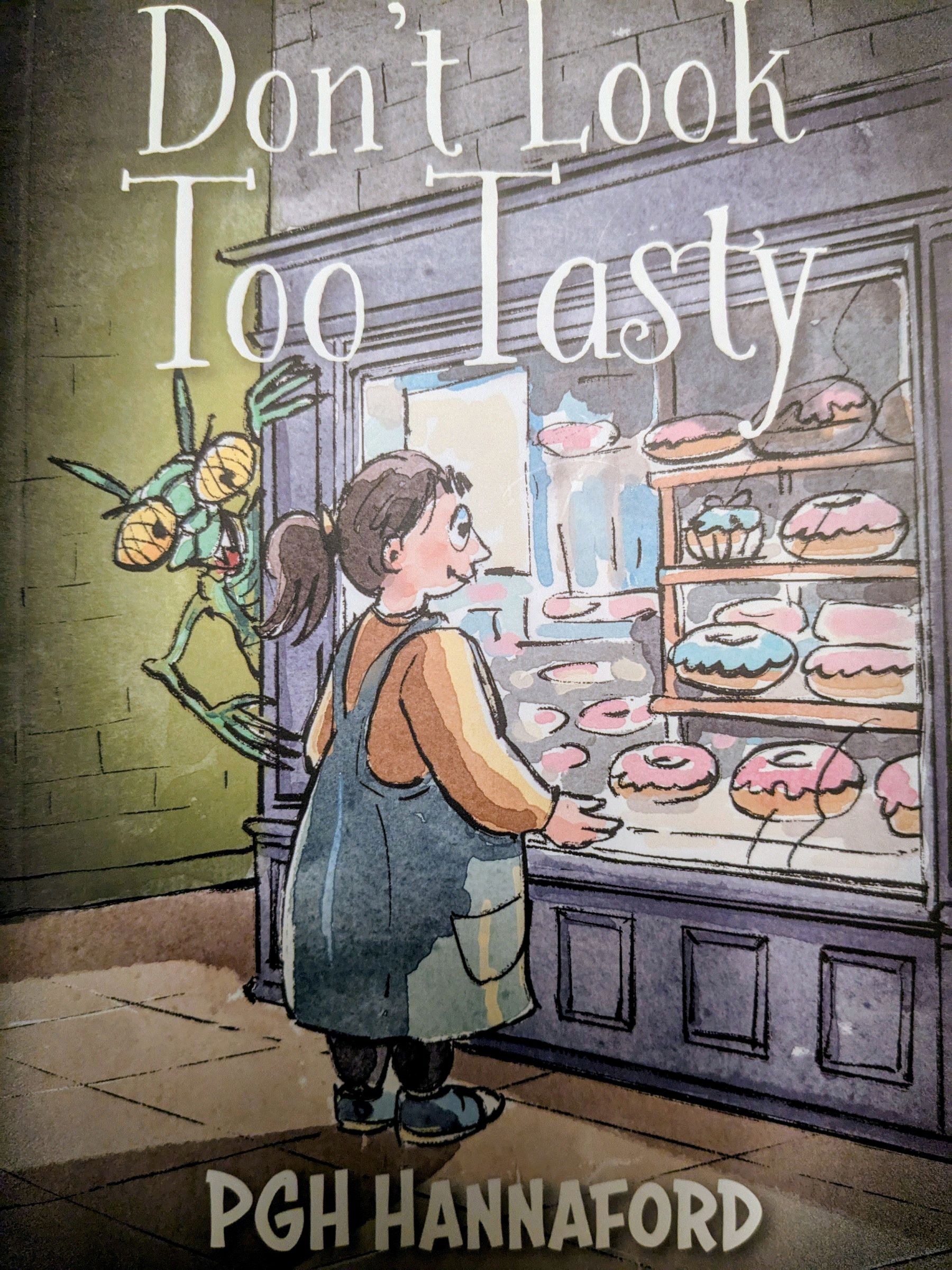

DON’T LOOK TOO TASTY

Introduction

Here’s the thing: I no longer know what day it is. I often don’t know where I am, but lately I’ve been trying to make sense of it all. I found this manuscript the other day, in an old biscuit tin under my bed, along with some chocolate digestives and half a packet of Jaffa Cakes. I don’t know what it was doing there. I don’t know why there would be biscuits under my bed. Who does that?

The manuscript was in my hand writing, and I remember a lot of what’s in it, but I don’t remember actually writing it. There were a couple of sketches too; the type of thing I did in my ‘comic-book’ phase. Maybe I kept a journal or a diary. I mean it looks like I wrote this as a memory, so maybe I haven’t caught up with that part of my life yet.

PART ONE

Mr Newton

Chapter One

It all started when Mum and Dad made me move schools. I didn’t want to, but Dad had gone crazy – well he’d stopped going to work after that incident when he punched the window-cleaner guy. Mum had gone back to work when she didn’t want to and we’d had to move towns. So, I was at a new school.

“Hi … I’m Elemenope.” The little red-haired girl stuck out her hand like a businessman on the telly.

“Hi Penelope. I’m Martha Gibbons.”

“I know. My mum said to look out for you. But my name’s Elemenope.” She was whispering. Was her name a secret?

“That’s what I said … Penelope.”

She shook her head and said, “Everybody does that. I don’t know why; it’s a perfectly understandable name. It’s the letters of the alphabet; you know … LMNOP.”

I said, “Oh … sorry … I get it now.” I still had to think about it.

“Liquorice all sort?” I asked her, holding out the bag I’d smuggled out of the house. There weren’t many left, but I thought it was polite to ask anyway. I’d eaten most of them on the way to school, while Mum ranted on about how I was going to love my new school, and not letting me speak so I could munch away without getting caught.

“No thanks, Martha. I don’t eat sweets before lunch-time.”

“Suit yourself.” I thought, ‘there won’t be any left by then!’

Mum was doing her fake ‘everything’s-going-to-be-OK’ smile. She was talking to a big version of Elemenope and they were both nodding in our direction.

Elemenope said, “I’m supposed to take you under my wing, like a mother hen.”

I snorted. Elemenope was freckly, with great waves of really red hair, and I could imagine her as a hen. The problem was her size: barely half mine.

“Come on, Martha,” whispered Elemenope, “I’ll show you where the lockers are.” I didn’t know it at first, but Elemenope whispered all the time; like she was telling a secret, and that was a problem, because I couldn’t tell whether she was or wasn’t. I had to put it in context. Obviously, the location of the toilets was not a secret (that would be weird), but when she told me about taking money from her Mum’s purse, well surely that was a secret. Tricky.

Elemenope showed me a two-pound coin and said, “We can share something at the tuck-shop. They do cream buns.”

My mouth watered. I said, “My old school didn’t have a tuck-shop.”

She said, “There isn’t usually one here either; it’s just for this week … some kind of fund-raiser. Mum doesn’t approve, so I took this from her purse when she wasn’t looking.”

“My mum’s the same. She’d give me another fat-girl lecture and I’d just go hungry.”

If Elemenope said anything I couldn’t have heard it over the clanging of Big Ben. There was a really tall, ridiculously skinny, lady in a long dress heaving an old-fashioned brass bell. Her face was a triangle of red fury. Elemenope grabbed my hand and pulled me to a group of kids, starting to form a line.

“What’s going on?” I realised the whole school was doing this. There were six neat lines and all sound had stopped; nobody was talking any more.

Elemenope shook her head at me and whispered behind her hand, “That’s Mrs Gnash … stay out of her way. She’s horrible.”

We started to march – well the other kids did – I tried to copy them. I tried again to ask Elemenope what this was all about, but she put a finger to her lips and shook her head. I glanced at the lady in the long dress as I walked past, trying to keep in step; she looked like the statue of liberty’s ugly sister. Her huge eyes followed me. I felt like a slice of pizza must feel before it gets eaten.

I looked away. I tried to be a robot, but that made me slow down and I felt a shoe kick at my right heel. It was the boy behind me. Was he doing this deliberately? Was he one of those kids? I turned around and saw his face, rigid with fear. His eyes stared straight ahead as he focused on walking in a straight line.

I stopped, so he walked right into me. That made the kids behind him walk into him, and then there was a pile-up. It was my fault, I knew, but it was all so unexpected. All that discipline was just not normal.

The tangle of frightened kids happened right at the doorway into the long school corridor. Why were they frightened? They should all have been laughing. Then I heard the whistle and the statue of liberty was in my face.

“Who is this new, large, child?” Her voice made me think of insects. I couldn’t speak, but I couldn’t help staring at her. Her eyebrows wriggled like they had a life of their own. She thrust her triangular face further into mine … phew! Her breath stank. No wonder everybody was scared of her.

Slowly we all got up off the ground, out of each other’s legs and faces. The line reformed and we marched into our classroom. That’s when I saw him for the first time; at least I thought it was a him.

Chapter Two

It was bad enough having to start at a new school with new kids, new teachers, new toilets, new rules. It was a long list of new. But nobody, old or new, could ever have expected Mr Newton.

He was standing at the front of the classroom, to the side of the desk, staring at us. Was he staring? How could I tell? His face was all wrong. It was a mask, and he was wearing a hat – indoors. Elemenope took my hand and whispered, “Don’t stare; that’s Mr Newton. Don’t stare at Mr Newton.”

Just as we settled in, there was a breathy sound, like a loudspeaker crackling, then a voice said, “Good morning children. Welcome to class five … we’re going to have a great year.” I looked for the speaker, but I couldn’t see one.

Elemenope whispered, “That’s his voice. Weird, right?”

I listened hard to the sounds that made up Mr Newton’s voice. I’d heard something like it before. Then it hit me: Stephen Hawking. Dad was watching a documentary a little while ago, and this man in a wheelchair was using a machine to talk for him; it sounded exactly like Mr Newton’s voice. So, I knew it wasn’t his real voice. I had to try really hard not to stare; it was way too strange.

Mr Newton, or rather his voice machine, told us about the daily routine: we would have a school assembly and a separate class assembly. There was a time slot for English and one for maths. I was resigning myself to just another boring school year when he said something about ancient Egypt; that sounded remotely interesting. And there was this new thing called ‘rainbow maths’, which sounded terrible.

“Let’s get off to a rocket-propelled start,” said the machine voice. It seemed strangely apt. “A rapid-fire maths test to sweep away the holidays.”

I groaned out loud. Mr Newton, who was looking over me to a chart on the back wall, slowly tilted his head so he was looking straight at me. I couldn’t look away. The mask was rigid; I had no idea what it was made of. Plastic maybe, but it was a really good skin colour. It was too perfect; there were no spots or marks. And it was smooth, like a doll’s face, not rough and scratchy like my dad’s.

The voice said, “Martha Gibbons, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mr Newton,” I squeaked.

“Well, Martha Gibbons, it looks like you get to go first.”

Normally, when an adult spoke to me, I could pick up clues, which was good because I couldn’t always trust the words. There was the facial expression: maybe their eyes didn’t agree with their mouth. And the tone: friendly, critical, angry. I couldn’t tell what was going on, because the machine just sounded the same. Was I in trouble, or was he teasing me?

“Six times seven?”

I was blank; I couldn’t think; I started to sweat. He started to tap his gloved fingers on the table.

“Fifty-six.” I knew it was wrong.

Mr Newton didn’t blink. How could he? His eyes seemed to be swimming behind the mask. He pointed to my left. Elemenope said, “Forty-two”.

He kept pointing at her and said, “Seven eights?”

“Fifty-six,” she whispered.

He didn’t respond. He pointed to a boy in the back row, as he said, “Nine nines?”

“Eighty-one,” yelled the boy.

Mr Newton changed hands and pointed to another boy, “Six sixes?”

That boy yelled too, “Thirty-six.” It went on and on. He pointed at every kid in the class. Sometimes they got two questions in a row. I couldn’t see any pattern to it, but my heart was beating so hard I could hear it in my head. I knew all my times-tables; we did them to death at my old school. So why couldn’t I remember them? I sat still, terrified of another question.

Suddenly it was over; the noise had stopped. I realised my eyes were screwed shut. It was too quiet. When I opened my eyes, Mr Newton was nowhere to be seen. Just as I started to relax, I felt a cold, leathery finger touch the top of my head. It felt wet. Three gentle taps in time to the machine words, “So you see …” I froze. “… Martha Gibbons, it’s very straightforward in this class. I teach – you learn. I ask – you answer. Simple.”

I wished it was a normal voice. I really wanted to think he was just teasing, but I couldn’t tell.

As Mr Newton walked back behind his desk, his legs, or at least his baggy trousers, seemed to be out of time with his feet. I must have been hallucinating with fear and confusion.

“Did you see that? Tell me you saw that.” It was the loudest whisper yet from Elemenope.

“What?”

“That … didn’t you see it? He pulled his watch out of his pocket, but his hands are still on the desk. How did he do that?”

I was sure I was going to be sick. I couldn’t answer. I put my hand up and asked if I could get a drink of water. Mr Newton pointed at the door and said, ‘First right, ten yards, second left … enjoy, Martha Gibbons … water is important.’

The first day of school is universally horrible. It doesn’t matter if it’s your old school and a new term; it’s always horrible. But when it’s a whole new school it’s extra bad. And when your teacher’s a wierdo? No hope. I’d never been a clingy kid, but I stuck to Elemenope like chewing gum to a shoe. That first day I went everywhere with her.

---------------

Lunchtime was not so bad: jacket potatoes with cheese, pizza which was better than Mum’s home-made, and a slice of chocolate cake. I had seconds. Of everything.

The afternoon was endless. I tried to keep my head down and not stare at Mr Newton. He got us started on our Egypt project: I liked the sound of that. Dad had lots of books about history in his book-case. It’s a lovely book-case, with glass doors and row after row of beautiful books. I thought about working on the project with Dad, now that he was around all the time.

“Martha Gibbons!” Oh no. What did he want?

“Yes, Mr Newton?”

“What are we studying in this class, Martha Gibbons?”

“Err … Egypt, Mr Newton.” My voice was shaky, my head was wobbly; I’d been day-dreaming.

“Yes … Egypt. We’re talking about pharaohs. It’s not art, is it Martha Gibbons?”

“No, Mr Newton.”

“So why do I see a drawing in your work book? Is it a drawing of an Egyptian pharaoh?”

I looked at the page in front of me. It was not just a drawing; it was a whole comic-book series. There was my dad getting a book out of his book-case. There was me sitting beside him, reading to him. There was a big close-up of him smiling (something I couldn’t recall seeing in ages). The last one wasn’t finished; my pencil was still touching the shading I was doing to give the book depth. Guilty. Absolutely caught in the act.

I had nowhere to go, so I lied, “Actually it is … it’s a picture of me as a slave, reading a papyrus to Ramses the second.”

Mr Newton came closer and peered over my shoulder. “That looks like a book. The Egyptians didn’t make books, did they?”

He had me there, but I had to keep going. “No, Mr Newton, but they made papyrus … that’s a kind of paper. They used plants to make it and it really was just like paper, and they used to write on it. Their writing is called hieroglyphics; it was pictures and symbols. They didn’t really have an alphabet. And …”

“Take a breath, Martha Gibbons. Maybe you should be taking this class.”

My face was on fire. Every kid in the class was staring at me. But at least it felt like I wasn’t in trouble any more.

---------------

When the bell rang, I stood up to pack away my things. Elemenope had already piled up her books and was making for the lockers. I dropped my pencil case, and everything spilled on the floor. My hands were shovelling pencils, felt-tips and erasers into the open zipper of the unicorn case I’d been given for my birthday, when I saw the shoes. They were scuffed and completely overhung by folds of dark grey trousers. The cuffs wriggled. Was there a little puddle under one shoe? Gross. The machine voice came from above, “Martha Gibbons … when you’ve collected yourself, could we have a word?”

“Yes, Mr Newton.” My voice was strangled; I was bent double and it was getting hard to breathe down there.

I sat back on the chair to catch my breath. All the other kids were wandering out to be picked up, and Mr Newton stood beside me with his arms folded.

“Tell me, Martha Gibbons … did you study ancient Egypt at your last school?”

I shook my head, “No, Mr Newton.”

“Can I ask, how you learned what you told us in class?”

“I read about it.”

“On a computer, I suppose … something like Wikipedia?”

I’d never heard of that, so I shook my head. “No. In a book. Actually a few books. Dad has lots of books, but I borrowed a really detailed one from the library. It’s so interesting. Not just the pyramids, but what they believed in. Do you know, they used to shove tiny hooks up the dead person’s nose to pull out their brains? It must have taken ages – and they put the dead person’s organs in special jars; they’re called canopic jars. Then they wrapped them to make a mummy. It was amazing.”

“So … you read books … you go to a library. Interesting.”

I was waiting for more. None came. I sat there, waiting for Mr Newton to ask me another question, but he just stood there. I wanted to go, but I didn’t ask – at least not out loud.

Mr Newton said, “Yes, Martha Gibbons … you can go now.”

Comments

A fabulous piece of writing…

A fabulous piece of writing that does exactly what fiction aimed at adolescents should do: it's earthy, witty, graphic, absurd, dark and above all, highly entertaining. The setting is perfect and the characters and racy dialogue reminiscent of Roald Dahl. Highly recommended.

The writing is strong. I…

The writing is strong. I especially loved the clever use of the name “Elemenope.” It adds a fun, memorable touch to the piece! I would love to see how the story proceeds.

Great characters!

I love the characters, the story line, and all the descriptions. Was super fun to read.