Chapter 1

Ask Me No Questions

Jack Owens shifted his weight uncomfortably from leg to leg as he stood behind a chair in the day room of Greenwood Acres Assisted Living. He decided then and there never again volunteer to chaperone second graders on a field trip. Jack caught the eye of his girlfriend, Jessica Reid—the teacher of this class and the person who volunteered him to assist. She gave him an understanding and sympathetic nod, for she could see how out of his element he was in this situation.

Jack was thirty-eight, right at six feet, and a little overweight. He’d never been married. No children. He ran his fingers nervously through his dark hair and let his eyes leave Jess for a moment to scan the room. Jess was divorced, childless herself, and three years Jack’s junior. She had a bubbly personality beneath that brunette hair and those bright blue eyes despite the horrible marriage she had endured for five years.

She also knew the children didn’t make him uncomfortable, but rather, the people living here—to whom the children were supposed to be giving holiday cheer. The field trip to the retirement home with this class of second graders came at the suggestion of the principal at Lake Drive Elementary, where Jessica taught. The principal’s daughter happened to be a nurse here. So it goes.

Jessica was happy to see the residents who gathered in the dayroom enjoy the presence of the children. While Greenwood Acres was not upscale and fancy like some facilities that catered to wealthy retirees, it wasn’t a dilapidated establishment, either.

Jessica smiled at Jack. He smiled back and gave her a raised eyebrow. The children’s interactions with the residents weren’t lost on him, either.

One of the residents in the dayroom, however, remained by the wall. He supported himself with a cane and looked out the window, paying little attention to the throng of children, Jack noticed. His yellow sweater with burgundy collars stood out against the wall’s light gray paint, and something about the old man piqued Jack’s interest.

Jack worked his way along the wall to find an opening among the children and the residents, slowly making his way toward the wall where the old man was standing. When he arrived, the old man glanced at him with a cursory nod of acknowledgment before returning his gaze to the overcast, dreary winter day through the window. Today was winter solstice, December 21, 2018. The weather outside was befitting for the first day of winter too.

Jack noticed that the old man seemed as uncomfortable as he was. And for some inexplicable reason, he was drawn to the old man. He noticed a small gift the man had received earlier from one of the children protruding from the bottom of his left hand, a figurine of some kind.

Inching his way toward that side of the room, Jack squeezed himself behind the occupied chairs facing the center. When he was two feet away, Jack extended his hand. “Hello sir, I’m Jack Owens.”

The old man turned slightly, looked down at Jack’s hand, then up into his face. He raised his right hand, still grasping his cane, and shook Jack’s outstretched hand with three fingers. Jack noticed the old Indian logo of the Washington Redskins—now the Washington Commanders—on the left front of the old man’s sweater.

“Hello back, young man,” came his reply.

The old man’s voice sounded weary, yet vibrant. His smile appeared the same way—tired and worn out—but not forced or fake.

“Pleasure to meet you Mr.—” Jack replied.

“Will Morgan, Mr. Owens. Likewise.” He nodded.

“Will, short for William?”

“No, short for Wilbur.”

“I see,” Jack replied, followed by the awkward silence that usually occurs when searching for the next words to say to a stranger.

Evidently believing their conversation was finished, Mr. Morgan returned to gazing out the window. Jack followed the old man’s gaze upward toward gray, low-lying clouds that threatened either rain or snow. He glanced over at Mr. Morgan’s face again and saw that he was looking directly at the hedgerow separating the facilities’ parking lot from the street beyond. His stare was unwavering, straight ahead; his eyes did not blink. What the old man saw outside the facility with his eyes was not what he saw in his mind, that much was clear. His hazel eyes seemed to see far beyond the front yard, the hedgerow. Something distant.

“Penny for your thoughts, sir,” Jack said, hoping the conversation was not over.

Without looking from the window, Mr. Morgan replied, “What is today’s date, son?”

Jack thought for a moment. “Friday, December twenty-first. Twenty-eighteen,” he added the year as an afterthought, just in case dementia was involved here.

“I see. Ask me no questions, son, and I’ll tell you no lies.”

“Pardon?”

Jack waited, but Mr. Morgan did not reply. After another moment, the old man brought the figurine still clutched in his left fist up to his chest and pressed it against his shirt. A single tear rolled down his cheek.

Jack looked down. “Are you OK, Mr. Morgan?” Without taking his eyes from the window, Mr. Morgan replied, “No son, not really. But it is what it is.” He paused for a second. “And it was what it was.”

Jack didn’t know what to say, so he continued silently observing Mr. Morgan at the window, how he clutched the figurine against his chest and white-knuckled his cane. The prominent age spots on his hands.

He stayed by Mr. Morgan’s side, unsure if he might fall. Whatever he was thinking about appeared to have a powerful hold on his mind.

Jack stood with Mr. Morgan for five or ten more minutes with one arm at the ready in the event the old man fell. The sounds around the room faded into the background until they both heard Jessica call out. It took a moment for Jack to locate her, standing in the middle of the room.

“Help me get my class together, it’s time to go.”

Jack nodded at her as Mr. Morgan looked his way again. “I’m sorry Mr. Owens, I was thinking about something that happened a long time ago.” He wiped his face with his sleeve.

Jack could clearly see the feet of the figurine protruding from the bottom of his hand now. It appeared to be brown boots painted olive drab.

“Are you sure you’re OK?” Jack asked. “I’m right here.”

“Yes, I’m fine. Thank you, son, for your concern.”

“No problem. You seemed very upset a moment ago.”

“Well, its December twenty-first, that’s all.”

Jack wanted to know more, and now he had no time. “A memory?”

“Yes, and not a good one.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be son, very few of you young people care enough to even speak to us old farts.” Mr. Morgan sighed. “Sorry, I’m not too talkative today.”

Jack smiled. “Another time, maybe?”

When Mr. Morgan didn’t reply, Jack turned away to help Jessica.

“Would you really like to know what I was thinking about? Really?”

Jack glanced back at Mr. Morgan, still framed by the window.

“Yes,” Jack called. He’d seldom seen such raw emotion and was curious about what had happened to the old man.

“If you’d care to visit me some time, I might be able to tell you. And a few other things as well.” With that, he turned and quietly left the dayroom.

“OK, I’ll do that,” Jack called after him. He slid between the chairs and started toward Jessica.

After Jack rounded up all the children with Jessica and two other chaperones, they did a head count.

Jack saw Mr. Morgan again as they herded the class outside to the activity bus. He was making his way down the corridor at a slow, steady pace, his cane tapping on the floor.

Once all the children were seated, Jessica joined Jack in the back.

“Thanks for your help today. Just the presence of a man seems to keep those kids in line,” she said.

“Not a problem.”

“Really?”

“Really. You’re welcome,” Jack replied with a smile.

“Who was the man at the window? He seemed to have your full attention there at the end of the visit.”

“Just some old man, staring out into space. I thought for a moment he was not all there, but after speaking to him, he seemed fairly alert, you know?”

“What did you talk about?”

“Nothing, really. He introduced himself. He asked me the date. Then he went back to staring out the window.”

“It looked like you two really hit it off over there.”

Jack shrugged. “Who knows. I think something was bothering him. He teared up a little.”

“Mm—yes. He seemed to be fairly aware of things, right?”

“Yeah. When I asked him if everything was OK, he just told me to ask him no questions, and he’d tell me no lies. I thought that sounded like someone who knows where he’s at and the situation he’s in.”

“Well, it’s a pretty nice place as far as retirement homes go. What kind of situation do you think?” Jessica asked.

“He’s very old, and he can’t have too much time left. He’s stuck in an assisted living facility and seems to be one of very few people in there who can still walk on his own. Man, that’s depressing. To me, at least.”

“I have to agree. I can’t—don’t want to imagine what it must be like. I suppose some of the people living there have no family that visit. And yes, many of them are wheelchair bound. It is depressing.”

“He invited me to come visit him.”

“Well, you ought to. The holidays are here, you’ve got a week off, and I’m going to be gone for several days.”

Jack stuck out his lip. “I know.”

Jess smiled empathetically. “I’ll be back before you know it.”

They fell silent. Jack was not thrilled that Jess was leaving him behind to visit family in Oklahoma, but he understood. They’d only been dating for a short period of time. He was fairly used to being alone over the holidays, anyhow.

“I can give you the contact information for the nursing coordinator I worked with to schedule this field trip. She’s a nice lady, Bea Nelson.”

Jack had never really known his father, who’d left his mother two years after Jack’s birth. His parents had never married. Ostracized by her own family due to having a child out of wedlock, his mother had struggled to raise Jack alone through the ’80s, working many double shifts as a waitress and a housecleaner.

He had little recollection of his maternal grandparents and none of his paternal ones. He only counted an aunt (his mother’s older sister) and her son as extended family and had not seen them in years. His mother had passed away in 1999, almost twenty years ago. That was also the last time he saw his father, when he stopped by to pay his respects at her wake. The man simply disappeared again, and Jack really didn’t care. His father had barely acknowledged him at the funeral home.

A miracle Jack survived at all, much less as a successful accountant and financial advisor. He managed, with his mother’s constant encouragement, to avoid most of the pitfalls of youth: drugs, alcohol, gangs, and the like. He kept good grades in school and was talented enough to be a starting point guard on the varsity basketball team throughout high school.

College wasn’t possible, as his mother could barely keep them in an apartment while working two jobs. Jack joined the Navy and planned on using the military college fund to go to school. He’d been in service a year, stationed at the Navy Yard in Norfolk, when his mom passed away from a stroke at thirty-eight, the same age he was now. The Christmas season of 1999 was spent in his hometown of Roanoke, Virginia burying his mother, and had since become a depressing time of the year for him. With Jessica leaving for over a week, this year promised the same.

He'd served his four years in the Navy, and in 2002, he started school at a small college in Virginia, obtaining a degree in business. He worked as a bookkeeper and steadily added more certificates, licenses, and schooling before he began his accounting business in Greensboro, North Carolina at age thirty. He’d since added financial advisement to his credentials. Jack was not rich, but he wasn’t struggling, either.

The activity bus pulled into the school’s parking lot thirty minutes later. The schools in Greensboro had all let out at noon that day, the Friday before Christmas. The children were hyper and beyond enthusiastic to join their parents and head home for Santa, Jack noted. But the nearly vacant parking lot only reminded him he was about to be alone again.

Jack sighed, both glad and disappointed that the excursion was over. He pulled Jessica close, his arms around her waist. “I’m going to miss you,” he said, and gave her a kiss on the cheek.

“I’ll miss you too.”

“What time does your flight leave again?” he asked.

“I’ll need to be at the airport by five a.m. Are you still up for taking me?”

“I guess so,” he replied.

“I’ll be back before you know it,” she said.

“Promise?”

“Pinky swear.”

“Well Miss Reid, would you care to go to dinner with me tonight?” he asked.

“Why certainly, Mr. Owens. Where?”

“As much as I may regret it, it’s your choice this evening.”

“Regret it? Why?” she asked.

He smiled. “Well, every time we go out to dinner, and sometimes even lunch, and you are the one who is choosing the restaurant, the choice seems to be difficult to make, and it changes about six times.” He winked at her.

“Oh, that’s not true.” She smiled and gave him a light slap on the back.

“Oh, it’s true, and you know it is,” he laughed and pulled her into an embrace. He looked into her eyes and suddenly kissed her.

After they kissed, she blushed slightly and said, “Mr. Owens, not here at school.” But her eyes twinkled while she said it.

He smiled back and let go of her, widening his arms with a mocking gesture. “Miss Reid, no children are here. They’ve all gone home.”

She laughed and pointed toward a nearby wing of the school building.

“They do have security cameras, you know.”

Jack glanced toward the school, feigning worry. “You mean, they’re functional?”

“Don’t you start.”

“Party pooper,” he said, and took her hand, beginning the short walk to their cars.

The shadows had already grown long, as it was winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. They reached their cars and agreed on the time Jack would pick her up for dinner. She’d still not yet decided where to eat, but promised Jack she’d know by the time he picked her up.

Chapter 2

Will Morgan

Will Morgan arrived at his small apartment in the Greenwood Acres shortly after the departure of the class of second graders. He placed his walking cane on the hook on the wall and settled into his old leather easy chair. The chair was the only item of furniture he still had from his life away from the facility.

He had moved here four years ago, shortly after his wife of sixty-plus years, the woman he still referred to as his lovely Katelynn, passed away.

When she died, he was eighty-nine, and knew then that he could not, and had no desire to, continue living in their home. After sixty-three years of marriage to the love of his life, the walls seemed to close in on him without her there.

He looked around at the small apartment and his mind began to drift back in time, to his youth—and his maturation on the battlefields in Belgium in World War II.

Will was born in 1925, the fifth of six children, the youngest of four boys. He grew up on a farm in north central North Carolina. His mother was a homemaker and kept everything running in the house, including his siblings. His father operated the farm and worked as a carpenter and plumber before transitioning into heating and air-conditioning repair.

The family weathered the Great Depression years as well, never coming close to losing the farm, though those years were tough.

His father was a World War I veteran but said little to his children about the experience.

Will was his father’s nickname for him. His brothers called him “Bur,” and his mother and sisters called him Wilbur. His family was close-knit when he was young.

His oldest brother, Mathew, was born in 1917. Next, his sister, Mary, was born when their father was in France in 1918. Marvin and Calvin were born in 1921 and 1923 respectively, then Wilbur in April of 1925, and finally his sister, Alice, in 1927.

Growing up during the Depression were uneventful years, except for his brother Mathew. He graduated from high school in 1935 and had a promising career as a baseball player shortened by an accident when a large tree limb dropped onto his right foot after a winch broke. Mathew and his father were trying to move the limb out of their driveway after a storm. The doctors tried to reset and save his foot but had to amputate after a week. Mathew then decided to study accounting and made that his career.

Mary wedded in 1939 and moved away to Charlotte, North Carolina about two weeks after Marvin graduated from high school. Marvin joined the Navy in September of 1939, three days after Germany invaded Poland.

Calvin graduated from high school in May of 1941 and spent the summer trying to decide what he wanted to do. War clouds were on the horizon, and those weighed upon his mind.

December 7 and the attack on Pearl Harbor made his mind up for him. On December 15, he joined the Marines.

Will himself had been aloof toward the growing war prospects before the Pearl Harbor attack. His brother, Marvin, was assigned to Pearl Harbor and aboard the heavy cruiser USS Chicago. He was in a task force with the aircraft carrier Lexington that left Pearl Harbor on December 5, thus missing the Japanese attack.

That, along with Calvin’s enlistment in the Marines caused Will to pay attention to what was going on in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

He decided if the war was not over by the time he graduated from high school, he would enlist rather than be drafted.

Marvin served on the USS Chicago through the battle of the Coral Sea, some months after the Pearl Harbor attack. He was wounded when the ship was sunk by Japanese air attacks at the battle of Rennell Island in January of 1943. The family received word of his WIA in March, and after his hospital stay in the Pacific, he returned home to convalesce. Marvin was present when Will graduated from high school and returned to the Navy three days later, the same day that Will enlisted in the Army. He was reassigned to the battleship USS Nevada and met the ship in Norfolk, Virginia where it was being refitted.

Will left home in late June of 1943. He was sent to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for basic training. Even now he smiled to himself as he recalled his appearance in 1943, a strapping six- foot, lean boy with a full head of dark brown hair. Ready to become a soldier.

After training, he was assigned to the 424th Infantry Regiment in the 106th Infantry Division. His regiment was sent to Tennessee in early 1944, then to Camp Atterbury in Indiana in early spring. There he met and befriended Al Baker from West Virginia. Al had gone through basic training at Camp Atterbury and was assigned to the same regiment. He became an instant friend, a guy who shared the same values and upbringing, the same general outlook on life.

Their regiment went to Massachusetts in mid-October and departed from New York to England on the October 21, arriving a week later. His division arrived in France on the December 5, and five days later crossed into Belgium where they were stationed at Winterspelt.

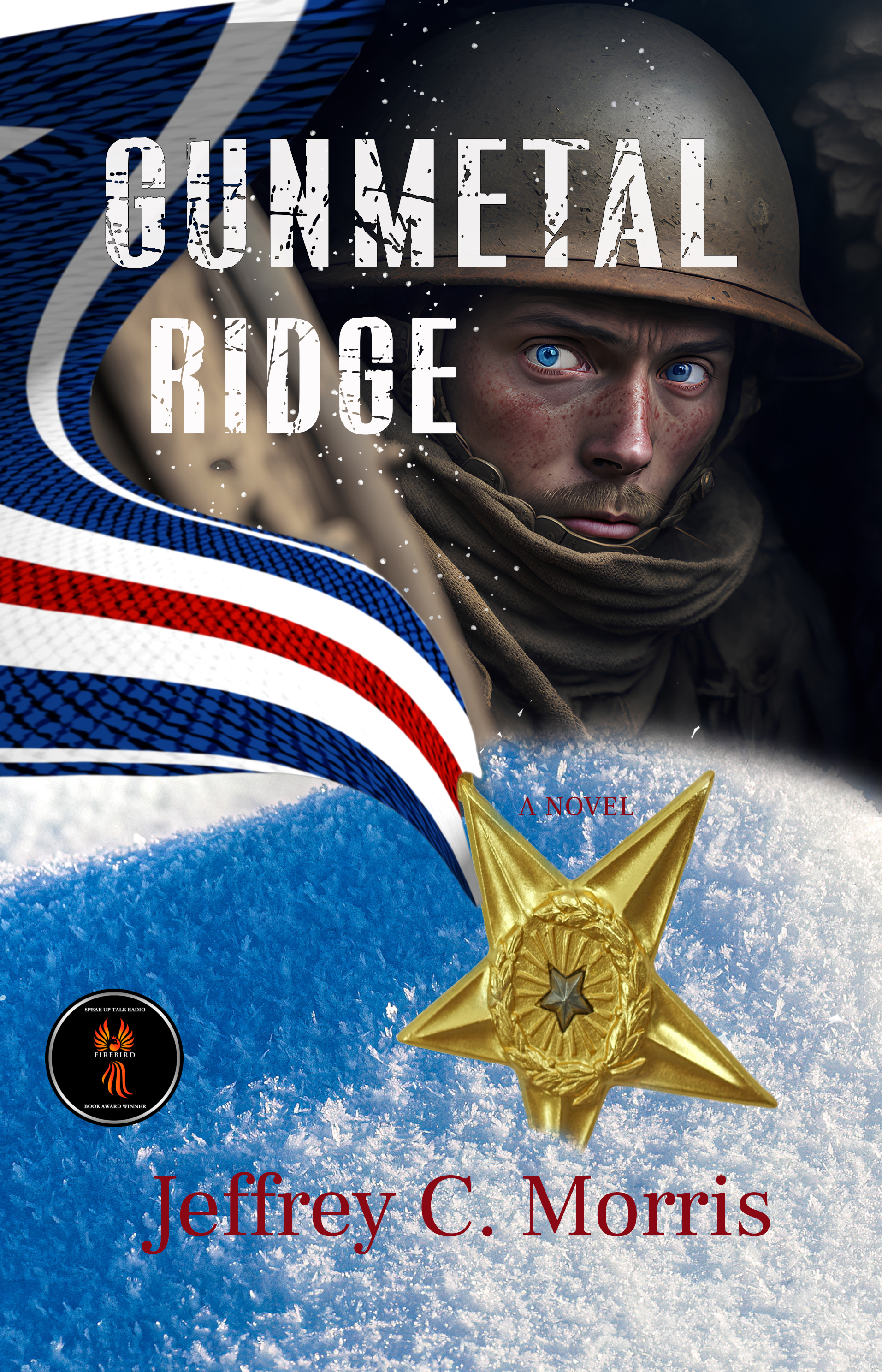

On December 16 the inexperienced and untested 424th Regiment was at the forefront of the initial attacks across Belgium, historically called the Battle of the Bulge, the final German offensive on the western front in Europe. This was also the first day of five wrought with confusion, danger, and a baptism of fire that erased any remaining innocence he may have possessed and left him with memories that haunted him to this day.

Will came out of his thoughts with a start. He noticed his hands were shaking and a bead of sweat had formed along his upper body. A tear rolled down his cheek as he thought to himself, “Seventy-four years ago. Why does it still seem like yesterday?”

He shook his head to try to clear out thoughts of 1944 and replace them with memories of other holiday seasons and happier times. Most were pleasant memories of past gatherings with his bride and daughter, his siblings and parents, days when they were all still alive and healthy. Those brought a smile to his face.

The figurine that one of the children had gifted him, Will realized, he still held down in his lap. Will put on his glasses, turned on his reading lamp, and adjusted the light to get a better look at it.

The hand-painted figurine was about six inches tall and the uniform, the World War II era Army Dress. Will looked at the painted figurine and admired the detail. The colors were accurate for the time. Accurate enough to be a six-inch version of himself from 1944, he mused, except this was a captain, an officer. He was just a private first class on this day in 1944.

He glanced up at the 11 x 14 picture of him taken with his family taken in 1961, and noticed not just the picture, but his own reflection in the frame’s glass. He sighed. He still had a full head of hair, brown replaced with silver, and the six-foot frame could now barely stretch up to five-ten. Broad shoulders were replaced with a stooped hunch. His eyes drifted away from his reflection to the light blue wall around the picture, then back to the figurine in his hand.

He wondered why a small child he did not know would gift him a high quality, hand-painted figurine—and could find no logic as to why he was chosen to receive this gift, especially on this day. Perhaps the gift was just a coincidence because surely no one from the school could have known that on this day in 1944, he was amid the last German offensive on the western front.

Will’s mind drifted back to that winter in Belgium so long ago. He could still see the slope of the hill leading down to the road that led northeast toward St. Vith and his squads' final position on a ridge near the village of Burg-Reuland before being forced out of the line by advancing Germans. He saw the destroyed German and American vehicles beside the roads and in the fields, and numerous discarded weapons of the wounded and dead. He could hear the cries of the wounded, the shouts of fellow soldiers, the shouts in German from the advancing enemy, the sharp reports of rifles firing, the ping of his own M-1 rifle upon ejecting the clip after his eighth shot fired. The sounds of tree branches breaking from shelling and the impact of bits of dirt, rock and wood hitting him in the helmet. He thought of the awful kick to his shoulder from the twelve-gauge Browning Trench gun, a shotgun he’d acquired as a secondary weapon, and the resulting ear-splitting blast from the weapon.

December on the western front chilled to the bone, accompanied by dirty snow and mud, lots of mud—mud as far as he could see. Somewhere in that mud were Germans—in front, possibly behind him, as gray skies dumped even more snow.

The smells—the smells too, he could not get out of his head. The acrid mix of gunpowder, blood, dirt, and grime. And especially, the smell of death. He noticed then how his hands shook; oh, how he needed to dial it back.

Will let the memories slowly fade away and brought his thoughts back to the present. He needed to move around. When he finally stood up, he’d have to stay stationary for a moment to ward off the dizziness. After finding his bearings, he retrieved his secondary cane from the little stand beside his chair. He walked over to the TV stand and placed the figurine next to the large television, on the right.