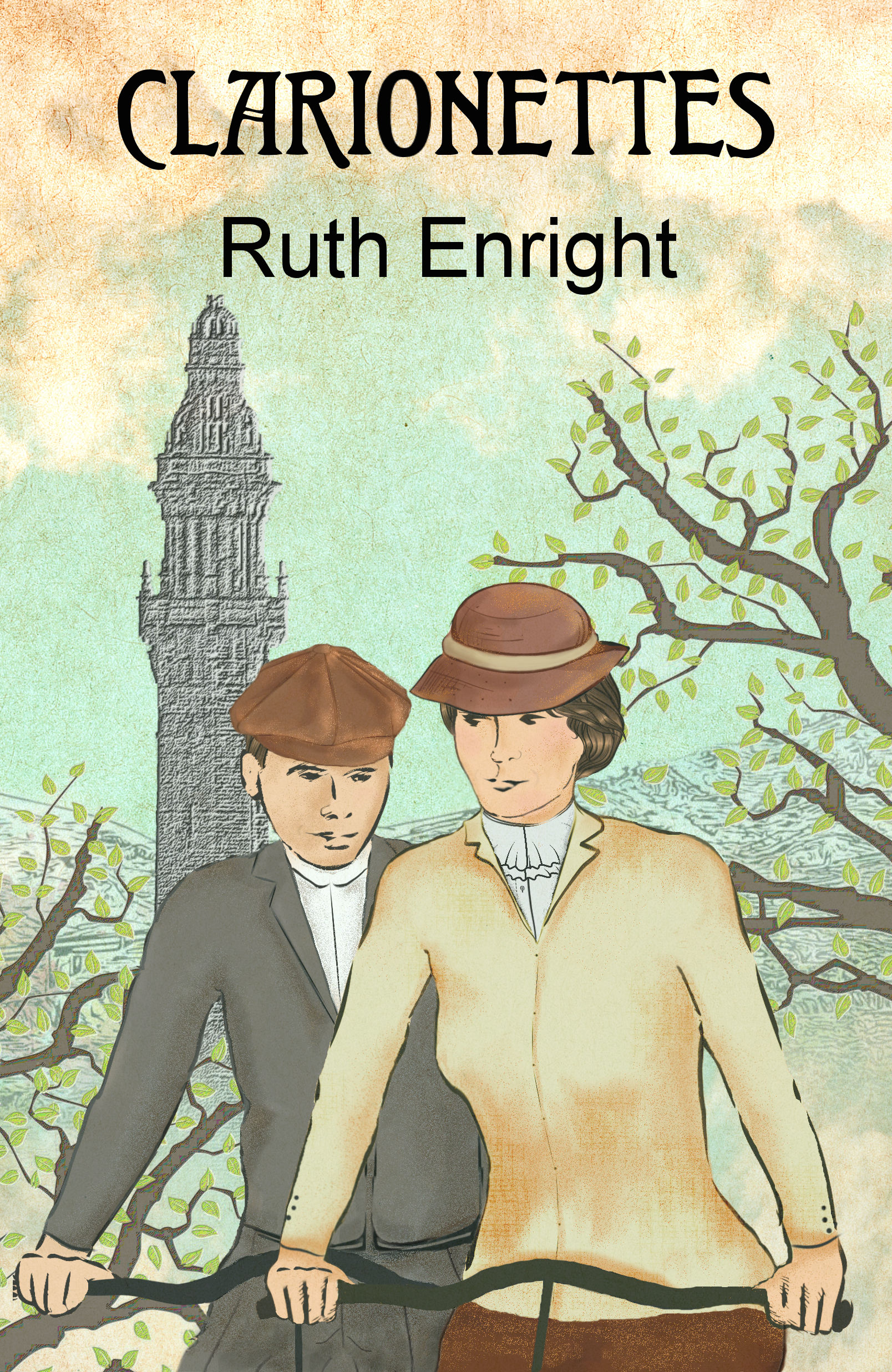

There were twelve of them. Twelve cyclists in the newly established Halifax Clarion Club. Some of them were acquainted already, others only through this fledgling organisation. They were a loose alliance of young people who had come together to combine the pleasures of cycling in the countryside with sharing the Clarion newspaper’s broadly socialist ideas of the day. Published in Bradford by former Halifax man Robert Blatchford, it was the inspiration for all the popular Clarion Cycling Clubs springing up in industrial towns and cities in the last few years. The groups’ members were called ‘Clarionettes’.

It seemed unlikely that socialism, however vaguely conceived, was the reason for some of the people in this group to be there, but the activity was something new and daring which enabled the classes and sexes to mix, and in a physical exercise outdoors which was frowned on by the respectable. For those who did take the club’s founding ethic seriously, the presence of those who did not was going to be irksome, but for the present they were young, new to it and enjoying their first group cycle, men and women together.

The Halifax Clarionettes were mill workers, a minister’s daughter, a teacher at the Crossley and Porter Orphan Home and School, and one or two were even the children of mill owners. Younger sons and daughters, they had some sensibility about how their own prosperity and the reasons for it contrasted with the positions of others. They were possibly freer to consider it, since they would not be the direct inheritors of the family wealth. One of them, however, Noel Ogden, was already a rich heir. Always at the forefront of anything unorthodox and an eccentric individual, he had come into his factory-born money young. He indulged himself in extravagant theatricals and was always busy remodelling his mansion as the fancy took him. His favourite costume, in which he had been photographed, was worn for playing Oberon, King of the Fairies. Dressed in this, he sat in a gilded throne, was much garlanded with flowers for a crown and wore a slashed doublet, silk stockings, fancy buckled shoes and the expression of a poet and aesthete (neither of which he really was).

The Clarionettes had alighted on the top of Albert Promenade, a long pavement on an escarpment with views across the Calder Valley towards the hilly fields of Norland. Trains on the railway line below produced the only smoke in the air, for it being Sunday, the mill chimneys of Halifax, and Sowerby Bridge further along, were not fired up today. Sitting on the black, millstone grit crags, they had paused for their picnic refreshments at lunchtime. Two friends, monumental stonemasons who worked together, were engaged in chiselling their names and the date of this visit into the obdurate dark rock – ‘J.H. Henderson, C.W. Raynor, 1896’ – where they might last as long as the stone and marble memorials they made for the graveyards.

“This is a public promenade, you know, John and Cyril,” said Ellen Rastrick, worried they were transgressing.

Ellen was the youngest daughter of a bobbin factory owner. She was here with her maid, Libby, who was accompanying her on a Sunday off and so could join her privately.

“The rocks don’t belong to anyone, Miss Rastrick,” said John in his loud, cheery voice. “And that wants to be noted down.”

They all laughed, as the group’s secretary would say this of any point of action or particularly meaningful statement made at meetings. Proceedings had to pause while he laboriously did so. George Holroyd had learned to read and write after his retirement from the Pellon Lane Mill and was proud of the achievement, so that the others, respecting this older radical, let him take his time.

The more genteel walkers who were strolling along the promenade today looked askance at this unruly group of cyclists at rest, their bicycles lying beside them in a mechanical heap. Ellen had read about the Clarionettes in the newspaper and talked to Libby of them when she was having her hair dressed for yet another tame neighbourly visit. Together, they had gone to some meetings under the pretext of Ellen being accompanied to one of the charity bazaars, of which there were always many.

***

Libby’s manner outside the house was quite other than it was with her servant’s cap on. There was a subtle lack of deference in it which showed Ellen that she and the family were probably far less respected as the maid’s employers than they thought they were, even if she and Libby were on quite friendly terms at home. It came as something of a surprise to her seventeen-year-old self, for all her egalitarian notions. Libby’s confidence when speaking at a meeting also surprised the slightly younger Ellen, who found herself a bit inhibited by the gatherings and also by the gruff directness of the working people present.

The Clarionettes had formed a club to finance the purchase of bicycles to be shared between those who did not own them. In this way, those who were young ladies could enjoy the participation without being suspected of harbouring dangerous notions about emancipation. Socialism had begun with those who could contribute more to this by doing so, the working members paying a weekly sub to offset the outlay. This in itself formed a bond between them, as did the fact that, in a sense, this was a clandestine expedition for many of them.

Each of the young ladies from the better social classes were supposedly engaged in some other reason for being out and about. For the working people, it was safer not to be too open about it either, as they might be suspected of views leading to subversive activity in the workplace. The shared bicycles were stored in a disused Sunday School building attached to a small Methodist Church, of which the retired group secretary was now the caretaker and graveyard gardener, for a small remuneration. While you could work you did work, the mills not providing any pension and the wages not offering the opportunity for savings.

Among the Clarionettes, the working men and women present had an instant camaraderie which made them more at ease in the company than some of the others, apart from Noel, whom nothing ever did constrain. Sarah Greenwood and Hannah Robertshaw were mill workers together in Dewhirst Dye Works. Their companion, Albert Dewhirst, was a son of its owner. There was an underlying familiarity between the trio which puzzled Ellen and Jane. Jane Ellison was a minister’s daughter and, like Ellen, had little notion of what that familiarity might be. Albert was turning Sarah and Hannah about in different positions on the rocks, saying they would make a tableau in his photographic studio and he would picture them as nymphs in the woods of holm oaks growing on the slopes below.

“Or, I could set up my box camera and picture you here in situ,” he said. “We can return one private afternoon, the three of us.”

“Do tell us more of that, Albert,” said Ellen, overhearing him. “I should like my portrait taken with a bicycle. Mother would be pleased,” she added jestingly.

The two mill women exchanged an amused look, again suggestive of secrets between them and a little mocking of Ellen’s naivety, but Albert raised his hat and said, to a ripple of laughter from them all, “I should be delighted, Miss Rastrick. I am only an amateur, though, and would probably fail to do you justice.”

Noel jumped in to call across, “Albert, I would be happy to pose for you in any attire or disarray you care for! I hear you have a penchant for the inner chimney sweep in us all and especially in your portraits of the ladies in their native dirt!”

This arch and outrageous statement made Hannah and Sarah smile at one another again. Before Albert could retort, however, attention was distracted by Peter Lumb, who was returning from a short leg stretcher along the promenade, loudly pointing out the lantern-topped pinnacle of Wainhouse Tower to them all.

“Look at that!” he derided. “For summat that never needed building and all for spending money on nowt. Two hundred and fifty-three foot of a mill chimney what never were a mill chimney and now stands there like a stick of rhubarb for all the world to see.”

“Oh, no, I disagree,” said Noel. “There is every need for a folly in this dismally pragmatic world here.”

“Nay. Money squandered, I say,” grumbled Peter, who was feeling these things particularly since, as everyone present knew, he was out of work recently because the flour mill he worked in had burned down after a fire in the drying room.

“You should come in with me,” his friend Stanley Jagger said now, and not for the first time that day or previously. “Crossley Carpets are manufacturing for all over the world. And they do some good, don’t they? The orphanage they built, and the land given for the Moor Field below it to make clean air and a green space for the public choked with smoke?”

“They do, Stanley,” said Eustace Horsfall with a smile. A quiet man who took life seriously, he taught in the orphanage residential school and was particularly wary of Noel Ogden and his dilettante ways.

“What? Work on those looms? I’d be as deaf at twenty as you are, cloth ears!” joked Peter to Stanley.

“Cheeky beggar!” reposted Stanley.

“Besides,” Peter went on indignantly, “Dean Clough Mills are t’ only ones won’t go for that new four day August break t’ Chamber of Commerce ’ave just agreed for mill workers every year. Ah’m not working theer!”

“Wakes week, you mean,” countered Stanley with a grin.

Peter rose inevitably to the bait with, “Nay, that’s for Lancashire’s mill folk. We want a proper good Yorkshire name for ours!”

Desultory cheers and ironic clapping met this truculent statement. Although they were still in high feather about such a watermark concession by the employers, it was a Clarion Club campaign to press for this holiday, so recently won, to have a title fitting for its locality. So far, however, it was still going to be ‘Wakes Week’.

“Why not ‘Wainhouse Week’?” suggested Noel flippantly, pointing up at the tower which had been the subject of Peter’s strident objections. “Did you know that several parties who set out to mount to the top of that tower were never seen again? Its central staircase winds and winds in the dark with only a slit window here and there to let in the light of the world and you lose your way. It’s like a maze in there.”

“Rubbish, Noel,” said Albert trenchantly. He knew Noel well and had no scruple about giving the lie to his romancing. “It was built for a dye works chimney over twenty years back. My father often tells the story of Wainhouse and Henry Edwards coming to daggers drawn about it. Edwards boasting nothing would dominate the landscape like his mansion at Pye Nest and Wainright swearing down that Edwards would have no option but to look out at his chimney every morning from his windows.”

“I know why it was built, Albert. A great notion for a factory chimney,” said Noel.

“Aye but it were never finished as that or used as one,” said Peter in his dour manner, churlish about it as an excess to be disapproved of, which was rather how he viewed Noel himself. “And when the dye works was sold, that monstrosity was left out of the purchase. They say it will be sold off again soon to a private owner but I don’t know who’d want it.”

“I want to have it,” declared Noel flippantly. “I can grow my hair long and lean over the balcony at the top like Rapunzel. Which of you would climb up to rescue me? You can bring the Neptune fire engine from Victoria Mill with its ladders, gentlemen.”

“Not I!” said Peter hotly, disgusted by this effete talk and looking rather aggressive. “We’re not ’ere to listen to daft prattle from t’ like of thee about summat serious!”

Peter Lumb, John Henderson and Cyril Raynor were all volunteer firemen and there were plenty of blazes for them to attend in the area, brave and risky affairs. Noel’s flippancy about that clearly offended him too.

“I thought we were all friends together here, Peter,” laughed Noel, pleased to have nettled him because he had that kind of sly, puckish humour.

“I think you would look beautiful, Noel,” said Ellen, who admired Noel very much and was envious of his carefree flouting of conventions.

“I would, Ellen,” replied Noel complacently. “With a cascade of this grown rippling down the wall for some strong young man to climb up and get me. Can you imagine?”

He ruffled at his loose ringlets of dark gold, fondling them in a satirical way that made the other young men look at one another and laugh, for in spite of his words and posturing there was nothing particularly effeminate about Noel’s manner or voice, although he wore his hair longer than they did and dressed for effect wherever possible. He was a tall, athletic young man who might easily become burly from self-indulgent living if he did not exercise as fanatically as he did everything else, while the fad lasted. For the present, it was the Clarionettes and cycling. He wanted the company, liked the frisson of mingling with the lower orders and enjoyed any opportunity to shock or irritate.

“I may try to find out who owns it now and put in an offer for it,” he went on. “We can climb to the top and halloo all below to our hearts’ content. Do you know that it has four hundred and three stone steps in its circular staircase inside?”

“Oh, do buy it, Noel! I think it’s a marvellous idea,” said Ellen.

“Hardly a contribution to the Clarion Club though, Miss Ellen, is it?” said Libby, crushing Ellen’s enthusiasm as Libby liked to do when they were among this group. Besides, Ellen’s clear admiration of Noel Ogden was a gauche thing and flattered his considerable vanity. “I don’t know so much about photographs of nymphs either, Albert,” she said, but when she spoke to Albert it was in a lighter way because he was handsome and she liked him. “We are all comrades together in the Clarion Club, aren’t we? Real people. Men and women together.”

“That’s true,” he conceded. “And it is how I like it. Men and women together.” He met her eyes flirtatiously with his own, rather fine, dark ones and flashed a grin of his even white teeth (a rarity in that area). “But it does not prevent us aspiring to art. If you were to be a nymph, Libby, you would bring some sense into the proceedings, I’m sure.”

“I am sure I would,” she agreed.

Hannah Robertshaw and Sarah Greenwood exchanged that private look, with another of those conspiratorial smiles, which suggested their own connection with Albert outweighed any other flirtation. Libby felt this and eyed them with disfavour.

“Look. There’s grass growing all over them ’ills opposite,” remarked Stanley Jagger. “On Beacon Hill behind Dean Clough Mills it’s black as soot all t’ way up and not a twig or leaf anywhere on it!”

“We must get more of your fellows to join us!” said Jane. “Feel how sweet the breeze is up here and how fresh the air is to breathe!”

“You could be preaching that in your father’s Sunday School instead of being out with us enjoying yourself, Jane,” said Noel, with a teasing smile which did not take the sting out of his words.

Jane flushed, sensitive to being found priggish, moving Eustace Horsfall to say, “I think it’s a fine sentiment, Miss Ellison, Jane, I should say, and very well said.”

“Here, here,” said John Henderson in his deep voice and he stood up to invite Jane to look at the inscription he and Cyril had made. “Take my hand over the wall there” – (a low wall edged the pavement) – “and see this view below, Jane. It is even finer from this escarpment. There’s a narrow way to climb down the rocks too if we dared it one day with a rope, Cyril. Good practice for our drills.”

Jane accepted, grateful to be saved from a reply, for she never knew how to parry Noel’s little sallies. She and the two men peered down the twisting break between the rocks forming a narrow, dark column to be squeezed through. John and Cyril discussed climbing up and down the tall rock face with grappling irons and ropes as training for their firemen’s duties.

“We should produce leaflets,” said Eustace to the others, “to give out in the mills you all work in. Invite people to join us as Jane suggested.”

“Like I said at t’ meeting, Eustace, most folk can’t read, so there’s no point in that,” answered Peter Lumb in his downright fashion, always ready with a reason why not before he found a reason to agree to something.

“No,” said Eustace, blushing but pressing on. “Although we can speak to people outside when they leave the workplace perhaps? And we should try to offer them a chance to learn to read.”

“You could, Eustace, and Albert and even Noel over there. Some of the ladies might. Not us working men and keep our jobs.”

It was a circular discussion but Eustace, being the dogged sort, kept coming back to his point when the opportunity offered. Noel had languidly got up and stepped over the wall to look at the view too and, with him out of earshot, Peter said, “If we’d known that great ninny would inflict himself on us like this so much, we’d never have agreed to Albert there inviting him in, would we?”

Comments

I feel sure this would be…

I feel sure this would be far better without all the lengthy exposition at the beginning. Try to 'activate' the characters sooner within the setting and allow them to show us what's going on.