Cleave (intransitive verb): to adhere firmly, closely, loyally and unwaveringly,

Cleave (transitive verb): to split forcefully, to separate into distinct parts, and especially into groups having divergent views.

Contronym: a word that has two meanings that contradict one another.

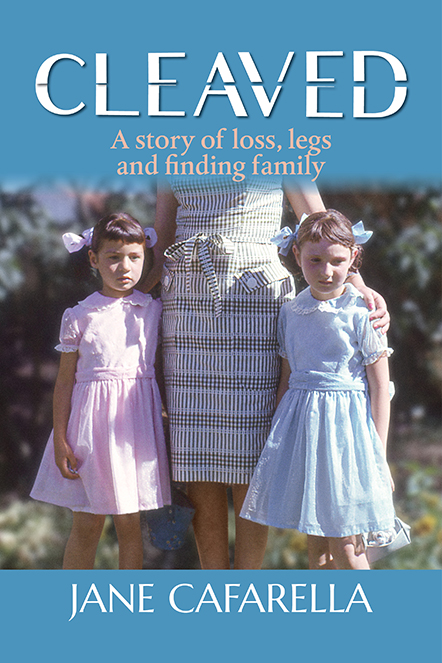

Me at age 13 in high school. This was the last photo I allowed that showed my leg. I soon learned to sit at the back. Later, as it worsened, I wore long dresses or flares to hide it.

PART ONE

Cleaving

1

The jagged nail on the ring finger of my left hand is proof that my sister Julie hates me, or so my mother tells me.

“You were just a baby,” she says, puffing on her cigarette. “We were living in Croydon. I heard you crying and found you sitting up in the pram with blood all over your hand. You’d been sitting with your fingers on the edge of the pram when Julie brought the hood down on them.

“Your father was at work. Croydon was just the sticks then. I had no car and no phone. I gathered you up and started running, running, running, with Julie clinging to my skirts, across the paddocks to the neighbour’s house to call the doctor,” she says, panting in recollection.

Instinctively, I curl my fingers into my palm and examine my nail, painted pearly pink, and the scar, barely detectable now, where the dangling finger was sewn back.

“She’s perverse,” my mother says, reaching for the sherry bottle and pouring a preparatory glass – Three Roses, her favourite.

I am 17. I sit opposite on a kitchen chair across the wobbly card table in our tiny flat with its big square window, masked by a squinting venetian blind drawn against the cold of a winter evening. She is 47. Her dark wispy hair is drawn back from her long pale face in a bun.

Parkdale, 1974

3

Her skin is still smooth but her full mouth is empty of smiles. She wears no make-up, except for red lipstick, transferred to the filter of the cigarette she holds. There’s no one to impress except me, and I’m already on her side.

The story of the pram and the blood is the sequel to the main story, which I know is next – of how my sister and I were separated at birth, although we grew up in the same house.

My mother sips and sighs and begins to speak in the low seductive voice of a seasoned storyteller, the voice of a singer who has been trained and whose words carry across rooms and decades.

I don’t listen. I don’t have to. Like all her stories, I know this one by heart.

** *

1956

It was a cold winter day in July. My mother lay in the hospital bed next to my sister’s crib. It had been a difficult birth. Her first pregnancy had been ectopic – the foetus aborting after implanting in the fallopian tube. By the time this second pregnancy reached full term her Rh- negative Rhesus “monkey blood”, as she called it, had developed a battalion of antibodies, poisoning my sister’s Rh-positive blood and turning her into a “blue baby”. A blood transfusion saved her life. Shocked and exhausted, my mother lay waiting to be comforted and consoled. But the new father wasn’t interested in the new mother.

“He walked straight past me to the crib and picked her up, and I thought, she’s his,” she tells me, describing again how she and my father sealed my sister’s fate.

The only claim my mother makes to the child is to name her Juliana Sophia, after her maternal great grandmother, who is of Danish heritage. The beautiful musical name, the perfect accompani- ment to Cafarella – my father’s Italian surname – is recorded on the baptism certificate, but at home she is just Julie, the child of the father who claims her and renames her.

4

Fourteen months later, I am born – six weeks early, as the battalion of antibodies in my mother’s blood has become an army.

“You were two pounds and the colour of that table,” she tells me every birthday, pointing to our mahogany dining table. I am transfused twice. My lungs are as tiny and fragile as butterfly wings. There are no guarantees, the doctor says. A priest is summoned, along with a miracle. When it’s granted, I am the child my mother claims.

“I cleaved you to me. I grabbed you up, because you were a very ill baby,” she tells me as the years roll by, her jade eyes wide. “I was around you all the time, weeping and crying. Around you all the time, stuck to you like glue.”

And the story of our cleaving feels both inevitable and uncomfort- able, a fairy tale curse – and a gift.

She names me Jane Louise after her father Lewis and his mother Jane. Yorkshire pudding followed by Spaghetti Bolognese. Unmusical. My father doesn’t comment.

Not long after my severed finger heals, I am crawling around the floor of the doctor’s office where Mum has taken me for my check-up.

“Notice anything about her?” the doctor says. “Yes,” Mum says. “She’s beautiful.”

“What else?” asks the doctor.

“Nothing else.”

“Look at her legs.”

“What about them?”

“One is bigger.”

My right leg, from calf to foot, is indeed slightly bigger than the

left. Mum also suffers from puffy feet. But this is different. It never goes down. There’s no name and no treatment, the doctor says. I am just born that way, so it’s ignored. I can walk, and run, although over the years, it gets bigger and my foot prickles and aches and swells further in the heat, spilling over the edges of my shoe like a cake baked in a tin that’s too small. My mother cleaves me further, and the chasm between my sister and me grows a little wider.

5

The black-and-white photo of Julie aged three standing in Dad’s work boots is proof of our allegiances. She wears baggy overalls and an unflattering pudding-bowl haircut, accentuating her broad face and wide-spaced amber-green eyes, a darker shade of Mum’s. Her hair is brown and her skin is fair like Mum’s, while I have Dad’s olive skin and the dark eyes of the grandfather I am named after. My hair is dark and wispy like Mum’s, except mine forms floppy curls. Mum licks her finger and twists the curls around it to make them stick.

** *

While Dad is focused on getting rich in the milk bar business, Mum makes us her projects. She dubs me Pebble-head, for my oval face, and Julie Pumpkin-top, for her round face, and pins tiny cotton bags containing camphor squares to our singlets, to ward off colds. She dresses us in the little cotton pinafores that her mother, Nanny, makes, with matching ribbons in our hair.

“You had little brown boots that I polished till they shone,” she tells me, except where Julie has one pair I have two for my mismatched feet.

She saves up for a double pusher with a fringe of pompoms around the hood, and pushes us triumphantly down the street, the little blue babies who are now pink and bonny (or in my case, brown): testament to her struggle and sacrifice. “Are they twins?” strangers gush, although anyone can see we’re not. We are too different.

I am three and Julie is four when Perry, Dad’s partner in the milk bar business, is jailed for fraud, although I am never told Perry’s full name or what sort of fraud he committed. Unable to pay his debts, Dad is declared bankrupt, though Mum says he probably could have managed that all by himself.

“He used to lock all the bills in the desk and refuse to open them,” she says.

The stench of shame follows us a year later when we move from “the sticks” in Croydon to a three-bedroom weatherboard house in

6

Remo Street, in the bayside suburb of Mentone. Our house in Remo Street is a short walk from Nanny and Pa’s house in Florence Street, and Dad’s sister Mary in Balcombe Road, where the conversations are peppered with Sicilian dialect, which everybody understands except Mum, Julie and me. Like Mentone, where all the main streets are named after Italian towns and

and cities, we are fake Italians in fake Italy.

“Can we swing on your muscles?” Julie says, skipping towards Dad as he walks towards us along Mentone Parade one summer evening on the way home from work, his brown shoulders bare under the loose bib of his paint-spattered blue overalls. He puts his hands behind his head, flexing his muscles until they form hard hills. Julie hangs on, but I hang back. Though she’s a year older, she is lighter, as my leg weighs heavy. Encouraged by Mum, I join her and the smell of putty, paint, motor oil, cigarettes and PK chewing gum greets me as I lift my legs and swing briefly, before Dad drops his arms.

Today he is a spray painter, with rags streaked with pink putty poking from his pockets. Sometimes he’s a welder, and his bright blue eyes are red from the bits of metal that fly into them. Sometimes, he works nightshift in a factory as a fitter and turner, although I don’t know what he fits or turns. Sometimes he is a salesman, with slicked back hair, the fresh citrus smell of Old Spice aftershave masking his morning cigarette as he squeezes his thin black socks over the wire coat hangers he has moulded into sausage shapes, and lays them on the old green enamel Kookaburra wood fire stove to dry.

But to Mum he’s just a fool.

“He can never stick at anything. He always thinks he knows better than the boss,” she says, her mouth grim. He’s also “uncouth”, which means he has no manners.

“He’s like a horse that’s been let out of the stable,” she says, as he ambles down the hallway in his singlet and blue shorts, farting noisily, and disappears outside to the toilet, where he keeps his stack of Popular Mechanics, his favourite magazine.

Inspired, he sketches plans on the cream laminate top of our kitchen table with the mechanical pencil he keeps in his top pocket

7

and which never needs sharpening. His hands like all the Cafarellas, are long-fingered and finely boned, with fine blue veins forming rivers and tributaries across his smooth brown skin. His bare brown legs are splayed, and his bare feet in worn rubber thongs, reveal his “hammer toes” – the little toe crossed over the fourth, as if hammered on. Every now and again, he stops sketching and cuts thick slabs of butter, which he plasters on his favourite square Uneeda biscuits, slurping noisily as he dips them in his tea, where the butter forms oily pools.

“How to mould character into drab walls,” advises Popular Mechanics, and egged on by Mum, Dad replaces the wall between our dining room and lounge room with an archway covered in thick swirls of white paint, Spanish style. Dad is going to make us a steel- framed garage too, but as winter approaches, the concrete slab fills with puddles and the four fat poles he plants at the corners become thick with orange rust, matching Mum’s orange mohair cardigan, which like all our clothes, comes from the SOS op shop.

When our friend Nita Lund complains she is too old and puffed to walk the length of the golf course, Dad sketches plans for a golf buggy and soon fashions a chair from sheet metal, with a square orange plastic cushion that slots neatly into the space he has cut for it. The golf buggy is powered by a two-stroke engine with a joystick to steer it. Julie sits on Dad’s knee and I stand on the platform at the back where Nita Lund will put her golf clubs, and we chug along to Nanny’s house in Florence Street. Sometimes Julie and I take the golf buggy out on our own, until one day it topples over and burns Julie’s shoulder and Mum bans us. When it’s finished, Dad sprays it mint green, to contrast with the orange cushion, but Nita Lund never uses it. It’s too noisy.

It’s Mum who makes us a desk from an old door she paints sky blue and rests on two towers of old bricks, where we sit cutting pictures from magazines and pasting them in our scrap books. On wet days, she lines the wide hallway with her cake tins and baking trays, and the metallic pings turn to soft plops as the tins fill up.

8

“I’m sick of living off the smell of an oily rag surrounded by crap,” she says gazing through the kitchen window at our back yard with its mass of weeds that reach out to choke the few shrubs that dare to survive. Giant wooden cable reels serve as tables, but we don’t sit there. The yard is too littered with old car parts, chicken wire, hessian bags, and bits of wood with nails sticking up that twice result in tetanus injections for me.

On a good day she calls him “the pot and pan”, rhyming slang for “the old man”, and he calls her “wifey”, and he nips into the kitchen to whip up a cake for friends – a hangover from his days as an apprentice pastry cook – serving it with ambrosial charm.

On a good day, they play and sing together.

“Bring the guitar,” friends plead and Dad throws it in the back of his car with its mess of tools. Dad sings harmony to her melody, in songs that seem to parallel their lives – The Sweetheart Tree, about the tree that bursts into bloom when true lovers carve their name in it, Lemon Tree, when love turns sour, and Single Girl – about the mother who rocks the cradle and cries for the days when she was single and free.

Singing is both a blessing and a curse in our family. Everybody does it – except Mum’s sister Doris, whom we call Dottie. Nana Cafarella’s mother even died of it after a jealous woman cast the evil eye on her, leaving Nana motherless at just 14 months of age. But nobody can sing like Mum.

My mother’s voice is the soundtrack of my childhood. A beauti- ful effortless soprano, it soars over the clash of dishes, the hum of vacuum cleaners and the relentless pleading of “But Frank ...” as my father flees her scalding tongue.

She spurns the school mothers’ club and the fundraising white elephant and cake stalls. Instead, she holds a musical evening at our house in Remo Street, with herself in the starring role of Madam Butterfly, complete with kimono and white face make-up, a rosebud of lipstick centred on her full lips and two knitting needles poking out at right angles from her cobwebby “comb-up”.

9

“The cars were parked all down the street,” she says.

She forms a little performing group with two friends. Mum sings all the big numbers – Velia, the Witch of the Wood, from The Merry Widow, This is My Beloved, from Kismet and Gounod’s (and only Gounod’s) Ave Maria. For comic relief, she sings Big Spender, and Second Hand Rose, finishing with a duet of Wish Me Luck As You Wave Me Goodbye.

There is never enough of this singing for Julie and me. We crave it like sugar and can repeat all the words of the songs like prayers. Once, when Nanny takes us to visit her older brother Uncle Tom, we entertain them, piping away in imitation of our parents, enjoying the way our voices blend. We sing melody, but just like Mum and Dad we are in perfect harmony.

But not for long. On a bad day, he calls her “face-ache” and she calls him “a fool” and “a no-hoper”. On the worst days, she follows him from room to room, pleading “But Frank ...” as he flees her accusations about the neglected house and the neglected bills, slamming every door in her face until the final slamming of the car door, as he roars off to his friend Jeff or to his big sister Aunty Mary, who calls him “Poor Frankie”, for having a wife as useless and unsympathetic as my mother. Sometimes he takes my sister Julie with him.

I follow my mother to the red phone box at the end of the street, where I sit underneath the tall bench, while she talks in a low urgent voice to Nanny or her sister Doris, until there is an impatient rap on the glass, and she says, “I have to go. Someone wants the phone.”

“And another thing,” Mum says as soon as Dad returns with Julie. And another and another, until he flees again, or on Sundays, retreats to the lounge room to watch “the fight of the century” on World Championship Wrestling, where compere Jack Little tells him in a gravelly Southern drawl, “Neither one will give an inch.”

Comments

It's very rare for me to…

It's very rare for me to feel I have to read anything right until the inal full stop but this is so good I really didn't have a choice. Whatever the genre, the devil's always in the detail; never more so than in a memoir. The second challenge is how to tell a very personal story without boring the underwear off everyone. And, of course, that's where the writer's craft comes into play. Not a word is wasted; not a single opportunity missed to create the most vivid of pictures via all of our senses. Add to this a wicked sense of humour and a joie de vivre that is dangerously infectious, and that sums up 'Cleaved' pretty well. It's one of those occasions when you feel seriously pissed off that you hadn't written it yourself. The only question it doesn't answer is this: why in all that's good and holy has this not been taken up by a mainstream publisher?

Though simplistic and to the…

Though simplistic and to the point, the writing carries a hauntingly captivating quality. Love the use of the word "Cleaved". However, just one note. I would suggest you reconsider your subtitle: A story of loss, legs and finding family. Not only it is not immediately clear what that means and seems fragmented, it is also a bit difficult to remember and repeat.

There are great descriptions…

There are great descriptions in this, and it's a good beginning!