – pre-Millennium. Are you sure it’s reliable?” She hands me back my phone.

“I’ve had it checked over by a mechanic. The engine’s fine.”

“I don’t like the idea of a singles holiday – you being all alone with a group of strangers.”

On the scale of bad things that have happened in my life, this barely registers. “A campsite’s a public place, Mum. Don’t worry.”

I excuse myself to use her bathroom. When I return, Mum’s sitting at her old bureau scribbling a note with her fountain pen. She doesn’t hear me entering the room and flinches, covering whatever she’s writing with her hand, then she slips something into an envelope and hands it to me.

“What’s this?”

“A small cheque towards your holiday.”

I hold up my hand. “Honestly, Mum, I can’t accept it. Spend it on yourself.”

“I have more than I need. It makes sense to pass some to you before I die. Who else is there, after all?”

“But you’re not old, Mum.”

“There’s nothing I want,” she says in a flat tone, and I feel a stab of guilt. Mum used to have a zest for life. When Dad died over twenty years ago she was still young, but she didn’t let it crush her. She was a senior librarian, and after she retired she went back to the local branch as a volunteer and worked for free because she was worried austerity cuts were impacting the library service. Later she trained as an advice counsellor and set up a branch of the Citizens Advice Bureau at the library.

“I feel weary,” she says, and I notice a greyish tinge to her skin and bruise-coloured circles under her eyes. “I hope I don’t have to go on for years.”

I stare down at the envelope. If it makes her happy to give me some money, I should accept it graciously. “Thank you.” I give her a quick hug.

“What campsite are you going to?”

“Sand Dunes in Tenby. Why d’you want to know?”

“I’ll look it up on the internet then I can imagine you there. Can you stay a little longer?”

I glance at my watch. It’s nearly four o’clock. “I suppose another thirty minutes.”

It seems her gift was a prelude to launching into the only topic she ever wants to discuss. She settles in the chair opposite me and leans forward, hands clasped.

“Gareth came to see me last week. He’s good at keeping in touch.”

My heart beats a little faster. “How was he?”

“Better, I think. He looked fitter at least; he’s been working out at the gym, and he went back to rugby coaching last season.”

“Good.” The last time I saw Gareth he was a flabby, emotional wreck, his face bloated from alcohol. When she mentions him in our phone calls, I switch off. Mum spent too long on Team Gareth. It felt like she was siding with him against me.

“Anyway, the rugby club’s been his saviour. He spends all his spare time up there, so he’s not cutting himself off from people any more.”

“Is he working?” I ask. Gareth’s a carpenter and had his own successful business building hand-crafted kitchens, but when I left he hadn’t had a commission for months and was sliding down the slope towards bankruptcy.

“Yes. He wound up his company. Now he works as a contractor for someone else, but he seems to have plenty of work. And he’s abandoned his mission to investigate – until he finds a new lead.”

“Mission! I’d call it an obsession.”

“Who can blame him?”

She’s right, of course. None of us knows how we’ll behave when the worst thing possible happens. My response was to shut down, stay numb and push everyone away. Gareth’s grief turned to rage – against the world, against himself, and ultimately against me. He lashed out at the way he was treated by the community and the press, and picked fights with anyone who asked questions or voiced an opinion. When some busybody organised a meeting about keeping children safe, he chucked a brick through the window of the church hall.

I get to my feet and collect up the mugs. I have a long drive ahead before I face a group of new people.

“Did you know,” Mum continues, unrelenting, “some of the teachers from your old school belong to the rugby club?”

“Sure, they always did.” What else can you do in winter in a small seaside dormitory town if you’re not into sailing, and too young to settle for a stroll on the pier or a bracing walk along the pebble beach?

“That teacher who was in your department plays rugby now. What was his name? Gareth spends quite a bit of time with him.”

My head aches from her talk of the past. I’ve cut my ties with Llewellyn High School, where I taught French for fifteen years and became Head of Department. “I can’t think of it at the moment.” I’ve blocked all the memories, not just the sad ones. “I expect it’ll come to me.”

She glances through the French windows at her garden where deep red and yellow roses are in bud, in bloom and overblown. She’d love me to stroll around the garden with her, but she says, “Off you go. Tenby’s a long drive. Make sure you get there before dark.” It won’t be dark for hours, but her anxiety’s a sign of how she’s aged, and my stomach clenches with pain and guilt. Surely I could relax my vigilance and spend more time with her? Gareth’s threats were angry words when he was at breaking point. If he meant me harm, he’d have tracked me down by now.

“Let’s say goodbye here.” I stop in the hall and hug Mum tight. I don’t want a long goodbye wave on the doorstep in full view of the neighbours. “I’ll see you soon.”

“Shall I give your love to Gareth when I next see him?”

“No.” I didn’t mean to snap, but the tight feeling moves from my stomach and lodges in my chest. I ease my backpack onto one shoulder. “Don’t tell him I was here. Please.”

“Okay,” she says.

At the end of her drive I turn and wave, then stride towards the main road and the pub where I parked my van. I’m still clutching the envelope she gave me with the cheque in it, and flip it over in my hands. On the back is a smudged line of text, as if the envelope had been pressed down like blotting paper on top of something she’d written underneath in fountain pen.

The letters and numbers look familiar. With a stab of shock, I realise Mum has noted down my campervan’s registration plate from the photograph. But why?

Ask Paige - Team Assistant

Ask Paige - Team Assistant

Comments

Book cover

The cover image has loaded now and I've written text for screenreaders.

The novel has just been published. Date of publication 17/3/22.

Such strong writing and…

Such strong writing and beautiful phrasing. I was on the edge of my seat with this one, part due to the pacing. Great stuff.

Thank you

In reply to Such strong writing and… by Ruth Millingto…

Thanks so much for your encouraging comments, Ruth. I'm thrilled to have made the longlist. I've started following your adventures in Colombia on Twitter - enjoying the photos and insights from off the beaten track.

Suspenseful!

From the start, we know something big is about to happen--and you follow through well. Then, the seamless flashback adds even more suspense. Well done!

Thank you

In reply to Suspenseful! by Kelly Boyer Sagert

Thanks, Kelly - that's exactly what I was aiming for so I'm delighted it worked for you.