As Dolly infiltrates the brutal world of a plumage factory, at home their servant is intent on destroying her employers' happiness and exposing the truth.

The new retiring room at Marshall and Snelgrove Department Store was causing quite a stir. Some ladies made special trips to inspect it, although they would not say so. Despite its modern comforts and advantages, it was not a place to linger, as no decent person would want to be seen there. The female digestive system ended at the stomach, after all. At least that used to be the case when the only public facilities were for gentlemen. Ladies were expected to stay close to home or venture out for only the briefest of periods.

It was mid-morning and hushed. Even women who knew each other only exchanged the odd word as they primped and powdered. In the cubicles others struggled with their skirts and clutched at their hats as they contorted themselves into positions that would avoid the sound of their tinkles hitting the water below.

At a quarter past ten, the entrance door swung open and banged against the wall. There were sounds of heavy breathing, puffing, an inelegant footfall. The occupants became alert. Had a male entered by mistake? Two ladies by the wash basins braved a glance and quickly averted their eyes. The interloper clattered into one of the empty cubicles.

The silence was palpable. The ladies were poised, listening. Nobody breathed.

Then a torrent of urine cascaded into the lavatory. The sound of a satisfied sigh added to the horror. None had ever witnessed such a blatant performance of a bodily function, although one of the more resourceful ladies took the opportunity to piddle with impunity, realising that any sound coming from her cubicle would be drowned out. The experience would leave most of them wary about visiting a public convenience ever again. What were they thinking to expose themselves to such indecorum?

There was a rush for the exit. Ladies emerged from their cubicles and hurried to wash their hands. They dared not glance at each other; to meet somebody’s eye would mean acknowledgment of the whole sordid affair, suggesting collusion. Best to just vacate the area as soon as possible.

The sound of urine dwindled to a drip.

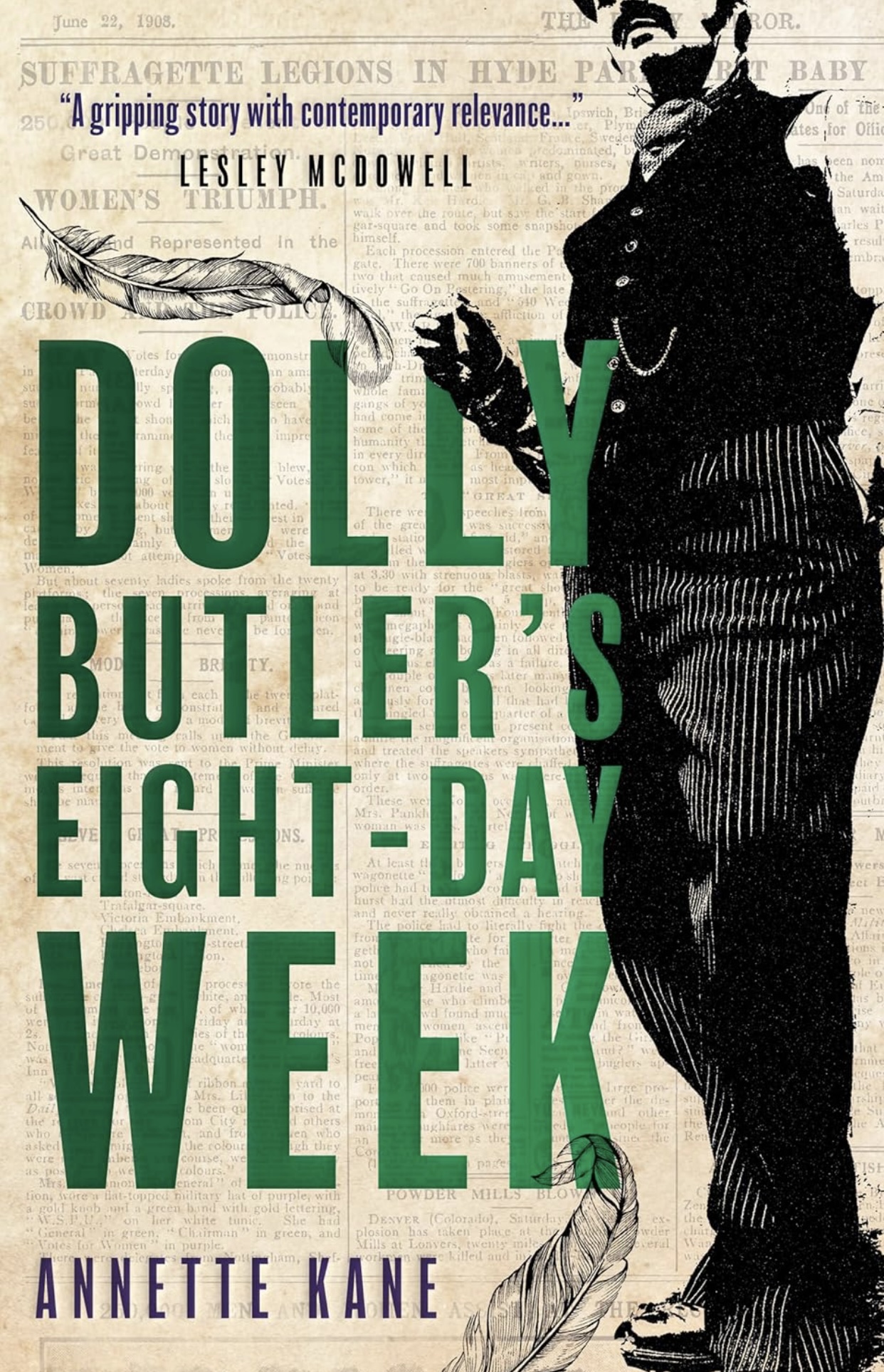

The exit door had closed behind the last of the ladies before the strange character emerged from her cubicle. She burst out like a small sleek monkey, her appearance being a match for her conduct: unfeminine, muscular and without regard for convention. The mannish clothes she wore were chosen for comfort, her scarlet tie for gaiety and to complement her dark complexion. True, she had a shabby look but it enhanced the impression of a Mediterranean wanderer who did not care if their skin tanned and their hair became brittle from the sun.

She was Dolly Butler, private detective, chaser of dreams, genius.

Fool.

DAY ONE FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 1908

SUFFRAGETTES ATTACK HOUSE OF COMMONS: MEMBERS HARANGUED FROM A LAUNCH

LONDON WEATHER FORECAST

Northerly to light variable breezes; fair today, becoming rainy late tonight or tomorrow. Remaining cool.

10.22 hrs. Dolly Butler

When I emerged from the cubicle, everyone had skedaddled for some reason. I filled the wash basin, plunged my hands in and pulled a face in the mirror, entertaining myself with an expression or two. Marvellous to have such pliable features. As I shook the water off, I said to my reflection, ‘Regarde la! Coquina, coquina!’

I tried out my cockney accent. ‘Barmy on the crumpet, ain’t she?’

‘Nah! She just ain’t yer pigeon, love,’ I replied to myself in a deep voice.

As I leant forward to inspect my nostrils, I noticed a trim little figure standing behind me, cute in her green twill coat and modish hat with its two perky feathers in a V-sign. Smirking, she was. Let her smirk. I didn’t care. I winked at her, surprised when she did not look away. Taking a cloth from the pile, I dried my hands and whistled a jolly tune. When I looked again the gawper had gone. Hadn’t made a sound. Impressive. I really must develop the skill of floating about noiselessly like that. Putting the cloth in the pail, I sneaked a couple more. Face looked a bit sweaty, so I pulled off my tie and shoved it in my pocket along with the cloths, and went on my way.

I paused to enjoy the hurry-scurry on the shop floor. What luck to find business rooms atop such a splendid place as Marshall and Snelgrove’s – and for five bob a week all in! The store was decked out in suffragette colours prior to this Sunday’s jamboree. I watched a couple of the less experienced shop girls as they fidgeted by their counters waiting to be approached, while other staff hovered at a customer’s elbow or demonstrated a glove. The shoppers seemed mesmerised as they glided about amongst the merchandise.

The sashes and branded scarves looked tempting at 2/11d. Caroline would like one, perhaps. Green for hope, white for purity and purple for loyalty. My hand ran over the satin charmeuse, soft and delicate. But why did my girl need a scarf if she never went out? It would just sit on the hall stand with the hat I had bought her and catch dust.

I already knew some of the floorwalkers and shop girls, and we exchanged greetings as I cut across the floor. Miss Belivet looked up with a coy smile as she sharpened her pencil. Her junior was plaiting lengths of mauve silk, heaven knows why. Mrs Tunks draped a cheviot mantle round a matron’s chubby bosom with a desperate enthusiasm. She looked like she tried too hard, and she had an unfortunate odour. I caught a whiff as I waltzed by.

The young miss who had watched me in the ladies’ was inspecting some green and purple feathers in a glass cabinet. She looked as pretty as a picture, with her rosy- red lips and platinum hair! However, the skin on her hand was red and inflamed. She didn’t look up but snatched it away as if she felt my eyes upon her. She’s not what she seemed to be, I thought as she walked off. Attention to detail was my stock in trade now. What an excellent idea it had been to try my hand at the detective lark! I was clearly a natural.

Beyond the brass doors that led to the back stairs, it was dingy. I zipped up to the floor below the shop girls’ attic dormitories, the tuneless trill coming from Professor Ambrose Cornboise’s Vocal Academy becoming louder. I hurried along the narrow corridor, past Madame Clarice’s Spiritualism and Psychometry Studio, to my offices at the

end.

Clammy air greeted me as I opened the door. Constant condensation on the windows meant we had to light a fire to cheer the place up, even in June. There was a strange mix of aromas – stale smoke, old socks and rubber. The previous occupant, Doctor Frankel, had dealt in prosthetics and left his stock behind when he’d done a moonlight flit. There were shelves of wooden and metal arms with their curling fingers and latex straps. The larger limbs jutted out from the wall at jaunty angles like a row of Moulin Rouge dancers, their leather harnesses dangling below like frocks. Glass eyes stared out in all directions from a cabinet and there was a selection of painted tin masks that had once provided a choice of face for any unfortunate with damaged features. The doctor had also left behind his faithful employee, Cyril Hare, who wheeled himself beneath the displays, a perpetual reminder of his limitations in the lower-limb department. I wasn’t sure we were going to get along. He was old-fashioned and fussy, with his pencils all lined up on his desk, and his boggle eyes watching from behind his pebble glasses, except while we conversed when he looked away. In his drawer he had a pile of Union Jack periodicals (the nationalist Empire rag), with stories of heroic captains, swarthy subalterns and uncooperative natives, which he pored over in his dinner hour. He had admitted to a preference for being an Assistant Investigator rather than Junior Prosthetic Limb Technician, as research and analysis fascinated him. I doubted his usefulness at undercover work, but if he knew his way around an archive he might earn his keep.

My other employee, Jessie Spink, had been recommended by my Australian friend Queenie Myers, who owned The Ham Yard, a café in Soho. She said the girl was “fair dinkum”, and desperate to be something other than a skivvy or sweated factory girl. At that moment, Jessie was standing on her desk fiddling with the light bulb that hung above it. Cyril had wheeled himself to a halt nearby and was eyeing her dainty feet in their cheap boots. He turned his head in my direction, eyes following shortly afterwards and stopping a few inches short of my face. ‘Good morning, Miss Butler.’

‘Morning! Jessie, what are you doing?’

‘Oh, hello there, Miss. I’m using my initiative, Miss.

‘Well, don’t. The caretaker can use his when he comes up to fix our lavatory.’ I had fiddled with the cistern myself but I was not tall enough to reach properly. I sniffed the air. ‘Hello, Blanche.’

Blanche’s greasy head jerked into view from one of the winged armchairs by the fireplace. She had removed her boots and rolled up her skirt. Her long skinny legs were so close to the fire that, feeble as the flames were, there was a whiff of singed wool from her dandruffy stockings. A clay pipe hung from her lips which she removed only to cough or to take a swig from her hip flask. She muttered a greeting.

We had known each other for years. She had recently become one of the shop’s store detectives and had tipped me off about the rooms after Doctor Frankel’s sudden departure. No doubt she had wanted me to take on the tenancy so that she would have somewhere to go during her frequent breaks rather than put up with the humdrum company in the staff rest room.

‘There’s a suspicious-looking lass hanging round the trimmings and assorted plumage, Blanche. Pale green coat,’ I said.

‘Hark at you!’ Blanche said, her head a-wobble. ‘Dolly Butler.’

I ignored her sarcasm. ‘She looked like a shoplifter to me. You might catch her if you get a wriggle on. I had a mind to apprehend her myself.’

That day’s paper was on Cyril’s desk and inside should be my advertisement for the Agency, officially making this our first proper day in business. My hands trembled with anticipation as I picked it up and scanned down the classifieds on the back page. ‘Has anyone looked for our advertisement?’

Jessie frowned as the light bulb flickered and died. She clambered down and peered over my shoulder. ‘There it is, below the one for bunion braces,’ she said, pointing to the boxed notice at the bottom of the page. ‘Dolly Butler, Lady Detective. Tel. HOL 367. Hold it still, Miss.’

‘I can see it, Jessie.’ I continued to read it out. ‘Have you something that needs investigating? If so, come to us. We welcome private enquires from interested parties about illegal activities, unlawful practices or mysteries. No crime too small or personal problem too big. That sounds good, doesn’t it? High- class firm with work undertaken by discreet and able detectives. Consultations free. Why not call in to our stylish new offices on the fifth floor of Marshall and Snelgrove, on the corner of Oxford Street and Vere Street, parish of Saint Thomas?’

‘Stylish!’ Blanche scoffed, and with another lashing of sarcasm, she added, ‘I thought if I spent my breaks up here you could teach me all about the detection lark.’

‘Nowt to do with my tin of best ribbon cut you’ve helped yourself to,’ I said. ‘It’s fine, Bolton. What’s a bit of tobacco between friends?’

Blanche tapped her pipe against the palm of her hand and threw the leftover ash onto the embers. ‘Let’s see that advert for bunion braces.’ She lifted her legs and beheld her misshapen feet. ‘A mature woman like me, on her feet all day.’ She slumped back again and her chest heaved.

I rolled my eyes. Blanche liked complaining. It was strange that someone like her should be employed by Marshall and Snelgrove, with its fine dining, library and fancy facilities. It even had a pet department with exotic birds and pedigree cats. She must be up to something, I thought, as I watched her rub her lumpy toes and replace her boots. Finally she rose to her feet like an unfolding yard rule. At least she looked less untidy at full height.

She belched, went to the door and said with a wink, ‘Bye for now, you ugly lot. Thanks for the shag, Butler.’

‘Any time, Blanche Bolton. And don’t forget that wench in the green coat. She’s up to no good, mark my words.’

After she had gone Jessie said, ‘Is she really a friend of yours, Miss?’

‘She was saying she’d had to pawn her false teeth earlier,’ Cyril said. ‘She only got them back this morning apparently.’

‘Take no notice of her.’ I turned to look at the photographs on the front page of the newspaper.

Jessie frowned. ‘I think there’s something dodgy about her.’

‘Oh, she’s dodgy all right.’

‘Will you excuse me, Miss?’ Jessie said after a few moments. ‘I need to spend a penny.’

‘Be quick,’ I said, although heaven knows, there was

little reason for haste. Jessie grabbed her hat, plonked it on top of her brown frizz and scurried out. I read my advertisement again, wondering why the girl needed her hat for a visit to the ladies’ room, but then again it was the Golden Age of the Hat.

Preparation for my new enterprise had not only included the study of English Law but also toxicology, ballistics, criminalistics, cryptography and psychology. I had sat through endless trials at the Royal Courts of Justice and the Old Bailey, and followed random people in the street on five occasions. Although challenged by my prey four times, I was now proficient at it. My new equipment included a magnifying glass, a Powell and Lealand microscope, a gimlet, a gemmy, binoculars, a torch kit, a Swiss Army Knife, and a gun licence (but no gun). I had acquired a hollow bangle that could hide a supply of narcotics, a cane with a secret compartment for maps and the like, and I had applied, using a male alias, to join a few London clubs that might be useful, including the Press Club, the Carlton and the Alpine Club (which I had done accidently thinking it was the Athenaeum). I’d lined up a handful of newsboys and taxi drivers as possible narks, and experimented with picking locks. Already a fluent speaker of Russian, Romani and Swahili, I had started to learn German, Polish and Greek. I had prepared properly this time. Success was assured.

Collecting a repertoire of disguises had been the best bit. I had rummaged through the chests at Willy Clarkson’s (Costumier and Wig Maker) for hours, hunting for suitable outfits and acoutrements. I became a regular round Hoxton and at Houndsditch Market looking for a second-hand frock coat, lounge suit, blazer and suchlike. My muscular body suited male attire gratifyingly well and, after Caroline’s initial giggles, we agreed I cut a dash. The shadow of hair on my top lip could be allowed to grow if necessary. As a female I could win the trust of women, but as a male I would be able to insinuate myself into masculine preserves. It had been a brainwave to set up the Bureau and be able to indulge my vagaries while earning a living at the same time. All I needed now was a client. Surely somebody had seen the advertisement? As I glared at the telephone, willing it to ring, Jessie reappeared, flustered and out of breath.

‘Bugger me, Jessie, what’s the matter?’

‘You’ll never guess what happened!’

‘In the Ladies’ Retiring Room?’ Cyril said, with annoying coyness.

‘I went to Mrs Bolton’s floor and...’ Jessie stopped. ‘And what?’

Putting her hand to her chest, the girl calmed her breathing. She plopped down onto her chair and flung off her hat.

‘Well?’ I said.

‘I nearly bought you a tie, Cyril.’

‘A tie? For me?’

‘Yes. For Sunday. I thought you might like a tie in the proper colours.’

‘I don’t know what to say.’

‘You don’t have to say anything because I didn’t.’

‘It’s the thought that counts.’

‘You can tie the thought around your neck on Sunday then.’

The girl was a nincompoop. I sent her to make a pot of tea. ‘You are going on Sunday, aren’t you, Jessie?’

Jessie popped her head round the screen that divide off the kitchen area. ‘Beg pardon?’

‘Sunday. You know, join a suffragette procession?’

‘I wasn’t planning to, Miss.’

‘You must, Jessie. Even Cyril’s going.’

‘Am I?’

‘I was planning to see my fellow.'

‘You have the rest of your life to see fellows. And besides, you can bring him along. Lots of men will be there.’

‘He’s dead against it, Miss. He says it’ll end with women wearing britches and men wearing frocks.’

‘That’s not what women’s suffrage means. Is the man an idiot?’

‘I don’t know, Miss. We haven’t been walking out long. All the girls are after him. He’s devilish handsome.’

‘Hear that, Cyril? Jessie’s got herself a heartthrob.’

Cyril glared at his fountain pen and went red. Jessie slunk back to the kettle.

I found my Capstan Navy Cut and tucked the newspaper under my arm. ‘I’ll be in my office.’

Jessie’s head popped out again. ‘Miss, we had a phone call earlier.’

‘What? Why didn’t you say?’

‘I took it, Miss,’ Cyril said. ‘Jessie was messing about with the eyeballs at the time.’ Cyril’s slender fingers opened his notebook. ‘It was Willy Clarkson. He said it was about his bill.’

Bloody hell, I thought. I must owe him a fortune. I closed my office door behind me, sat down and re-read my advertisement. I peered at the photographs on the front page of Flora Drummond on the Thames, but it was impossible to tell if any of my old set were on the boat too. Then I flicked through my copy of Ludgate Monthly, stopping at an article, ‘Why Are Suffragettes So Unattractive?’. They wouldn’t be suffragettes if they could get husbands, apparently. It robbed you of your looks and made you masculine too. I threw it down. Nothing I hadn’t heard before. Grabbing the telephone extension receiver, I dialled my home number. Caroline cheeped with delight at the sound of my voice and she assured me that she was missing me, that yes, she loved me more than words could say. No, she hadn’t been anywhere. I told her I couldn’t block the line for long, what with the advertisement being in the newspaper. The receiver pinged as I replaced it. It was worth checking. We couldn’t risk her being seen. I picked up the artificial hand that had been left there and worked the fingers with the leather straps. It flicked two fingers at me.