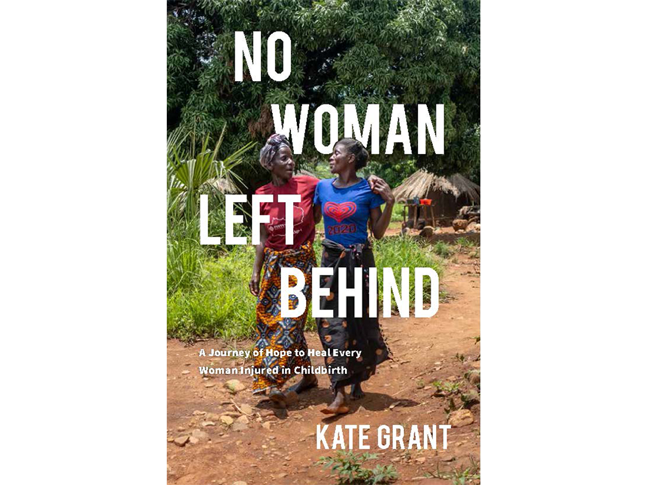

No Woman Left Behind

Prologue

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, August 1994

Put your ear down close to your soul and listen hard.

—Anne Sexton

An ancient cab, the color of moss, speckled with rust, hugged the curb outside my hotel. I got in and asked the driver if he could take me to the Fistula Hospital. We made our way onto the road, nestled behind a bus that belched gray clouds of diesel smoke into the crisp morning air. Out the window I could see a snaky train of haggard women, skinny men with a few missing limbs, and bony kids on foot. Ethiopia had recently emerged from decades of a communist dictatorship and endured a famine of biblical proportions; think rock stars singing “We are the World.” The human toll of that brutal history was trudging by us.

A few days earlier at Dulles Airport, a silver-haired stranger had asked me with a smirk “Are you a mercenary, a missionary, or a misfit?” when I’d told him I was headed to Africa. The answer should have been easy. I’d spent my twenties largely unburdened by introspection, enjoying the spoils of my Madison Avenue career. In search of a more meaningful path, I’d landed in Washington, DC, working on Capitol Hill. I liked to think of myself as a pragmatic idealist out to save the world. But maybe I was kidding myself. Maybe I was just a misfit trying to escape the rat race.

I was in Ethiopia as part of a “Co Del”—short for Congressional Delegation—and the embassy suggested that I visit the hospital. “It’s for women, you’ll find it interesting,” was all I’d been told. I mulled over the word fistula. It meant nothing to me. I had a vague memory that Italy occupied Ethiopia in the 1930s. Was fistula a proper name, and the hospital was named for a “Mario Fistula” or some other long- dead Italian who may have endowed the place?

Then, the car darted off the main road, making a hard right turn. We drove past a small green sign with white lettering that said “Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital” in English and Amharic and a wall topped with broken glass stuck in cement. A large open metal gate led into a courtyard.

As I got out of the cab, the lush green lawn and purple bougainvillea surrounding the hospital surprised me. Large trees shaded the two- story, white-washed, tin-roofed building from the morning sun. The chaotic noise of horns and car engines on the main road was gone. The only sound was the soft murmur of conversations that emanated from women in ragged clothes sitting on benches in front of the building.

I opened the front door and stepped into the cavernous entrance. The unmistakable smell of disinfectant was a sharp contrast to the strong smell of urine I noticed while walking by the women who occupied the benches outside. The ward looked like something out of a history book from the days of Florence Nightingale, with row after row of beds.

An older white woman wearing a doctor’s coat and practical flats walked toward me. She smiled and said, “Hello, I’m Catherine Hamlin. It’s lovely to have you visit us.”

Her sparkling blue eyes and Australian accent put me at ease. She was slender and towered over me and everyone else. As she escorted me to a few plastic chairs off to the side of the ward, she asked about my trip and then offered me tea.

Before I could expose my complete ignorance about fistula, Dr. Hamlin explained what it was. “Dear, a fistula is a hole between an internal organ and the outside world that shouldn’t exist.” She paused,

then continued. “And in the case of all the women here, the cause is unrelieved obstructed labor. The hole is between the bladder, vagina, and sometimes the rectum, leaving a woman incontinent. Surgery is their only hope.” Ok. Got it. The smells both inside and outside now made sense.

We were soon joined by an Ethiopian woman that Dr. Hamlin introduced as Mamitu Gashe, who she explained was a former fistula patient who now helped with fistula surgery. Mamitu was short in stature but had a giant smile and big expressive eyes. She gently shook my hand.

I asked Dr. Hamlin how she had ended up in Ethiopia. She explained, “I came here in 1959 with my husband, Reg. He, too, was a doctor, and we thought we’d stay a few years.” She laughed then added, “Things worked out differently than we’d planned. We continued to meet patients with fistula. They had often been turned away by other hospitals because of their odor and the stigma from their incontinence. We felt we needed to do something for them.”

That something was the hospital we were sitting in. She said it had opened in 1974 and was the only hospital in the world dedicated to treating women with obstetric fistula. She added, “In places like the US and Australia, most babies are born in a hospital and obstructed births are treated with a C-section. This means where you live, fistula is almost unheard of.”

She then suggested that we take a tour of the floor and meet one of the patients. When we got closer to the bed, I smiled at the young woman. Her expression was blank, and I figured she had reason to be wary of me. She was striking, with high cheekbones, large brown eyes, and skin the color of coffee with cream.

“This is Hanna,” Dr. Hamlin said. “Mamitu, can you ask Hanna to tell us what happened to her?”

Mamitu turned to Hanna and asked her a question in Amharic. I waited for the translation, which took a while because Hanna had a lot to say. “She married a young man from her village when she was seventeen and soon become pregnant, but after five days of labor at

home, she delivered a stillborn baby boy. She awoke to find herself in a urine-soaked bed. She hoped it would go away, so she stayed in bed as much as she could. But it wouldn’t stop. Her husband hated her smell and built a separate small hut for her to live in. It was so lonely. That was about five years ago. But when her mother heard there was a hospital in Addis to help her, she sold a goat to pay for the bus fare. It took several different buses to finally reach Addis.”

Mamitu then asked Hanna another question, and a smile radi- ated across her face. While I didn’t understand Amharic, it was clear something good had finally happened to Hanna. Mamitu explained, “She said arriving at the hospital and seeing other women with her problem made her feel less alone and less sad.”

Dr. Hamlin added, “We were able to close her fistula yesterday. It was an easy operation, and she should be able to go home in two weeks once she’s healed.”

I shook Hanna’s hand and squeaked out the only word I knew in Amharic, “Ameseginalehu,”—it means thank you.

Dr. Hamlin and Mamitu took me around the rest of the hospital. Like Hanna, most of the patients seemed quite young. She was only seventeen when she developed a fistula. What was I worried about at her age? My lack of a prom date? The growing realization that I’d never be pretty like my sister, as smart as my dad, or as charming as my mom? I definitely wasn’t mourning a stillborn child, facing rejection by my husband, or struggling to find treatment for holes in my vagina and bladder.

As we walked back toward our seats, Dr. Hamlin said with a tender tone, “They come to us often malnourished and usually clini- cally depressed.” She stopped and turned to me, looking into my eyes, “There are so very many of them. They will break your heart.” The compassion in her voice and the intensity of her gaze was riveting. I could feel her love for her patients in the tenderness of her words. I gazed at the vast ward of patients that were going to get a new shot at life because of this humble giant. A lump rose in my throat and my eyes started welling up.

But then, Dr. Hamlin’s black dog began nipping at my heels trying to play. It made me laugh and the threat of tears vanished. After a few more minutes, it was time for me to go. Dr. Hamlin had a hospital to run. As we walked toward the door, she joked that she was a “professional beggar” with her constant need to raise funds to keep the place going.

“It must be a challenge,” I said, thinking that was obvious.

I knew I’d just met a few people I’d never forget: Dr. Hamlin, Mamitu, and Hanna. I wished I had money to write a big check to help keep the place running. But, at that point, what I had was residual debt from grad school and a ten-year-old Honda that badly needed new tires.

Within a few weeks, I was in Cairo for a once-in-a-decade Inter- national Conference on Population and Development, the ICPD, along with thousands of delegates from the 179 members states of the United Nations. The conference produced a 104-page Programme of Action. Years in the making, it was essentially the world’s blueprint for addressing poverty, covering critical problems like accessibility of contraception, education, and safe drinking water. But absent from that ambitious, detailed document was the word “fistula.” In 1994, the world did not acknowledge the plight of a million women like Hanna, let alone have a plan to help them.

........

The day a woman gives birth is the day she is most likely to die or be grievously injured. The biggest difference in health outcomes between rich and poor in our world is in the odds of death due to pregnancy or childbirth. As Justin Trudeau proclaimed, “poverty is sexist.” For a woman in sub-Saharan Africa that lifetime risk is 1 in 41. For an American woman it is 1 in 2,700; for a woman in the EU, it is 1 in 11,500. For every woman who dies, an estimated twenty are injured, some seriously. We tell ourselves that all lives have equal value, but this data reveals a very different story.

The late Egyptian public health leader Professor Mahmoud Fathalla said it powerfully: “Women are not dying because of diseases we cannot treat. They are dying because societies have yet to decide their lives are worth saving.” That negligence also causes disabling injuries, like fistula. The most immediate victims of the losses of life and health are women. But the ripple effects stretch far and wide: to children deprived of mothers; families missing wives, sisters, and daughters; communities and nations cheated out of the contributions of multitudes of women. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Fistula Foundation was founded in 2000 to help support Dr. Hamlin’s work in Ethiopia, powered by volunteers for the first few years. Since then, we’ve expanded to fight fistula globally. Caring people in more than seventy countries have contributed $150 million and counting to support dedicated surgeons in countries across sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. These valiant doctors have enabled more than one-hundred-thousand courageous women like Hanna to get their lives back. Our small but mighty largely female team now support more surgeries for women with childbirth injuries than the United Nations or USAID, the US Government’s foreign aid program.

This book is the unlikely tale of how we got here. Part of that story is mine about finding the path that brought me to the Foundation. I’ve run into dead ends that I thought were through streets, fallen flat on my face, confronted obstacles I created and shortcomings I tried to deny. But my work has given me rewards that money can’t buy and taken my heart to places my younger self didn’t know were possible. That’s in large part because of the people I’ve been so fortunate to meet and learn from along the way.

I have had the great privilege of partnering with extraordinary men and women on the frontlines of healthcare in Africa and Asia. They’ve built hospitals, braved murderous violence and oppressive forces of patriarchy, and provided women with a new shot at a healthy life. They’ve shown me the saving grace of gratitude and the matchless joy of working with others to accomplish goals bigger than ourselves.

I’ve been inspired by courageous patients who face a formidable injury that too often relegates women to lives as outcasts. I’ve met deeply empathetic people who step up to help women they likely will never meet receive life transforming surgery. I wanted to try to share their stories and mine with you.

Comments

Excellent. Telling it like…

Excellent. Telling it like it really is without any window-dressing. Perhaps if this were to be made compulsory reading for western politicians, something really practical could be done to alleviate this disturbing problem. Apart from pop stars of course!

Emotionally powerful and…

Emotionally powerful and informative. Excellent narrative voice and pacing.

Excellent way of…

Excellent way of storytelling, keeping me captivated.

Beautifully written,…

Beautifully written, powerful descriptions and backstory slotted in very well. I have had the privilege of visiting Ethiopia and could easily visualise. Congratulations for writing this piece.

A blend of cultures!

I enjoyed reading this and the pacing moves as grippingly as the settings of the story. I'd like to see the rest of the story and how the conflicts are resolved.

So powerful.

This is so powerful and well written. Some of the statistics you bring in are horrifying. This shouldn’t be where we’re at in today’s world. Well done for drawing attention to this issue in such a compelling way. I will definitely be reading more of this story.

A stark viewpoint

A stark viewpoint into the reality of childbirth and its effects on the body. Great descriptions, powerful writing, great pacing.

Tremendously powerful

This is tremendously powerful and expertly crafted. The statistics woven throughout are genuinely shocking—it's appalling that such issues persist in our modern world. The writing is beautiful, with evocative descriptions and backstory seamlessly integrated. Having visited Ethiopia myself, the scenes came vividly to life. Well done for highlighting this important subject so compellingly—I'm keen to read more.

compelling

This compelling memoir opening effectively interweaves personal journey with powerful advocacy for maternal health, anchored by the visceral 1994 Ethiopia hospital visit that introduces readers to obstetric fistula through vivid sensory details and heartbreaking patient stories. The writing is clear and accessible with strong emotional beats, though occasionally it leans toward earnest idealism that borders on self-congratulatory, and the "mercenary, missionary, or misfit" framing device feels somewhat forced.