They are places of privilege.

They rarely include black students. In the 60s, they almost never did.

The Paradox and the Sphinx

There are private schools all across the country, places with better resources, better teachers, better budgets. By definition, these schools are not for the public. They are private. They are exclusive. They are for those who can afford better. Rarely does that include black students. In the 1960’s, it almost never did.

And then there are the ultra-elite private schools, the super schools; places where the resources, the curriculum and the tuition are comparable to the best liberal arts colleges. These are schools that taught computer programming to high school students using the same state of the art machines that NASA used, and offered classes in Russian taught by a Russian countess. These are schools that served London Broil in the cafeteria, along with eclairs that rivaled the French patisserie around the corner. These are schools where lineage is a factor in the admission process. These are not schools for those who can afford better, they are schools for those who can afford only the very best.

These are places of privilege.

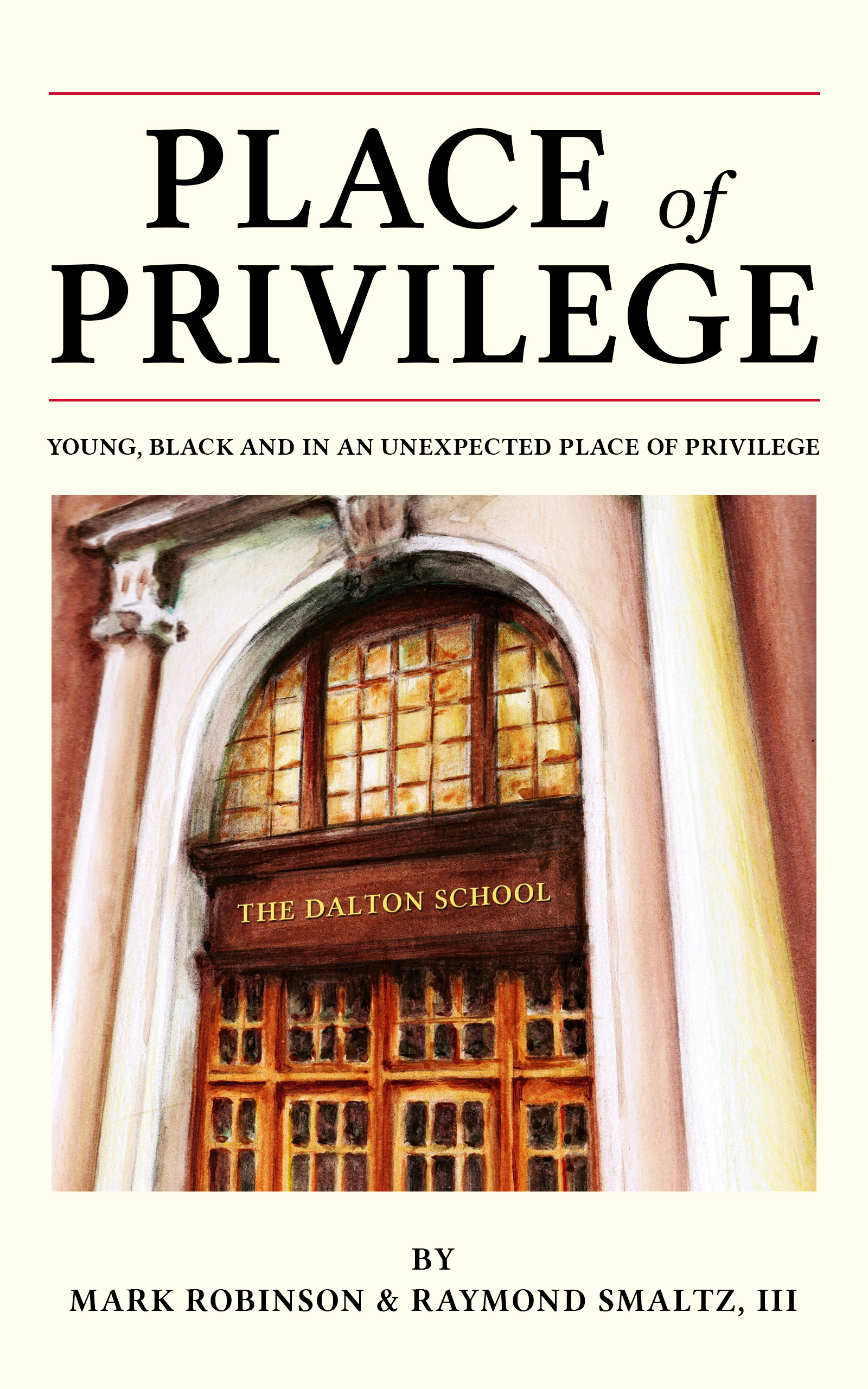

Think that’s an exaggeration? Let’s put that in terms of simple dollars and cents. In New York, the average tuition (2018/2019) for a year of private high school is $24,011. That’s $2,000 per month. And that is an average that includes many subsidized parochial schools. New York’s ultra-elite private schools are in a different league entirely. At New York’s top 100 private schools, tuition begins at $50,000 and continues to climb like a Saturn rocket. The Dalton School, our alma mater, boasts one of the lowest tuition rates in its peer group, with $51,350. One year of tuition at THINK Global, a progressive “alternative” school on the Upper West Side of Manhattan costs $85,500. What if you have more than one child?

What kind of income do you need in order to climb this walled garden?

Sure, most of these schools offer financial aid and scholarships for students who cannot afford the prohibitively high tuition. But unlike colleges and universities that also have huge endowments, the admission process at these private schools is not “need-blind.” That means that the applicant’s need for financial assistance becomes a significant factor in the school’s decision whether to admit. It means that financial disadvantage becomes admission disadvantage. Unless the school is trying to fulfill a diversity objective, this means that minority students with excellent grades and test scores are not competing equally with their affluent white counterparts.

What happens then is that the school’s own diversity objectives become a Catch-22. Minority students are admitted, but then automatically assumed to be less worthy of a place at the table, because “diversity consideration” was given. So is it worse to be stigmatized by your teachers and fellow students, or to be excluded altogether? You might insist that there has to be a third option. Most of the time there is not.

Furthermore, when they are the beneficiaries of financial aid or scholarships, students and their parents relinquish a degree of agency in their relationship with the school. The school knows that you did not pay “full sticker price.” The school knows that you are the recipient of their generosity. That takes a lot of the punch out of your role as the “customer” and the school knows it. They want you to know it too. You can complain. You can advocate for your child – up to a point. Beyond that, however, they politely suggest that you consider other school options for your child.

The next time you are seated in first class on a flight somewhere, ask the flight attendant – as I did once – if they know which passengers got their first class seat through a mileage upgrade and which passengers paid full price. The answer came with a knowing glance and a smile, “Oh yes, we know.”

This is the difference between having privilege and being given privilege.

***

They don’t call them “private schools” anymore. The term was abandoned, no longer politically correct. It implied exclusivity. It implied elitism. Of course, even without the old obsolete label, these traits were still entirely true. That was never going to change. But the old label was simply bad for image management in the new millennium, and so it was retired.

Today, “independent schools” are fully committed to the values of diversity and inclusion. Today, it is explicit to their mission to “level the playing field.”

Yes, but we have a different perspective; a point of view borne of our own experiences as young black men attending one of the most prestigious, most exclusive, most “private” schools in the nation.

The playing field is never going to be level.

In this book, Ray and I are going to try to explain that. We’re going to attempt to explain the paradox of how the most prestigious “independent” schools in the country can be so zealously fully committed – simultaneously and concurrently – to both exclusion and inclusion. It’s not hypocrisy and it’s not deceit. It’s paradox; two conflicting realities that are both true. And where else would you expect that to be possible, after all, than in an extraordinary place of privilege?

In the mid-1960’s, for a variety of complex reasons, The Dalton School, and many others like it, chose to be inclusive, chose to admit black boys for the first time. Ray Smaltz and I would not be here, we would not have a story to tell, if not for the fact that Dalton, one of the most elite, expensive private schools in the country invited us in. And once we were in, we were most definitely part of their closed community, a walled garden. It quickly became clear to us that whatever culture we might have brought with us to our new, wealthy white environment, it would be ignored, dismissed or rejected in favor of their own social customs and mores. Our experiences in our own communities, our history, our family upbringings were overwhelmed and overrun (both intentionally and unintentionally) by the Daltonian outlook on life, no matter how unrealistic those options may have been for us. It was up to each and every black and brown student at Dalton and elsewhere at other independent schools to figure out how much we were willing to adapt, assimilate, or transform in order to achieve. Every day that we went to school we found ourselves navigating an elaborate matrix of choices and decisions; when to be like them, when to be like their expectations of us, and when to just be ourselves. Even so, as boys who were just beginning their teenage years, “being ourselves” was a question we were only beginning to work out.

This push and pull of assimilation versus self-actualization had one other critical variable; our families. We were in private school because of our families. Because of our parents. They sent us there. They wanted us there. They invested in us (quite literally) their hopes and dreams that we might have a better life, a better future. Their dream was that the magic of these places of privilege would rub off on us and imbue our lives with great possibilities. They wanted us to succeed in that world, but that meant pushing us away from their world. Although they too were probably conflicted about this impulse, they wanted us to turn our backs on the world we came from.

It was like a struggling mother putting her baby up for adoption so that it could have a better life. In the end, even good intentions and good outcomes leave everyone wounded and damaged.

Bring us in, but keep the essence of us out.

The private school paradox of exclusion and inclusion became like the riddle of the Sphinx. The Sphinx, of course, was the legendary mammoth creature that guarded entrance to the great temples of Egypt (and the city of Thebes, in Greece). All those who failed to answer the riddle correctly were devoured and destroyed. Those who could answer correctly were granted admission. And ironically, the answer to the riddle was a metaphor for how our individual nature changes over time. Some of us understood this. Some of us recognized what was being asked of us. Sadly, Ray and I both bore witness to the crushing defeat of more than a few of our black fellow students who failed to solve the riddle of the Sphinx and did not survive their private school experience.

Does that mean that to survive, and to thrive inside the temple, we must acknowledge and accept the changes imposed upon our individual nature? We’ll see.

We have chosen to use our own experiences and our own stories as a window into a different world, a place that gave us an “education” in the broadest, most transformational meaning of the word. Without diminishing or making less of the abilities that Ray and I already possessed, Dalton gave us tools and perspective that changed the way that we engaged with the world. Sure, we both retained a very strong connection to who and what we were before Dalton. But whether we intended to be or not, Dalton bestowed on us privileges we never imagined and enabled us to plant at least one foot permanently in the world of the ultra-elite.

In New York, the crown jewel place of privilege is The Dalton School; one of the most prestigious, elite prep schools in the nation, recognized globally for its visionary progressive educational philosophy. Whenever popular culture needs a readily recognizable reference for the alma mater of the extraordinarily rich and famous, they simply say “Dalton.” Time Magazine called Dalton “the most progressive of the city's chic schools and the most chic of the city's progressive schools.” Dalton, and the extraordinary places of privilege like it, are where the purebred 1% are taught and groomed to become the next generation of America’s power elite.

Ray and I came to Dalton in the second half of the 1960s. For nearly 50 years, Dalton’s high school had been a very proper – and quite prestigious – school for girls. But now Dalton decided to make the biggest change in its history by embracing – in one sweeping decision – both coeducation and integration. Change seemed to be the only viable choice for the moment. This was, after all, a period of unprecedented, involuntary, wrenching change in America, and few, if any, were optimistic about the outcome of that change. It was a time of omnipresent conflict: young vs. old, black vs. white, north vs. south, haves vs. have-nots. The Civil Rights movement. The Black Power Movement. The Anti-War movement. Everything moving. The assassinations of MLK and RFK led to riots, despair and fear.

It was in this historic, revolutionary time and place that the board of trustees of Dalton felt compelled to reach out to the previously unfamiliar communities of New York and actively recruit minority students. Black boys.

The Dalton trustees committed themselves and their school to a radical course of actions that would not merely embrace change, but would attempt to shape that change into a better, more progressive, more inclusive and more diverse future.

Why did they do it? What was their strategy and what was the benefit they saw? What did the presence of this small group of black boys do to change Dalton forever? …Assuming, of course, that they changed Dalton at all. And what happens to black boys who are placed in this strange new world, without any support system, without any precedent and without any rules of engagement?

It is a long way to look back to the second half of the 1960’s and the first half of the 1970’s. Do any of those memories still matter to anyone? Are the truths that those memories reveal still relevant to anyone? After all, for the young men and women who are in school today, even their parents were probably not yet born when Ray and I were in school. Perhaps our experiences are now nothing more than ancient history.

Or perhaps not.

As part of our research for writing this book, Ray and I interviewed more than 50 other minority students from our era and just as many post-millennial minority students. We spoke with teachers, administrators, parents and a handful of subject matter experts. What we learned was that certain statistical, quantifiable metrics have made enormous progress since our time in school, while certain other metrics appear to be frozen in time from 50 years ago. Why some numbers have changed dramatically, while others haven’t, is not so much a mystery, but more a part of the private school paradox we have only begun to describe.

Has the drive for diversity and inclusion over the past 20 years or so made things any better, or are the ultra-wealthy still gaming the system for their own advantage and privilege? Despite the recent headline-grabbing scandal involving college admissions and the rich and famous, the answer isn’t quite so simple or obvious.

By reaching back into our own experiences and sharing stories, we’ll answer some of these questions. We will offer our own perspective on how attending school in a place of privilege changed our lives, as well as how our presence there changed Dalton and other places like it.

***

The Boycott & The Strike

Before we can talk about our own personal experiences – and why they matter – it is worthwhile to take a moment for a quick review of what was happening in New York City schools in the 1960’s and the inter-relationship (or conflict) between public and private and the dynamic forces that drove them.

In 1954, when the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously to strike down the Jim Crow system of “separate but equal”, it was in a court case about public school education. More than buses or bathrooms or lunch counters, the classroom was the heart of our nation’s segregation. And the classroom was its most toxic factory. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court declared an end to school segregation with the banging of a gavel, but the rest of America soon found out that reality fell far short of the legal ruling. The aftermath of the court decision launched several decades of urban flight; white families avoiding integration and abandoning the crowded cities for suburban sprawl, creating “bedroom communities” and rapidly expanding small towns.

The families that escaped the cities and moved to the suburbs were able to send their children to local public schools where the students were pretty much demographically homogenous, exactly as these parents wanted. All across the country, school district funding in suburban communities is determined by local property taxes. That means that affluent communities – the tony suburbs that surround big cities – are able to endow their local schools with generous budgets so that no legitimate school need goes unmet. Furthermore, these affluent communities benefit from the generosity of well-funded, highly active PTA’s with helicopter stay-at-home moms (or dads) and employers that are happy to match local charitable contributions dollar-for-dollar.

Fairfield County, Connecticut, the home of Greenwich and Westport and my own town of Ridgefield, is also the home of the widest income gap between rich and poor of any county in the nation. Affluent communities stay that way by aggressive political and grass roots lobbying against the threat of “affordable housing” invading their neighborhoods or their school districts. These families don’t worry whether the playing field is ever going to be level. They own the field.

The families that remained in the cities, the affluent urbanites that eschew country and suburban living except on jaunts to their weekend houses upstate, have their own school solution.

Private school.

Northern urban centers like New York City did not have forced segregation backed by Jim Crow laws. The North was supposed to be much more enlightened. Northern cities like New York had “neighborhoods.” They had “ethnic enclaves.” They had ghettos. And in these cities, blacks and whites casually crossed paths on public transportation, at work or even in the department store. There was no “colored section” at the movie theater. In these cities there was the patina of liberal harmony. But in these cities blacks and whites did not live together, they did not worship together, and they did not go to school together.

This last issue – the school issue – was a problem for urban politicians and policy makers. Housing and religion were much tougher to tackle, but with schools, at least they would try. Motivated partly by the legal precedent set by the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, and partly by a progressive political platform, city politicians worked to integrate local school districts. And yet, for a decade after Brown v. Board of Education, their efforts continued to fall very far short of their intended objectives. New York City schools that enrolled mostly black and Latino students tended to have inferior facilities, less experienced teachers and severe overcrowding. Schools in many black and Latino neighborhoods were so overcrowded that they operated on split shifts, with the school day lasting only four hours for students. There could not be any evidence more dramatic of the extent to which minority students were being short-changed and left behind.

What’s it like to study biology from a textbook that never even mentions DNA?

What’s it like to attend a school that has too few school psychologists and counselors – but plenty of in-school police officers?

Once again, education became an effective tool for separating and controlling the destinies of segments of society. This time, instead of separation based upon socio-economic class, the educational divide was along racial lines.

One way or the other, the playing field was never going to be level.

But what if you were rich?

If you are rich, there's no integrated classroom. That world never touched you. If you are rich, you exist in your own solar system, where the planets are Collegiate and Trinity and Horace Mann, Nightingale and Brearley. And Dalton.

Places of privilege.

This is how we got here, the speed-reading version of how we arrived at the world of public and private schools at the time and place when our lives, Ray’s and mine, intersected with Dalton.

Comments

Co-Authors

The co-authors of "Place of Privilege" are Mark Robinson and Raymond Smaltz, III

The book's sub-title is, "Young, Black and in an unexpected place of privilege."

A very niche subject area…

A very niche subject area that has to be accepted at face value. Well-written and highly informative.