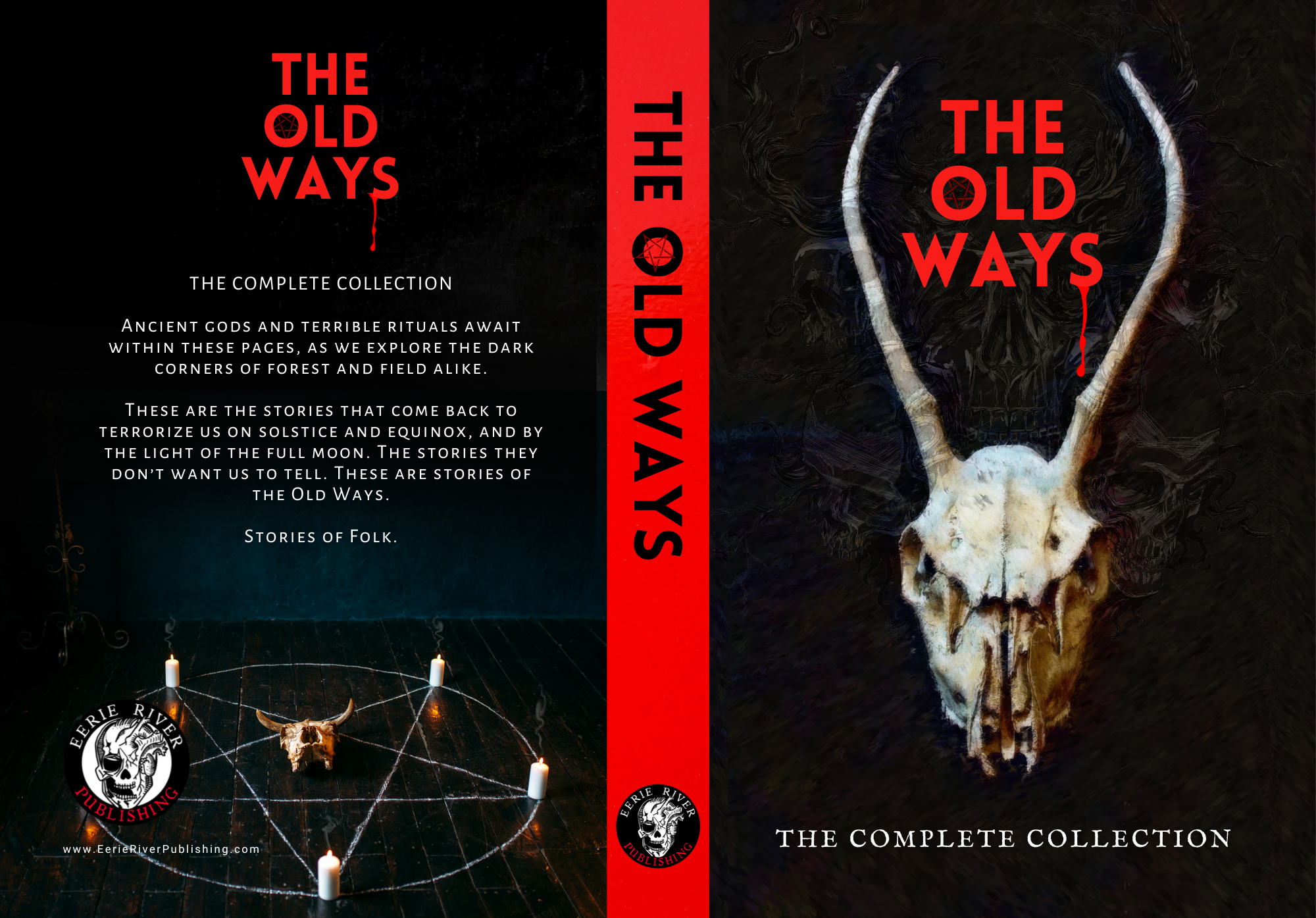

A Frolic in the Digital Wood:

The Romanticism of Folk Horror

When Romanticism swept the western world at the turn of the nineteenth century, the art filled a void, provided voices, and patched souls. Against the backdrop of an Industrial Revolution—a time when rural people were uprooted, with urban sprawls replacing green fields—Romanticism provided a reaction to what was lost. If your window gave narrow views of brick and soot, a Wordsworth poem, by contrast, treated your mind’s eye to idyllic vistas and serene lakes—a mental frolic in the face of drudgery, as it were, or a dance in the face of loss.

Romanticism is an art for times of great change.

Of course, this categorization risks the label of escapism, a term equated with intellectual insolvency. Escapism, however, isn’t always about fleeing into the imaginary countryside. Escapism also allows us to confront deeper anxieties about change. Even when escapism colludes with imagination rather than reason, it provides a window for understanding ourselves.

Folk Horror, too, is an art for times of great change.

From its emphasis on nature to the exploration of folkways, prejudices, and paganism, Folk Horror shares a great deal with Romanticism. Both movements provide the dual release of escapism and confrontation. Folk Horror, too, has blossomed against similarly trying backdrops of change.

The first Folk Horror boom began in the 1960s when the western world reeled, confronting the folly of war and the absence of civil rights. Our current Folk Horror revival occurs in a time where we battle great inequalities, while also experiencing a Digital (rather than Industrial) Revolution. In this latest uprooting, the unreal is replacing the real, and the unpalpable is supplanting the tactile. The vast internet, a digital forest, awaits us each day. This is an anemic existence for many, so the Janus-faced desire to retreat and confront is reborn, just as the desire emerged circa 1800.

Like the Romanticism of old, the art of Folk Horror can provide a voice and patch a soul, filling the void. Here moldering bones refuse to stay buried, things taken are reclaimed, tensions erupt between old and new, and rural Arcadias succumb to inspection. Through Folk Horror, we escape and confront a digital Hellscape rather than an industrial one, but the desired outcome is the same.

In The Old Ways, Holley Cornetto and S.O. Green have gathered tales that equal a frolic in this digital wood we travel, granting us escape while also delivering horrors that articulate our anxieties and confront the issues of life in the twenty-first century.

It’s a superb collection. I hope you enjoy the dance.

Coy Hall

Author of Grimoire of the Four Impostors

West Virginia, USA

January 2023

Scarecrow

By Bradley Don Richter

In San Cuervo, California, a boy is not a man until he’s smoked Scarecrow.

Every year, on Halloween night, Sam Marshall puts up the scarecrow in his fallow field. Only he doesn’t stuff it with straw.

He stuffs it with what folks in San Cuervo call Scarecrow, an herb he grows on his land and dries in his barn, an herb that smells like skunk spray.

They say it opens your eyes. Eyes you didn’t know you had.

And reveals to you the Crow.

Joe saw it once. Not the Crow—the Scarecrow growing. He knew it was a risk, but he had to see it before his eighteenth Halloween, to know if the town elders spoke true.

Joe rode his bike up to the top of Acorn Ridge, a hill overlooking Sam Marshall’s farm, on the afternoon of the Fourth of July, his eighteenth birthday. He pumped the pedals, tasting copper in the back of his throat, wishing his mom had bought him the ten-speed he’d wanted.

July’s kiln was sweltering. He peeled off his t-shirt and felt the beads of his effort evaporate in the afternoon breeze as he stared down at San Cuervo. He could see everything from up here, but Covered Bridge Park was most prominent. He watched a bunch of kids swing and slide and hide and seek. How many years until their eighteenth birthdays?

Lucky brats, Joe thought. They’ll be even luckier if they die before their eighteenth Halloween.

He grabbed his binoculars and aimed them at Old Man Marshall’s farm. He’d heard that the Scarecrow needed dappled sunlight to thrive, so he scanned Marshall’s farm until he saw a latticework structure, vined with thorny briar. He crept along the ridge, staring at the magnified circles hovering before his eyes, until he saw a lattice gate hanging open. Marshall emerged, a hoe over his right shoulder and a bag of fertilizer cradled in his left arm.

He seemed to stare right at Joe.

Joe lowered the binoculars. His heart galloped in his chest. When he found the courage to bring them back up to his eyes, Sam Marshall was gone.

He scanned until he spotted Marshall again. The old man now emerged from a shed with a watering can in one hand and a pair of garden shears in the other. Joe watched as the hunched geezer crept back into the latticework structure, leaving the gate open behind him.

Joe had never seen Marshall up close. Few had, except for some select elders, of which Marshall was the oldest. He had a crazed white beard and wore hand-sewn slacks and nothing else. Even his feet were bare, black and calloused, the toenails curled up into calcified claws. His arms were knotty with muscles from a lifetime of farming. All the spit dried up in Joe’s mouth as he took in Old Man Marshall’s most striking feature: his wholeness.

Every man over the age of eighteen in San Cuervo was…missing something.

Every man, that is, except for Sam Marshall.

Joe could only look at the old man—the whole man—for a second before turning away.

When he turned back, he saw the Scarecrow growing. There were maybe fifty plants. The stalks were about as thick as Joe’s thumb and the most vibrant green he’d ever seen. Massive, six-fingered leaves fanned out, the plant’s natural latticework. Then he saw the buds—long, tight, purple flowers with tiny yellow hairs that looked like they’d been dusted with diamonds. He’d seen a lot of flowers in his life, but he’d never seen anything as unusual as Scarecrow, nor as beautiful. The sour-sweet smell of it rode a hot summer wind up the hill, right up his nostrils.

He watched Old Man Marshall water the plants and trim the leaves for a few minutes, then he crammed the binoculars into his backpack and rode home.

Joe wasn’t sure what madness had driven him to risk catching a glimpse of the Scarecrow in bloom. He wouldn’t dare whisper a word of it to anyone.

But after he saw it, he felt calmer.

And he was a little less frightened of Halloween night.

Joe’s mother had a party for him that night. She’d done it seventeen years running, so why miss the eighteenth—and possibly the last, Joe and everyone else tried not to think as they sipped flat, chea p beer from a tepid keg. Joe’s father snuck him a red Solo cup full of it late in the evening. He chugged it, even though it tasted like lukewarm piss.

Joe didn’t give a crap about the party, the blackened hot dogs, the pity beers. He was sick of hearing his mother’s vapid friends blather on about how proud they were of Joe, as if he and the other eighteeners had done anything special aside from being born male in San Cuervo and living to see their eighteenth birthdays. And if he never had to shake another crushing hand or be pulled into the stale cologne of another man-hug from one of his father’s friends, he figured he could die happy—a thought that made him instantly unhappy.

The harsh fact was: he could die on Halloween.

He could die in seventeen weeks.

One hundred nineteen days.

Two thousand eight hundred fifty-six hours.

He’d done the math. Too many times. Burned out the batteries in his calculator.

He liked the number of minutes because it was beyond anything he could really picture. The seconds were even better. It seemed like there were so many of them.

But the seconds and the minutes were already bleeding into hours. Soon, the hemorrhaging hours would become days, weeks, months…

And that’s where it ended. That’s where it could end.

The numbers plagued him as he suffered through the lame party. The numbers, and thoughts of Mary, his new girlfriend. She told him she had a surprise waiting for him after the party, and the way she said it, he knew exactly what she meant. At least, he hoped he did.

The party ended, and his parents’ annoying friends went home. He made some small talk with his mother and father until the white wines and whiskeys they’d respectively been knocking back finally knocked them back. They passed out on the couch in front of the muted TV, playing a marathon of old war movies. How patriotic.

He slipped out of the house and met Mary at her place. Her parents were out of town. She answered the door wearing a black negligee.

“Where’s my present?” he asked.

She took his hands and placed them on her hips. “Why don’t you unwrap it?”

He did—and he took his sweet time doing it.

A little less than four months later, on the night before Halloween, Joe sat in his room talking on the phone to Mary.

More accurately, he was playing Call of Duty on Xbox. Mary was talking to him.

Screeching, really.

“Why aren’t we together tonight? Halloween is tomorrow!”

Joe grunted, distracted by the game.

“Are you even listening to me, Joseph?”

He hit pause. Sighed. “Of course I’m listening to you.”

“Good. Then maybe you’ll hear this.” But she didn’t say anything more.

A minute or two went by. Joe wasn’t sure how long. He had un-paused the game as soon as she’d started talking and had gone back into battle.

“You still there?” he asked, but he didn’t really care one way or the other.

He sensed that she wanted to talk about something serious, and there was nothing more serious than becoming a man in San Cuervo. But it was pointless to spend time thinking about it. The Crow was going to take what the Crow was going to take. If that was going to be his fate, so be it. He was better off not thinking about it.

Because thinking about it meant thinking about running.

His bag was already packed. He could take his father’s truck. Or hitchhike.

But he couldn’t run. Could he? In theory, he could. But would he?

He debated endlessly. If he left, he’d be giving up all the benefits—a plot of land, a cheap home loan, a college education, and, perhaps most important of all, a place in San Cuervo. If he left, he’d be no one, nowhere, and he’d always be looking over his shoulder for the Crow.

Joe jabbed the pause button. “Hello? You there, Mary?”

“I knew I shouldn’t have slept with you on your birthday. My sister was right.”

“Your sister’s so blonde she doesn’t even get blonde jokes.”

“That’s not funny.”

“I know. It’s a serious condition. She should really see someone.”

“Shut up, Joe. Are you coming over or not?”

“To do what?”

She scoffed. “What do you think?”

Joe knew: make babies. And there was a part of him that wanted to do just that, an aching part that said, If you die tomorrow, leave something behind. Joe ignored it. To impregnate Mary, even symbolically, would be to admit that he might die tomorrow night, and Joe wasn’t willing to do that.

And what if Mary had a son? A boy who would one day be eighteen?

“I don’t know,” he said. “I have a big day tomorrow.”

“A big day?” Her voice spiked, loud and harsh in his ear. “A big fucking day?”

“Yes. And I have a lot to think about, so if you don’t mind…”

Silence. Then she whispered, “I think I know what this is about.”

“Enlighten me.”

“You’re scared.”

“Am not.”

But he was, even though scared was too small a word to describe it.

“It’s okay if you are. Maybe I can make you feel better.”

This again. “I don’t want to give up anything. I like everything I have.”

Another long silence, punctuated by a strange clicking on the line.

“Hello?” Joe asked.

“You shouldn’t talk like that,” she said finally. “It’s blasphemy.”

“Like what? Like the Crow’s bullshit? Like he doesn’t protect us. I mean, what is he even protecting us from? And why should I have to give up something? It makes no sense.”

“You really shouldn’t talk like that. I’m going to hang up.”

“Don’t be silly,” he said. But she was already gone.

They had been raised not to question the Crow or His Harvest, not to question Old Man Marshall’s Scarecrow farm or his exclusive wholeness, to accept that every boy in San Cuervo has something to give, something the Crow needs to go on living, and that it’s not their place to question His will. The Crow protects San Cuervo and San Cuervo protects the Crow. All men are called to Give. But they’re comforted by the fact that the Crow only kills when it’s absolutely necessary, when He needs a new heart or a new liver or a new brain. And if you’re lucky enough to provide the Crow with one of these essential organs, your soul is fast-tracked to Heaven, to Joy Beyond Reckoning, Forever. And a stone is added to the Mound for you.

You may have been dismembered, but you are remembered.

The Crow has been alive a long time, longer than San Cuervo.

Back when the Mound Builders lived here, and even before. Long before.

Parts of Him failed, every year. He had to keep replacing parts to stay alive.

And if He were to die, you don’t even want to know what might happen.

But, when you’re a kid, eighteen seems like it will never come. And so you go on living, and you never question the will of the Crow, and you know that your own father went through it—he’s missing all the toes on his left foot—and you know that you will someday proudly show your own sons your own wounds, those gleaming badges that say, I did my part. I am a man.

But then eighteen comes. Then it’s real.

Then you know, on Halloween, you’ll have to sneak into Old Man Marshall’s farm with the other eighteeners, steal enough Scarecrow to roll a joint with the dried herbs, and pass it in a circle, inhaling deeply until everyone feels the effects.

How do you know when you feel the effects?

You’ll know, they say. You’ll know.

After Joe hung up the phone, he went back to Call of Duty. The pixilated unreality of the video game warfare calmed him. A night with Mary, as good as it might feel, would be too real.

He had less than twenty-four hours until the Harvest began.

Halloween came like it always did. A black cat slinking out of the darkness. All over town, chimneys blasted plumes of smoke like gigantic cigarettes into the sky where it joined the dark clouds, forming a layer of grunge that threatened to blot out the weak, pumpkin-colored autumn sun. The chill air was ripe with rotting apples. Jack-o’-lanterns stood sentry on every porch with geometric eyes and serrated grins.

Joe walked. He wasn’t sure how far, or for how long. It was morning. In five or six hours, the street would fill with ghouls and goblins and mummies and demons. Hunger gnawed at him, and he wished for a fun-sized Snickers. But he was far too old for trick-or-treating.

The streets were lined with black flags, billowing in the October wind. Many were faded from repeated use. It looked like a twisted version of Independence Day. All the townspeople Joe passed wore tiny black ribbons on their lapels in honor of the Harvest.

Joe wasn’t sure where he was going until he got there. The Memorial Mound. It was in a clearing in the woods and had been there for thousands of years. The residents of San Cuervo still added stones to it to mark the fallen. Joe stood in the dusty shade of the ancient redwoods, some of which were younger than the Mound, and tried to imagine his parents heaving a stone of remembrance onto the sacred monument after he was gone. He couldn’t picture it.

He headed home to spend some time with his mom and sister, Sally. He didn’t expect to see his father that night. Some fathers built their entire lives around being proud of their Harvest sacrifices. Others barely mentioned their eighteenth years. Joe’s father was one of the latter.

When Joe got home, he stepped into the kitchen, stared at his mother for a long time, then embraced her and cried against her chest like the child he still was.

The day faded, another rusted leaf on an autumn tree. Sally transformed into a princess. While Joe’s father was still at work, his mother took her trick-or-treating.

When they left, Sally kissed Joe on the cheek. “I’ll save my Snickers for you.”

The kid has no clue, Joe thought. No clue.

His mother pulled him into a too-tight hug. Tears filled her eyes.

“Come home, damn it,” she whispered. “You come home tonight.”

Then the princess and her chaperone queen departed.

When night had fallen, Joe contemplated running again. If he was going to do it, he had to do it now. He went upstairs and felt the weight of his suitcase in his hand, but he couldn’t find it in his heart to leave San Cuervo behind. If he could just get through this night, the rest of his life would be easy, he told himself. He took a deep breath, stuffed the suitcase back under his bed, hopped on his bike, and rode out to Old Man Marshall’s farm.

Kyle and Derek were already waiting for him there. They were the other eighteeners this year. Kyle was an acquaintance at best. Derek may as well have been an enemy. He used to bully Joe back in grade school until he discovered girls. Joe still suffered PTSD from third grade.

Their parents knew that Joe, Kyle, and Derek would all be eighteen the same year, and therefore would all face the Crow together. They arranged play dates when the boys were still in diapers. But it didn’t stick. If anything, the boys made a conscious effort not to be friends.

The truth was, Joe couldn’t see Kyle or Derek without thinking about the Crow, without thinking about that distant, then not-so-distant, now here, night when they would sacrifice pieces of themselves.

They weren’t dressed up for Halloween. They had no need for costumes this year.

“We were starting to think you weren’t gonna come,” Derek said.

Joe flipped him off. The three boys laughed nervously, partly because Joe might be losing that very finger before the night was over.

Derek pointed at the scarecrow, which was staked in the center of Sam Marshall’s field. “We gonna do this or not?”

“Who’s going first?” Kyle asked.

“You,” Derek said, and pushed him into the field. Kyle stumbled but didn’t fall.

“Hell no,” Kyle said. “I’m not going until you guys come too.”

“Fine.” Derek sighed. “Let’s go.”

He grabbed Joe by the arm and led him into the field. Joe wanted to run more than anything. And he knew the other boys did too. But none of them ran. They kept inching forward, toward their shared fate.

They finally reached the scarecrow. It stared blankly down at them.

“What now?” Kyle asked.

“We get stoned on Scarecrow,” Derek said. “I heard it’s like pot, only stronger.”

“Stronger?” Kyle asked.

“Sure. My dad said, when he did it, before the…Crow came, it was the best feeling in his life. What do you guys say we take a little for ourselves, you know, for later?”

“No,” Joe said.

He’d heard the story. It was actually a parable for the way of the Crow—take only what you need. Back in the sixties, some boys managed to smuggle a little baggie of the Scarecrow out. When their Harvest wounds had healed, they decided to smoke some of it recreationally, and the Crow came back to finish them off. He made an example of them—three boys, swinging from the Main Street stoplight in the center of town. And at their feet, the stolen Scarecrow, stomped into the asphalt.

“Fine,” Derek said. “Let’s just get this over with.”

He took a small handful of the herbs from the scarecrow’s chest and sat cross-legged in the field. Joe and Kyle sat with him, watching him grind the Scarecrow to a fine powder between his fingers, line it up on a rolling paper, lick it, then roll a perfect Scarecrow joint. He made it look easy. He’d clearly been practicing.

“Who wants the first hit?” Derek said, smiling. Was he actually enjoying this?

When Joe and Kyle said nothing, Derek shrugged, flicked a lighter, and lit the joint. The burning herb had a sour reek. A ghostly cherry hovered in front of Derek’s face. He held a deep hit in and exhaled with a coughing fit so violent tears streamed down his face.

His coughing morphed into laughter. “Smooth,” he said, and took another hit.

He passed the joint to Kyle, who inhaled deeply and coughed just as Derek had.

Then Kyle passed it to Joe. He brought it to his lips. The paper was moist with saliva. The scent was intoxicating, almost toxic. He felt lightheaded just smelling the smoke.

“What are you waiting for?” Derek asked.

Joe closed his lips around the joint and inhaled slowly. The smoke burned his throat and singed his lungs. He held it in as long as he could and then coughed up a cloud of dark mist. He immediately felt like he was going to lose consciousness. He shut his heavy eyes.

“Hey,” Derek said. “Pass that over here.”

He held out the joint. Derek snatched if from him.

Joe opened his eyes and…everything was the same. The scarecrow still leered down at him. The three boys still sat cross-legged in the field. Derek passed the joint back to Kyle.

“You guys feel anything yet?” Derek asked.

Joe couldn’t speak for the others—hell, he couldn’t even speak—but he felt it.

His entire being was a slowly opening eye.

He stood. They all did.

They surrounded the scarecrow and held hands. Derek’s hands were chubby and clammy. Kyle’s were thin and calloused. Why the hell were they holding hands? They never would have, in normal, sober life. But right now, it felt natural, almost inevitable.

They began to hum, three distinct notes, a minor chord.

The harmony rose, clashed. Overtones rang out.

Joe could see the sound, now. An orange fog, rising, darkening.

Their mouths gaped and tones poured from them like pipes on a vast organ.

The chord changed.

The scarecrow was lost in the darkness of the music they made. They could no longer see its obscure face. Soon, they surrounded nothing but the ominous sound.

And now there was a fourth note in their harmony, a complex, jangling chord.

The boys closed their eyes. They stopped singing.

One note continued ringing out, growing, pulsing.

A wavering, sour, out-of-tune note. Vomit from the belly of jazz.

Joe opened his eyes.

Standing in the center of their circle, where the scarecrow was once staked—the Crow. His massive body was covered in a cloak of black feathers like a kind of armor. The ‘feathers’ looked hard, scaly. Beneath, He was a hideous, disfigured thing, made of the rotting parts of the men of San Cuervo. All those patched-together pieces of skin, each a slightly different hue, gave His body beneath the armor the look of desert camouflage. He crouched and tucked His wings behind him. His talons scratched at the earth. He had a black beak protruding from the mask on His face, like a plague doctor in old paintings Joe had seen in History class.

The Crow stopped singing.

All was silent.

The Scarecrow joint smoldered fragrantly nearby, forgotten in the grass.

Joe saw something glinting in the Crow’s…hand? Claw? Was He a bird or a man? It was hard to tell. An old god, perhaps. A little bit of each. But He had hands. And in one of His hands, He held a hunting knife with a ten-inch blade.

He lunged for Kyle, grabbed his arm, brought the blade down swiftly, and cut off Kyle’s hand at the wrist. A jet of black blood erupted from the stump. Derek screamed. The Crow held up the severed hand in the moonlight, studied it, and stashed it away in His feathery coat. Kyle fell to the ground, howling and clutching his wrist.

Derek turned to run. He made it about ten steps before the Crow lifted off the ground, spread His enormous wings, and reached Derek in one horrifying leap. He pinned Derek down, and—using His hands that weren’t quite claws, His claws that weren’t quite hands—He popped out both of Derek’s eyeballs, admired them, and tucked them away in His plumage.

Derek remained on the ground, sobbing blood from cavernous sockets.

Joe held his ground, watching the dark shape of the Crow lurch toward him, watching the Crow’s bloody blade glisten in the pallid moonlight. He walked up to Joe, deliberately, and stood before him, looking him up and down as if deciding which piece to harvest first.

Joe closed his eyes.

He felt the blade plunge deep into his chest, splitting him open.

He felt a hand root around inside his chest cavity.

He felt his heart being ripped from his body, heard the wet snap.

His eyes opened and he watched, curiously detached, as the Crow held up his heart and examined it in the bone-colored light of the Halloween moon.

Guess I’m one of the lucky ones, Joe thought. One of the remembered ones.

He closed his eyes.

When he opened them, he’d see Heaven.

He just knew he would.

Old Man Marshall surveyed his field on the morning of November first, shaking his head.

Lots of blood, but there always was. Looked like a morning-after battlefield.

And this time, damn it, a body.

There had been three. Two of them must have made their way off the farm. But one… One would be staying to fertilize next year’s crop.

He took down the scarecrow and emptied it of its stuffing. Tonight, after San Cuervo had gone to sleep, he’d burn what was left of his crop in a bonfire. He wouldn’t dare smoke the stuff himself, and he didn’t trust having it on hand. The local boys were curious about his plants, and rightly so. He didn’t want them jumping the gun and smoking Scarecrow before their eighteenth birthdays. Didn’t want to find out what’d happen if the Crow caught wind of it.

The boy’s body left a trail of gore as Sam Marshall dragged it across the fallow field and into the latticework enclosure where he grew the Scarecrow.

Then, the old man—still whole, praise the Crow—began to dig.

Comments

CREEPY!

In a good way, but still creepy! LOL

The pacing could benefit…

The pacing could benefit from smoother transitions.