CHAPTER 1

The Promise

“Phil is well-known for keeping his promise to serve God, a promise that I believe most grunts make during combat. I know that I did.

Phil’s story is a great one!”

David “Chucky” McKee 1st Platoon

The weather in Vietnam in late February can fluctuate from the mid-fifties to as high as the mid-nineties. On the morning of February 28, 1970, PFC Philip Salois was getting ready to board a helicopter from his Fire Support Base (MACE) lo- cated about fifteen miles east of Xuan Loc, a city northeast of Saigon. He, along with members of two platoons (approximately 54 soldiers) from the 199th Light Infantry Brigade were headed to an area just south of a small village called Suoi Kiet, where the 133rd North Vietnamese Army Battalion might be located. The mission of the two platoons was to find

and destroy the battalion.

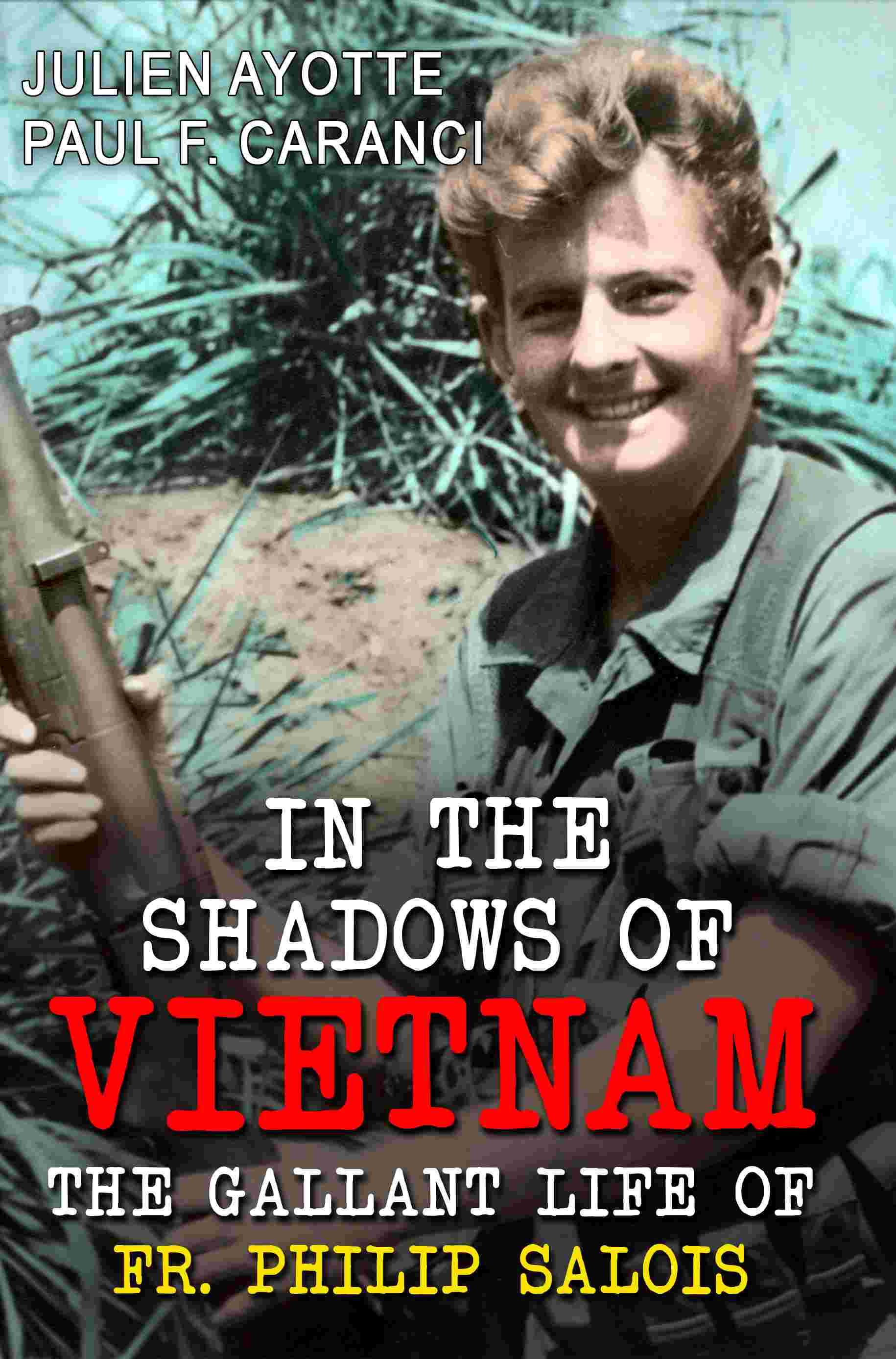

Twenty-one-year-old Philip Salois enjoying a quiet moment in Vietnam. (Circa 1970 photo courtesy of Fr. Phil Salois)

Phil had been drafted into the service in March 1969, just months

after having lost his deferment when he dropped out of college at Cal State Fullerton. In September 1969, a mere six months after being draft-

ed for military service, he was deployed to Vietnam. In his first months there, he saw his fair share of combat, trudging along the dikes of rice paddies, looking for an elusive enemy who chose when and where to en- counter their American adversaries. So, Phil’s initiation into combat had

2

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

thus far been minimal, other than an occasional comrade being killed or losing a limb while tripping on a landmine.

While the fighting in the rice paddies was wide-open, the Suoi Kiet area was considered jungle warfare, not at all a soldier’s friend. And in late February and early March, temperatures were rising and the two pla- toons could expect heavy humidity, scorching heat, and a bug-infested jungle growth. As the soldiers boarded the two helicopters that would take them to their destination, the silence among the men was deafen- ing. Vietnam was not a place where you made a lot of friends, because you never knew from one day to the next if that ‘friend’ would still be alive. Although Salois knew a few people in his platoon, he, like so many others, opted to maintain relative silence on the twenty-minute flight to their target.

The helicopters reached their destination without incurring artil-

lery flak from the North Vietnamese ground forces along the way. They

unloaded the platoons1

in a clearing at the edge of the jungle area.

Although Salois’ brigade normally consisted of three platoons, the third

platoon had been left at MACE for this excursion. Salois was in the first platoon to lead out when they landed. His squad covered the rear, while the other three squads blazed a trail slowly through the jungle, the sec- ond platoon following closely behind.

Late that afternoon, around five o’clock, the lead platoon found what appeared to be an elaborate enemy bunker complex. Nightfall wasn’t far ahead at this time of year, so the captain of the unit decided they would not mount a siege at this late hour of the day. Instead, the platoons retraced their steps, retreating to a clearing where they could camp for the night.

The Captain, Osvaldo Izquierdo, was inexperienced in jungle war-

1 The American military structure in Vietnam consisted of the following:

Squad = the smallest unit of men generally consisting of about seven people.

Platoon = the next smallest unit generally containing four squads or between 27-30 people.

Company = consisting of four to five platoons or between one hundred and eight to one hundred fifty people.

(The companies in the 199th included Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, and Delta Companies) The E platoon doesn’t generally go out. They carry mortars and are usually stationary.

Battalion = consisting of three to four companies.

Brigade = consisting of about four battalions.

Division = contained all the above. (NOTE: The 199th Light Infantry Brigade was its own higher authority. It had its own general and there was no division over it.)

IN THE SHADOWS OF VIETNAM

3

fare and was not an infantry captain, having spent his military time in logistics. He had decided, however, that to qualify himself for further promotion, he needed combat experience. Because the previous captain of the 199th had exhausted his field time, Izquierdo seized the opportu- nity to become the platoons’ needed replacement.

That night, the platoons were very tense. While they knew where the enemy was located, they also assumed the North Vietnamese knew where the American patrols were as well. Normally the men would share guard duty, alternating shifts every hour or so. On this night, however, nobody slept, fearing that the enemy might attack under the cover of darkness. All the men were on high alert. They knew all-too-well that the following morning, March 1, would clearly entail confrontational com- bat with the enemy.

In the early hours of the next morning, Captain Izquierdo ordered the two platoons to march down the same trail they had cut out the day before instead of taking the additional time needed to blaze a new trail with their machetes. Consequently, the enemy was waiting in a U-shaped ambush as the 199th approached.

The enemy bunkers opened fire on the exposed platoon, quickly scattering Salois and the others to the ground. The front element of the platoon was cut off from the rest of the group and, as the remaining men formed a defensive line to return fire, they lost contact with the group out front. Every platoon has its own radio, but the radio in Salois’ pla- toon was destroyed by enemy fire, leaving his unit no way to contact the front unit to determine their status.

It was determined on short order that six men were separated from the rest, hunkered down in a clump of trees ahead of the others who had established a defensive line and dug in. The inexperienced captain had unwittingly marched the platoon right into the ambush with the enemy surrounding them on three sides. American soldiers were care- ful to shoot high for fear of hitting their own men with the gunfire. The trapped men were isolated for at least twenty minutes, and no one seemed to know what to do. Captain Izquierdo ordered his men to re- treat to relative safety behind the defensive line until more help arrived. Salois, however, thought to himself, If I were trapped out there, I would want someone to come and rescue me.2

No one moved, no one spoke.

2 Authors interview with Phil Salois on April 24, 2023.

4

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

“I’m going out there,” Salois yelled. “Somebody’s got to let these

guys know we’re looking out for them.”3

Another soldier, Herb Klug, whom Salois knew, though the two

were not close friends, volunteered to go along with him. “If you’re go- ing to do this crazy thing, I’ll go out with you. But let’s have a little plan. You see that boulder out there? Let’s make a run out to that boulder and use it for cover.”4

Others shouted back at Salois, “You’re crazy, all you’ve got is that (M-79) grenade launcher, and Klug’s only got an (M-16) rifle. You’ll nev- er make it.”5

Salois and Klug didn’t know who was trapped out there, but they were soldiers who needed help to get back, assuming any of them were even still alive. Before heading out with Klug, PFC Phil Salois took a mo- ment to pray, making a promise to God.

“I’m going out there to get these guys, Lord, and if you get me out of this place safe and sound, without a scratch, I’ll do anything you want.”6 Moments later, both took off for the large boulder, bullets whistling

by them as they low-crawled the entire one hundred fifty feet to the rel- ative security of the large rock. As they took shelter behind it, panting and sweating profusely, they began spraying their right flank with small arms fire while Salois lobbed grenades from his M-79 Grenade Launcher as fast as he could load it. All of this was to divert attention to Klug and him, and away from the six pinned down soldiers. Enemy bullets began bouncing off the boulder as the two men crouched behind it. Their ef- forts provided enough of a diversion for four of the trapped men to make a run back toward the relative safety of their line. Others in the platoon also began firing at the enemy’s defense positions to add to Salois’ and Klug’s diversion.

One of the four to make it back to safety was, ironically, Salois’ only close friend in the platoon, PFC Nick Aragon from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Despite their valiant effort to return all the trapped men, there were still two unaccounted for. They were LT Terrance Lee Bowell and PFC Michael Kamrat, affectionately nicknamed “The Rat.”

“Either they’re too wounded to move, or they’re dead,” Salois rea-

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

IN THE SHADOWS OF VIETNAM

5

soned. “Let’s make a run back for our line right now while we can,”7 Klug shouted. Salois agreed and they began crawling in the brush side by side, heading directly back to their defensive line. They received supportive fire from the platoon members who were shooting over their heads as the two focused on the distance to safety ahead of them. Salois reached their line first, looked beside him, then behind him, and asked,

“Where’s Herb?”

One soldier shouted, “He didn’t come back.”8

Salois looked back in the field and saw Klug laying on his stomach, face down, and not moving. For a second time, he crawled into harm’s way back to the spot where his companion lay and threw himself beside Klug. Salois tried to drag Klug to safety, but couldn’t budge him. It was the first time Salois experienced the meaning of the term ‘dead weight’. Another soldier arrived, and together, they dragged Klug back to safety. Once there, they removed his helmet, only to find that Klug had been hit with a fatal bullet that most likely deflected off a rock and penetrated his chin and travelled up through his head. He died instantly.

Salois was now running on pure adrenaline, prompting him to risk making a third trip toward the tree line where two men were still trapped. Two other men accompanied him this time. When they reached the grove of trees, they found that LT Bowell was dead and that PFC Kamrat was bleeding profusely as he covered one of his eyes with his hand. Though badly injured, he was able to make it back to safe ground with assistance as one of the men carried the Lieutenant’s body back as well.

Within minutes, Medevac helicopters arrived to quickly remove the dead and wounded. Salois was in shock. His platoon had been decimat- ed. Of the twenty-seven men who started out that morning, only seven remained unharmed. Eighteen had been wounded, and two were dead. The other platoon and the seven remaining soldiers from Salois’ platoon left the area to seek shelter in a more secure place away from the action. Friendly artillery firepower soon arrived in the jungle area the 199th had just vacated, but all Salois could think about was, “Oh, my God, they’re going to come and finish us off.”9

One would have thought that the remaining platoon had seen

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

6

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

enough fighting for a while, but the very next morning, headquarters delivered another twenty troops. There were still ten days remaining in the mission, which had not yet been accomplished. A new Lieutenant, by the name of James Edwards, an African American, had been sent in to re- place LT Bowell. The other nineteen soldiers sent to join the 199th were inexperienced in combat, but Lt. Edwards was very qualified to handle the task of training them.

The inexperienced Captain Izquierdo was removed from the field, where he never should have been anyway. For the longest time afterward, many of the soldiers who survived this ambush hated the Captain for his poor judgment that day. Had the platoons blazed a new trail that morn- ing, it is possible that they may have evaded the ensuing ambush. That “what if” question is one that Salois and the other men of the 199th would never be able to answer.

For their courageous action that day, Phil Salois was to be awarded the Silver Star, while Herb Klug, who died in the rescue attempt, was to be honored posthumously with the Distinguished Service Cross.

“I don’t remember much of what happened after that,” Phil Salois said. “I must have numbed out. I have very little recall. But I don’t think I ever felt as close to another human being as I did with my buddies here in Vietnam. I’ve learned to rely on others for my life. And I’ve formed a bond that’s closer than blood brothers.”10

Life, however, had many more surprises in store for the twenty-one

-year-old.

10 Ibid.

CHAPTER 2

1944

“I love you too, Walter, but if you want to marry me, you’re going to have to come and get me,”

Hélène Henriette Podevin

In June 1944, Paris had recently avoided being bombed. A Swedish neutral had convinced General von Cholitz of the German army that bombing Paris would serve no purpose. The Allied army was fast approaching and the Germans would soon be forced to surrender the city to the French.

In August of that year, skirmishes broke out between the resistance fighters and German troops throughout the city. Cholitz, under orders by Hitler, was to detonate explosives carefully placed under all the monuments of Paris. Realizing the centuries of culture present in these monuments, Cholitz sent a message to the Allied Army urging them to move quickly on Paris before other German officers took action for which he could not be held responsible. General Charles DeGaulle proceeded toward Paris along with General Jacques-Philippe LeClerc, Commander of the Second French Armored Division. French troops, not Americans, were the first to enter the capital.

On August 25, as the French troops began entering Paris, more fighting broke out with the Germans resulting in serious damage to the Hotel Continental, a short distance away from the Hotel-de-Ville on Rue de Rivoli (city hall). Shortly thereafter, the Germans initiated a cease fire. A surrender had been signed and General DeGaulle was presented to the French people in a victory celebration that evening at the Hotel-de-Ville.

Walter Ernest Joseph Salois was a twenty-eight-year-old American

8

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

soldier assigned in Paris in early 1944. He had been assigned to the 336th Ordnance Battalion, an ordinance company, but was used primarily as a French interpreter by the military because of his fluency in French. He was standing outside city hall as General DeGaulle spoke that night, when a young French girl caught his eye. She was beautiful in his mind and, when she glanced his way, she smiled and blushed slightly. The young girl was but sixteen-years-old.

Prior to World War II, Walter had entered the religious order of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart in Woonsocket, Rhode Island and had for a time been teaching at Mount Saint Charles Academy there. Although he served the order for eight years, he had not yet taken his final vows. When he attended a baseball game with some other brothers, Walter was caught smoking a cigarette by another brother, a clear and serious viola- tion of the brotherhood. As a result, he was terminated immediately by the order. Distraught, and possibly also relieved at the incident, Walter joined the Army. Following basic training, he was shipped to Paris.

Hélène Henriette Podevin, the young sixteen-year-old who caught Walter’s eye, had lived in Paris with her parents her entire life. The thought of living a life of freedom without the German occupancy was clearly a relief to many. Having only a fourth-grade education when Hélène was forced by her parents to go to work to aid in supporting the family, she had worked in an electric factory for nearly eight years. Her

mother, Henriette Hélène Podevin, and her father, Gaston Leopold Quainon, had never legally married, and in the eyes of the Catholic church, Hélène could not take her father’s last name.

Gaston Quainon was an alcoholic and unemployed during most of the war years, one of the reasons Hélène was taken out of school to go to work. Her mother was a housekeeper, and the wages she earned were clearly in- sufficient to raise Hélène and her two half-brothers, Raymond and Maurice

Quainon.

A beautiful young girl, Hélène Henriette

Smitten by this young beauty, Walter was determined to meet her. The second time he saw her while he

Podevin, knew from the moment she met him, that Walter Salois was the man she would marry. (1945 photo courtesy of Fr. Phil Salois)

IN THE SHADOWS OF VIETNAM

was walking the streets of Paris with other American soldiers, he approached her and asked if she would join him for coffee at the Café Royale on Rue de Vanves. She cautiously accepted and, at first, their meetings were always during the day and in a public place. As time went on, however, the attrac- tion between the two became ap- parent, so much so, that one of Hélène’s bosses, Madame Assola, from the electric company where she worked, saw the two holding

9

hands one day while strolling along the Champs Élysées.

Madame Assola, along with her mother, Madame Beauduret,

casually mentioned to Hélène’s

Though twelve years her senior, Walter Salois began dating Hélène Podevin, against her mother’s wishes, in 1944, when she was just sixteen. The couple is seen here in 1945 in Langres, Haute-Marne, France (Photo courtesy of Fr. Phil Salois)

mother that they had seen her with an American soldier, much to her mother’s dismay. When Hélène returned home for dinner that after-

noon, her mother confronted her.

“Hélène, Madame Assola et Madame Beauduret told me that they saw you this afternoon with an American soldier. Is that true?”

“Oui, Maman, I met him several weeks ago. His name is Walter Salois, and he speaks very good French.”

“Oh, mon enfant, don’t get involved with Americans. They will love you while they are here, but when it is time to leave you and go back to America, they will never have anything further to do with you. I have seen it happen too often. They just want to use you.”

“Walter is not like that, Maman. He is different, I can tell.”11 Henriette could clearly see that her daughter was more than merely attracted to this American soldier. She knew that she had to stop this relationship as soon as possible before her daughter’s heart was broken when he returned home to the States.

“American soldiers are all the same. He will love you, then leave

you. Your father and I forbid you to see him again. And if you disobey us,

11 Ibid.

10

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

we will send you to Grand’Mère Laure’s in Langres, far away from Paris and this soldier.”

“I like Walter, Maman, and I will continue to see him as often as I can,”12 Hélène protested.

Within a week, true to her word, Henriette made arrangements for Hélène to move to Langres in Haute-Marne, France, some one-hundred- eighty miles east of Paris. Hélène broke the news to Walter the night before she was to leave home. He was devastated and they had a tearful goodbye. Somehow, this would not be the end of this romance.

Grand’Mère Laure Quainon, Gaston’s mother, had been widowed twice before and her third husband’s name was Henri Leon Belime. Hélène was welcomed in Langres and immediately sought employment locally. Since Langres was not a big city, and the devastation caused by the war did not afford many opportunities for work, Hélène knew it would be difficult to find a job.

Walter had plans of his own. Whether it was pure luck or fate, there was an opening for an interpreter in the city of Langres which had just been liberated by the Allied forces on September 13, 1944. He arrived in Langres in early October. Hélène was unaware that he was stationed nearby.

She had secured a seamstress position in a small clothing store in the downtown area. One afternoon, as she worked in the store, she glanced out the store window and noticed several American soldiers walk by. Walter was one of them. She jumped up, ran outside on this brisk but sunny day in October, and called out his name. At first, he didn’t hear her, but after a second much louder yell, he turned to see who was calling him.

“Oh, my God,” he screamed. “I have found you.” He rushed to her side and they kissed for the first time in many months. A surge ran through both of them as they held each other tenderly in front of the store.

“When you told me your parents were sending you here, I immediately began to see how I could get here to see you again. And now that Langres has been liberated from the Germans, the Army needed some interpreters to understand the local people more.”

“You did this for me? You came here for me?”

“I love you, Hélène. I want to be with you. When are your days off?

We can meet here at your shop, or anywhere you want,” he said. “Tomorrow and Sunday, but on Sunday I must first go to Mass at

12 Ibid.

IN THE SHADOWS OF VIETNAM

11

the Catédrale Saint Mammès with my grandparents. We can meet after that. I can show you where everything is in Langres. It is a beautiful little town, and now that the Germans are no longer here, everyone is free to do what they want.”13

They

met on

Saturday

morning around nine o’clock, and she began to show Walter

Walter Salois and Hélène Podevin pose together for a photo taken in Langres, France in 1945. (Photo courte- sy of Fr. Phil Salois)

the sights as they walked together hand in hand. Walter noticed how

the city was surrounded by huge walls, as it was an ancient fortified city

overlooking lush greenery and open agricultural space that sprawled im- mediately outside the walls. She then took him along Promenade Jules Hervé where the scenery of the city and its ramparts were magnificent. She explained to Walter how Jules Rene Hervé was a French painter known for his depiction of Paris and the French countryside.

Langres, as she explained to Walter, was a military training area during World War I, so this was the second time the American military had over five-thousand men in the city at once. Their weekly sightsee- ing trips were always something to look forward to as their relationship turned to love. They were indeed in love, though the thought of the war ending meant Walter’s redeployment back to the States pending a new assignment and certain separation of the couple.

It was only a matter of time before her grandmother’s neighbors noticed Walter and Hélène together. They were spotted in a café one day. The neighbors, Madame Jobard et Madame Soubricas, told Grand’Mère Laure of their meeting.

“Laure, did you know that your granddaughter Hélène is seeing an American soldier?”

She did not, but immediately reported the incident to her mother in a telephone call.

“Henriette,” she said by telephone to Hélène’s mother, “Hélène is seeing an American soldier. My neighbors saw them together earlier

today.”

13 Ibid

12

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

“Maman, tell her you talked to me and that she must stop seeing

him or I will send her back here to Paris,”14 Henriette said.

When Hélène returned home later that afternoon, the grand-

mother informed her of what her mother had said.

“I’m not going to stop seeing him. I love him.”15

On very short order, Hélène’s parents brought her back to Paris,

assuming that if Walter was now in Langres, he couldn’t also be in Paris.

They hoped the separation would end the relationship, but Walter was not to be outsmarted, as within months he found a way to get retrans- ferred back to Paris. Once he arrived in Paris, however, he received word that he was being shipped home and likely would be redeployed to Japan, where the fighting was still intense.

Desperate and in love, he confronted Hélène’s father, Gaston, and asked if he would give him permission to marry her. The father agreed to the marriage, but Walter was sent back home to the states before the ceremony could take place.

When he arrived home in Woonsocket, he told his parents of his love for this French girl he had met and dated. He also pondered what to do. Before he had left for the war, Walter had begun a relationship with a woman named Noella (“Joan”) Salvas, a professional dancer and co-own- er of a dance studio with Walter’s cousin, Hilda L’Esperance, on Greene Street. He loved Hélène more than he did Joan, even though Joan hoped she and Walter would marry after he returned home from the war.

On May 8, 1945, World War II in Europe came to an end, and the war in the Pacific was nearing its end as well. Consequently, Walter was not reassigned to Japan as was originally planned. He picked up the tele- phone, got the long-distance operator on the line, and called Hélène in Paris.

“Hélène, the war is over. I don’t need to go to Japan either. I want to marry you. Come to the United States. I’ll send you the airfare and we can get married.”

“I love you too, Walter, but if you want to marry me, you’re going to have to come and get me,” she replied.

“Okay, I’m coming,”16 he answered without hesitation.

It took some time to make preparations for him to fly to Paris. They

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

IN THE SHADOWS OF VIETNAM

13

exchanged many phone calls during this time. Since Hélène and her family did not have enough money for a wedding gown, Walter agreed to have one made and to bring it with him on his flight to Paris.

The two were married in Notre Dame de Lourdes on Rue Pelleport in Paris on June 22, 1946. Henriette finally realized that this American soldier was different than many others, as he did come back to marry his true love.

The newlyweds flew back to Rhode Island and settled in the city of Woonsocket. Woonsocket was just one of the many municipalities whose economy was driven by the mill industry. The first mill in the United States was developed in 1793 when a twenty-five-year-old visionary by the name of Samuel Slater transformed the state from an agricultural-based society to an industrialized state almost overnight. With technology sto- len from his native England, Slater developed the nation’s first mill in the village of Pawtucket in the Town of North Providence, thereby igniting an industrial revolution. Nicknamed “Slater the Traitor” by British loy- alists, young Samuel ignited a spark that changed the course of history.

Soon, other wealthy Rhode Islanders opened similar style cotton mills in many other cities and towns throughout the state. In Walter’s native city of Woonsocket, these mills dotted the banks of the Blackstone River, an energy source used to power the mills.

Naturally, on several occasions over the next year, there were awk- ward moments when Cousin Hilda visited the family, and Joan tagged along. It took some time for Hilda and Joan to realize that Hélène was here to stay.

After two years of heavenly bliss, Walter and Hélène greeted the

arrival of their first-born, Philip Gaston Salois.

CHAPTER 3

Not Your Ordinary Childhood

“In a nine-month period,

Phil lost all three of his grandparents.”

The authors

Phil Salois was born on November 22, 1948 in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. His mother, Hélène, wanted to name him after one of the apos- tles, preferring not to name him Gaston after her own father. She said Americans would pronounce it wrong instead of using the correct French pronunciation. She also did not like the names Bartholomew, Matthew or Jude, and John was too common a name, so she settled on Philip Gas- ton Salois.

His father, Walter, had a strong Catholic faith, which he seemed to have passed on to his wife

Hélène who was not very de- vout of her own accord. In fact, before she met Walter, she, like so many people in France, were Catholic in name only. Many never practiced their religion, oth- er than going to Mass on

Sunday mornings.

Following World War II, the population of Woonsock- et began to grow at a rapid

Undated photograph of the Lafayette Worsted Mill in Woonsocket, RI, the mill in which Walter Salois worked for many years until it was completely destroyed by fire as a result of Hurricane Diane in August 1955. (Internet photo)

16

Julien Ayotte and Paul F. Caranci

rate. The textile industry was still booming in the state, and mills were still cropping up in many cities as fast as they could be built. Walter had a background in accounting and was able to secure employment at the La- fayette Worsted Mill, while Hélène worked as a seamstress at Finkelstein’s Factory on Singleton Street. Walter’s mother, Eva, did not work, though his father worked at the U.S. Rubber Shop. The rubber shop was instru- mental in making rubber tanks to be used as decoys during World War

II. The work was strenuous, but it allowed the family to live comfortably and build a future for themselves.

In August 1948, Hélène, in her sixth month of pregnancy, received word that her father Gaston had died. She flew to Paris, without ac- companiment, to bury her father. Phil was born three months later in November, and just three months after his birth Hélène realized that it would not be feasible for her widowed mother to live by herself in Paris. She convinced her husband Walter that Henriette should live with them on Angel Street in Woonsocket. So, baby Philip’s grandmother became his nanny until her death on May 2, 1966. Interestingly, Henriette, in all her years living in the United States, never became a naturalized citizen and never learned to speak English.

In 1956, when Phil was eight-years-old, he suffered from a severe case of bronchial asthma. On October 6th of that same year, his father also found himself out of work when the Lafayette Worsted Mill was destroyed by fire and burnt to the ground. The owners had neither the money, nor enough insurance coverage, to rebuild the mill, and Walter lost his job. During this time, both power and labor costs had climbed significantly, attributable in part to the formation of the textile union that had orga- nized years earlier to boost mill workers’ wages. Lower labor costs in the South were more appealing, and many mills had already closed by 1956. One can only wonder if the destruction of the Lafayette Mill by fire elim- inated the inevitable layoffs that were likely to follow anyway.

Phil’s doctor had informed his parents that Phil’s condition would greatly improve if they moved to a warmer and less humid climate which would be healthier for his asthma. So, Walter decided to leave for California to find both work and a new home. It was in those days that the axiom was heard over and over again, “Go West, Young Man,” because it was the land of opportunity. It took him nearly a year to secure a job there and to find affordable and suitable housing for the family before he returned to Woonsocket to prepare for their move out West.

Eventually, Walter was offered and accepted an accounting position with