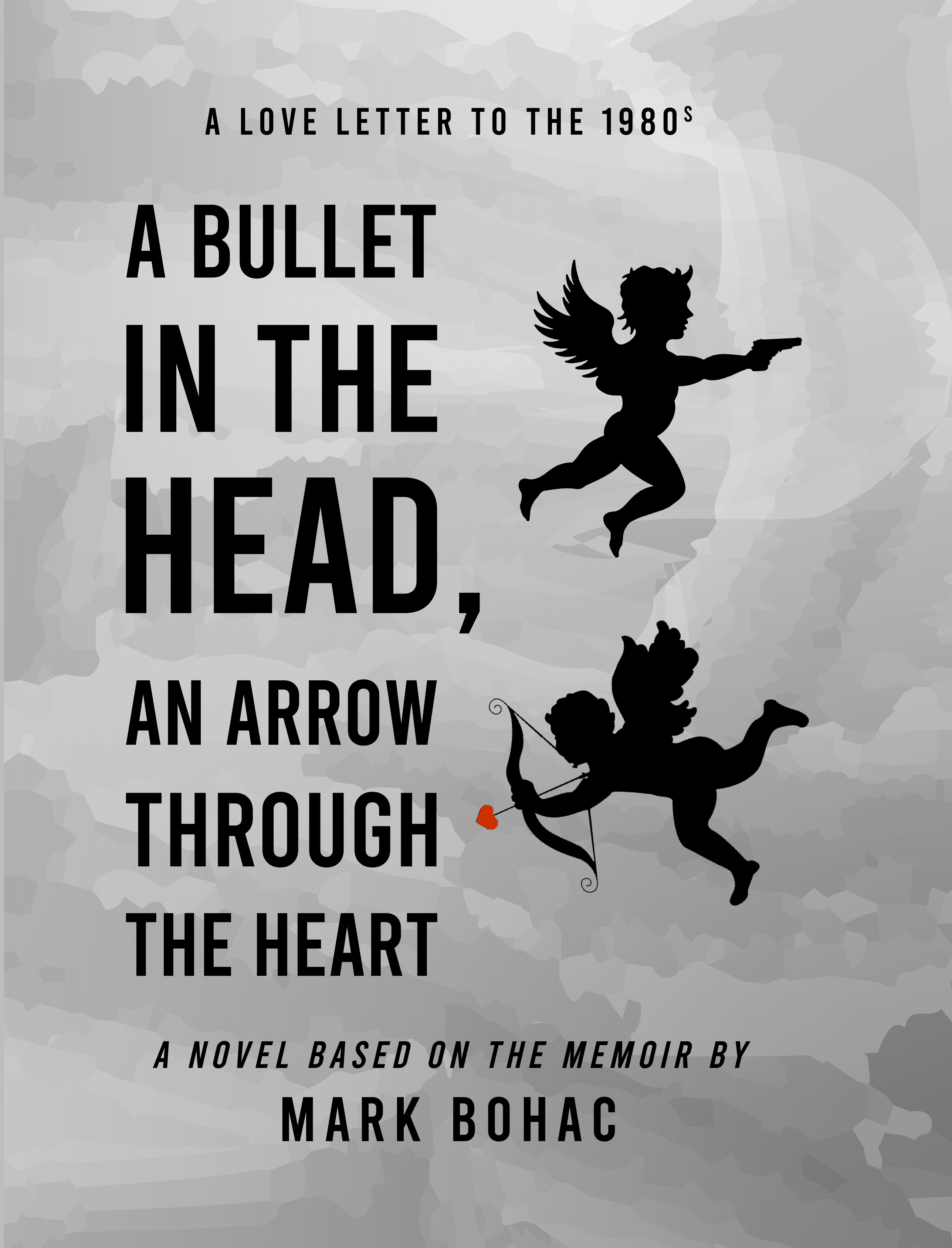

Before

Or, When I Was Twenty-Five

“I’m gonna shoot you in the head,” the man I had loved and looked up to all my life told me.

We were in the garage alone, and I was more than a bit unnerved. “Why would you do that?” I asked him.

“Because your best years are behind you,” he said.

That’s what my father told me the day I turned twenty-five.

“Your grandfather used to say that they should shoot a man when he turns twenty-five,” Dad said with a smile that was at once reminiscent but also knowing. “That’s what he told me, and that’s what I'm telling you now. It’s all downhill from here.”

I wasn’t sure why, but at that moment, Dad sounded awfully wise, like he was a seer of some sort. My grandfather would know about the best days in a life; he lived beyond twenty-five, of course.

Grandpa Bohac died at sixty-eight in 1965, so he had an opus of over forty more years on which he would draw and compare to his first twenty-five. And he apparently drew the conclusion that it was best to be shot dead at twenty-five.

I was four years old when Grandpa died. My hazy memories of him may as well have been dipped in the grayscale of all the old family photos, if not actual sepia itself. He was a real Bohemian, from the Bohemia region in what’s now the Czech Republic. You can find his name on the wall at Ellis Island.

I mostly remember my grandfather fishing up in way-north Wisconsin, on the border of the Upper Peninsula in Michigan. Every summer since well before I was born, he’d travel up to Eagle River and Lac Vieux Desert from his bungalow-style home in Chicago’s South Side in pursuit of the Great Muskellunge, or Muskie - a terrifying, needle-toothed gamefish in the pike family that could be as long as sixty inches and weigh as much as fifty pounds - or even larger if you believed the fantastical stories coming out of the North Woods. What was true was that the largest Muskie that ever came out of Vieux Desert tipped the scale at over fifty-one pounds back in 1919.

Muskies were at the top of the freshwater food chain. They’d lay in wait and ambush anything they saw fit to eat, feeding on lesser fish, frogs, ducks, and any small animals that would regret being in or around the water. They’d sometimes give chase to a sport fisherman's lure, sometimes winning the battle, sometimes ending up proudly laid-out in a refrigerated display case on the sidewalk outside the fishing tackle store in Eagle River.

Kids who lived by the oceans may have had their sharks to fear; us Midwestern kids from the Southside were afraid to be alone in the water because of muskies. At least this little kid was. A good-sized Muskie probably could’ve taken me into the depths of Lac Vieux Desert and devoured me, too, as I was but a wisp of a boy; I’d remain slight and short well into adulthood - both a blessing and a curse.

Grandpa would get his two weeks off from the Wrigley Company and spend it up there fishing. There were no other destinations, no discussions of anything to the contrary. That’s just what it was for two weeks every summer. And the rest of us followed him.

I remember him with a fishing gaff in his hands and a muskie hanging from it, or a stringer of perch and walleye that would end up dinner in our clapboard, whitewashed rental shack on Lac Vieux Desert. There was the ever-present unfiltered cigarette dangling from his lips in every photograph, too, and beer and harder stuff dotted the background. I can still see the Blatz beer cans sitting on the arms of weathered Adirondack chairs. He and his brother, my Uncle Freddie, made Keith Richards look like a sissy, like Keith was nothing but a saint smoking candy cigarettes and drinking soda pop. Grandpa and Uncle Freddie were the real thing.

It’s all there in the fading black and white photos and home movies with no sound, whose scenes are still very much alive in vivid color in my memories. I just can’t hear their voices anymore, just as there are no voices in those old, 8mm home movies.

My grandfather grew up fast and lean when he got to America, working his way to where he’d settle in the Back of the Yards neighborhood in Chicago’s Southside - home of the famous Union Stock Yards where the stench of livestock and their eventual slaughter hung in the air into the 1970s. This was the same Back of the Yards made famous by Upton Sinclair in The Jungle. It was also where Chicago’s International Amphitheatre stood until the late 1990s. We’d go to car shows and circuses and sporting events there, and the ripe smell of the livestock always let you know where you were.

Grandpa Bohac became part of a machine gun unit in the First World War. I have a photo of him and his gun battery buddies in their uniforms, and they all looked like they were already older than I’d ever become, even though they were just kids.

I remember his large hands. He came home from the war, married my grandmother, and became a stone mason who built bungalow houses on the Southside with those large hands. That promising career as a builder ended quick-like with the Depression when he lost the small house-building business he had going. Somewhere along the line, he found work at Wrigley’s, and he’d always bring home boxes of Wrigley’s Chewing Gum for us; the gum became our family go-to chewing gum brand for decades, and it was probably a contributing factor for the cavities in my molars. Even after he died, my grandmother would receive boxes of chewing gum from Wrigley’s at Christmastime. I don’t believe she received a widow’s pension, but she did get that gum every year. As a kid, I thought that was a great deal, but I’m sure it didn’t help my grandmother pay the rent.

My grandparents worked their way up the ladder a rung, maybe two, and settled off Kedzie Avenue, and we lived a block down the street from them. I remember holding Dad’s hand as we’d walk down to their house on a weekend morning, with me at a near-trot to keep up with Dad’s long gait. Funny how over fifty years goes by, and you can still recall with hi-def clarity holding your father’s hand and walking down the street to see your grandparents. So much escapes me now, but something like that is right there.

My grandfather smoked hard, and his smokes were the real deal, sans filter and packing a punch. No better way to say it than that: He smoked hard. He lived a hard life. He looked hard. He looked like Johnny Cash before Johnny Cashlooked like Johnny Cash. He looked a hundred years old at sixty. Then again, he looked like sixty at the eighteen years of age he probably was in that war photo, too.

Grandpa Bohac was retired for just a year, and he spent it going fishing and tending to his beloved roses that he grew around his house and out back by the garage in the alleyway. He wasn’t asking for much and deserved more than he was asking. He came home one day after a Sunday drive with my grandmother, sat down in his easy chair, and he was gone, just like that. He was still clutching his car keys in his large right hand.

“They should shoot a man when he turns twenty-five because his best years are behind him,” he had warned anyone who would give him an ear.

I was reminded of this particular piece of wisdom many years later when I told my father-in-law that I was closing in on my own retirement and that it couldn’t come fast enough. I’d had enough. I wanted to do my own version of fishing and gardening. I wanted to do something.

“Retire?” my father-in-law laughed as if it was the first time he’d ever heard such a curious word. “Retire!” he said again after fully comprehending the idea, this time as a recalcitrant statement of sorts. “What are you gonna do when you retire?” he roared as if it was becoming more absurd with each passing moment that he gave it thought, as if I had nothing to retire to or for, so I may just as well keep on working and then when I was even older, I’d just sit down, kick my feet up and never get out of my easy chair again.

I leaned back and boasted something like, “I’m gonna pursue my dreams! I don’t know what that looks like yet, but I think I’ll learn how to make a guitar talk and be one of those guys you see in the corner of the bar playing for tips on a Saturday night.”

“Ha!” he scoffed.

“Anyway,” I said, “I've got some dreams to chase, and pretty soon, I’ll have the time to chase them.”

“Ha!” he barked again, louder, the pain in the ass that he was. “If you haven’t caught your dreams by the time you’re thirty, my boy, you’re never gonna catch them.”

A pain in the ass is what he was.

There’s nothing quite like getting a slap-down from gruff old men who never caught their dreams. But what scared the living hell out of me was that maybe these old men were right.

Frank Sinatra sang a moody and poignant - but ultimately reaffirming - version of “It Was a Very Good Year” in 1961, the year I was born. He sang with conviction Earvin Drake’s lyrics about getting it on with the chicks up the stairs when he was twenty-one, and how good it all was. And then about getting it on with them in their chauffeured limousines when he was thirty-five and so on, until all he could do was look back at all the years where he was getting it on with chicks and deciding it was all very good.

Now, here I was, twenty-five years old and a good candidate for a shot in the head. I got it.

The song, that is. Not the shot in the head. Not quite that.

But I understood what Grandpa was saying.

Chapter 1

1983-1984

Or, Who Wants to Be A Writer?

1983. Now that was a very good year. I was going to be a writer.

I’d just graduated from the University of Dayton with a Bachelor of Arts degree in my hand and no clue in my head. My major was communications, with a heavy dose in journalism and a minor in English. I stuck around for an extra semester because of her, and I added an additional minor in psychology for what that was worth. I had somewhere around a B average. I was wholly unremarkable, and I had nothing but time in front of me. I had no choice but to be a writer because the whole college-thing was pretty much useless for anything else. I may not have known how to write, but I knew nothing else, either.

I would be a writer.

In my fiction writing class my senior year, on one of my short story assignments, my professor, a guy named James Rossi, scribbled in the margin how one passage in my story, “Perfectly expresses what you want to say,” and added “Very funny!” The rest of the story was bad, but he liked that one line, and I ran with it.

Forty years later, I don't remember much anymore about college classes and what I may have learned in them, but I remember that comment from that professor on that short story. Oh, yes, I do.

She may not have had a face that could launch a thousand ships,

I wrote in that bad short story,

but perhaps it could launch a few hundred small pleasure craft.

And it was from that line that I was sure I would launch my thousand stories.

Write, I would, too. A job at a weekly newspaper in Pickwick, a small town north of Dayton, Ohio, gave me my nascent voice. I had my own column. My editor, a roughly four-foot-tall man named Steve Timken, liked my writing and let me write whatever I wanted to write about. But I also had to do the mundane stuff like cover painfully long nighttime town council meetings and equally long and painful nighttime board of education meetings. This meant giving up a couple of nights when I would otherwise be out drinking and chasing chicks, as my friends and I were wont to do.

I had to take photos that accompanied the stories. Then I'd develop those photos on Layout Night - which resulted in still another long night every week that got in the way of drinking and chasing chicks. “The news happens at night,” my four-foot-tall editor was wont to remind me.

Steve was what they called at the time a midget. Some still do use the term, I suppose, but there are more appropriate terms now. The midget-thing novelty wore off quickly. Steve knew his craft, he was hilarious, and he helped me along. I respected the hell out of Steve. Like any other misconceptions about a guy that you come to the table with, it wore off quickly once you got to know the guy and saw what he added.

At a small weekly newspaper, photos were king. Someone puts down thirty-five cents for their local paper, they want to see photos. Not what you wrote, but what you shot.

In 1983, the Pickwick Examiner weekly newspaper existed to sell ads. People bought the paper to see photos, and in doing so, they’d see the ads. So, really, although photos were king, the king was propped up by the ads. The king had no clothes without the ads. Photos sold the papers, but the ads made the money. And ‘round and ‘round this went. This was symbiosis in action.

The only way ads were sold was if the advertiser was confident the ad would reach an audience. The ad would only be seen if the front page of the paper featured a photo of little Mary with a little American flag in one hand and a puppy in the other as she sat on a sidewalk with ice cream all over her face while watching the parade go through town on the Fourth of July. Sex sells, sure as I’m sittin’ here, but it sold nowhere near as well as the photo of little Mary and her puppy on the Fourth of July. Steve had to remind me of this law many times. If something needed to be cut on layout night because there weren’t enough column inches available, it wasn’t ads or photos. We’d write simply to add more pages to that week’s edition, and more pages meant more space for ads and photos, and our writing served to fill in the space around both.

I wanted to write, but the only way I could write was to include photos. If I wanted somebody to read my story about a busted water main on Elm Street, then I’d better have a photo of the busted water main on the page with it. Better still, if the busted water main could show a dozen little kids dancing around the geyser spewing a fountain thirty feet in the air or a car submerged in the sinkhole that formed around the main as water sprayed all over the place, the story was certain to be read.

Let’s say there was a relatively important story about how to file for a certain property evaluation exemption that could enable some homeowners to pay less property tax. Or maybe, at the school board meeting, there was a discussion about the need for a new roof and HVAC system at the high school, which would result in a new bond proposal that could raiseproperty taxes. Or maybe there was a very well-written, heartfelt, funny, coming-of-age column by the new staff writer. If those stories didn’t include photos like little Mary and her puppy at the parade, nobody ever read them. Only the weirdos who wrote letters to the editor read the stories without photos. Nobody ran out and bought ten copies of the paper to hand out to their friends about some coming-of-age column story - and with no photo to boot! But you could bet the house they’d lay down good money to buy twenty copies of little Mary and her puppy at that parade. And they’d see those ads, too.

So I had to shoot and develop photos, and my Canon AE-1 and I became a nice pairing. I also had to deliver the papers to stores and newspaper vending machines, then collect the money from those machines later in the week. Sometimes I even had to deliver papers to homes when the regular delivery driver was unavailable. On a small, weekly newspaper in Ohio in 1983, writing was just a side hustle. Editor Steve had to remind me of this law quite often, as well.

But I'd do my own writing on the side. Sometimes. But in 1983, what I mostly did was Carmen.

Carmen was the girl with the face that could launch a few hundred small pleasure craft. When wires cross and crackle, all else goes abandoned in the dark. Her eyes arced cool blue and hot silver sparks like the lit fuse on a firecracker. Her smile hinted at a sexual power of which even she had no knowledge. Not yet, anyway. It was about to be discovered, and I was there for the Eureka! moment.

I was a senior at the University of Dayton, she was an incoming freshman, and we became We. I first saw her on campus late in 1982, but I met her in the spring of 1983 in Timothy’s, a worn and tired bar at UD that smelled equal parts piss, beer, and smoke - and that was after it was cleaned-up at night. It was just a couple of months prior to my graduation.

“I’m Carmen,” she more yelled than spoke in the crowded, sweaty-hot, way-too-loud, cloud-filled bar. And then she reached out and wiped the sweat off my brow with a bar napkin like a latter-day Saint Veronica.

"Like Carmen from the opera? Is that who you're named after?" I said reflexively, realizing I sounded either purely stupid or possibly intelligent. Fortunately, she knew what I was referencing, and things seemed to be okay. "Things didn't end well for that Carmen or her boyfriends," I said with a laugh.

She smiled and laughed along with me. “I’m not really all that familiar with that opera,” she admitted, drawing nearer to me as she spoke; I was glad, now, that it was so loud in the bar.

“You will be soon,” I said, pulling back to look into her eyes.

“I will?”

“Yeah, when I take you to it one day.”

I made all the usual inquiries and began my pursuit of my own Carmen. By March of 1983, we were together. And the riches were laid at my feet. The rest of 1983 disappeared into discovering Carmen. Time defied all laws that year, either coming to a halt in the vacuum out in the universe or slipping past like a light year; I couldn't tell, and I didn’t care. There was us, and then there was the rest of the world going on around us.

The Cubs were on the verge of winning the 1984 NLCS against the Padres the next summer when I was visiting Carmen at her parents’ home in little Alma, down in the southeastern corner of Ohio, where life slowed. This would normally be cause for much celebration on my part as the Cubs hadn’t been in the playoffs in nearly forty years, but I wasn’t thinking baseball. The Cubs would go on to lose that series in dramatic fashion, but I didn't give it much thought as we laid on a blanket spread onto tall summer grass that swayed in the middle of a field in some state park whose name is now lost to the fog. It was there, on an endless summer day, when time simply didn’t apply, where it seemed most physics of any kind didn’t apply. It was all just there, whispering in the grass.

Long walks holding hands, taking rides at night to go park somewhere in the woods and make out, listening to McGuffey Lane play country rock at a festival, going to the American Legion Steak Fry on a Friday night under a summer sky filled with stars that I never noticed before, stars that now kept time for us. One night, we walked into the Alma Cemetery, and we sat atop a mausoleum of some interred family named Dann, and we drank warm beer while watching the Big Dipper up in the sky. She whispered to me, “If you love me, don’t ever stop trying to prove it.”

There was nothing else, and it was everything there ever was, everything that there could be. Who needed physics? Who needed anything more? And who needed to make money?

Not me, as it turned out.

Sure, I was working at the Examiner. I was writing, sort of. And I was so poor it was legendary. I was making $11,000 annually. Granted, that’s a 1984 salary, which translates to a nowadays salary of… still poverty-level money.

And it’s here when you reach the crossroads of Chasing A Dream Avenue and Selling Out Boulevard. I had everything, but I had nothing, too. I wanted it all.

The thing is, you don’t always see Selling Out coming. Sometimes that road isn’t clearly marked.

Which way was I going? I had about as much an idea on that as any twenty-two-year-old with a communications degree could have.

______________________________________________

We moved to Centerville, Ohio, in 1972, when Dad was transferred out to Dayton from Chicago to manage a manufacturing plant for the Continental Can Company. As an eleven-year-old, it didn’t get more traumatic than that. I was lost.

Big Dan was my earliest childhood friend in Centerville. We bonded over our combined failure to ever make the high school varsity soccer team, over bloody backyard football games that would always start out as touch games but ended up in tackle, over summer days spent at the Black Oak Swim Club, where we ogled the unattainable Bannon Twins and Lynn Heffernan during their swim team practices, and over winter nights when we’d hide behind a clump of trees on a hill at the intersection of Bigger Road and Black Oak Drive where we’d rain down snowballs on passing vehicles, sometimes finding ourselves on the run and perilously close to being caught and beaten.

And then there was the art. From early on, Big Dan and I shared a love of music and books and film. We’d hang out at the local record store, Dingleberry’s, like all the rest of the losers who couldn’t get and didn’t know how to get chicks. Dayton was famous for the Wright Brothers; for me, what made Dayton famous was Dingleberry’s.

Dingleberry’s was, looking back now, the hands-down greatest record store anywhere on earth, and it was right there for us in Centerville, Ohio. To us, at first, it seemed like an oddity, like a Spencer’s Gifts for potheads and music lovers in tandem. It was a warm, welcoming bosom for dopers that, oh-by-the-way, sold records, too. It was little more than a dark, wide hallway with jewelry cases filled with pipes and rolling papers, bongs and hookahs, and a vast assortment of roach clips. I never heard the word paraphernalia before I walked into Dingleberry’s. It sounded exotic.

A diverse range of albums were stacked in boxes and stood-up in crates, with artists and music that you just didn’t see in the department stores. There was reggae and jazz and bootlegs galore. Music and counterculture magazines and offbeat books could be found there. Of the bumper stickers and posters and scattered t-shirts on the walls, the most recognizable names to us were Grateful Dead and Cream and Todd Rundgren; beyond that, the names were, to me, obscure or local.

The place was beyond hip and edgy, but Big Dan and I didn’t really know that; we went there for the records. Why we never really took up smokin’ dope is one of those things you can never put a finger on. It reminded me of how my Dad told me his mess kit during the Big War always came with a side ration of a pack of smokes - yet a cigarette never touched his lips in his life. That small decision probably gave him forty extra years of life. Just by accident.

The store expanded from its walk-in closet to a full-blown recordpalooza place in the late 70s when it took over the attached massive warehouse space behind its walls. It had a stage and a movie screen, and it showed these weird and wonderful music videos on weekends - a first anywhere. Let me say it again: anywhere. It was a great, progressive idea that would soon be introduced to the world via something called MTV. The store was a big promoter of the local music scene, too, and big-name musicians visited the store when they came through Dayton - names like Michael Jackson, Todd Rundgren, Charlie Daniels, and more.

Dingleberry’s had a jingle set to the music of the main theme of Oklahoma! which was pretty cool, we thought. It was sung by the Dinglebears.

Dingleberry’s (whip crack)!

Where the merry record shoppers roam

Where the folks go ape

At their jewelry, tapes, records, and pot holders for the home!

Heavy is the head that wears the crown, though. When it closed in the early Aughts, a simple sign repurposing and paraphrasing a George Harrison title hung in its window:

All good things must pass

Anyway, Big Dan and I came to at least learn about chicks through music and books and films. And a by-product of all that artsy stuff between us became our inside language, and it manifested itself in wry, dry humor that only we got.

We called him Big Dan because he was the tallest among us at roughly six feet, give or take. Big Dan was also the artist among us, the scholarly one, and this said something about the rest of us, but it also didn’t, as the rest of us were not exceptional philosophers or poets or thinkers.

Big Dan dreamed of better things and therefore had a sensitive nature. At the same time, he possessed an at-times unharnessed physicality that would serve as our best line of defense in a dire situation. He was Irish, after all, and once you’d get his ire up, he was someone you’d rather avoid lest you get caught up in a tangle of haphazardly flung elbows and knees, or he’d tree you.

Well into his twenties, Big Dan was always treeing Shark. Shark would get under Big Dan’s skin, and next thing you knew, he’d be chasing Shark off balconies, had him running through yards, and got him climbing up trees to escape. Dan wouldn’t climb trees, so Shark was always safe up in the canopy. After a while, with all this experience getting treed, I would’ve put Shark right up there with a Rhesus monkey in tree-climbing speed and agility; he became a natural.

I’ve got scars on two fingers of my right hand that I sliced open on a cement trash can that I desperately grabbed at as a sudden-stop brake to evade Big Dan as he chased me down a street, and I've got a scar on my left thigh that I had to have stitched up when he threw me into the corner of a nightstand in a Michigan motel room. Some friends leave an impression on you, others leave permanent physical scars.

Fancying himself the artiste, Big Dan wanted to write, as I did, or act or photograph or otherwise create. But for the time being, he was doing telemarketing. He looked the part of the artiste, too, like a beefier Jeff Goldblum. He’d rub his chin as he considered things, and he’d use his hands and point his finger to emphasize the points he was making. When he wasn’t doing something stupid with us, he seemed to embody the aura of a sixty-year-old sage. He enjoyed cigars and Scotch, classical music, reading Tolstoy and the rest of the Classics, and he had a subscription to The New Yorkermagazine, which Shark and I found odd, but I got him. He was our Big Dan.

Big Dan would always be up for a dare, too. Nudity? Not a problem for Big Dan. Going up to any chick anywhere and saying something we dared him not to say? Also not a problem. Giving a rat’s ass about what anyone thought of him? Never an issue.

We went through our obligatory beer bong phase in the summer of 1984, where we kept records of who drank the most beer the fastest. We kept a record of the standings on a large poster board in the apartment shared by Shark, Johnny V, and Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy. There was no artwork or anything else on the walls, of course, but there was this large posterboard of hastily scribbled beer bong results and standings slapped up on the living room wall, ever so slightly atilt.

Big Dan eyed the standings one summer day and announced it was time he put to rest the question of who could drink the most beer the fastest.

We prepped the beer bong. It was basically a two-inch diameter, clear, flex hose attached to a large funnel. The funnel was held high above the drinker’s head, and a beer was poured into it, and the liquid furiously shot down the hose tunnel into the waiting mouth that was wrapped around it, hitting the lips with such force that the drinker had little choice but to open up and take it straight in. A respectable chugging time for a can of beer was about five seconds, maybe a little less. Sometimes you’d push it to two beers or three beers at a time, and a good time was maybe fifteen seconds for that.

Big Dan signaled he was ready, and a steady stream of beer began flowing into the hose. One beer, two beers, a third beer… and three more beers followed after that to much ado and shouted encouragement in the apartment from the lucky half-dozen witnesses present. Big Dan downed an unthinkable six-pack of beer in nine-point-one seconds! Let that soak in. That’s about one and a half seconds per beer times six.

Doubled over, unable to stand straight up, probably due to confused and contorted organs under sudden assault, Big Dan swung his arms wildly, motioning for us to get out of the way. “Clear out!” he managed to mumble, almost unintelligibly, like a possessed Linda Blair in The Exorcist as he stumbled hell-bent for the kitchen, knocking chairs and people out of his way, reaching the sink where he opened wide to allow a hellish pillar of vomit the color of old sunflowers to project into the sink and pretty much all around the countertop and backsplash in a spectacular shower.

It was 1984, the Summer Olympics were in Los Angeles, and many records would be established to much fanfare. I can’t recall a single thing about those Olympics now. Big Dan’s record, though, would stand into perpetuity.

That was something.

______________________________________________

“How’s the writing coming?” Big Dan asked me as we watched a freight train rumble slowly past us on an elevated train track platform in the dark after a night of drinking in the Oregon District bars in downtown Dayton later that summer.

I nodded and considered his question for a moment. “I think you gotta suffer to write, so I think I need to do me some suffering.”

“That’s the biggest bunch of bullshit I ever heard, Bo,” Big Dan said after deciding my response was unsatisfactory. “Watch this!” he yelled, springing up and flinging his half-filled can of beer at a passing box car.

Who needed to write? I thought. I sure as hell ain’t suffering, so how could I write?

I grew up in a world I thought to be much like Leave It to Beaver. That’s what I thought, at least. My folks weren’t poor, but they didn’t have money. Thing is, I never knew that. I never felt that. I pretty much had whatever I wanted as a kid, or so it seemed to me. I was a happy kid.

We lived in a few houses during my early childhood, but my memories are mostly of a happy, lower-middle class, mostly Polish-Slavic neighborhood on 82nd Street off Pulaski Road, close to Midway Airport, which was in decline and would be mostly abandoned by 1973 before beginning its renaissance. My older brothers would crawl through breaks in the fencing to ride their bikes on the silent runways dotted with robust weeds taller than me pushing through the cracks on the tarmac scorched by the summer sun. Then they’d drag me along with them to the hobby shop on Pulaski, where we raced slot cars on the elaborate layout that took up half the floor.

The neighbors on our street all got together and had block parties in the summers. A mishmash of cops and firefighters and plumbers and roofers and the occasional office guy like Dad would haul picnic tables and ice boxes and charcoal grills into the barricaded street, and the women like my Mom would prepare a blue-collar feast of burgers and kielbasa, corn cobs and cold Campbell’s beans, and potato salad and chips and it was on.

I did not suffer.

Years later, my oldest brother, Jim, told me at Dad’s wake that what I saw as Leave It to Beaver was more akin to The Island of Dr. Moreau. There was an awful lot of alcoholism in the ol’ ‘hood and wife-beating and absentee fathers and such. It was the stuff that happened when your dreams didn’t quite pan out, and you ended up in a place that was more of a beaten-down, just this-side-of-the-wrong-side-of-the-tracks neighborhood than what my six-year-old memory told me at the time.

“You thought we lived Leave It to Beaver,” Brother Jim told me. “Fact is, we were not the norm in that neighborhood. We were the exception.”

I would have preferred not to have learned this truth from my brother. I was fine with thinking I grew up like the Beaver. Sadly, getting a glimpse at what was really going on behind the curtain was the sort of thing that would happen a lot as you grew up. But I did not suffer.

My parents lived for their three sons. They strived their whole lives to push us forward. I didn’t learn until years after the fact that Dad - who had retired after nearly forty years working quality control at Continental Can Company - had to go back to work at the Defense Electronic Supply Corporation in Dayton for a few extra years in order to pay for my college tuition. I never gave thought to how my tuition was being paid. And, again, I would have preferred not to have learned this because now I feel guilty as hell. Being a good little Catholic, and even an altar boy, I was good at feeling guilty.

And in 1983 and 1984, well, I never suffered then, either. I was in love. The writing - at least the real writing - could wait. I had time ahead of me. I had all kinds of time ahead. And I had Carmen.

It was just too bad that 1985 had to come along.

Comments

There's a lot of telling…

There's a lot of telling going on but fortunately none of it feels too expositional. However, there are opportunities to relieve the reliance on prose by adding snippets of well-placed dialogue.

Thanks, Stewart! I…

In reply to There's a lot of telling… by Stewart Carry

Thanks, Stewart! I appreciate what you’re saying. See my comments below to Jennifer. I agree that there are likely some places where I could add bits of dialogue in these opening pages that would enhance/improve. Whereas these opening pages are heavy in “tell,” the rest of the novel is pretty much all dialogue. But I do see your point! Thanks for the suggestion!

Thanks, Stewart! I…

In reply to There's a lot of telling… by Stewart Carry

Thanks, Stewart! I appreciate what you’re saying. See my comments below to Jennifer. I agree that there are likely some places where I could add bits of dialogue in these opening pages that would enhance/improve. Whereas these opening pages are heavy in “tell,” the rest of the novel is pretty much all dialogue. But I do see your point! Thanks for the suggestion!

I agree that there are good…

I agree that there are good places you could add dialogue to show, not tell. But overall, it's a good start.

Thanks for the feedback,…

In reply to I agree that there are good… by Jennifer Rarden

Thanks for the feedback, Jennifer! I wish you could have access to more than the first ten pages! The bulk of the rest of the book is pure dialogue! These first few pages simply lay the groundwork for the story.